8

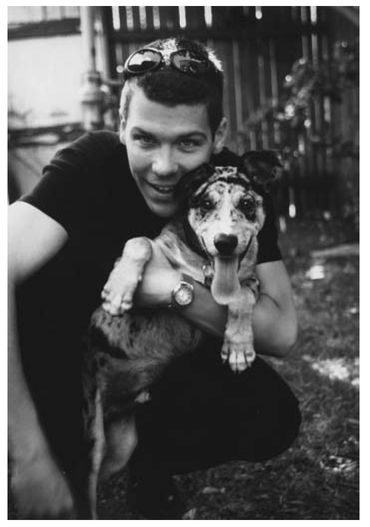

Bonding with Non-dogs

In this chapter we’ll look at the unique relationship that has grown from fundamental similarities between dogs and humans when it comes to mental processing and behavior. Domestic dogs seem to understand human communication more than any other species and so have adapted to our social circumstances.

It is something like a lottery for each dog entering a new home. As the great opportunists, they need to find a human who can help them access opportunities; in other words, they need to be guided to learn the behaviors that will get them the resources. Those dogs that exemplify their breed standard will be chosen by humans who excel in showing them, and these dogs will get the chance to reproduce; the rest of the dog population need life-coaches who excel at getting the most out of Canis familiaris as companions. The dogs that score the best life-coaches have the best lives. And those of us who love our dogs want to see them enjoy life to the full; we want to be their best life-coaches.

The role of the human-dog bond

The cement of human-dog bonds is often called trust. This term frequently crops up in books about animals and their training, but what does trust actually mean to Feral Cheryl? How does it define the quality of her relationships with fellow pack members? Your dog trusts that you will scratch his chest when your hand goes towards him; he trusts that you will have food in his bowl when you lower it to the ground; and he trusts that you will throw the ball when you have a ball in your hand. At the same time, he trusts that you will not hit him, offer him an empty bowl or do a dummy throw. Why? Because you usually do scratch him, fill the bowl and throw the ball. Trust is built entirely on consistency.

In training you strike a deal with your dog. Applying a humane set of rules when simply being with your dog rather than when formally training him, maximizes the consistency, which establishes trust, which establishes a bond. This is why bonding can affect how dogs appear to obey rules. Dogs bonded to their owners often wait for permission to begin an activity, while dogs who have not bonded do not. For example, if you compare a true companion dog with an outdoor guard dog, you’ll see that a guard dog that lives apart from its owner is virtually autonomous compared with the bonded house dog. The guard dog has no regard for triggers, cues and commands from its owner because he has not spent enough time with him to learn the relevance of that human as a source of opportunities—as a useful coach.

There is clearly a link between bonds and being an effective coach. Verbal praise from a human with whom a dog has no bond is irrelevant to the dog. Most vets recognize that telling a dog during an examination that it is a “Good boy!” is as useless as reading out a shopping list and that they are far better off giving their patients dried liver or a chest scratch. The “Good boy!” has to be learned as a secondary reinforcer for it to be valued, and the human issuing it has to be bonded with the dog receiving it.

Unfamiliar humans may offer worthless praise, but familiar humans can be equally untrustworthy. Owners who tease their dogs often wrongly imagine that their dogs always get the joke. Of course, such ill-advised owners are supremely inconsistent in that, at least some of the time, they have to honor the beneficial deals they have struck with their dogs. If they teased their dogs all the time, the dogs would avoid them or bite them. It is worth considering why some owners are inconsistent, often inadvertently. Some want to show off to their mates or partners. Some are just plain mean. Others attribute too much cognitive power to their dogs and assume that the dogs always know they are only kidding. In canine language the only way a dog can know that a joke is coming up is for the owner to perform a play-bow. This intriguing signal tells the dog that the behaviors that follow are playful or at least not to be taken seriously. Its critical importance is in preventing boisterous playful overtures being misread and precipitating fights. Importantly, owners should appreciate that their own play-bow signal should be used consistently as a warning of chase games, stalking and staring, and even rough play.

