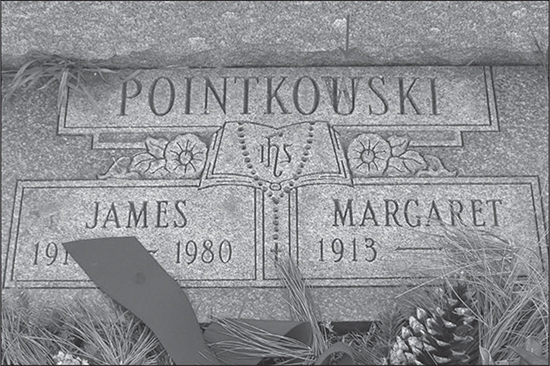

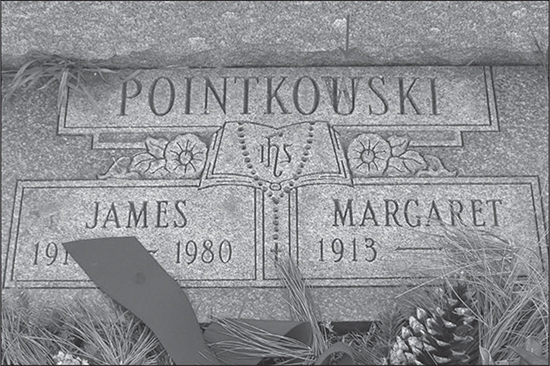

Even James Pointkouski’s tombstone has a variant surname spelling: The carver goofed by substituting a w for the u, then corrected the mistake on the stone.

This book has presented a variety of sources and strategies you can use to uncover answers about your Polish, Czech, or Slovak ancestry. Of course, each of your ancestors experienced unique life circumstances that affect the research path you’ll follow—you can’t count on any one record or research technique to provide answers every time. The process for each family and ancestor will be a bit different. To illustrate this point, this chapter contains three examples of successful Eastern European genealogy research—one Polish, one Czech, and one Slovak—to show you how real-life genealogists have overcome the types of roadblocks you’ll encounter.

Avid genealogist Donna Pointkouski of Palmyra, New Jersey, has traced her family roots back to Poland’s Mazowsze and Wielkopolski provinces since beginning her research in 1989. In this case study, adapted from a post titled “How Do You Spell That?” on her What’s Past Is Prologue blog <pastprologue.wordpress.com>, Pointkouski recounts the perils of having a perplexing Polish surname.

* * *

Even James Pointkouski’s tombstone has a variant surname spelling: The carver goofed by substituting a w for the u, then corrected the mistake on the stone.

I ALMOST FELT SORRY FOR THE TELEMARKETERS calling my parents when I was young. I’d answer the phone and hear, “Hi, can I speak to Mr. … uh, Mr. Po-, er, ah, Mr. P-p-pint, er, Mr. Portkonski?” I’d pause for dramatic effect, then respond, “No, I’m sorry, there is no one here by that name.”

But worse than the telemarketers was the need to spell my name—all the time. Even my parents talked about changing our surname for a while. We considered my mother’s equally Polish maiden name, Pater, because it seemed easier. For a while, Perry was in contention just because we liked it. Until my father called in a pizza order and the clerk asked, “What’s the name?” My dad grinned and responded, “Perry!” But then the clerk asked, “How do you spell that?”

By now you might wonder why we feel no allegiance to our moniker. The answer is simple: It’s not our true name. My grandfather James made it up. If he had invented a name that was easier to spell and pronounce, I’d thank him. As I delved into the family’s history and gained pride in my Polish heritage, I was disappointed I couldn’t have the “real” name that he changed slightly. Unfortunately, the nonlegal change was made just prior to all of today’s rules, records, and federal regulations, and now I am one of only eight people on earth born a Pointkouski.

