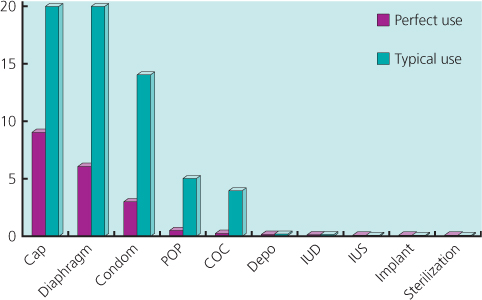

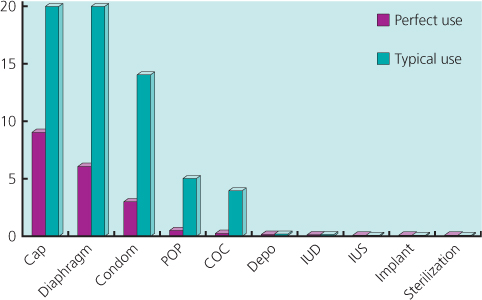

Figure 17.1 Contraceptive failure rates (%) in first year of use demonstrating the difference between methods and perfect and typical use. Adapted from the CG-30 Clinical Guideline on Long Acting Contraception. NICE 2005.

Chapter 17

Women and HIV

Overview

The natural history and overall management of HIV in women does not differ significantly from that in men

For optimum outcome of a pregnancy in an HIV-positive mother, an experienced multidisciplinary team should be involved from diagnosis

With correct management almost all mother-to-child transmission of HIV can be prevented

No method of contraception is contraindicated solely on the basis of a woman being HIV infected, with the exception of vaginal barriers used with spermicide

The most effective method of emergency contraception is a copper intrauterine device

The efficacy of many forms of contraception (including emergency contraception) can be affected by combination antiretroviral therapy

Sperm washing and artificial insemination are examples of interventions that can help minimize transmission of HIV in discordant couples who are trying to conceive

The diagnosis of HIV infection may be devastating for any individual and lead to anxiety, depression and stress; however, there may be additional considerations for newly diagnosed women who may have to consider the possible HIV-positive status of any children and the implications for future pregnancies. Women may fear, or actually experience, violence from their partner on disclosure of their status. As carers some women may find it difficult to prioritize their own health needs.

The natural history of HIV infection is not significantly different between men and women when the mode of acquisition of HIV is controlled for. A similar spectrum of opportunistic infection and malignancy is seen, and guidelines for antiretroviral treatment suggest using similar CD4 cut offs for deciding when to start therapy. The same antiretroviral drugs are used, except that women at risk of, or planning, a pregnancy should avoid the use of potential teratogens. Response to therapy does not appear to differ significantly between men and women.

As policy in much of the developed world including the UK is to recommend an HIV test as part of all women's antenatal care, and as women with diagnosed HIV are now remaining well for longer, more women with HIV are being managed in pregnancy. For women who are first diagnosed HIV-positive during pregnancy, it is important to recognize that this may present complex issues for the patient regarding disclosure of her status to partner and family. Help with multiple psychosocial issues such as adjustment to the diagnosis, immigration and housing may be required. The issue of testing other children as well as her partner must also be addressed.

There is a small risk that some women may acquire HIV during pregnancy. Consideration should be given to repeat HIV testing in women who may be at higher risk of HIV acquisition and those who present with typical HIV seroconversion-like symptoms. National guidance (BHIVA, 2008) also recommends near patient bedside testing for HIV for untested women in labour.

For women with diagnosed HIV infection who plan to become pregnant, it is important to optimize their HIV treatment and review the need for any regular medication they may be taking. An STI screen is advised and should be repeated during the pregnancy.

The management of HIV-positive pregnant women should be undertaken by a multidisciplinary team to include, as a minimum, a specialist midwife, an HIV specialist, an obstetrician and a paediatrician, but others may need to be involved (Box 17.1). The health of a woman who is well at the outset of pregnancy is probably not compromised by an uncomplicated pregnancy and the likelihood of an adverse pregnancy outcome is only slightly greater than in the general population, with the possible exception of a greater risk of early preterm delivery.

Without intervention, a breastfeeding mother has a 20–30% risk of transmission of HIV to her baby. This can be reduced to approximately 1% by the use of antiretrovirals, avoidance of breastfeeding and caesarean section in certain situations. For women who are not on therapy and who do not require therapy for their own health they may choose between

A resistance assay is recommended before treatment is started and should be repeated after treatment is discontinued.