Dogs love social contact

Dogs have a deep need for contact with a social group. They can detect emotional shifts in their human fellows and will, for example, gaze at them longer when they are watching cheerful movies than when watching sad movies. Social contact is probably the most defining feature of dog behavior. This is hardly a bold claim, but if you don’t believe me, consider the following story. I was studying horse behavior a couple of years ago in the Australian bush. I was directed to a herd of brumbies (Australian feral horses) in a state forest one hour’s drive off surfaced roads and 45 minutes from the nearest house. I set off with an old friend, and we encountered the herd just where the state park ranger had predicted. We were soon crawling towards them to gather data. To our amazement, we spotted a dog with the horses, a lithe black kelpie cross that was as surprised as we were by the encounter. Far from wanting our company, he nimbly hopped over a fallen tree and fled, forsaking the horses. Given the distance from human activity, we assumed that he, too, was feral and that he returned to the company of the horses when we had gone back to the field station.

It is fascinating to speculate why the dog had bonded with the horses. Maybe he kept close to the herd to scavenge on foal feces (which, being derived from milk, can be nutritious for dogs) or possibly even afterbirth. Another particularly tantalizing possibility is that he relied on the surveillance provided by so many pairs of eyes. Indeed, the horses were the first to spot us as we advanced slowly toward them. Intriguingly, he seemed to respond to the horses’ gaze when they spotted us, and only then did he seem to see us and flee, notably well before the horses moved away from us. The likely benefit for this dog of being in a social group seems to have been protection. Unlike regular dogs, he may have had a good reason to enjoy this situation—specifically that he would not have had to share resources with the other members of his group, which, had they been dogs, would have been competitors.

Over-bonding and the risk of separation anxiety

Psychologists speak of attachment and detachment, terms developed chiefly to describe bonds between human infants and their caregivers. The bonds that tie us are dubbed “attachment relationships” by psychologists, a term first used to describe the bond between children and their mothers. Under normal conditions, the process of attachment binds pups to their dams, while detachment effectively severs that maternal-infant bond and makes way for socialization with others. It’s thought that an attachment bond between a dog and its human caregiver (the so-called attachment figure) can be artificially created when the human responds to all the dog’s attention-seeking demands in a way that its dam never would. One theory is that such a strong bond can lead to dysfunctional hyper-attachment. This over-bonding becomes evident if the dog gets distressed when kept apart from its attachment figure.

The belief that owners can over-bond with their dogs is certainly controversial, mainly because it’s a philosophy that can drive an unnecessary wedge between dogs and owners who would otherwise form a completely healthy bond. In fact, according to some studies, dog-related factors were more likely to cause separation-related distress than elements of the owners’ behavior. For example, one study showed that dogs whose owners interacted with them anthropomorphically (ascribing human attributes to animals), did not engage in obedience training, and “spoiled” them in certain ways were no more likely to develop unwelcome behaviors than those given more discipline.

CHEW ON THIS

According to a recent study, dogs living with a single adult human were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have separation-related distress than dogs living with two or more people. Low numbers of humans seemed to increase their individual value. The same study showed that neutered dogs were three times more likely to have separation-related distress than entire dogs. With a great increase in the number of dogs living with just one person and the rising (and laudable) tendency for owners to neuter their dogs, it’s not surprising that separation-related distress is becoming an enormous problem.

When inappropriate bonds form, owning a dog may become too difficult, or dogs may simply struggle to meet their owners’ expectations. The prevalence of separation-related distress is a worry to the pet industry as it tries to encourage more people to own dogs in the face of a worldwide decline in ownership. Few owners seem put off by the potential costs of looking after the physical health of their dogs. If they did, they’d do more prepurchase research to find a puppy that was free from inherited diseases. But if such veterinary costs aren’t a deterrent to owning a dog, what is? Well, it seems that many people are put off dog ownership by certain behaviors that they regard as unacceptable.

Perhaps we expect too much from dogs. We expect them to know that we are going to return when we leave them alone, and we expect them to have the social decorum of an acceptable human member of society. The veterinary profession has a vested interest in equipping the public, especially dog owners, with skills that help them to understand how dogs behave and to minimize the most unwelcome—but normal—responses.

