I lived in a bedsit — in the early 1990s, in the UK. It was a bedroom, sitting room and kitchen rolled into one. About 120 sq ft worth of space containing just seven items: a single bed, a two-door wardrobe, a table measuring 1m by 0.5m, a chair, an electric hob with two hotplates, a three-foot tall refrigerator and a sink with some counter-top space that supported the cooker hob. The bathroom and toilet were in the common area.

This little hole stood in the prime postal district of SW7 London — South Kensington and Knightsbridge. The street address: Emperor’s Gate, off Cromwell Road. A mini slum within a prestigious neighbourhood of luxury Victorian-era homes. As a poor student struggling with a British pound almost three times the Singapore dollar, that was the best I could afford. I saved some money by walking to college, even in the wet, slushy and grey winter days.

Having lived in a tiny space for about nine months during my first year in London, I am curious about the recent fascination Singaporeans have with the 350 sq ft apartments labeled as ‘Mickey Mouse’ units. Compared to these ‘shoebox’ units, I would label my London bedsit a ‘Mud Wasp’ unit.

The low price quantum — that is, affordability — is often quoted as a reason for the strong take-up of such apartments. In my view, that is only half correct because investors seem to be willing to bear with the much-higher-than-average price per sq ft for these apartments.

I believe that the other half of the equation is this: investors simply do not know what products they are buying into. Let’s take an analogy from the car market. We do not see strong take-up rates for buying Chery QQs and Perodua Kancils despite the very low entry price of about $48,000 a car. In fact, I see many more Toyota Corolla Altis, at $85,000 each, on the roads.

Why is the easy affordability of a Chery QQ not creating a flood of demand for such cars? The reason is this: buyers can test-drive the cars, sit inside an actual car, drive it around and feel the comfort and the space. Buyers are not sitting in mock-up cars that have doors removed to create a sense of space or full length mirrors on the insides to make the interiors look bigger.

’Shoebox’ apartments are selling well because few investors know what these units look like physically. Few of us have friends and relatives who live in such units. Fewer have lived in apartments of less than 500 sq ft.

Of the roughly 2,800 apartments below 500 sq ft that were sold by developers in the last 10 years, only about 1,000 have been completed and are available for us to physically experience the size and space. About 50 per cent of these developers’ units were purchased by investors with HDB addresses — not surprising, considering the prices of these units are usually lower than the prices of five-room HDB flats.

The showflats of residential projects that have a mix of large and small units do not feature the shoebox units as these generally sell out fastest, at the highest price per square foot (psf) levels and to investors who have relatively little experience with apartments of such sizes.

Residential projects consisting solely of shoebox units may be launched with simple sales galleries, that is, without mock-up apartment units or show units. Investors buy off-the-plan simply by considering the materials used, the drawings, and again, the low absolute dollar value of the units.

However, there are a handful of projects that do feature full-sized shoebox units in the showflats. These show units, while true to the floor plans in terms of size, come with interior designs and modifications that make them appear larger than they should be, such as the use of mirror walls.

As investors walk through the showflat with responsible sales agents, they might hear one or more of the following:

I am concerned that many have recently invested in a relatively new product which may not find widespread acceptance when completed.

Fewer than 1,000 shoebox units were sold by developers from 2001 to 2008. But in the last 24 months (2009 and 2010), 2,000 shoebox units were sold. When they are completed in 2011 and beyond, market acceptance of this category of residential product will be tested in terms of tenant quality and profile, rental yields, maintenance of the estate, as well as returns on investments, among others.

The term ‘shoebox’ apartment is generally defined as a studio or a one-bedroom apartment that has less than 500 sq ft of strata area. The area includes, say, about 15 per cent allocated to balconies, planters, bay-windows, aircon ledges and, in some cases, bomb shelters. Therefore a 380 sq ft one-bedroom unit might have a real usable space of about 330 sq ft in the living/dining areas, kitchen and bedroom.

How do the economics stack up? Per square foot prices and rentals generally go up when the sizes of the apartments go down. So in several recent launches, the one-bedroom units fetched, for example, $1,200 psf while the three-bedroom units transacted at below $1,000 psf — a 20 per cent premium that arises because the smaller unit with a lower selling price quantum has a wider reach.

