Lo Splendore della Luce a Bologna

Collages by Roy R. Behrens

I

The locomotive bringing a trainload of philosophers to Bologna hissed and ground to a standstill in the long Apennine dusk to have its headlamps lit and to be dressed in the standards of the city and the university. On both sides of the smokestack and at the four corners of the tender the red flag of the Partito bravely rode.

With dying drivers and rolling bell, victorious whistle and a glory of steam, they slid into the march from Aida played by the Filarmonica Municipale deployed along the platform in front of the guard of the Podestà who saluted the philosophers with swords at port arms in the first rank, with gonfalone in the second.

—Viva la filosofia! cried the crowd.

—Portabagagli!

—La bandiera rossa trionferà!

—È vergine la mia sorella!

—Benvenuto, stregoni!

—A chi piace una banana?

—Alle barricate!

—Sempre Marconi!

—Carrozze!

—Viva la filosofia!

Kissed on both cheeks by a sashed, whiskered, top-hatted academic as he descended from the train, Mr. Hulme took his seat in a carriage with Henri Bergson, Murray of the London Aristotelian Society, and F. C. S. Schiller the Oxford pragmatist, and rode down the Via Aemilia in a torchlight procession.

II

In the morning, sipping coffee, Mr. Hulme could find no proportion in the arcades, the buildings, the windows, the campanile, the duomi, the typography of the newspaper, that was not perfect. The children and the old people made him sad. All ideas rise like music from the physical.

III

Tomatoes, baroque and crimson. A hobnail-booted priest taking snuff. A cricket on a freckled pear. The way these Bolognese women pick up figs at the greengrocer’s, discuss them, judge them, praise them, is not English. Kensington housewives would say figs! and ever so dear. How they sort through them here, nibble them, twirl them, choose a clutch, and gabble a minor oration about them.

IV

Cinders and ashes, the world, except where we have made a garden, a kitchen, a shrine, a wine press. In all his life there would be but three moments when the tough opacity of the world became transparent so that he could see the fingers of God at work: on the prairies of western Canada, in the splendor of the light at Bologna, in the trenches of Belgium.

V

Gypsies with black teeth. Boys leapfrogging down the arcades. A nun with two flasks of wine. Punchinello strutting to a drum. Polizia in leather hats with cockades. Caricature, he knew, began here: Annibale Carracci. Two boys peed in a gutter. Bells clanged, chimed, charmed. Bologna smelled of horses, garlic, wine, a sweet rot as of hay, apples, or onions in ferment.

Drum roll and trumpets: the philosophers are going to the convocation.