James’ parents were Jan Piątkowski and Rozalia Kizeweter. Jan was a leather worker, and the family lived in Warsaw. Jan was born in Warsaw, and Rozalia’s family moved there from just outside the city when she was a girl. They had a son, Józef, born in November 1903, and a daughter, Janina, born in December 1905. Shortly after Janina’s birth, the family decided to leave one big city for another. Jan immigrated to Philadelphia in March 1906 with his sister’s husband, Ludwik Czarkowski. Rozalia and the children followed in November. In America, their first names were Anglicized to John, Rose, Joseph, and Jean. But the last name changed slightly, too. In English, the Polish letter ą does not exist—so Piątkowski became Piontkowski.

That’s the name my grandfather, my father, my brother and I should all bear. But the name change game continued with my grandfather.

James was the surprise baby, born in Philadelphia on July 6, 1910. His father was thirty-nine years old and his mother was forty-four, old by 1910 standards. On James’ official Pennsylvania birth certificate, the name is listed as Ganus Kincoski. I assume Ganus is what became of James when spoken with a heavy Polish accent. Kincoski was apparently an alias my great-grandfather used, temporarily, attempting to hide from either law enforcement or people he owed money. Other than around 1910, John always used Piontkowski, his correct surname, on legal records.

By the time James, or “Jimmy,” reached adulthood, he tweaked his surname further. As early as 1933, James changed a few letters and—voilà!—the surname Pointkouski was unofficially and unceremoniously born.

James’ older brother, Joe, changed his name, too (also not legally). I always thought Joe had more sense, though, for the name he chose was a lot easier to spell: Perk. Ironically, I recently got to speak to one of Joe’s daughters, who complained of being teased in school and called “Percolator”—to which she yelled back at her bully, “My real name is Pointkouski!”

My grandfather apparently tried this name for a while: He refers to himself as Perk in a letter to my grandmother in 1933, and a photograph of my father in 1936 is labeled Jimmy Perk on the back. But on all legal documents, my grandfather continued to use Pointkouski.

I remember my grandfather from my childhood, but I didn’t see him very often. I wish I knew him better, and longer, because he passed away before I could ever think to ask him why our name is spelled the way it is. James died on February 13, 1980, at the age of sixty-nine.

In what I refer to as “The Final Misspelling,” the monument maker accidentally carved a w into James’ tombstone and corrected it to a u. A larger, correctly spelled stone is also in place.

Gradually, despite wishing I got to use my real Polish name Piątkowski (as a female, my name in Poland would be Piątkowska), this English major has embraced the permanent misspelling and is proud to be a Pointkouski—even if you can’t spell it.

Lee James of Olympia, Washington, shares the following case study detailing how he traced his Czech immigrant ancestors. James, a retired research engineer of forty years, has redirected his research to genealogy. The story is adapted from “The Emigration Sage of the Family of Tomáš Kohout,” an article originally published in the December 2010 issue of the Czechoslovak Genealogical Society International’s journal, Naše Rodina (Our Family).

* * *

MY MATERNAL GREAT-GRANDFATHER TOMÁŠ KOHOUT was a podruh (a landless peasant farmhand) who lived in the southern Bohemian village of Hamr, about four miles south-southeast of Veselí nad Lužnicí in the Tábor region. Tomáš was born on November 1, 1837, in nearby Višný (modern spelling: Vyšné) to a woodcarver and his wife. In 1867, he married Marie Kalát (or Kalátová), a woman ten years his junior.

As a landless peasant, Tomáš Kohout had a bleak future in the Bohemia of the 1860s and 1870s. Because Bohemian families often had many children, not every son could inherit land from his parents, making property scarce and expensive. Coupled with a partial crop failure and other factors, this caused consumer prices to rise, making it harder for farmers to make ends meet. So when Tomáš’ father-in-law, Vojtěch Kalát, a domkář (a householder or “cottager”) who owned house No. 10 and an adjoining field, sold his house to his son in 1873, any chance of land ownership (and thus economic prosperity) for Tomáš ended.

