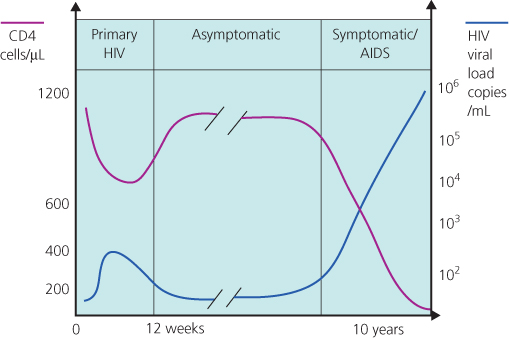

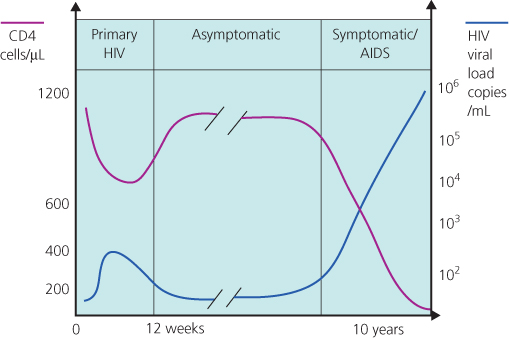

Figure 5.1 Association between virological, immunological and clinical events and time course of HIV infection.

Chapter 5

Clinical Staging and Natural History of Untreated HIV Infection

Overview

HIV infection causes a spectrum of disease

The Centers for Disease Control in the USA developed the most widely used classification for HIV disease based on clinical symptoms and signs, the presence of certain conditions and the degree of immunosuppression as measured by the CD4 lymphocyte count

Untreated HIV infection leads to an inexorable decline in CD4 cell counts leading to immunosuppression and opportunistic infections

Factors influencing disease progression include older age, higher plasma viral loads and severely symptomatic primary HIV infection

Infection with HIV causes a spectrum of disease ranging from primary HIV infection (PHI) in the very early stage of infection to, in the absence of cART, diseases associated with immune suppression and eventually death. Between PHI and the development of AIDS there is a progressive loss of CD4 lymphocytes with the patient's CD4 falling by between 50 and 100 cells/µL per year. Individuals are often asymptomatic during this phase. The median time from infection to developing AIDS in untreated people is 10 years (range 18 months to 25 years). The rate of progression can vary significantly, with some individuals progressing to AIDS within a couple of years (‘rapid progressors’) and others maintaining a good immune system more than 10 years later (‘slow progressors’). Higher plasma HIV viral loads and severe symptomatic PHI are associated with faster progression to AIDS. Less than 1% of patients will be able to control HIV viraemia without combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and these patients rarely develop immune suppression or AIDS. These individuals are known as ‘elite controllers’. Some children with vertically transmitted HIV are surviving with asymptomatic infection for more than 20 years.

Prior to the availability of antiretrovirals, the mean survival time after an diagnosis of AIDS was less than 2 years. The introduction of cART has revolutionized prognosis and when commenced early in HIV infection the life expectancy with HIV infection may approach normal.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA developed the most widely used classification for HIV disease based on clinical symptoms and signs, the presence of certain conditions and the degree of immunosuppression as measured by the CD4 lymphocyte count. This was updated by the CDC in 1993 to classify all HIV-infected persons with CD4 lymphocyte counts of <200 cells/µL as fulfilling the AIDS-defining illness criteria (Boxes 5.1–5.3). The

classification of the stage of HIV infection provides a framework for categorizing morbidity and immunosuppression and is an important tool for HIV surveillance. Prior to the widespread availability of cART (which has the ability to restore HIV-induced immune suppression) it was very important as it helped to estimate an individual's prognosis and to make decisions about when to start opportunistic infection prophylaxis and available cART.

Category A

Category B

Category C

PHI is the time between initial infection to the development of antibodies against HIV. During this period the individual frequently develops symptoms compatible with an acute viral infection. This is also known as ‘HIV seroconversion illness’.

The clinical presentation ranges from a mild glandular fever-like illness with a rash to an encephalopathy. Common symptoms and signs are shown in Box 5.4. Severe symptoms are rare. The onset of PHI symptoms within 3 weeks, symptoms that last for longer than 2 weeks and central nervous system involvement are associated with rapid progression to AIDS. The differential diagnosis of a mild seroconversion illness is protean and, without a high index of suspicion and a history indicating relevant risk behaviours or factors, the diagnosis may be missed. It is particularly important to exclude secondary syphilis.

*Erythematous, maculopapular rash mainly on face and trunk with or without mucocutaneous ulcers of mouth, oesophagus or genitals.

The appropriate diagnostic tests for PHI that should be carried out on serial blood samples include tests for HIV antibodies and antigen. All laboratories in the UK should now be using a fourth-generation combined antibody/antigen test which should detect primary infection, i.e. within the first few weeks (Chapter 3).

At the time of PHI there is sometimes a high rate of viral replication, leading to a transient rise in HIV viral load with concomitant immunosuppression due to a short-lived (occasionally dramatic) fall in the CD4 count (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Association between virological, immunological and clinical events and time course of HIV infection.

Rarely, this may result in manifestations of HIV disease normally seen later in the disease, e.g. oral candida (Figure 5.2) leading to occasional diagnostic confusion as to the stage of HIV infection. Sometimes, this can be resolved by taking a full sexual history to establish when HIV might have been transmitted. Newer virological assays should also be used to identify HIV seroconversion (see Chapter 3) together with serial viral load and CD4 cell assays. Over time, after PHI, the viral load will fall and the CD4 count rise. During PHI initiation of cART is usually only considered in the presence of severe symptoms (especially central nervous system involvement), an AIDS-defining diagnosis or severe immunosuppression (CD4 < 350 cells/µL).