VI

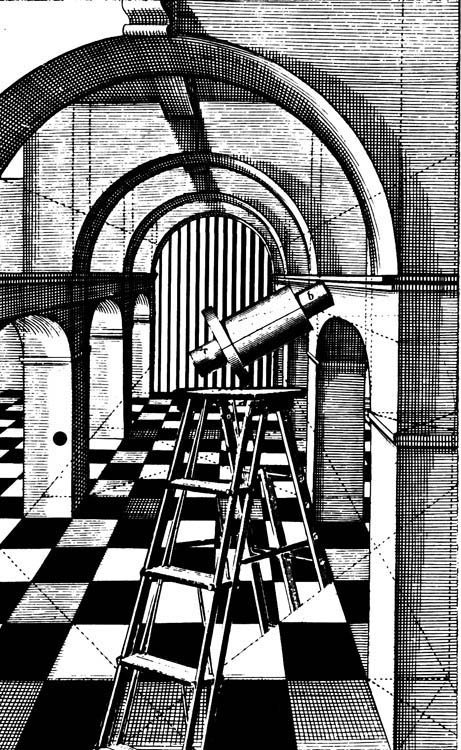

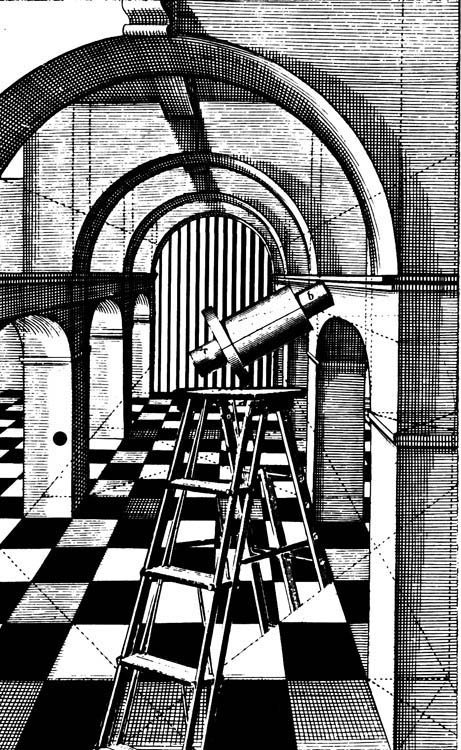

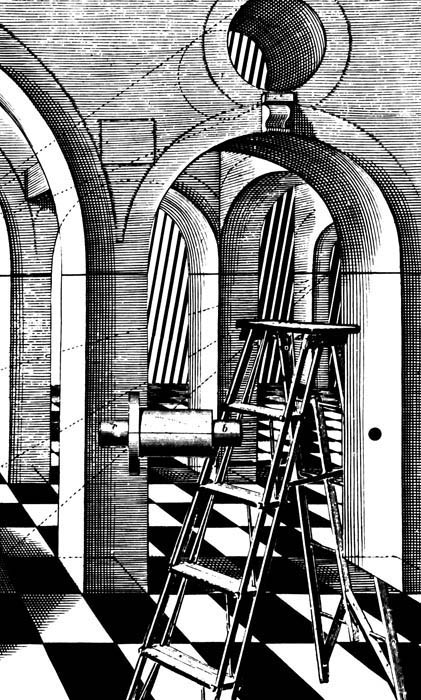

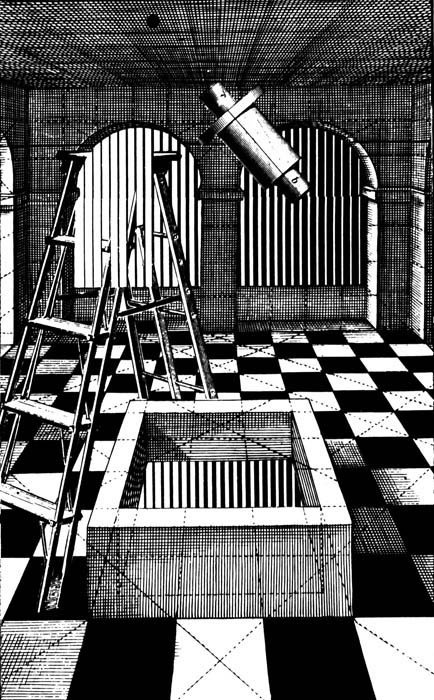

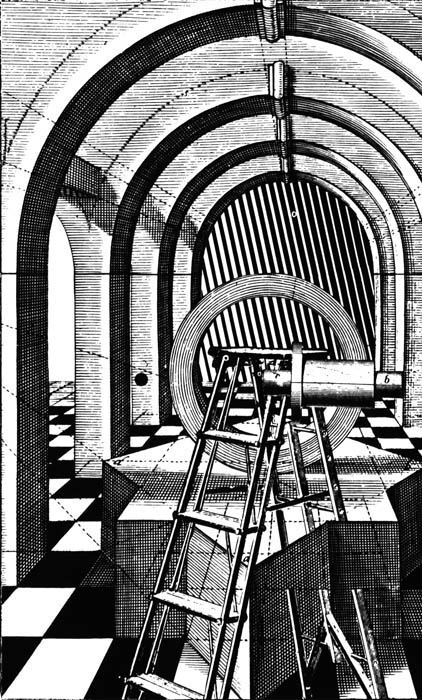

In 1603, at Monte Paderno, outside Bologna, an alchemist (by day a cobbler) named Vicenzo Cascariolo discovered the Philosopher’s Stone, catalyst in the transformation of base metals into gold, focus of the imagination, talisman for abstruse thought. Silver in some lights, white in others, it glowed blue in darkness, awesome to behold.