Further, the Austrian Empire—which controlled Bohemia—was engaged in a two-front war against Prussia and Italy in 1866. Tomáš served in the Austrian army on the Italian front. Although a final peace treaty was signed, the victorious Prussians kept occupation forces in Bohemia long enough to visit every community and demand their pro-rata share of war reparations. A war veteran like Tomáš might not have been treated well by the occupying Prussians.

Such postwar troubles probably factored into many Bohemians’ immigration to America in the coming years. Clearly, Tomáš and Marie were seeking a better life in America when they decided to emigrate.

Austria’s government, which considered its inhabitants (especially the working segment) part of the national wealth, opposed emigration—as did the Czech bourgeoisie, which feared rising Germanization of the Czech populace, and the Catholic Church, which worried that emigrants would lose their Catholic belief in the new country. Consequently, Austria placed legal obstacles upon emigration. The Kohout family had to meet several conditions before they could legally move to America, including meeting military commitments. According to his discharge papers, Tomáš served ten years, two months, and eighteen days in the Austrian Army, most of which was served in the Reserves with one month of active service in the War of 1866. Hence, he had fulfilled his military requirement for emigration. It was also necessary for him to be a Catholic in good standing, be law abiding, owe no debts or taxes, and demonstrate that he had sufficient funds to get to America.

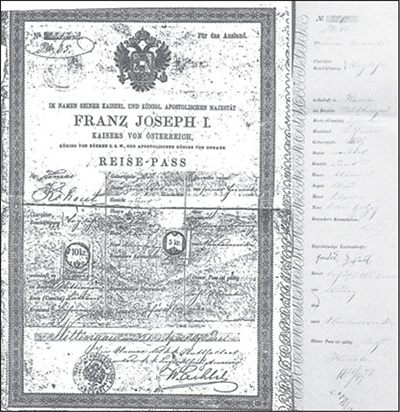

The preparation of an application for emigration permit indicates that Tomáš met the government’s requirements. I’m lucky to have two pages of Tomáš’ file from the Jindřichův Hradec district archives—in general, the Czech archives did not consider application for emigration permits to be of permanent value, and most of them were lost, misplaced, stolen, or burned for heat during the communist era. Tomáš’ file was found in an unmarked, unindexed box in the archives’ basement. Tomáš was issued a passport on April 21, 1873.

Tomáš, Marie, and their first two living sons, Josef and Václav (another son, Jan, died in 1871), emigrated in May 1873. Most emigrating Czech families used the German ports of Bremen or Hamburg, and family legend has it that they departed at Bremen and arrived at New York. Unfortunately, Bremen’s passenger lists for 1832 to 1908 were destroyed due to lack of space. I’ve checked the Hamburg passenger lists on Ancestry.com and Leo Baca’s published Czech Immigration Passenger Lists (Old Homestead, 2000), but I have not located a passenger list for this Kohout family and so can’t confirm.

