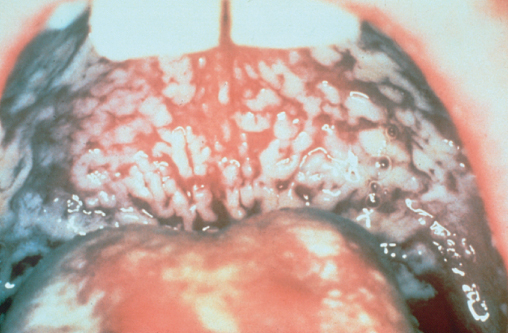

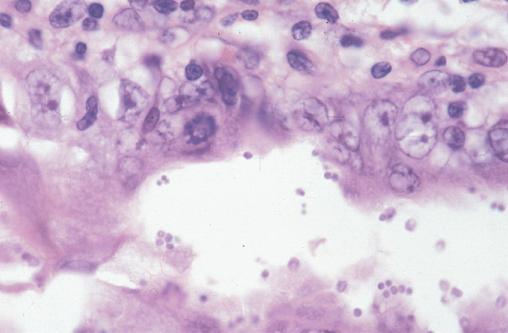

Figure 10.1 Oral candida.

Chapter 10

The Gut and HIV

Overview

In the pre-cART era infections and tumours of the gastrointestinal tract were common

With the advent of successful therapy these have become less prevalent and the commonest gastrointestinal (GI) symptom is diarrhoea as a side effect from antiretroviral medication

Individuals unaware of their HIV diagnosis may present with GI symptoms and consideration of HIV testing should be considered if symptoms remain unexplained

In the HIV population many abdominal symptoms may be related to non-HIV-associated causes and referral to an experienced gastroenterologist may be needed

The gastrointestinal tract can be affected at all stages of HIV infection and symptoms related to the gut are the most frequent in individuals living with HIV. Prior to the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), the majority of these symptoms were associated with opportunistic infections and HIV-related tumours. However, with the success of cART the majority of gastrointestinal disease is now aetiologically similar to that of the HIV-negative population except for toxicities related to antiretroviral agents. It is important, however, that all physicians are aware of the possible manifestations of HIV-associated disease of the gastrointestinal tract as these may be the first clinical manifestation of symptomatic HIV disease and should prompt the clinician to offer HIV testing. Additionally, gastrointestinal (GI) problems can occur in individuals taking cART if there is lack of HIV virological control or persistent immunosuppression.

In patients with HIV infection, the risk and pattern of GI involvement alter with the level of immune function, and in particular with the CD4 count. Whereas some are AIDS-defining conditions (Box 10.1) others may occur at any stage of HIV disease. The gut mucosa is an important route of entry of HIV and in those practicing anal intercourse it is important to exclude other sexually acquired infections which may affect the lower gastrointestinal tract.

Infections

Tumours

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and odynophagia (pain on swallowing) are common symptoms in those with late stage untreated HIV disease, but these symptoms may occur at any stage of HIV infection. HIV seroconversion may occasionally be complicated by aphthous ulceration of the oesophagus with the development of these symptoms, but generally more classical symptoms of seroconversion will also be present.

