James VI of Scotland, now James I of England as well, had only been married for a few weeks to Anne, the sister of the king of Denmark, and now walls of water were battering the ship. Even the admiral of the Danish fleet escorting the royal couple was amazed by the ferocity of the storm.

‘I’ve never seen the like,’ he said. ‘It’s unnatural.’

King James blanched, knowing what that meant. ‘You mean … witchcraft?’

‘Witchcraft,’ the admiral confirmed grimly. ‘In Denmark we recently executed a coven who raised storms just like this.’

King James VI of Scotland, notorious hater of witches, target of plots, and also James I of England. (North Wind Picture Archive / Alamy)

Only a few miles away, a group of robed and cowled figures stared out to sea from a cliff-top field. Despite the black sea, black sky, and impenetrable sheets of rain and lightning, they all had their eyes fixed on the same distant spot, as if they could see the king’s ship bumping and bouncing on the massive swells.

They chanted as they danced rhythmically, while a central figure in finer scarlet robes dipped a dagger into a goblet filled with thick red fluid. Around him, women with their hoods thrown back stretched their arms up to the skies, their hair flying loose around their heads. The figure in the scarlet robe turned, gathering the winds, and pushed out with his hands as if trying to shove someone off their feet.

At sea, a solid mass of spray slammed into the king’s ship, ripping lines from the sail. Wooden tackle whirled across the deck, breaking bones as the ship lurched.

‘Tack into the wind!’ the Danish admiral shouted.

‘We must make port at Leith,’ the king insisted.

‘We’ll never make it there. We have to turn away and head south.’

‘I am the king!’

‘You are not my king. But your queen is my princess, and I will not endanger her.’

Sullenly, the king fell silent.

On the cliff top, the robed figures lowered their arms.

‘It is over,’ the man in scarlet said. ‘We have failed. The king lives.’

In the little town of Tranent, in North Berwick, David Seaton was waiting for his maid to return. As dawn approached, he heard a window open in the kitchen. A shadowy figure was climbing through, and when he uncovered the lamp he was holding, he saw that it was his maid, Gillis Duncan.

‘Where have you been at this hour?’ he demanded. ‘Selling your healing salves?’

‘No, no … I’ve been …’ She trailed off, unable to think of a good excuse.

‘Did you think I wouldn’t notice? The potions, the midnight walks … I think we’re going to have a little walk into town, Gillis.’

The rest of the family had risen from their beds by now, so she had no choice but to go along with them as they frog-marched her to the jail at Tranent. A soldier met them there.

‘What’s going on here?’

‘I think,’ said Seaton, ‘this woman is a witch.’

It didn’t take long before the king heard about this arrest and had Gillis brought before him. The king looked at her as if she was some new and particularly strange kind of insect. He was obsessed with witches and terrified of them.

‘It will go easier on you,’ he told her, ‘if you tell me who else is in your coven.’

‘I dinna ken anything about any coven …’

‘Then it’s just coincidence that witchcraft from your town raised a storm to try to kill me and my bride?’

‘Aye, I suppose so.’

‘Put her to the torture,’ the king told his men.

A few days later, the bleeding and broken Gillis was brought back.

‘Talk to Agnes Sampson,’ she whispered.

So the king did exactly that. The elderly and well-respected Sampson was arrested and brought to Holyrood House. There, she was chained to the wall by the witch’s bridle, a metal cage for the head with four iron spikes in the mouth. Denied sleep and kept with a noose around her neck, she eventually gave in.

‘Who leads your coven?’ the king demanded of her. ‘Who is your wizard?’

‘The Devil himself,’ Agnes Sampson said. ‘The rightful prince. He told us that the king should be consumed at the request of the earl of Bothwell.’

Soon others gave the same name. A man called Ritchie Graham came forward, confessing to having conspired with Bothwell to raise storms to kill the king.

The king was both horrified and delighted; he was horrified that such evil was so close to the court, but delighted that his enemy proved to be a known political rival. Bothwell was also the admiral of the king’s fleet and so perfectly placed to have known where to raise storms to catch the king’s ship.

‘Arrest the earl of Bothwell,’ he told his guards.

Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, was hurled roughly into a windowless cell in the heart of Edinburgh Castle. Still in his finest doublet, he slammed against the rough stone wall and dropped to the ground.

‘I see James still knows how to be the perfect host,’ he shouted to his guards as they slammed the heavy door closed.

It wasn’t long before the king himself descended into the bowels of the castle to question him through a grille in the door. It was the only opening, apart from a slot near the floor where dinner plates could be pushed through.

‘Cousin …’

‘Don’t call me that, sorcerer,’ the king snapped. ‘You’re no family of mine.’

‘The chancellor is behind this,’ Bothwell insisted. ‘He’s jealous of my position, or fears for his.’

