Figure 14.1 Seborrhoeic dermatitis. Erythema with greasy scale on the forehead.

Chapter 14

The Skin and HIV

Overview

Skin disorders are very common in HIV patients

Severity of skin disease increases with decreasing CD4 counts

Cutaneous presentations are often atypical

Have a low threshold for taking a skin biopsy

Management of skin diseases is often difficult, but combination antiretroviral therapy usually helps

The skin acts as a window to underlying systemic diseases including HIV and AIDS. The visual nature of cutaneous disorders means they often act as the initial warning sign of impaired immunity. In general, the incidence and severity of skin diseases in HIV patients is inversely proportional to their CD4 count. Common dermatoses such as psoriasis, eczema and acne can present denovo in the context of HIV and are often resistant to simple therapies. Managing recalcitrant skin disease in HIV patients over the past decade has been transformed by the advent of cART; however, 70% of patients still suffer from HIV-related skin problems with a high incidence of drug rashes and challenging immune reconstitution syndrome. Physicians should have a low threshold for performing a skin biopsy in HIV patients with skin disease as opportunistic infections (CMV, coccidioidomycosis), rare diseases and atypical presentations of common conditions manifest.

An immunological shift in the host–commensal relationship is thought to trigger an eczematous reaction to the yeast Malassezia furfur on the skin. Seborrhoeic dermatitis (SD) affects approximately 1–3% of the general population compared with 50% of HIV-positive patients. Immune dysregulation caused by HIV itself it thought to contribute to the high incidence, particularly in individuals with CD4 counts <100 cells/µL. Classically SD affects the scalp (Figure 14.1), eyebrows/moustache, nasal creases and anterior chest. The eruption is usually asymptomatic. SD is diagnosed on clinical features; however, large numbers of Malassezia yeast can be visualized on microscopy from scrapings. Adherent scalp scale can be lifted by an application of emollient overnight. Twice weekly ketoconazole shampoo to affected skin/scalp can help prevent the scaly eczematous reaction. A combination of hydrocortisone 1% with miconazole nitrate used twice daily is usually effective at relieving the eczema; however, SD is a chronic disease that recurs. Very severe cases of SD in the context of HIV infection can be treated with systemic imidazoles, but complete resolution may only occur following the initiation of cART.

Figure 14.1 Seborrhoeic dermatitis. Erythema with greasy scale on the forehead.

Human herpesvirus type 8 is associated with the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). In the context of HIV cutaneous KS lesions usually affects the face, oral cavity and perineum. Early lesions may be erythematous-violaceous patches or papules that progress to firm plaques, nodules (Figure 14.2) and eventually ulcers with a purplish-brown discoloration. Lesions can occur at sites of trauma (koebnerize), and secondary lymphoedema may occur. Mucocutaneous KS should be confirmed histologically. Radiological imaging may be required to look for systemic involvement. Cutaneous therapy is aimed at controlling bleeding, functionality, cosmetically disturbing and bulky disease. A variety of measures can be considered such as excision, radiotherapy, pulsed-dye laser and intralesional chemotherapy (vinblastine, vincristine and bleomycin).

Figure 14.2 Kaposi sarcoma. Purplish-red firm nodules.

An intensely pruritic follicular eruption of unknown cause that typically manifests when CD4 counts <250 cells/µL. Multiple discrete, erythematous, perifollicular, papules and pustules affect the face and trunk (Figure 14.3). Differential diagnoses include Staphylococcus or Pityrosporum folliculitis and acne. Microbiological swabs are negative. Peripheral eosinophilia and raised immunoglobulin E may be seen. Skin biopsy shows characteristic perifollicular mast cells and degranulating eosinophils. cART is an effective treatment when CD4 counts rise >250 cells/µL. UV-B phototherapy can be effective, as are moderately potent topical corticosteroids and permethrin. Systemic indomethacin, minocycline and itraconazole have been used successfully.

Figure 14.3 Eosinophilic folliculitis. Papules and pustules around hair follicles on the chest.

Non-specific pruritus is common in HIV patients, 30% developing nodular prurigo, the cause of which is unknown. Lesions start as small red papules on the trunk and limbs which itch intensely and through scratching develop into chronic nodules (Figure 14.4) that are scarred and hyperpigmented. Nodular prurigo can be very persistent and responds poorly to most treatments. Patients should use a regular emollient to combat dryness and itching. Moderately potent topical steroids applied daily under occlusion may flatten lesions and reduce itching. UVB phototherapy, ciclosporin and amitriptyline may be helpful.

Figure 14.4 Nodular prurigo. Multiple excoriated hyperpigmented nodules on the trunk.