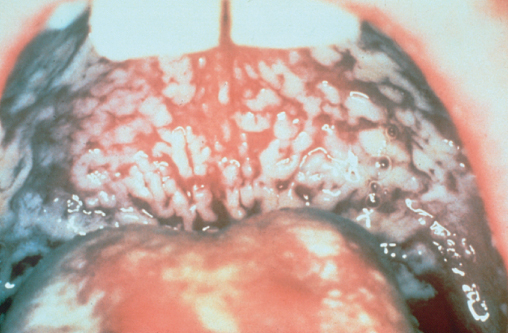

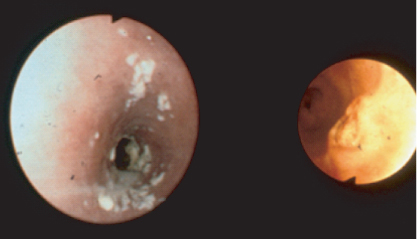

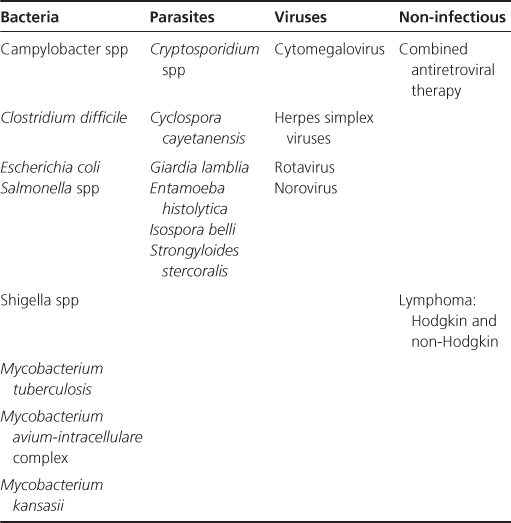

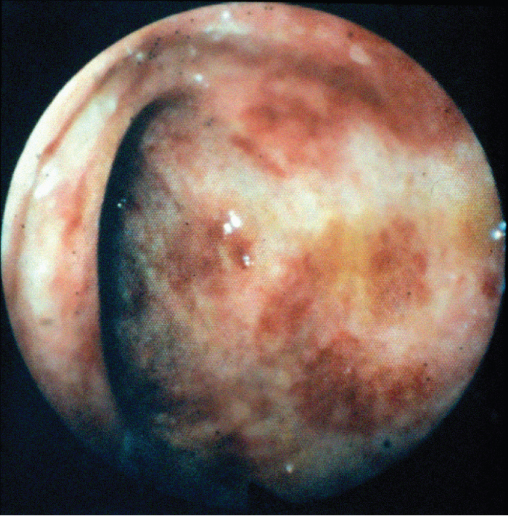

The commonest cause of dysphagia and odynophagia in HIV disease is oesophageal candidiasis. In the majority of cases plaques of candida are also present in the mouth (Figure 10.1) and the diagnosis can be inferred, with symptoms usually resolving following antifungal therapy. Where the diagnosis is in doubt or symptoms do not resolve with treatment an endoscopy should be performed where the appearances of oesophageal candida are typical (Figure 10.2) and can be confirmed by brushings or histology. Standard treatment for oesophageal candida is with an azole most commonly fluconazole. Occasionally candida species may be resistant to fluconazole and may respond to itraconazole. In those unable to swallow, intravenous therapy with amphotericin B or caspofungin is required.

Figure 10.1 Oral candida.

Figure 10.2 Fibreoptic appearances ofoesophageal candida.

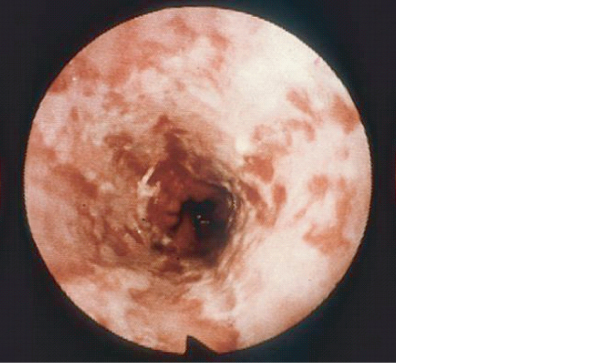

A minority of HIV positive individuals with oesophageal symptoms have other opportunistic infections. Herpes simplex (HSV) infection and cytomegalovirus (CMV) may both produce distal oesophagitis and typically occur at CD4 counts below 100 cells/µL, and often co-exist with candidiasis. CMV is associated with discrete ulceration with rolled edges resembling a carcinoma (Figure 10.3). CMV oesophagitis is treated with ganciclovir intravenously, and HSV oesophagitis by intravenous aciclovir. All patients with CMV oesophagitis should be screened for retinal disease. Apthous ulceration of the oesophagus may be due to an unknown virus or HIV itself and usually responds to Thalidomide or intralesional or systemic steroids. Kaposi sarcoma (KS), and more rarely lymphoma, may affect the oesophagus.

Figure 10.3 Cytomegalovirus affecting the oesophagus: endoscopic appearance demonstrating ulceration in oesophagus.

In the pre-cART era nausea and vomiting were primarily associated with opportunistic infections most commonly those that cause HIV diarrhoea (Table 10.1) and tumours, both KS and lymphoma, of the stomach. Nowadays they are most commonly associated with cART especially, but not exclusively, with ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors. Nausea and vomiting are linked to non-adherence to cART regimens and should be actively treated. The possibility of these symptoms being secondary to HIV related CNS infection or tumours should always be considered.