VII

At the Fourth International Congress of Philosophy, convened in Bologna the first week of April 1911, Mr. T. E. Hulme, registered through scribal error as F. E. Hulme, delegate from the Aristotelian Society of London, La Gran Bretagna, undertook to exercise the dictum that Henri Bergson passed on to him from the man he called William Jones, namely that one look at a philosopher is enough to convince you that there you need trouble no further.

Did he believe with Aristotle, Lavater, and Lombroso that the supposed rattiness, horsiness, or other animality of a face designated a ferality of the soul? Bergson? Surely he meant something else, something quite else.

William Jones, assuming him to be, as we safely may, the same as William James, had died the preceding August in the mountains of New Hampshire, surrounded by his wife, his children, and his brother Henry. He was to have read a paper on Naturphilosophie at the Congress.

—A loss, Ernst Mach said, a distinct deprivation. He went up the Amazons with the great Agassiz, you know, and at Harward he was successively professor of medicine, psychology, and philosophy. At my table in Vienna he was a brilliant talker, in good German, on any subject, mechanics, disease, bicycles, madness, religion, politics, fashion, Puccini, frogs, engineering. Ach, he would put the tablecloth around his throat without the least diminishment of his dignity and give an imitation of the creole philosopher Georg Santajana, an Epicurus among the Jansenists at the Collegium Harward.

Hulme tried to imagine Aristotle doing Plato, fluttering his hand, pushing his fingers through his beard.

—All my children laugh, they could not but, and even my dear wife, helplessly, permit herself the giggle, it was entirely appropriate. And then this marvellous Herr Professor James would be talking about disjunct personalities in the madhouse, people with two or more different identities, and about his visit to Paris to see the spastic writer Fräulein Stein who was a student of his at Harward, and how in England he climbed a ladder and looked over his brother Henry’s garden wall to see some writer of the English who lived next door, H. G. Wells I think it was, or perhaps Jerome Jerome, and how his brother, who has become more correct than the English, was scandalized, and so were we, but vastly amused, you understand. It is a mark of a sensibility enlarged by imagination to have the overpowering curiosity, like a child not yet fully disciplined, to climb a ladder and look over a garden wall. It is something Goethe would have done, in Italy.

—And here we are, in Italy ourselves, Mr. Hulme replied in his best German.

—Ganz recht! exclaimed Herr Mach, rolling his wine in his glass. And over whose garden wall should we gaze? Ha ha.

VIII

Images will sharpen, dialectic will assert itself, sculpture will become abstract, painting will return to clear color and geometric line, manners will grow natural and frank, life will be convenient, healthy, sweet. But the morbid, the frenetic, the humbug must go away. Romanticism must die, or daydreaming will drown us all in a great muck.

Against the caress of the smooth put the abrasion of the rough.

Trace every shadow back to the light that caused it. Cherish the light, respect the shadow.

The Bolognese women seemed to be out of the Bible, shawled, competent, chaste, and severe, or out of Goya, trivial, vain, and with a duchess complex.

IX

Samuel Alexander looked like God. Bergson was an elegant cat, privy to the mind of Montaigne. Hüsserl, a chemist who played in a string quartet. A philosopher might well study the human face, like Rembrandt or da Vinci, so long as he kept taxonomy and statistics at bay. Each man is a species and cannot be further classified.

X

Cone, sphere, cube.

XI

A boy leading a horse, an old woman who looked like Pestalozzi drinking a wine as black as ink, an adagio of nuns on a bridge, partridges flecked with blood hanging outside a trattoria, melons golden in a basket, an orange and blue poster of an aeroplane pasted beside a board that gave in baroque and gilt lettering the times of the masses at San Procolo, goats with eyes of the Devil wearing long bronze bells that banged as a bass to their bleats, their herdsman talking socialist theory with a tall girl out of the Book of Ruth who was carrying a lute, a baby, a jug, and a parasol with a scarlet fimbria.

When there shall be no more the slot of oxen in the road past the cathedral, nor ring of sparrows gleaning with the poultry at the mill, nor shoal of sheep by the doors of merchants, then will civilization find itself more a mistake than an advantage.