Separation-related distress is a good example of how humans can be insensitive to the needs of companion dogs. Indeed, many people laugh at the suggestion that dogs could be prone to such a diagnosis. (They assume it arises when over-pampered pets encounter under-worked vets.) One study in the United Kingdom showed that while 50 percent of dogs had some signs of separation-related distress, fewer than 3 percent were presented to vets for treatment. This may reflect the fact that, although it is the most common cause of complaints to local councils, many owners don’t recognize barking as a problem because it mostly happens when they are somewhere else. Further, the study indicates that few owners think of vets as effective physicians when the mind of their dog, rather than the body, is diseased.

Better matching of dogs with owners and their lifestyles may avoid inappropriate bonding, but it’s difficult to see how the same dog can be reliably affectionate and yet unmoved when the object of its affection departs. Perhaps the solution is to train dogs to be left alone and even to enjoy their solitude. Separation-related distress is so common that rather than simply expect it, we should develop preventive strategies that reduce the impact of separation from key attachment figures. These include protocols that allow owners to bond with their new pup without over-bonding (for example, the use of an indoor kennel to allow the human to give the dog time and proximity on his terms rather than the dog’s). The same approach may be useful for freshly rescued pound dogs, a group known to be at high risk of separation-related distress. The problem is so important that the pet industry should support research to identify management practices in breeding kennels that may reduce the risk of litters developing separation-related distress.

CHEW ON THIS

A recent study of cortisol concentrations (the stress response) in kenneled dogs has shown that levels do not peak until the 17th day of kenneling. The parallels between rescue shelters and boarding kennels are more obvious to dogs than they are to humans: no familiar pack, lots of unfamiliar humans and lots of unfamiliar dogs, mostly barking. This means that we should expect our dogs to be very emotional after only a two-week period in a boarding facility. Essentially, their stress response is likely to be still developing at that stage.

Some bonds are established early

A pup’s early experience has a critical effect on its behavior later in life. Innate signaling systems play an especially important role in a pup’s early experience, as underlined by recent reports of the effects of Dog Appeasing Pheromone (DAP). Derived from the waxes secreted by skin surrounding a bitch’s udder, DAP calms some distressed dogs. As such, it holds promise in the treatment of separation-related distress and noise phobia and is being marketed as a plug-in diffuser. This is particularly helpful because it bypasses the need for even the simplest form of learning—habituation. The owner does not even have to be present for DAP to work. The appeal of such innovations is that we simply cannot make mistakes with it, and it requires minimal effort. This is an exciting possibility, but we should bear in mind that there is no such thing as a quick fix and that any intervention must incorporate ongoing behavior modification. The best dog owners appreciate the subtleties of learning theory even if they do not recognize them as such.

Dogs make us feel safe

An improved sense of security is part of why we own dogs. After getting a dog, many people report that their fear of crime has been reduced. Similarly, owners of hearing dogs report that the dogs fulfilled their main expectation of alerting them to sounds but also made them feel safer.

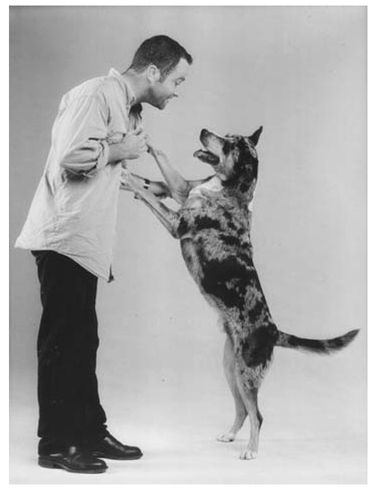

Encountering new faces

Within seconds of meeting a new face, dogs decide whether they like or dislike it. They work out which party is more likely to be able to move away without seeking permission from the other, and that is virtually that. Admittedly, the arrival of a third party can swing the balance of power, and there may be future disputes over certain resources, but the status within the pair is usually worked out very quickly. By the same token, dogs seem to work out within an instant or two whether they are always going to be on edge with certain individuals: the rules of getting to know another dog apply to other species. Every first meeting, be it with a dog, horse, cat or a human, tends to influence the success of subsequent encounters with that species. So, if the first meeting is critical for harmony, at least two questions must follow: Should we worry about our body language when we meet dogs for the first time? Yes, by avoiding staring and standing over a dog, we can invite it to approach and assess us. If things have gone badly, can they ever be set right? Definitely. Habituation and delivering rewards are critical avenues for success with cautious dogs. They are discussed in the next three chapters.