Prior to the introduction of cART it was estimated that 30–70% of individuals experienced diarrhoea, which was primarily linked to infections (Table 10.1) and tumours. cART has greatly reduced the prevalence, although diarrhoea may be a common side effect of cART itself. All individuals experiencing diarrhoea should have stool cultures sent, and if no cause is found and the diarrhoea continues should be referred for further investigation, which most commonly would include sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy and possibly upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Table 10.1 Major causes of HIV-related diarrhoea

Patients presenting with a sudden onset of diarrhoea may have any of the causes of chronic diarrhoea (see below) but are more likely to have either a bacterial or viral infection.

Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter are enteropathogens which occur with increased frequency in HIV-infected individuals. The illness is usually more severe than in the immunocompetent, is more likely to relapse and infections are caused by less virulent species. Salmonella and Campylobacter are associated with food contamination and are prevented by good food hygiene and thorough cooking. Shigella infection is both water-borne and sexually transmitted, but is comparatively rare. All three organisms respond to ciprofloxacin, although there are increasing reports of resistance. Clostridium difficile is an important cause of diarrhoea and is more common in the severely immunosuppressed but the presenting symptoms are similar. Treatment is similar to that in the seronegative population. Sexually transmitted agents including Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia species, especially Lymphogranuloma venereum should always be considered.

Acute diarrhoea may be caused by rotavirus or very occasionally adenovirus which when it does occur may cause a protracted illness with no known treatment. Herpes simplex infection may present with a severe proctocolitis and acute diarrhoea.

In the pre-cART era chronic diarrhoea was common and was an important contributor to the wasting syndrome (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 HIV wasting syndrome.

The necessary investigations and the likely causes of chronic diarrhoea vary depending upon the degree of immunosuppression as assessed by the CD4 count. With a count of above 200 cells/µL opportunistic infections are unlikely and investigation should be similar to that in general gastroenterology, with the irritable bowel syndrome being the commonest diagnosis.

In those with a CD4 count below 200 cells/µL it is important that HIV-related infections and tumours are always excluded. Possible infectious causes are discussed below.

These are obligate intracellular parasites that occur most commonly in those with a CD4 count below 100 cells/µL. The most common species causing gastrointestinal disease are Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Septata intestinalis, the latter also being associated with renal and corneal damage.

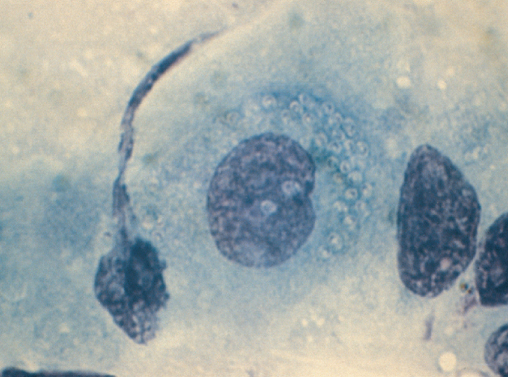

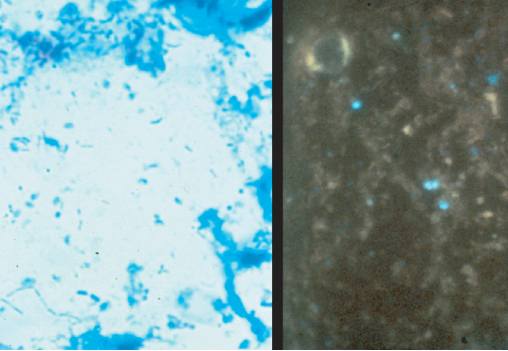

Microsporidial cysts are ingested from contaminated water and in the alkaline pH of the duodenal fluid cysts extrude a thin tube which penetrates the duodenal mucosa like a hypodermic needle and the contents of the cyst are injected into the cell (Figure 10.5). Infection usually produces mild to moderate watery, non-bloody diarrhoea. Stool examination with specific fluorescent stains is usually sufficient for diagnosis (see Figure 10.6) but if stool specimens are negative a small bowel biopsy may be required for diagnosis.

Figure 10.5 Microsporidial cysts (microscopic view using Giemsa stain) (courtesy of Elizabeth Canning).