XII

A discussion over whiskey and figs at the Caffé Garibaldi. Whether phenomenology be idealistic or pragmatic, whether psychoanalysis might contribute to the solution of the problem of other minds.

A troop of cavalry cantered by jingling, red-coated, white-gloved, Mexican of moustache, Greek of eye, rout step, talking of women.

Philosophy in England?

—O, replied Mr. Hulme, it is a little circle of physicists around a New Zealander at Manchester named Rutherford, some mathematicians at Cambridge, a Jew from America, one Epstein, and a young Frenchman, Henri Gaudier, both sculptors, and two Americans, Percy Lewis, a painter, and Ezra Pound, a poet.

Was Signore Ulmo of a seriousness, or did he, in the idiom, draw the leg?

—Never the leg! roared Hulme. Never the leg.

XIII

Across a stage in Paris, impersonating the puppet Petrushka, Vaslav Fomich Nijinsky hopped on his toes, jiggled his eyes, bounced like a jumping jack, went limp like a doll, sprang up as if shot from a bow, heel circling heel, the silliest of bumpkin’s smiles on his carnival face. Hulme and Gaudier would see him in a few months as a faun with a leopard’s balance dreaming in a liquid trance.

XIV

To realize, with precision, a feeling in all its fullness. With accuracy of tone. To be in the world is fate, to be aware of the world is, if our minds are analytical, philosophy, if our minds are synthetic, art.

What, it was asked of Monsieur Eulme, would be the philosophy of the twentieth century be, in his opinion, en effet.

—Great learning accompanied by squalid ignorance, sophistication vitiated by simplemindedness. Romanticism just might, if the worst happened, amplify fanaticism into hysteria. Classicism, that is, the rational life, had some chance of a renaissance: in the passion of the Mediterranean peoples, in the cold clarities of the French, in the formal intelligence of the Chinese.

—But it is not likely.

—Perchè non?

—Original sin. Rascals in power. The triviality of city life. Machines and turbines. Vulgarity.

XV

In the yellow and brown geometry of Bologna stood a figure, a man in a bowler hat. Perspective, with citizen. Hulme approached him with jolly English strides, perfuming the air with his pipe. He had thought, from a distance, that the man was Bergson, but as he drew nearer he saw that he wasn’t. One of those Spanish blokes, was he? They fancied dark clothes, too, and were apt to wander off into the streets by themselves, to be shouted at by Italian voices inside dark rooms, from balconies, from behind walls. Or the voices would caution children not to look at the philosophers, who were sure to have the evil eye.

—I say, said Hulme, by way of greeting. Buon giorno, don’t you know, what?

It surprised him that he spoke at all, but he was on the blighter before he knew it. Italy made one expansive, outgoing, decidedly un-British.

Something, no doubt, to do with the light. The splendid light.

—Hulme, he said. Here for the philosophical conference.

—É successo qualche cosa? Smarrito?

—Quite! beamed Hulme.

—Non ci spadroneggiate!

—The light! Don’t you know, what?

—Andatevene, feccia inglese, per i fatti vostri.

—Astoundingly jolly, said Hulme indicating red roofs, long arcades, mellow light on walls. The continuity of it all.

XVI

On the third day of the conference the philosophers were taken by train to Ravenna where there was a reception for them given by the king.

At Galla Placidia Hulme stared at Byzantine mosaics, golden apostles on a ground of blue.

Christ the Shepherd bore a lamb. Christ Pantocrator blessed the world with his hands.

Sant’ Apollinare in Classe Fuori stood in its pine grove, cylinder and rhomb, silo and barn, symbol and function inseparable. Stone and pine, gold and marble. The mosaics gleamed in moving glosses as he moved, a sheen of fire running from big eyes to the flow of beards and long calm hands clasping croziers and books.

The infinite moves both ways, inward, as here, outward, as on the Canadian prairies, radiant without bounds, focussed in a design of sharp lines, concavities, surfaces.

XVII

The full moon rose over the pines like the red face of a jolly farmer above a hedge.