CHEW ON THIS

With some notable exceptions, much of the legacy of Uncle Wolf survives in the behavior of his descendants. The elements of a hunt have been channeled into the various breeds that cater to man’s need for canine specialists alongside him when seeking and capturing prey. It’s useful to consider the roles that each member of a wolf pack may have taken during a hunt. One can imagine some members of the group being in charge of visual surveillance (the movement monitors) while others were tuned in to changing smells (the scent sniffers). The movement monitors would alert the group to possible prey on the move, especially in their peripheral vision. But cooperative hunting depends on a fine balance of skills within the team: a blend of prey detection (sniffing and spotting) and prehension (grabbing and killing). So, for a team to be effective, the enthusiasm of the visually sensitive pack members had to be supplemented by other types of players. The scent sniffers and the generalists in the pack would have learned to ignore many of the movement monitors’ false alarms.

Small children are especially challenging to dog owners who want to keep dogs calm and kids safe. Preverbal children are especially tricky and, through no fault of their own, often do all the wrong things. They scream, run, pick up toys and, oh so often, are smeared with traces of chocolate. All of these make them irresistible to playful young dogs, particularly working breeds such as collies. The inclusion of those amazing border collies in the Babe movies proved disastrous for the breed because children demanded dogs like the gentle, patient, charming “Fly” from the farmyard flick. Beautiful border collies that should have been on farms working found themselves in urban homes and did what came naturally: they chased . . . anything. In this instance, anything could include children’s toys, the little hands that threw those toys, and ultimately the children themselves. And so it was that border collies were surrendered to pounds in droves (in numbers that were matched only by Saint Bernards after the movie Beethoven, Neapolitan mastiffs after Turner & Hooch and Dalmatians after 101 Dalmatians).

Language barriers

We smile, but dogs bare their teeth; dogs pin their ears back when they are fearful, but ours are pinned back permanently; dogs have tails, but we do not. These and other anatomical differences make it rather difficult for us to mimic canine signaling with much subtlety. Humans who fall into the trap of assuming that they can speak the language of dogs may fail to recognize the negative effects of some of their behavior and so put dogs under inappropriate pressure. If our body language means anything to dogs, it’s either because it approximates something other dogs do or because it’s associated with things that other humans have done before. One could spend a great deal of time practicing yawning, lip-licking, displays of deference, and so on, only to use such skills on a dog that has learned to ignore humans because their signals do not compute and are, therefore, virtually irrelevant.

Making oneself attractive to dogs can be a thankless task. You might have seen people trying to befriend an unfamiliar dog, often with a great deal of bending, stooping and crouching, cooing, billing and whining—all with an open mouth and enthusiastic but unnecessary head-nodding, often to no avail. Most dog people know that for every dog that relishes the opportunity to get close and personal with a stranger, there are ten that just walk on by. It is unlikely that we are ever mistaken for other dogs, so we shouldn’t expect to be of great interest to dog-focused creatures. We do not walk on four legs and therefore do not match up with the visual signals that tell a dog it may be dealing with another dog. Besides which, we do not smell like other dogs. Even if we have been in the company of sexually mature and intact (entire, not neutered) dogs, we rarely give out enough borrowed odor to prompt either aggression or courtship. Vets are among a small group of people who regularly work with a transient number of dogs and are therefore exposed to the odors of various possible canine contenders. But they are certainly not considered high risk for sexual overtures or male- male aggression. This is evidence enough to debunk the notion that dogs smell us as if we were dogs. Added to this, one has to accept that while crotch-sniffing of humans is a regular doggy greeting and always occurs at the most inopportune moments, bottom-sniffing—a far more common dog-dog activity—is thankfully rare in dog- human interaction!