The frequency of drug rashes in HIV patients is 10 times higher than in the general population, especially at CD4 counts <200 cells/µL. HIV patients often take multiple medications simultaneously, and HIV itself affects the metabolism of many drugs. The majority of drug rashes occur 7–20 days after commencement of the offending drug, and take the form of toxic erythema, which is usually mild and resolves when the medication is stopped. Emtricitabine (FTC) is one of the most widely prescribed anti-HIV medications. It has been reported to cause skin pigmentation (SP), the incidence of which varies with ethnicity, with a higher rate in African-American patients (8%). Zidovudine is also associated with pigmentation of nails/tongue/skin. Use of abacavir may lead to the development of a hypersensitivity reaction, which usually appears within the first 6 weeks. This usually presents as diffuse erythema alongside systemic symptoms. The HLA-B*5701 allele is associated with a significantly increased risk of a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir and pre-screening is recommended. Other drug rashes in HIV patients include mucosal ulceration (zalcitabine, foscarnet), phototoxic rashes (St John's Wort) (Figure 14.5), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (cotrimoxazole, nevirapine and efavirenz) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (nevirapine, abacavir, cotrimoxazole). TEN is 1000 times more common in HIV-positive individuals, and is characterized by painful, rapid, widespread (>30% of skin surface area) full thickness skin necrosis (Figure 14.5) associated with a 25–30% risk of mortality.

Figure 14.5 Drug rashes. Photosensitive eruption on the chest due to St. John's Wort, widespread skin sloughing secondary to toxic epidermal necrolysis due to nevirapine.

Approximately 20–30% of HIV patients are affected by HPV infections. Mucosal infections may be latent (DNA detection), subclinical (detected by 3–5% acetic acid application) or clinical. Cutaneous lesions are readily apparent, often multiple, clustered, widespread and occasionally profuse (Figure 14.6). Multiple plane warts may be seen as a marker of occult HIV disease. Anogenital disease (condylomata acuminata) is characterized by exophytic verrucous lesions that may become cancerous. Deep plantar warts can be painful and usually contain ‘black specks’ which are thrombosed capillaries. Skin warts have a heterogeneous appearance including hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, small plaques, filiform and mosaic lesions.

Figure 14.6 Human papilloma viral warts on the foot. Discrete hyperkeratotic nodules with a rough, filiform surface.

The diagnosis is clinical; however, cytology and DNA subtyping may be helpful. Cutaneous warts are moderately resistant to treatment in the context of HIV. However, salicylic and lactic acid can be effective at high concentrations if used regularly. A course of cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) can be efficacious but may be painful, and transient blistering can result. Curettage and cautery may be performed but causes scarring and there is a risk of recurrence. Immunotherapies such as imiquimod and diphencyprone can be used, but the results are often disappointing.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by pox virus, commonly seen in HIV patients particularly in the beard area (Figure 14.7). The lesions are usually flesh-coloured papules with umbilicated centres; however, atypical forms are also reported. Hundreds of small mollusca are often present and occasionally very large lesions arise (giant mollusca). Molluscum lesions tend to persist in HIV patients, resulting in significant cosmetic embarrassment. The diagnosis is usually a clinical one; however, a smear from the central keratotic plug or skin biopsy reveals multiple characteristic molluscum inclusion bodies. Initiation of cART can cause mollusca lesions to undergo spontaneous regression or paradoxically worsen initially. Persistent lesions can be treated with cryotherapy (10–15 seconds per mollusca) or cautery after topical anaesthesia (EMLA). Giant lesions may only respond to curettage. Topical imiquimod 5% or cidofovir may be effective for resistant lesions.

Figure 14.7 Molluscum contagiosum in the beard area. Multiple coalescing umbilicated shiny papules.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2 commonly cause infections in HIV patients, with 60–80% of patients co-infected with HSV-2. The frequency and duration of HSV infections rises with CD4 counts <50 cells/µL. Deteriorating ulceration (Figure 14.8) however can occur after the commencement of cART, due to the reconstitution of the patients’ immune system, so-called immune reconstitution syndrome (IRS). Commonly affected sites are the anogenital and perioral regions. Acute lesions are characterized by vesicles which progress to crusted, eroded and eventually ‘punched-out’ ulcerated lesions that may become chronic. Recurrent ulceration may lead to giant ulcers (10–20 cm). HSV isolation by cell culture, electron microscopy or immunofluorescence studies on lesional fluid taken by scrapings or swabs. Polymerase chain reaction availability is increasing and is a rapid, highly reproducible, method of HSV detection. Aciclovir treatment is given for localized HSV infections; the dose in HIV patients is usually 400 mg five times a day for 5–10 days. If aciclovir is ineffective, consider resistant HSV (absent viral thymidine kinase) and change to foscarnet 40 mg/kg iv tds, or vidarabine 15 mg/kg iv daily. Valacyclovir has been shown to be superior to famciclovir in the suppression of HSV-2 reactivation.

Figure 14.8 Herpes simplex virus. Extensive genital ulceration associated with immune reconstitution syndrome.

Candida yeast infections have a predilection for mucous membranes and warm moist skin flexures. Oral candidiasis (thrush) classically presents with white plaques on a background of inflammation, but in chronic infections there may be persistent glossitis and cobblestone mucosae. Oropharyngeal infections may spread locally to the oesophagus in HIV patients. Flexural Candida is characterized by erythema with peripheral satellite lesions (Figure 14.9). Swabs for microscopy and culture may isolate the yeast. Superficial Candida infections can be treated with topical antifungals including clotrimazole, miconazole and nystatin in several formulations including lozenges, oral gel, pessaries, and creams. Refractory disease requires systemic therapy with fluconazole 100 mg or itraconazole 200 mg daily for 2 weeks.