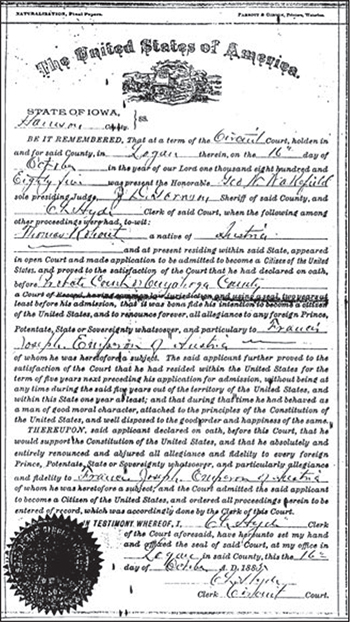

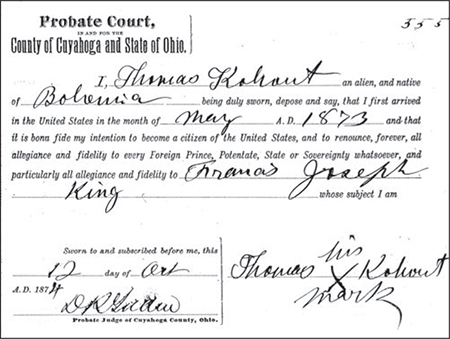

The Kohouts settled first in Pittsburgh, where Tomáš worked at the Carnegie Steel Company for a little more than a year. It was a difficult, degrading job, and the family soon moved to Cleveland to seek better work. Cleveland city directories for 1875 to 1876 and 1877 to 1878 list their address as 150 Rhodes Avenue in an area called the near West Side, or Kuba, that was home to many Czech immigrants. Family legend has it that Tomáš worked on the Lake Erie docks, and the city directories list Tomáš’s occupation as laborer. Tomáš declared his intention to become a US citizen before the Cuyahoga County probate court in 1874; he signed his name with an X. My maternal grandmother, Katherine Kalat Kohout, was born in Cleveland on November 27, 1876, and baptized at nearby St. Procop Church a day later.

Sometime before the 1880 federal census (June 1), the Kohout family moved from Cleveland to the town of Woodbine in Boyer Township, Iowa (they appear there in that census). Marie Kohout (née Kalátová) had a younger sister, Anna, who had previously moved to the same county with her husband, Charles Mickish. This probably influenced Tomáš and Marie, as Czech immigrants tended to move to communities containing other Czechs. The Harrison County, Iowa, circuit court granted Thomas (he had by now Americanized his first name) his final citizenship papers on October 16, 1885. Thomas was a laborer for either the Chicago & North Western Railway or the Illinois Central Railroad, both of which operated through Woodbine; both the 1880 federal census and the 1885 Iowa state census show his occupation as a railroad laborer. On November 24, 1884, Thomas purchased a building lot on Weare Street in Woodbine, upon which he subsequently built a house. To a podruh like Thomas, who had little or no chance of ever purchasing property in the old country, owning property in America must have felt like a real triumph. Three more children were born to Thomas and Mary (she had also Americanized her name) in Iowa: Thomas T., Marie, and Anna.

The Kohout family carried this Reisepass (passport, on the left) with them to America. The strip of paper (at right) is Tomáš’ application for an emigration permit. Originally a single sheet that was separated, both items contain information in German about Tomáš Kohout’s physical characteristics, year of birth, and region, Budweis (České Budějovice).

The circuit court of Harrison County, Iowa, issued Thomas’ final US citizenship papers on October 16, 1885.

Tomáš apparently was not literate in either Czech or English—he signed his name with an X and stated in the 1880 federal census that he could neither read nor write. Marie, however, was somewhat literate in Czech and later in English: I have seen her personal prayer book written in Czech, and federal and state census records show she could read and write in English. As a member of a somewhat higher social class than her husband, it is not surprising that Marie was more literate—she likely had at least some education.

Tomáš likely had a difficult time adjusting to life in America. As an illiterate laborer, he had fewer job opportunities than better-educated immigrants or those with trade skills. In addition, earlier Irish and Germans immigrants had already taken many of the jobs for which Tomáš might have been qualified. Many Czech immigrants had never traveled more than a few miles from their home village. To such people, life in America—whether in a big city or small town—must have been a bewildering experience. Learning a new language and strange customs undoubtedly added to the confusion, and immigrants were usually homesick for the old country and its customs.

Thomas Kohout filed this document in 1874, declaring his intention to become a citizen of the United States and signing his name with an X.

All of these pressures must have eventually gotten to Tomáš Kohout, because he took his own life by hanging on March 16, 1891. By doing so, he left Marie, just a few months shy of her forty-fourth birthday, a widow with several dependent children at home to support and raise. Although she was literate, she had apparently never worked outside the home and was not particularly well-prepared to support her family. Although every federal (1880, 1900, and 1910) and Iowa census (1885, 1895, and 1905) shows no occupation for Marie other than “keeping house,” she managed to raise and educate her children.