Dogs are ever optimistic and resourceful

Dogs have short lives, and they seem to value our company very highly, yet often and repeatedly we have to leave them alone for extended periods. We can’t really know what their fears are in this situation. The good news is that dogs rarely pine forever. Even if they weep and wail when we first leave, they remain resourceful opportunists. They will happily depart with a new guardian if sufficient enticement is on offer. Grayfriars Bobby, the legendary Edinburgh dog who never left his owner’s grave, may be a notable exception, but then again he may have been accidentally trained to stay put by the generosity of those who brought food to him.

Aggression to humans

While separation-related problems are usually top of the list among clients seeking behavioral advice from vets, aggression towards family members sometimes eclipses it. Dogs regularly bite to defend themselves, and veterinarians are among the chief victims. However, dogs most commonly bite when defending their resources. Often the humans around them don’t recognize the value dogs place on certain things, which makes it hard to avoid trouble. An obvious example is giving a dog a bone to chew when a toddler is around. More obscure resources include companions and territories (and among the most valued I would include the park that is most often visited and marked).

But despite the undoubted importance of human behavior in dog-bite statistics, there are few strategies in place to prevent dogs with such tendencies being bred in the first place, even though these animals are becoming increasingly unacceptable. Indeed, on the contrary, it has been suggested that qualities such as showmanship, presence and attitude, which are valued in the show ring, may translate on a day-to-day basis into status-seeking, predisposing dogs to fight with other dogs or even defend their resources from humans.

Aggression can be innate or acquired. Breeding for suitable temperament can certainly reduce the prevalence of aggression in dogs. Domestication itself provides ample evidence of this, if any were needed. Dogs that turn on their breeders are routinely culled. However, while we await breeding strategies to create the very best companion dog temperaments, we must acknowledge that the role of learning is also critical. A dog learns to bite if that gets rid of the human hand threatening him. In this case, hand-related threats can include the hand that drags the dog from the sofa, the hand that grooms tangled fur (especially on the tail and hindquarters), the hand that pets in taboo areas (over the nape of the neck of a dog with unchallenged status), and the hand that takes food away. If you’ve ever removed your hand from a growling, snapping or biting dog—and why wouldn’t you?—you have trained it to growl, snap and bite louder, quicker and harder in future. Further, hitting a dog for doing these things is never a good idea because it signals to the dog that combat has commenced. We should train dogs from a very early age to behave appropriately when they have to deal with unavoidable flashpoints, such as going to the vet. This approach is particularly useful for high-risk dogs, such as those bred to use their teeth, as the fighting and herding breeds.

Predictors of aggression reported in recent studies included a few surprises. For example, in one report, female dogs were high risk, particularly small breeds and if neutered. The type of human predisposed to owning a dog that bites has yet to be fully studied. Having said that, a study of aggression in English cocker spaniels showed that owners of less aggressive dogs tended to be older (65+ years) and more attached to their pets. This study also showed that factors thought to cause status-related aggression—such as feeding the dog before the owner eats, a lack of obedience training, and playing competitive games with the dog—did not in fact do so. This is but a tantalizing glimpse into the unfathomed side of the dog and owner pair. We need to consider the role humans play in the emergence of aggression, and indeed all unwelcome behaviors, in dogs.

Being a life-coach rather than a leader

The role of humans in the life of dogs can create confusion or, worse still, conflict with dogs. This is why behaviorists try to provide models explaining how a dog may view its human companions. But the quest for a one-size-fits-all template presents problems. Does the role of leaders in groups of dogs change with context? If so, can we really expect to be leaders to our dogs under all circumstances? Or should we instead accept that the communication between a dog and its canine leader cannot be achieved between dog and human? Again, I’m all for the concept of a coach who helps the dog to exploit the environmental niche of the family home as successfully and agreeably as possible.

Imposing physical pressure or discomfort and so-called dominance over a dog may be seen as applying and withdrawing aversive stimuli and therefore considered a legitimate training method. But as we saw in chapter 5, there is growing distaste for the term “alpha,” since this implies domination and permanency. In dog-training circles, this trend has given way to the notion of leadership. But the concept of humans as leaders of dogs brings its own set of problems. It implies that all dogs that “respect” a human as leader and have bonded to him or her will follow that human even when other dogs are around, getting to know each other, sniffing bums and playing. The truth, of course, is that this is more a matter of training and coaching than of a unique dog-human understanding.