‘That you conspire … well, that’s politics. But witchcraft, Bothwell? That’s an abomination.’

‘This accusation is a greater abomination.’

‘We’ve rounded up all your witches. Those poor souls you’ve tempted, those souls you’ve bought … Aye, they’ll be cleansed in the fire. The repentant will be strangled first, of course. As a mercy. You’re going to burn too.’

‘Am I? Do you think even the most superstitious sheriff will believe the king’s cousin is a wizard?’

‘They will when the king confirms it. In three weeks, I promise you, you’ll be back in hell where you came from.’

Bothwell smiled slowly. ‘And what makes you think I’ll be here in three weeks? If I am a wizard, what sort of cell do you think can hold the Devil prisoner?’

The king hurried away. He wasn’t concerned about whether the authorities would believe Bothwell was a wizard; he had already forced them to convict over a hundred of his subservient witches.

A week later, he returned, talking through the grill in the door again. Bothwell, now in a rather dirty shirt, was still there.

‘The cell seems to be holding you.’

‘Seems.’ Bothwell smiled, despite his imminent trial and execution. The king hurried away.

On the second week, the king returned again. Bothwell, filthy, was unbowed as he came to the grille.

‘Remember, cousin, you’re only king for life.’

‘Longer than you’ll ever live,’ the king promised. ‘Next week, you’ll be tried, sentenced, and executed.’

‘How do you execute the Devil?’ Bothwell asked. The king ran out of the dungeon.

Three weeks after Bothwell had been thrown into the cell, the king led a troop of his most elite guards to escort his sorcerer cousin to his fate personally.

‘Open the door,’ he ordered, giving the jailer the key.

The jailer hurriedly opened the door to the windowless cell for the first time since Bothwell had been incarcerated. It was empty.

‘But …’ the jailer paled. ‘He was there last night; he had his dinner …’

All the king could hear was the faintest echo of his cousin’s mocking laughter.

That Christmas, the king was enjoying a feast in his private chambers when he heard a familiar voice.

‘I told you a prison couldn’t hold a wizard.’

The king turned to see Bothwell standing in a corner, his hand on his sword. He was dressed as finely as he ever was.

‘Did you come to kill me?’

‘Maybe. Or maybe I came to try to get you to see sense.’ He stepped forward.

‘Guards!’ the king screamed.

Immediately the door burst open, and guards flooded in. It was too late, however, since Bothwell was gone, as mysteriously as he had arrived.

Gathering practitioners of the black arts was, oddly, a circumstance under which people from many different classes would work together with the same aims: to raise demons, alter the weather, and hold dubious revels. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

One day a youth neglecting his studies purchased a book on astrology in which he found a diagram that baffled him because the trigonometry required to understand it was not taught at his university. The book led him on an exploration of extant mathematical knowledge, and when he couldn’t find the answer, he invented it. The year was 1664; the place was Stourbridge, near Cambridge, and the student was Isaac Newton.

Exploring God’s world through science was seen as the highest duty of a hermetic or magician. Before Newton, mathematics was based on the Aristotelian and Platonian belief that perfect geometry existed only in the mind of God, and that earthly forms were an imperfect version of this.

The mathematics of circles and degrees of arc were required to understand the Greek model of the fixed heavens as interlocking crystal spheres. Their movement was precisely calculated to mathematical measurements, which translated into musical intervals, the music of the spheres. Geometry was also required in architecture, which was based on the ideal proportions of the human body. Hence the famous diagram of Vitruvian Man, which shows man and architecture reflecting one another, as in Hermes’s central idea of ‘as above, so below’. The value of pi was also thought to be magical because it could not be finitely calculated. The quest to turn lead into gold was expressed in terms of squaring the circle – having a square with the exact surface area as a circle held within its borders.

Before Arab mathematicians revealed it, Europe had no concept of the value 0, so this also attracted much magical significance when it was first introduced. The Chinese created the Lo Shu magic square in 650 BC – predating sudoku by millennia.

4 9 2

3 5 7

8 1 6

Here the lines of figures, horizontal, vertical, and diagonal, all add up to 15 (the number of days in ancient China’s 24-month solar calendar).

Later, the precision of mathematics was transferred into the beliefs and practice of ritual magic in Graeco-Roman times. For example, the Lo Shu square was associated with Saturn, and all the other planets had their own number squares that were used in incantations, which ‘geometers’ would use in the creation of necromantic and other rituals.

In 1590, King James VI of Scotland married Princess Anne of Denmark, and during the return voyage their ships were assailed three times by deadly storms. The Danish authorities had recently had a witch-hunt against supposed witches who raised storms, and so perhaps it was their influence that began what became known as the North Berwick Witch Trials.

Overall, more than 100 people were arrested and 53 were executed. There was an added twist in that, as well as the usual type of suspects from the lower classes, a few respectable nobles, including the king’s own cousin, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, were implicated.