Marie died on November 12, 1912. Her obituary stated: “No sacrifice was too great for her if only her children might have a better chance, and this was the real reason of their coming to America. She was a devoted wife and a self-sacrificing mother and a splendid neighbor.”

Thus, the emigration saga of this Kohout family ended differently for Tomáš and Marie. Both left Bohemia with great expectations in search of the American Dream for themselves and their children. It appears that Tomáš may have fallen short in his search, but Marie and her children achieved it admirably in spite of great difficulties.

John Matviya of New Alexandria, Pennsylvania, has been exploring his Slovak family tree for more than three decades—starting in an era when communist policies and hostilities posed a true brick wall for American genealogy searchers. His story, a version of which was originally published in the December 2004 issue of Naše Rodina, shows how studying not just your ancestors, but others in their village, can extend your family tree.

* * *

WHEN I BEGAN MY FAMILY RESEARCH, finding the names of my father’s grandparents seemed impossible. Not only was Czechoslovakia a foreign country and behind the Iron Curtain, I had always been told that my grandfather was born illegitimately and that my grandmother was an orphan. “Forget it,” I was told, even by my own father. Information was just not available back in those days.

All I had to go on were my grandfather’s naturalization papers from the county courthouse and a few word-of-mouth facts and stories. My grandfather Andrew Matviya’s application for a certificate of arrival listed the villages in Austria-Hungary where he and my grandmother were born (Milpoš and Yakovin) and married (Sabinov). It also erroneously listed his mother’s maiden name as Susan Miserak, although she was born a Matvija. My father told me that his father’s father was a “prominent man” in the village named Figura. That was all I knew until I visited Slovakia in June 2000.

At the end of a business trip to Prague and Brno in the Czech Republic, I boarded a train for Košice in eastern Slovakia. Unlike Prague, where many people spoke English or German, Košice had few Western tourists and therefore few English speakers. I would have been totally lost had it not been for a local woman I met in Pittsburgh the previous summer. Slavka, my Slovak friend, wanted to ensure a pleasant visit to Košice and eastern Slovakia. Along with her boyfriend and youngest son, she drove me from Košice to the three villages listed in my grandfather’s papers, more than an hour north in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains.

We first climbed the single lane road to Jakovany where my grandmother Mary Kočis was born. As would become the pattern, my interpreters first approached people working in their garden and asked them if they knew anyone with my grandparent’s last name. We were directed up the road to the home of Juri (George) Kočis. There we stood outside the gate while Slavka’s friend reviewed with George the names in my small family tree. When George recognized one, his garden gate opened wide. He invited us to sit at a lawn table while George showed me his own papers and pictures—including a birth certificate of his grandfather Michael, which listed Michael’s parents as the same couple known to be my grandmother’s parents. George and I realized we were second cousins. To celebrate our meeting, George poured us a large shot of homemade plum brandy (slivovitz), then a second. I wrote down as much of the family information as he could provide. Before leaving the village, George sent me to another second cousin, Michael Kočis. Once he knew we were related, Michael was equally friendly; he shared more photos and information, along with smoked ham, bread, and pivo, a local beer.

Errors in Andrew Matviya’s application for a certificate of arrival indicate that someone else filled out the form. Despite the mistakes, the record contained helpful clues.

We moved on from to my grandfather’s birth village, Milpoš, two valleys to the west. When the two women in their garden heard the question, “Do you know where any Matvijas live?” they laughed and told my friend, “Go knock on any door—Matvijas are everywhere!”

While Slavka’s friend went to seek out someone who might know of my grandfather, she and I meandered around the small cemetery behind the town’s Greek Catholic church. The first stone I came upon bore the name Jan Matvija (my own name in Slovak). A nearby stone was marked Andrew Matvija. Not only I did I see many stones bearing my last name, but others with the surnames of Miserak and Figura. Apparently, just as many people with these names still lived in the village, but none were old enough to remember my grandfather or his mother. I was just another Matvija, and in their world, “Matvijas are everywhere!”