Figure 14.9 Candida in the axilla. Confluent macerated erythema with peripheral satellite lesions.

Cutaneous fungal infections of the body (corporis), groin (cruris), feet (pedis) and scalp (capitis) are common in immunosuppressed patients, and are often extensive. Lesions are usually itchy. Annular erythematous plaques with a raised scaly edge may be seen (Figure 14.10). Clinical features may be significantly altered by topical steroids (tinea incognito). Mycological scrapings may isolate the fungus. First-line topical treatment is terbinafine 1% cream twice daily for 2–4 weeks; alternatives are miconazole and ketoconazole. Itraconazole 100 mg for 2 weeks is an effective systemic therapy. Fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 2–4 weeks. Terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks is used to treat tinea capitis infections.

Figure 14.10 Tinea cruris. Annular erythematous scaly eruption in the groin.

Sarcoptes scabiei mite infestation is common in HIV patients and is usually transmitted by close personal contact. Intractable itching disturbs sleep. Patients present with itchy papules especially on the flanks, axillae and genitals, occasionally burrows are seen (finger webs, genitals). HIV patients may develop crusted scabies, which is highly contagious, and characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques (Figure 14.11). Secondary skin changes such as eczema and impetigo may occur. Microscopy from a burrow scraping or crust can confirm the presence of mites. Scabies in the context of HIV can be difficult to eradicate. First-line treatment is 5% permethrin cream to all skin surfaces from the neck downwards, left on for 12 hours. The treatment should be repeated after 1 week. All close personal contacts should be treated simultaneously. Bedding, towels and underclothing should be washed. Systemic ivermectin is the preferred treatment for crusted scabies and recalcitrant infestations.

Figure 14.11 Crusted scabies. Confluent crusting and scaling over the chest.

The World Health Organization estimates the number of new cases of syphilis worldwide each year to be around 12 million. Co-infection of syphilis with HIV in the USA and Europe is reported to be between 20% and 70%. The presentation of syphilis in HIV patients may be atypical, but classically a painless genital ulcer develops 3–4 weeks after transmission. Secondary syphilis presents with a rash, fever, arthralgia and lymphadenopathy 4–8 weeks after the primary infection. The rash characteristically affects the trunk, palms and soles (Figure 14.12) and is non-pruritic. Early lesions are usually annular erythematous macules that fade to a greyish-brown. Serological testing for syphilis should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Primary/secondary syphilis should be treated with a single dose of i.m. benzathine penicillin 2.4 mega units, or i.m. procaine penicillin 600 000 units daily for 10 days. Latent syphilis requires longer treatment.

Figure 14.12 Secondary syphilis. Reddish-brown macules on the sole of the foot.

These opportunistic fungal infections usually affect HIV patients with a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/µL. Patients infected with Penicillium marneffei are usually unwell with non-specific fever, lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, two-thirds of patients have multiple umbilicated papules and nodules on their skin that mimic molluscum contagiosum. Skin biopsy for histology and culture is diagnostic in 90% of cases. Only 10% of patients infected with Cryptococcus neoformans develop skin lesions; these are similar to the umbilicated nodules seen in Penicillium infections; however, ulcers and/or pinpoint haemorrhages (petechiae) may also occur. Histoplasma capsulatum infections are mainly characterized by respiratory disease. Skin lesions may manifest as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme; however, with dissemination multiple pustules and nodules can appear on the skin containing the fungus.

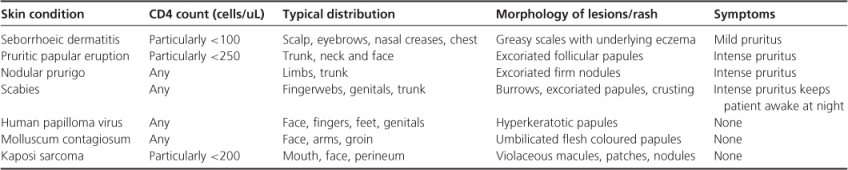

Skin conditions in HIV-infected populations are common and varied. In order to confirm the diagnosis a number of tests could be performed, including syphilis serology, skin scraping and viral PCR. Skin biopsy is an important tool in the armament of a clinician attempting to diagnose a dermatological condition (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 Common dermatological manifestations of HIV infection.

Eisman S. Pruritic popular eruption in HIV. Dermatol Clin 2006;24:449–457.

Gottschalk GM. Paediatric HIV/AIDS and the skin: an update. Dermatol Clin 2006;24:531–536.

Hogan MT. Cutaneous infections associated with HIV/AIDS. Dermatol Clin 2006;24:473–495.

Honda KS. HIV and skin cancer. Dermatol Clin 2006;24:521–530.

Martins CR. Cutaneous drug reactions associated with newer antiretroviral agents. J Drugs Dermatol 2006;5:976–982.