Figure 10.6 Microscopic stool examination using fluorescent stain showing microsporidial cysts.

Asymptomatic infections rarely occur and like cryptosporidium, microsporidial infection may resolve spontaneously in those with better preserved CD4 counts. Septata intestinalis can be eradicated by albendazole but there is no treatment for Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Successful treatment with cART due to improvement of immune function, leads to eradication of microsporidia with resolution of symptoms.

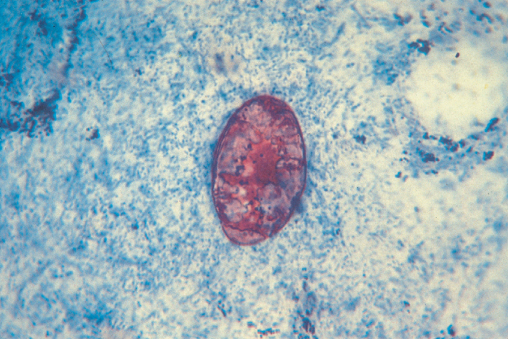

This is a protozoa that commonly infects the immunocompetent producing acute attacks of diarrhoea. However, in the immunosupressed, particularly those with a CD4 count less than 100 cells/µL, it may cause severe chronic diarrhoea often associated with nausea, malabsorption and anorexia leading to rapid and extensive weight loss. The stool volumes in cryptosporidial diarrhoea are variable but in some patients more than 1 L of stool is passed daily. The commonest source is contaminated water and this infection can be prevented by boiling water to destroy cryptosporidial cysts. Diagnosis is by stool examination with auramine and acid fast stains (Figure 10.7). Diagnosis may also be achieved by obtaining colonic or rectal biopsy which may demonstrate oocysts attached to the epithelial cells (Figure 10.8). No treatment has been shown to eradicate cryptosporidium reliably, although paromomycin and nitazoxanide may be utilized. The best therapy once more is cART with restoration of the immune system again leading to eradication and resolution of symptoms.

Figure 10.7 Stained cryptosporidium oocysts using modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain.

Figure 10.8 Rectal biopsy showing cryptosprodialoocysts attached to the epithelial cells.

Although cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection may occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract, CMV colitis is its most common manifestation occurring most commonly in those with a CD4 count below 50 cells/µL. Disease follows reactivation of a previous CMV infection, which is common in the HIV infected population. Classically, patients present with bloody diarrhoea, and the macroscopic appearance at endoscopy is typical of a colitis (Figure 10.9). The diagnosis is confirmed by finding typical viral inclusions on histology of colonic biopsies (Figure 10.10). Complications of perforation or toxic dilatation may occur in a small number of patients. Treatment is with either foscarnet or ganciclovir and relapses are prevented by initiation of successful cART. Active retinal infection must be excluded in all those diagnosed with CMV colitis.

Figure 10.9 Cytomegalovirus colitis: macroscopic appearance at endoscopy.

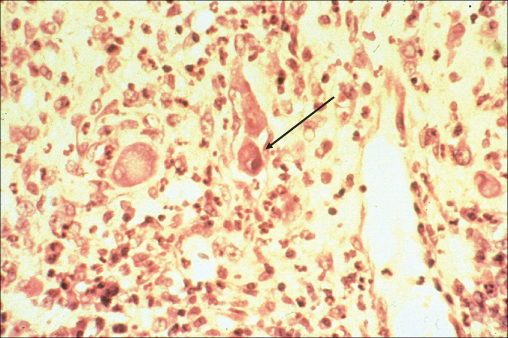

Figure 10.10 Cytomegalovirus colitis: colonic biopsy demonstrating basophilic intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear Halo (owl's eye effect) which isa classical feature of CMV infection.

Other infections associated with chronic diarrhoea include Giardia, which commonly has associated symptoms of nausea, bloating and chronic abdominal pain; Entaemoeba histolytica, which may present with fever, bloody or watery diarrhoea and abdominal pain; Cyclospora associated with prolonged watery diarrhoea; Isospora belli and Strongyloides. Diagnosis is through stool specimen with specific staining and occasionally colonic biopsy is required.

Both KS and HIV-associated lymphoma may occur in the lower gastrointestinal tract and be associated with diarrhoea. Colonic cancer may be commoner than the general population in those who are HIV infected and over the age of 50.