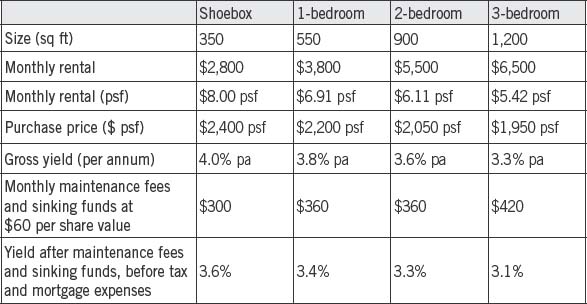

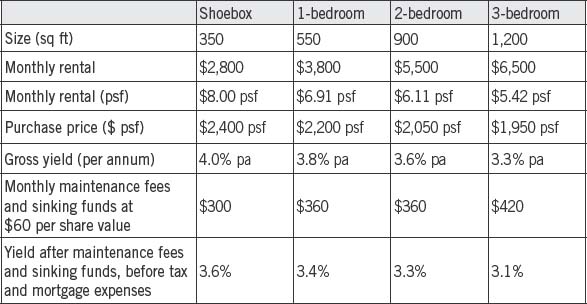

As for rentals, let’s take a hypothetical example, say, in River Valley today. A one-bedroom 550 sq ft unit may lease for $3,800 a month, a 900 sq ft two-bedroom unit may lease for $5,500 a month, while a 1,200 sq ft three-bedroom unit, $6,500. The rentals per square foot increase as the sizes of the apartments drop (see Table 12).

However, up to a point, the equation fails to apply. In this example, a 350 sq ft studio unit in River Valley may, for instance, fetch about $2,800 per month in rental. However, that is near the limit of how high rentals can go for shoebox units. This unit is similar in size as the deluxe hotel rooms in the River Valley area.

If we tried to push rentals beyond $3,000 per month, that is, above $100 per day, it may be more economical for the low-budget tenant to take a long-term let with a hotel around River Valley, given the more flexible lease terms that include daily housekeeping, electricity, fully furnished/equipped rooms and probably complimentary laundry. He would also save on rental whenever he travels out of Singapore.

Table 12 Comparison of rentals

(Source: IPA)

As for costs, if every single apartment in a development were shoebox-sized units, their share values would be five for every apartment.4 The maintenance fees and sinking funds for the common areas and shared services would be equally borne by all the owners of the development. However, if a project had some shoebox units mixed with larger-sized two- to four-bedroom units, then the shoebox units will contribute proportionately higher maintenance fees and sinking funds.

So, when we sum them up, the yields — net of maintenance fees and sinking funds — become narrower between shoebox units and their larger-sized cousins. Should the economy weaken and vacancies run high, and normal two-bedroom units are available for rent at $3,000 to $4,000 per month, how would shoebox units stand up to price competition?

I wonder what new social challenges may prevail in the future for those developments that contain a wide mix of units. In developments where the $600,000 shoebox or one-bedroom units were bought by investors and the $2 million four-bedroom units purchased by owner-occupiers, will the low-budget tenants from the shoebox units make good neighbours for the rest?

Will there be poor cousins in a rich compound just like I was a poor student living in a 120 sq ft bedsit within the posh Kensington neighbourhood? In such a mixed development, will investor-landlords be willing to contribute that little extra to maintenance and sinking funds as compared to house proud owner-occupiers?

We’ll just have to observe as such heterogeneous projects, most still under construction today, become mature and fully occupied estates over the next five to 10 years.

From a list of about 130 projects that have shoebox units, it is interesting to note that the most common name used is ‘suites’ (see notes for Table 13). This is merely terminology and not to be confused with hotel suites (which are generally bigger than shoebox units) nor with several luxury projects that do not have shoebox units, such as Marina Bay Suites, Paterson Suites and Nathan Suites.

In land scarce Singapore, space is a real luxury. While trying to improve the quality of life, we also need to maximise the use of every square foot of land. HDB flats have risen up to 50 storeys. Shrinking apartment sizes is another way to satisfy the demand from more, and smaller, households. The proliferation of shoebox apartments should be an expected consequence of the steadily increasing population density.

I sincerely hope that we will never see Singapore’s condominiums slide to Hong Kong’s cramped apartment sizes, or London’s bedsit-sized units. The goal is to achieve a balance between quality living and the best use of space.

Perhaps shoebox developments of the future will contain bathtub-sized swimming pools, a two-stroke lap pool in the sky garden, parking lots for QQs, the use of disposable BBQ pits, gyms that are fully mirrored with a single fold-away multi-station fitness equipment supplied by mail order (call within the next 30 minutes...) and a vertical fitness station provided via jogging tracks alongside the staircase, just to name a few innovative features. Cramped spaces anyone?

Table 13 Number of transactions (new sale, less than 500 sq ft)

* Includes over 100 projects such as Parc Sophia, The Verve, Lumiere, The Lenox, Soho 188, Hundred Trees, Optima @ Tanah Merah, Soleil @ Sinaran, Caspian, 8@Woodleigh, Newton Edge, City Loft, Suites @ Katong, Suites @ Changi, Suites @ Kovan, Suites @ Topaz, Centra Suites, Dunearn Suites, RV Suites, Suites 123, Mount Sophia Suites, Kembangan Suites, Lincoln Suites, The Ford at Holland, etc.

(Sources: URA Realis, IPA)

4 Under current share value allocation rules, apartments of less than 50 sq m (538 sq ft) are allotted share value of five, larger apartments up to 100 sq m (1,076 sq ft) are allotted six, and so on, increasing by one share for every additional 50 sq m of strata area.