Bothwell and the king were grandsons of James V, and Bothwell was admiral of the king’s fleet, but he was known to be envious of the throne. His father was suspected of having murdered the king’s father, Lord Darnley. In fact, Bothwell’s father, the fourth earl, had been legitimized as successor to the Scottish throne by both the pope and the king’s mother, Queen Mary, who had been forced to abdicate in the king’s favour. Worse still, Bothwell had been arrested only the previous year for conspiring to usurp the king at Holyrood, but his trial had been deferred on account of the family connection.

Even before the trials, it was written that Bothwell ‘had much traffic with witches and was himself an expert necromancer’. That said, the king had so weighted the council of nobles against the accused to ensure convictions that the fact that Bothwell actually got away is pretty unusual. Only one other person was acquitted, a woman named Barbara Napier – at which point King James had the jury found guilty of contempt of court and forced a retrial with the ‘correct’ verdict.

Bothwell was declared an outlaw three days after escaping Edinburgh Castle, the declaration saying he had ‘given himself ower altogidder in the hands of Satan’. He really did come to visit the king in December of 1591, either to kill him or to explain himself.

In 1592, the Scottish Parliament stripped Bothwell of all titles and honours, and in response he brought 300 men to try to capture the king at Falkland Palace by decidedly non-wizardly means. This failed and he was forced to flee, hunted for months. In March of 1593 he mysteriously appeared in the king’s bedroom, accompanied by armed men. This time, however, he had brought them for the theatrical gesture of laying their swords at the king’s feet as a sign of loyalty. Amazingly, the king accepted this and pardoned him.

Bothwell didn’t honour the pardon, however, and soon was engaged in battle with the king’s forces, after which he converted to Roman Catholicism and went into exile, first in France and then Italy. He died in Naples in 1612.

While in exile, Bothwell wrote this letter to a French witchfinder:

You Christians are treacherous and obstinate. When you have any strong desire, you depart from your master and have recourse to me; but when your desire is accomplished, you turn your back on me as your enemy, and you go back to your God, who being benign and merciful, pardons you and receives you willingly. But make me a promise, written and signed by your own hand, that you voluntarily renounce Christ and your baptism and promise that you will adhere and be with me to the day of judgment, and after that you will rejoice yourself with me to suffer eternal pains; and I will accomplish your desire.

Dee sighed. His divinations for ancient Arthurian and Druidic treasure were not going well, and Queen Elizabeth was demanding more money to aid in the fight against France and Spain. On top of that, the expeditions to the Americas and Russia had not had much success either, despite all of his briefings and his charts. What he needed, he thought, was a man who could hear the voices of angels. Then together they could decode the secrets of the universe.

Dee’s search led him to the town of Lancaster, where a man named Edward Kelley claimed that he could speak with spirits. Dee found him in the centre of town, locked in the stocks for passing off fake coins and horoscopes.

‘So you are the famous Edward Kelley,’ said Dee.

Kelly looked up at him as best he could. ‘Have you come to gloat?’

‘No. I’ve come to see if you can really hear the angels.’

‘Their voices fill my head.’

‘With truth or lies, I wonder,’ said Dee.

‘Angels cannot lie.’

Dee laughed. ‘A bit of circular logic, perhaps, but well said. I have a proposition. If you agree to come and work for me, I will get you out of your current entanglement.’

A few months later, Dee walked into his lab where Kelley was working.

‘Today is the day, Kelley,’ Dee said, ‘I wish to speak with the angel, Uriel.’

Kelley got to work on the preparations, fasting all morning and praying in the small chapel attached to their library. In the afternoon, Dee put him into a trance, and Kelley began dictating notes from the angel Uriel. While Kelley spoke in the strange language of the angels, Dee wrote every word down meticulously.

‘One moment,’ Dee interrupted. ‘How should I spell that name?’

‘A-N-N-I-E-L.’

‘That’s what I thought you said,’ Dee muttered. ‘And it’s wrong. It should have only one N, as an angel should know.’

He looked at Kelley suspiciously. For months they had worked together like this, and Dee’s journals were already filled with notes in Enochian, the language of the angels.

If Kelley were lying, the months would have been wasted.

‘No,’ Dee muttered to himself. ‘You can’t be lying to me. No one would be so foolish…’

The image we have of an old wizard’s study or laboratory in his tower, or his office in Hogwarts, is very much derived from contemporary illustrations of the environs of Dr Dee and his ilk. The books, jars, sextants, stuffed crocodiles, and so on that we expect to see in such a room are exactly what you would have seen in Dee’s home at Mortlake.

