Heritage supporters and conservationists may lament that the rapid growth of Singapore has led to the loss of communities such as the Peranakan cluster in Katong or the foreign military neighbourhood in ‘Ang Sar Li’ (Serangoon Gardens), or perhaps the loss of iconic monuments such as the Van Kleef Aquarium and the National Theatre at Fort Canning, as well as the red-bricked National Library along Stamford Road.

Rejuvenation, renewal and growth simply mean that some things have to be taken down to make way for new and better things. We might therefore measure the price of progress by the things we have left behind. However, what happens if progress leads us towards future pains that outweigh the benefits of renewal? Is that progress?

The landscape of Singapore has undergone dramatic changes in the last five years with massive projects around Marina Bay (the Barrage, Marina Bay Sands, the upcoming Gardens by the Bay, and new office and residential towers) and in Sentosa (more than 2,000 residential units in Sentosa Cove, a new world class marina yacht club and Resorts World Sentosa which hosts the largest Universal Studios theme park outside of the USA).

To match the multi-billion dollar investments, the government is investing close to $2 billion to build the infrastructural base for Marina Bay, including the Common Services Tunnel which will distribute utilities to all users, a rapid transit system (formerly called Downtown Extension of the Circle Line), a new waterfront promenade and a bridge.

Singapore’s success story is supported by a high-quality and well-oiled infrastructure. Foreign multinationals are confident about Singapore, often ranking the island republic as a top investment location in a multitude of surveys.

The en bloc fever that had begun in 2005 is still modifying our streetscape today. While earlier en bloc deals such as Newton Heights (March 2005) and Bo Bo Tan Gardens (June 2005) have already been transformed into Newton One and The Regency at Tiong Bahru respectively, many others are still being re-constructed and a handful are not yet demolished.

There were more than 200 en bloc transactions in the 36-month period of January 2005 to December 2007. More than 12,000 homes have been or will be demolished and replaced with more than 25,000 new and higher density residential units. We estimate that the replacement ratio is about 2.2 to 2.5 times, especially since shoebox units have become more popular with the slowdown in developers’ sales in 2008.

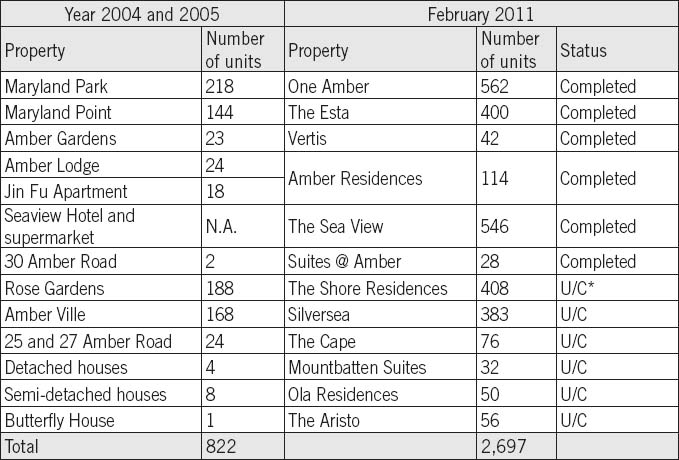

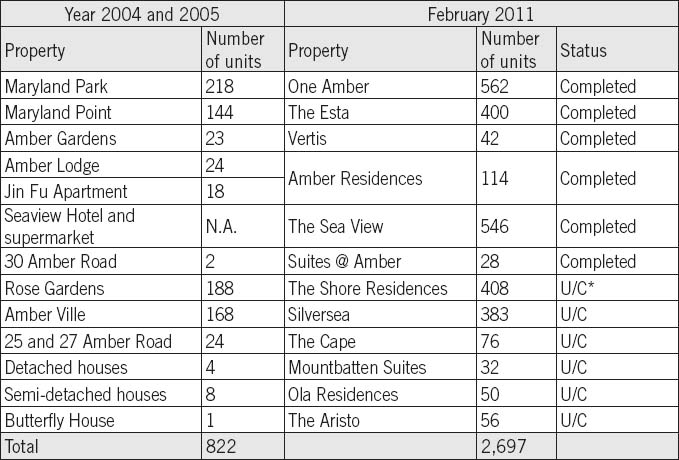

In certain locations, the rejuvenation is more extensive. Take for example the cluster around Amber Road and Mountbatten Road in Katong. In 2005, the neighbourhood consisted mainly of old houses, or low density apartments with surface parking lots, where the average plot ratio was around 1.0 to 1.5. Most of the owners of these old developments and houses enjoyed windfalls when they sold to developers to re-develop the sites with plot ratios of 1.4 to 2.8. See Table 17.