In the cART era perhaps the commonest reversible cause of diarrhoea is drug therapy with non-HIV agents, although it is particularly associated with antiretroviral agents especially ritonavir boosted protease inhibitors. With a now widely available choice of HIV drugs, switching either within class or to a different class of agent will often lead to resolution.

With success of HIV therapy leading to a reduction in opportunistic infections and HIV-associated tumours, non-HIV-associated conditions should always be considered. When there is difficulty making a diagnosis referral to an experienced gastroenterologist is essential. Some conditions associated with diarrhoea may occur more frequently in the HIV population, e.g. malabsorption secondary to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and may be the consequence of long-term antiretroviral exposure.

Abdominal pain is common in the general population and is similarly so in those infected with HIV. Although abdominal pain may have myriad causes both in and outside of the gastrointestinal tract, there are some specific HIV-related diagnoses that must be kept in mind.

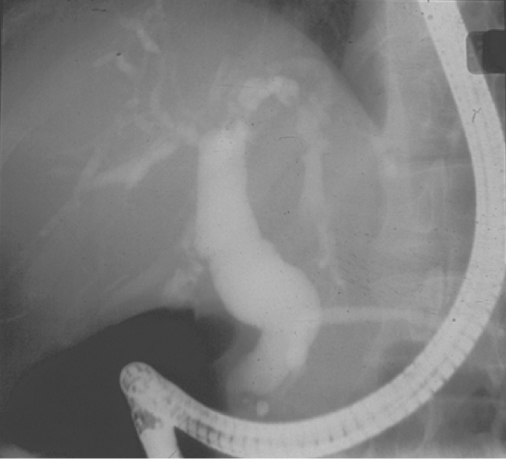

Right upper quadrant pain may be associated with AIDS-related sclerosing cholangitis (Figure 10.11). This condition is pathologically and radiologically identical to idiopathic sclerosing cholangitis with irregular dilatation and narrowing of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts caused by areas of fibrosis. The condition occurs predominantly in those with a CD4 count less than 100 cells/µL. Virtually all cases of AIDS-related sclerosing cholangitis are associated with microsporidium, cryptosporidium or cytomegalovirus infection, and diarrhoea is thus a common accompaniment. Very severe pain is associated with papillary stenosis. As cART is associated with the eradication of the opportunistic infections leading to this condition, it is now rare. Acute acalculous cholecystitis may be commoner than in the general population especially in late stage HIV infection.

Figure 10.11 AIDS-related sclerosing cholangitis:ERCP image shows typical beaded appearance of the intra- and extrahepatic ducts.

Appendicitis may be commoner in HIV-positive patients, probably due to an association with cytomegalovirus infection.

Acute pancreatitis may be associated with infections including cytomegalovirus. The commonest cause however is antiviral therapy particularly didanosine. Severe hypertriglyceridaemia associated with cART may also be an associated causative factor.

The commonest cause for generalized abdominal pain is severe constipation associated with opiate use. Cytomegalovirus infection may present with severe abdominal pain and rebound tenderness and diarrhoea. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI) classically presents with severe abdominal pain, a raised alkaline phosphatase, anaemia and fever. The abdominal pain is sometimes associated with massive enlargement of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes. Treatment with corticosteroids may produce short-term palliation of the pain and specific anti-MAI therapy should be introduced, although the development of resistance is common. Successful cART treatment is associated with eradication of the organism. Lymph node enlargement secondary to lymphoma may also present in this way.

Anal pain may be secondary to infection from herpes simplex infection or in those with a low CD4 count CMV infection. Other sexually acquired conditions particularly Lymphogranuloma venereum may present with perianal pain commonly associated with a bloody mucus discharge. Perianal abscesses and fissures are relatively common. Carcinoma of the anus (see Figure 7.11) occurs more commonly in men who have sex with men and the HIV population in general.

British HIV Association. Guidelines Writing Group on Opportunistic Infection. HIV Med 2011;12(Suppl 2):1468–1293.

Nelson MR, Shanson DC, Hawkins DA, Gazzard BG. Salmonella, Campylobacter and Shigella in HIV-seropositive patients. AIDS 1992;6:1495–1498.

Ng SC, Gazzard B. Advances in sexually transmitted infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:592–607.

Shacklett BL, Anton PA. HIV Infection and gut mucosal immune function: updates on pathogenesis with implications for management and intervention. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2010;12:19–27.