Women who require treatment for their own health should be treated with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), starting as soon as practicable. Reports to date do not suggest any excess of fetal abnormalities in babies exposed to antiretrovirals in utero, with the possible exception of didanosine. Up-to-date information about pregnancy outcomes is available through the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Register (www.apregistry.com). Maternal toxicity from antiretroviral drugs is well recognized and advice should be sought from an experienced HIV clinician before commencing therapy in pregnancy. British and European guidelines on the management of HIV infection in pregnancy are regularly updated and available online for up to date advice on specific HIV therapies.

Women who conceive while taking combination therapy should continue this if it is well tolerated and achieving an undetectable viral load. No antiretroviral medications are licensed for use in the first trimester. The unknown long and short term effects of conceiving on cART should be discussed. Where therapy is failing, the woman presents late in pregnancy or presents with threatened premature delivery, specialist advice should be sought.

Studies showing that an elective caesarean section reduces the risk of transmission from mother to child were conducted before the routine use of cART so the additional benefit of caesarean section in these women is not known. Women who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load on combination therapy may elect to have a vaginal delivery.

All babies born to HIV-positive women should be given 4 weeks of antiretroviral treatment, usually with a monotherapy component of the maternal treatment. Combination treatment may be required where the baby was delivered to a mother on combination therapy with a detectable viral load, suggesting poor adherence or resistance and for babies whose mothers received no cART.

All babies should be formula fed to reduce the risk of HIV transmission associated with breastfeeding.

Parents should be advised that the HIV status of their baby can be confirmed by PCR testing by 3 months of age. Follow-up for all infants exposed to antiretrovirals in utero or born to an HIV-positive mother should be arranged.

It is not possible to generalize care guidelines to the whole of the developing world as access to components of optimal therapy vary greatly. However, all women should have access to HIV testing during pregnancy, with the option of at least short course cART to minimize HIV transmission to their babies. Recent data from Botswana (www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0907736) has shown that the risk of HIV transmission to babies in women who initiate cART during pregnancy and continue throughout breastfeeding is 1.1%. Avoidance of breastfeeding is not possible unless access to safe and sustainable supplies of formula feed can be arranged, and even then bottle feeding may not be acceptable because of the implied HIV-positive status. Owing to these considerations the World Health Organization recommends that HIV-positive mothers or their infants take antiretrovirals while breastfeeding to prevent HIV transmission.

For the most part, the gynaecological care of women with HIV is similar to that provided to women without HIV/AIDS, the main exceptions being in relation to fertility treatment, cervical cancer prevention and genital infections such as human papilloma virus (HPV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Candida, which are more likely to be recurrent or severe.

HIV infection increases the risk of both cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and appears to be associated with immunosuppression. CIN is present in between 20% and 40% of women with HIV.

All women newly diagnosed with HIV and who are aged 25 years or over should have cervical screening if not performed within the last 12 months. Some recommend baseline colposcopy due to the prevalence of false-negative smear results, but this is dependent on resources. Thereafter, annual cytology should be performed with referral for colposcopy based on UK national guidelines. High-grade CIN (2 and 3) should be managed according to national guidelines. However, recurrences are common, reportedly being as high as 80% in women with CD4 counts below 200 cells/µL. Low-grade lesions should not usually be treated as they probably represent persistence of HPV infection, which responds poorly to treatment. Regular cytological monitoring is mandatory.

cART appears to increase the regression of low-grade lesions. However, the effect on high-grade lesions and HPV persistence is less clear and women on cART should be managed as other HIV-positive women.

Women with HIV may experience genital infections such as herpes simplex, candidiasis or warts that are more severe, recurrent or persistent than in women without HIV infection. For the most part the treatment regimens are unaltered, but prophylactic or specialist referral may be required (Table 17.1).

Table 17.1 Treatment regimens.

| Treatment or persistence | ||

| Diagnosis | Single episode treatment | or frequent recurrence |

| Herpes simplex |

5–7 days duration, may be extended in severe infections

|

If recurrences frequent and episodic oral treatment may be prescribed to be initiated by the patient early in a recurrence Prophylaxis (at least 6 episodes per annum) Aciclovir 400 mg 2 × day. Discontinued after 1 year to assess recurrences, but good data on long-term safety |

| Genital candidiasis | Topical or systemic anti-fungal agents (e.g. clotrimazole, fluconazole) | Systemic antifungals (oral imidazoles) are sometimes used long term to prevent recurrence. |

| Genital warts | Topical therapy (podophyllotoxin or imiquimod) or cryotherapy | Refer if not responding to treatment |

Women requesting contraception, including those with HIV, should be supported to make an informed choice of the most effective method that is acceptable to them (Box 17.2). The role of healthcare providers is to ensure safe choice and support effective use. Efficacy between methods varies. Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) (Figure 17.1) are the most effective reversible methods (Table 17.2), and are comparable to permanent methods such as female and male sterilization; however, the latter is the most effective method.