A total of 822 homes will eventually be replaced with 2,697 homes; in other words the density of homes has increased by 3.3 times. To date, more than half, or about 1,700 units, have been completed and this is already more than twice the number of homes that have been demolished. The gross development value of the new homes, assuming every unit is sold, would amount to over $3 billion, given that the average price of each of the 2,697 units is well over $1 million.

Standing at the junction of Mountbattan Road and Amber Road, with our backs against Katong Shopping Centre and looking around and beyond the scattered projects still under construction, we can see that the landscape is modern. It looks like a brand new neighbourhood, impressive and resplendent with the towering blocks of The Esta, One Amber, The Sea View, and many others.

Table 17 Re-development projects in Katong

* U/C = Under Construction

(Source: IPA)

Blocked views from Katong Shopping Centre

The view has, unfortunately, become cluttered. The neighbourhood has become less spacious and I am uncertain if we have made progress in our living environment or whether we have traded off too much. Despite the $3 billion development value, one thing that remains largely unchanged is the traffic capacity of Amber Road and Mountbatten Road. Although there has been some road widening along certain sections of these roads, we can expect traffic to become heavier as projects get completed.

Some may point out that the authorities are investing several billion dollars into the Eastern Region Line (ERL) of the MRT to serve Tanjong Rhu, Marine Parade and Siglap through to Bedok South and Changi Point Ferry Terminal. The exact locations of the stations have not been announced but the ERL is targeted for completion in 2020. Once construction of the new line begins, would the roads in Katong become more congested, right up till 2020? And would an MRT station within 100 metres of the neighbourhood actually lead to a lower car population within the neighbourhood?

The Katong cluster is not an isolated case. Several streets that used to be quiet enclaves are now transforming into high density neighbourhoods. Some examples are St Thomas Walk, the Cairnhill cluster (comprising Cairnhill Road, Cairnhill Rise and Cairnhill Circle) and the Balestier-Thomson junction (comprising Jalan Raja Udang and Jalan Datoh). The increase in the density of homes will surely lead to growth in traffic. We need to match these with wider roads or with alternative forms of people-mover systems that can ease congestion.

However, during the period of constructing new infrastructure or improving on existing infrastructure, residents will have to live with the inconvenience. For example, the neighbourhood at the Balestier-Thomson junction may be constrained by the seven-year construction of the North-South Expressway from 2013 to 2020.

Without contributing plausible solutions, this discussion would merely be unconstructive criticism and nitpicking levelled at the high price of progress.

One suggestion to alleviate future traffic problems around en bloc projects is for the road line and building setbacks of the redevelopment to be adjusted to cater for the potential widening of roads.

Developers invested in en bloc projects should not be penalised and should be allowed to maintain the total Gross Floor Area (GFA) prescribed by the plot ratio and land size. However, at point of submitting their plans for approval, the authorities can amend various parameters to cater for future road widening. Where setbacks have to be increased, developers could perhaps be allowed to increase the height of the project.

With 20-20 hindsight, this suggestion, had it been implemented in 2005, would have allowed for wider roads at St Thomas Walk or Cairnhill Circle, leading to smoother traffic flow. And maybe to better fengshui?

I am in favour of urban renewal and progress. The challenge is to maintain ample space while Singapore accommodates more and more people, well beyond the current population density of 7,000 per square kilometre. I support renewal at a more measured pace, one that allows Singapore to maintain a high quality environment with ample space for each of us. And renewal that is more thoughtful.

As the 2007 episode over the conservation of the Butterfly House in Amber Road has shown, we need to be more definitive about what is good value and what ought to take higher priority. Economics and returns on investment should not always take top spot in the list of parameters for urban renewal. If the decision were mine, I would put ‘space’ near the top of every list. I would also choose to preserve the Butterfly House in its entirety.

Can we factor in the luxury of space for ourselves and our future generations?