Naturally reared dogs (i.e., pups that remain with their mother) will always find those of the same species more relevant than humans as leaders. Perhaps we should simply accept that we are, at best, caregivers and companions, and when we are not giving them care and companionship, we are coaching them. Although there is clearly some overlap between caregiving, companionship and training, there seems to be sense in compartmentalizing them. To do so helps us approach each set of activities with clear expectations.

Some people reckon that just as motivation changes with context, so, too, does the eventual winner in any contest over a resource. Let’s draw a human analogy: The leader we might select for a trip to the South Pole or to represent us at a professional gathering would be different from one who might lead us to the best bar or club. What we are being asked to do is to nominate the person who gives us the best deal for survival, representation or enjoyment. I’m not convinced that the analogy works, because we have better understanding than a pack of dogs about the specific challenges and resources of these missions.

There’s little evidence to suggest that dogs can make such predictions. Their values seem less fluid than ours. Admittedly, they enjoy fun, but what are the games they play: possession, chasing and killing, and retrieving? Recalling as they do elements of the pack hunt, these are essentially activities that determine survival. Of the three human alternatives, the trip to the South Pole is the best example of how we might select leaders if we were dogs. We would want clear direction from someone who was consistent and impressive. It would also help if the leader was inspiring, and it would be especially good to know that the leader was innately benign.

How do we behave like a leader? We initiate missions, play, feed and groom, and usually dictate the path taken by the group . . . but not always. In many ways we behave like a most unimpressive leader. We may lag behind on a walk and show no interest in the stimuli a walk offers to a dog. How many humans sniff trees and lampposts let alone mark them? Wouldn’t a leader do so? Yet we leave that to other members of the pack. So here again, the notion of owners as life-coaches seems to have more universal merit than that of a leader.

Life on the leash

Heelwork is fundamental to obedience training and can prove invaluable when you want to steer a dog out of trouble and have no leash handy, but being on the leash or walking to heel are not normal situations for a dog. Consider for a moment what this is like for a dog. Being on the leash means:

• permanently invading the personal space of a group member (the human holding the leash)

• risking being trodden on by shod, and therefore potentially pain-causing, feet

• being scarcely able to see the human at the end of the leash, since he or she is facing ahead and busily dodging lampposts.

Dogs do not see the same things as humans. For a start their eyes have different optics that lead to different magnification and visual fields, factors that are compounded by the fact that dogs’ eyes are far closer to the ground than are those of the shortest human. Consider for a moment then the plight of a diminutive breed, such as a Yorkshire terrier, as it navigates along a busy footpath. It is, in essence, in a forest of feet and ankles that move about, up, down, forwards and backwards, without much of a predictable pattern. An added challenge for the little dog is that the leash may cause some degree of neck pain unless he can truly predict every last step the owner may take and so avoid any correction/guidance. With these two possibilities, it’s not surprising that so many of these dogs are able to persuade their owners to carry them.

Assuming that the handler follows the convention of keeping the dog to the left, most dogs on leashes are confined to one side of the human, even though intriguing things may be on either side, and town planners never seem to have the sense to put trees on both.

CHEW ON THIS

The long-standing convention that dogs must be led on the left of the handler has its origins partly in the formality of military drill, which demanded that service dogs looked neat and tidy while being put through their paces (in the same way that the sitting trot was adopted by military riding schools to avoid the uncoordinated bobbing and dipping of cavalrymen’s heads). But it also harks back to the bad old days when choke chains were accepted as the normal connection between a dog and its human.

A note here for those people who still insist on using choke chains: You must be aware that your dog can never safely cross from one side of you to the other. In doing so, the dog turns the sliding noose in the chain from a quick-release mechanism to a potentially deadly ratchet. Since the unenlightened are the greatest fans of choke chains, the chance of this message being accepted by all choke chain users is bleak. The only option seems to be to ban the hideous things.