Figure 17.1 Contraceptive failure rates (%) in first year of use demonstrating the difference between methods and perfect and typical use. Adapted from the CG-30 Clinical Guideline on Long Acting Contraception. NICE 2005.

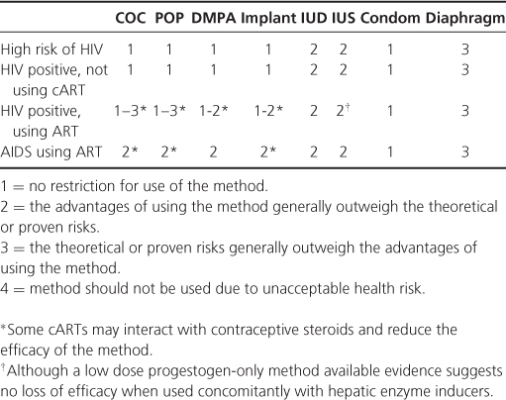

Table 17.2 UK contraceptive medical eligibility criteria for women with HIV.

With the exception of vaginal barriers (caps and diaphragms), which require nonoxynol-9 use, all methods are suitable for most women. The UKMEC (Table 17.2) provides basic guidance on the use of contraception with medical conditions. Care is needed in the UKMEC in women with multiple conditions. Depo-Provera (DMPA) has been associated with reduced bone mineral density (BMD), although not osteoporosis and fracture; caution should be exercised in women at risk of reduced BMD and other methods considered. Drug interactions are important; hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs, including some cART, are likely to reduce the efficacy of combined oral contraceptives (COCs), progestogen only pill (POP) and implants and should not be used without condoms and after considering all other methods. DMPA (Depo-Provers), IUS (intrauterine system) and IUD (intrauterine device) are not known to be affected by liver enzyme inducers. Consistent condom use should be encouraged in conjunction with other methods.

Women should be advised of the indications for emergency contraception (EC) and how to access it. A copper IUD is the most effective method and can be used within 5 days of intercourse, and importantly depending on the menstrual history often beyond this. Progestogen-only emergency contraception (POEC) containing levonorgestrel is available without prescription in the UK or from a healthcare provider and is best used as early as possible within 72 hours of intercourse. A new prescription-only oral emergency contraceptive, ulipristal acetate (UA), a selective progesterone receptor modulator, is now licensed for use up to 120 hours after intercourse in the UK. Available evidence suggests that this is more effective than POEC, but it can be used only once in a cycle, and because of its mechanism of action may reduce the efficacy of hormonal contraceptives started immediately after taking UA. Women on hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should consider an IUD or double the dose of POEC, which is off-licence and of unknown efficacy, there is no guidance on the use of UA in these patients. The use of UA is not recommended in women using medication that increases gastric pH.

Discordant couples without established subfertility require advice to minimize HIV transmission risk. Sperm washing is the treatment of choice where the man is HIV positive and should carry no risk of transmission. However, for some couples timed unprotected intercourse may be the only accessible treatment, which carries a risk of transmission. HIV-positive women can use self-insemination and should be provided with information on doing this. For those with established subfertility many investigations can be carried out in primary care but those requiring assisted conception should be referred to a specialist unit experienced at providing care for couples with HIV.

BASHH. Guidelines on Diagnosis and Management of STI. (www.bashh.org).

BHIVA. Guidelines for the Management of HIV Infection in Pregnant Women and the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. (www.bhiva.org).

EACS (www.europeanaidsclinicalsociety.org/guidelinespdf/EAEuroGuidelines_FullVersion.pdf).

FSRH. Guidelines on use of contraceptive methods, including emergency contraception are available from www.fsrh.org.

NICE. Clinical guideline on Long Acting Reversible Methods of Contraception. 2005 (www.nice.org.uk).

UK Selected Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use (2009). FSRH. www.fsrh.org Management of sexual and reproductive health of people living with HIV infection (2007). BHIVA, FFPRHC, BASHH. 2007 www.bhiva.org.