Figure 5.2 Oral candida.

There is considerable interest into the efficacy of cART during PHI to decrease long-term damage to the immune system, delay disease progression and prevent transmission (see Chapter 19). It is postulated that HIV may be more susceptible during PHI to cART due to the relatively low diversity of replicating virus particles, the reduced ability of the predominantly non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) strains of virus to infect a wide variety of cell types and the enhanced immune response seen at this time. However, if not started early in the course of PHI (i.e. within 6 months) the theoretical advantage may be lost and, in any case, has to be balanced against an uncertain outcome, drug toxicity, adherence difficulties and the possibility of developing resistant virus and limiting future treatment options.

Individuals with PHI are usually extremely infectious at this stage due to very high levels of HIV within the body; therefore, contacts need to be carefully screened and followed up, PEP offered if appropriate and advice given to avoid onward transmission.

After PHI, HIV antibodies continue to be detectable in the blood. The amount of virus in blood and lymphoid tissues falls to significantly lower levels than seen in PHI and the rate of HIV replication slows, although it does not cease. CD4 counts are generally above 350 cells/µL. This phase may persist for 15 years or more (Figure 5.1). The role of cART during asymptomatic infection is discussed in Chapter 19.

Transmission is still possible despite the viral load being lower than PHI and, as the progression rate to AIDS varies widely, monitoring should continue to ensure that cART is offered at the optimum time.

This is defined as lymphadenopathy that persists for at least 3 months, in at least two extra-inguinal sites and is not due to any other cause. The differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy in HIV is wide and includes Mycobacterium TB and lymphoma. Mediastinal and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy are not part of this syndrome and require further investigation to exclude infection and neoplasia. The presence of persistent generalized lymphadenopathy does not affect disease progression. This alone is not an indication to start HIV treatment.

The progression of HIV infection results in a decline in immune competence that occurs due to the increased replication of HIV from sites where it has been latent. The exact triggers for this reactivation are still poorly understood. As the disease progresses, infected persons may suffer from constitutional symptoms, skin and mouth problems (see Figures 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, 5.5 and Chapter 14) and haematological disorders, many of which are easy to treat and alleviate. A decrease in HIV viral load in response to the introduction of cART often corresponds to a complete or partial resolution of these symptoms.

Figure 5.3 Oral hairy leucoplakia.

Figure 5.4 Unidermatomal shingles caused by varicella zoster.

Figure 5.5 Perianal herpes simplex virus.

Common constitutional symptoms associated with symptomatic HIV infection include malaise, fevers, night sweats, weight loss and diarrhoea. The exact criteria for diagnosing the AIDS-defining HIV wasting syndrome are the combination of 10% weight loss from baseline and one of fever or diarrhoea lasting at least 1 month. Many patients find these symptoms worrying and debilitating and they should always be investigated to diagnose treatable causes other than HIV.

Haematological abnormalities are common in HIV disease and usually have no adverse effect. These include lymphopenia, moderate neutropenia (which may be linked to ethnicity), a normochromic, normocytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Bone marrow biopsies usually indicate trilineage dysplasia and are not routinely indicated in the absence of coexisting fever, diarrhoea or lymphadenopathy, which may indicate mycobacterial infection or neoplasia. Many of these abnormalities wholly or partially resolve after cART is initiated.

The defining features of AIDS are the ‘persistent and profound selective decrease in the function as well as number of T lymphocytes of the helper/inducer subset and a possible activation of the suppressor/cytotoxic subset’. However, alongside this immunosuppression an immune dysregulation occurs which affects natural killer cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells and CD8 T-cell function. Owing to this complex immunological interplay, HIV-related disease processes can still occur at ‘high CD4 counts’ and so the clinical course of patients with these conditions will benefit from the initiation of cART in order to optimise immune control.

Examples include:

Predicting how soon a patient will progress to symptomatic disease or AIDS is an issue with which physicians continue to grapple. Variables associated with rapid disease progression and some host and viral factors which appear to be protective are shown in Box 5.5.

Factors which increase the rate of progression

Factors which appear protective

Many laboratory indices have been used as prognostic indicators, both to evaluate disease progression and treatment efficacy. The most widely used are the CD4 absolute lymphocyte count or percentage and the HIV viral load. At least two CD4 measurements should be obtained before initiating prophylaxis for opportunistic infections or cART as the CD4 count is subject to diurnal and seasonal variation and reduced by intercurrent infection. Likewise, at least two viral loads, from the same laboratory using the same assay, should be obtained to avoid interassay variation.

The effect of prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, e.g. cotrimoxazole for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) and toxoplasmosis, has been shown to delay the onset of AIDS and change the pattern of disease manifestations. The CD4 count is the most important prognostic indicator in determining the likelihood of particular opportunistic infections (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Association between major clinical events in HIV infection and CD4 cell count—potential indications for prophylaxis.

| CD4 cell count (cells/μL) | Clinical event |

| <200 | Pneumocystis pneumonia |

| <100 | Toxoplasmosis |

| Cryptococcosis | |

| Candidal oesophagitis | |

| <50 | Disseminated cytomegalovirus |

| Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex |

Centers for Disease Control. 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS among Adolescents and Adults. MMWR 1992; 41(RR17).

Health Protection Agency. 30 years on. Health Protection Report 2011; 5(22); (www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2011/news2211.htm).

Health Protection Agency. HIV in the United Kingdom: 2010 Report. Health Protection Report 4:26 (www.hpa.org.uk).

Health Protection Agency. Numbers accessing care: national overview. (www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1203064766492).