Does the convention of leading dogs on the left-hand side have any repercussions for dogs? Some handlers may be following a convention that compromises their handling ability. For example, some humans may be more dextrous with the right hand, while the left is traditionally used for correction and negative reinforcement. So some dogs may be at a disadvantage purely because their handlers are strongly right-handed. Maybe certain dogs cope with the constraints of being on the leash (including neck pain, if choke chains are used) better than others because they are innately left-handed or right-handed. If the left eye is dominant, then they may be more likely to be distracted by visual stimuli, since there is more to see on the left where the handler’s leg does not get in the way. This is considered further in chapter 14 on individual differences.

Harnesses are becoming more popular, especially those that direct the head. An abundance of such head collars is now available, each with its claims to superiority. The intrinsic cost of such devices is almost negligible—after all, we are only talking about a couple of strips of nylon webbing and the occasional metal loop and plastic fastener. In fitting head collars correctly (preferably a job for an experienced vet or behaviorist), the critical questions are whether the webbing will get too near the eyes (if it is safe) and does the collar stay put (if it works).

Other forms of harness are designed for the chest. They can be very useful for dogs that have breathing difficulties or delicate windpipes, such as Yorkshire terriers, which tend to have collapsible tracheas. Dogs that pull on the leash are not necessarily good candidates for these chest harnesses, because harnesses encourage pulling, as in the case of sled dogs. Surprisingly, a harness is thought to be useful in body-building and making a dog stronger. The more muscular breeds, including Staffordshire bull terriers, have attracted an unhelpful fan-base in a sector of the human community with a high tattoo-to-teeth ratio. Here the belief is that harnesses, with clips that allow an increasing number of weights to be carried, will give the dog a workout and beef it up in the process. The evidence for this having any strengthening or even cosmetic effect is slim, but the spirit of machismo that promotes this sort of behavior is alive and well. One wonders what other malpractices from human gymnasia are being perpetrated on these poor animals.

Pet dog trainers and behaviorists often recognize a suite of behaviors associated with the leash. Some call these responses leash frustration. A dog with leash frustration changes its behavior for the worse whenever restrained by the collar and leash. Many are aggressive to other dogs but only when on the leash. Many have acquired this response from being reefed to heel by anxious owners. Dogs with leash frustration often pull on the leash, which means that the owner is pleased to be able to get them off the leash, so they get the dog to an off-leash park as soon as possible. The dog’s job is thus to pull them to the point of leash release as quickly as possible . . . and then avoid being recaptured.

CHOICE CUTS

Domestic dogs seem to understand human behavior better than any other species.

Trust is built entirely on consistency.

Dogs bonded to their owners respond to cues; dogs that have not bonded behave autonomously.

Dogs are supremely social animals.

Having unrealistic expectations of dogs can put some people off dog ownership.

Many dog owners don’t appreciate the seriousness of separation-related distress.

Anatomical differences mean that humans can’t understand dog language.

Instead of leadership and dominance, we should aim to be caregivers and companions to our dogs.

Time spent training a dog to walk to heel is time very well spent.

Dogs do not cuddle one another. During the socialization period, dogs learn that many of the ways in which we interact with them are not to be feared.

For some dogs, eye contact with humans can be reinforcing and thus can perpetuate boisterousness, contrary to the owner’s wishes. For other dogs, direct eye contact can be challenging and can provoke defensive aggression.

Domestic dogs seem to understand human behavior better than any other species.

Domestic dogs seem to understand human behavior better than any other species.

Trust is built entirely on consistency.

Trust is built entirely on consistency.

Dogs bonded to their owners respond to cues; dogs that have not bonded behave autonomously.

Dogs bonded to their owners respond to cues; dogs that have not bonded behave autonomously.

Dogs are supremely social animals.

Dogs are supremely social animals.

Having unrealistic expectations of dogs can put some people off dog ownership.

Having unrealistic expectations of dogs can put some people off dog ownership.

Many dog owners don’t appreciate the seriousness of separation-related distress.

Many dog owners don’t appreciate the seriousness of separation-related distress.

Anatomical differences mean that humans can’t understand dog language.

Anatomical differences mean that humans can’t understand dog language.

Instead of leadership and dominance, we should aim to be caregivers and companions to our dogs.

Instead of leadership and dominance, we should aim to be caregivers and companions to our dogs.

Time spent training a dog to walk to heel is time very well spent.

Time spent training a dog to walk to heel is time very well spent.