All I expected from this trip was to visit my grandparents’ villages, and I had already found so much more. To my surprise, even more was yet to come. Slavka called Sunday night to say that she was sending her sixteen-year-old son, Kuba, to help me find the state archives in Prešov and serve as my interpreter on Monday. He was fantastic at both. Kuba did all of the talking, and soon I was looking through books of nineteenth-century birth and death records. I found the baptismal records of not only my grandmother and her brother, but more of their siblings and even their godparents. I also was shown a village census from 1869 that listed the birth years of my grandmother’s parents and the name of her grandmother, Anna Kočis, born in 1789.

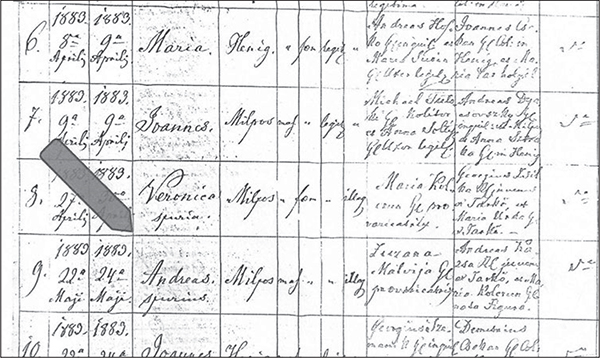

Reading through the birth records of Milpoš’ Greek Catholic church, I soon found my grandfather’s name and birth date, along with the name of his mother, Susana Matvija (no father was listed).

Other records showed that two years after my grandfather’s birth in 1883, Susana married Mathias Miserak. After giving birth to four more children who did not survive beyond their second birthdays, Susana herself died. Mathias remarried within a year. Suddenly the names started to make sense. No wonder no one in today’s Milpoš knew of my grandfather: he probably lived with a family called Miserak, then moved in with his grandparents. Few Matvijas would have had contact with him.

The 1869 census listed Susana’s parents: John Matvija and Anna Surin. My visit to the archives had confirmed the names and birth dates of my great-great-grandparents.

Not long after my trip to Slovakia, I acquired the microfilm of those same church records and the 1869 Hungarian census at my local FamilySearch Center. Understanding the utility in being aware of family “clusters,” I transcribed all the Milpoš records into a database and began compiling a village “family tree.” The census showed that Milpoš had only thirty-five houses in 1869. Susana Matvija’s family lived in house No. 25. Her father was occupied as a tenant farmer, as were all but two of the “heads of household” in the village. Those two were “land owners,” and in house No. 29 was John Figura, a “prominent man” just four houses away from Susana’s. This Figura had three sons about the same age as Susana. I suspected that one of them was my great-grandfather, but it would be another ten years before I learned that DNA might help me prove it.

A Y-DNA test would help only if other close male relatives from my paternal line also tested. For years, I posted queries to genetic bulletin boards and Facebook, seeking men with the surname Figura. Finally I got a response from two Slovaks, one named Joseph Figura, the other Nick Adzima (whose mother was a Figura). Joseph could take the Y-DNA test, but Nick had the paperwork to help: a document trail showing that his mother descended from John Figura of Milpoš.

This Greek Catholic birth register lists the birth and baptismal dates for Andrew, the illeg, plus his mother’s name and birth information and the names of his godparents.

While building this family tree, we were also building trust and convincing ourselves that we were all cousins. Both DNA and paper records confirmed that the Figuras and I were second cousins, once removed, but which Figura is my great-grandfather?

Despite visiting the homeland, networking and cooperating with distant cousins, and taking DNA tests, I still don’t have all the answers. Heritage travel, DNA testing, and traditional genealogy have all helped me learn about my family’s history, but I still have questions about my ancestors. That’s the great thing about genealogy—you’re never finished.