More accurately, it was Dee’s mother’s home in Mortlake, which Dee expanded, buying up all the neighbouring houses so that he could expand his library and collection of esoteric artefacts – magic mirrors, globes made by Mercator, the Voynich Manuscript, etc – into them. In its day it was the biggest library in Europe.

One day, Kelly brought home a man named Albert Laski and introduced him to Dee. Laski was a noble from Krakow, and he suggested that Kelley and Dee join him at his estate when he returned there. He claimed to have worked for the king, and promised them full access to his vast library. It was a tempting offer to a book collector like Dee, and when an angel, speaking through Kelley, also urged him to go, he decided to make the trip.

When Dee and Kelley arrived in Krakow, they went directly to see King Stefan, to announce their arrival. When the king heard why the two men had come to Poland, he laughed.

‘Laski,’ said King Stefan, ‘that bankrupt old blowhard? The only books he could show you are the ones holdings his bills at the local tavern.’

Dee got a sinking feeling in his stomach and asked, ‘then there is no work for us either?’

‘Not for Queen Elizabeth’s spy, no.’ The king frowned. ‘Look, you’re a respectable man, and your friend Kelley here is popular. Perhaps you should go to Prague Castle. King Rudolf is known to be a good friend to magicians.’

This 19th-century engraving casts Dee and Kelley as necromancers conjuring the spirit of a woman at her grave, though this is not a type of magic with which the pair were actually involved. (Mary Evans/Interfoto)

Rudolf II was a man ahead of his time, both fascinated by the natural world and convinced of the human ability to progress. His freethinking, Protestant court became a haven for the alchemical and magical cream of Europe and those persecuted as opponents of the Catholic worldview. The famous astronomers Tycho Brahe and Giordano Brunowere were visitors, as were John Dee and Edward Kelley. Kelley ended up imprisoned in the round tower of the castle of Prague, to this day known as ‘The Alchemists’ Tower’.

Rudolf was so keen on the allegorical images of alchemy that he planned the palace gardens as an alchemical journey through a landscape of bronze and other metal figures, streams, and allegorical set pieces. Sadly only part of it was completed before his death, but the plans remain.

Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, alchemist, and maths fan in a Flemish portrait. (The Art Collection / Alamy)

Rudolf had a vast menagerie of beasts, including several lions. His favourite, Ottokar, is said to have shared its birthday with Rudolf and to have behaved quite tamely.

Rudolf died on 20 January 1612, three days after Ottokar. There were quite a few lions named Ottokar in Prague over the years, named after the 13th-century Bohemian King Ottokar, whose insignia was a two-tailed lion.

‘He must be a wise man,’ Dee said.

The Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia, indeed proved a good friend to Dee and Kelly. Dee had rarely met someone so interested in collecting magical esoterica and materials connected with the natural sciences, and his library was second to none. Upon their arrival, the king immediately found work for the two men.

One day, some weeks after their arrival, all three men were sitting in the library.

‘This is a fascinating book,’ said Rudolf II, leafing through a thick volume filled with indecipherable text and drawings of unearthly plants. ‘How did you come by it?’

‘It was given to me by a stranger,’ Dee said.

‘And written by an angel,’ Kelley added. Dee glared.

‘I should like to add it to my collection. How much would you want for it?’

‘Consider it a gift,’ said Dee.

This time, it was Kelley who stared angrily.

A few days later, Dee and Kelley were speaking with the angel Uriel, when Uriel said, ‘You must combine your natures more completely. Suns and moons together. Each sun to the other moon.’

Dee stopped writing and looked up in astonishment. ‘Are you suggesting we should trade wives?’

‘Only then can our meetings continue,’ Uriel said through Kelley.

Dee closed the book he was writing in and brought Kelley out of his trance.

I fear,’ said Dee ‘that we have learned all that we can from Uriel. Tomorrow, I am returning to England.’

‘If you must,’ said Kelley, with a barely contained grin.

A few days later, as they packed their luggage onto a coach, a group of soldiers approached and surrounded them.

‘Are you arresting us, or throwing us out?’ Dee asked.

The captain replied, ‘You can go, Dee, but he stays here.’

Dee opened his mouth to object, but then he remembered the suggestion to swap wives. He remembered Kelley’s angels’ misspelt words, and he remembered his initial meeting with Kelley, when he found him the stocks.

Dee said nothing as the guards dragged him away. It was only sometime later that Dee heard what happened to Kelley. It seemed that Kelley had been up to his old tricks of making fake gold coins. Unfortunately for him, the trick had managed to even fool the king. Kelley now spent his days locked in a tower, making counterfeit gold for the king.

John Dee was a mathematician, cryptographer, and unofficial court philosopher to Queen Elizabeth I. He was never an official court magician because Britain viewed such a position as an unnecessary luxury and was unwilling to pay a wage for it.

A 16th-century portrait of John Dee. The globe and compass reflect his early interest in mapmaking, as well as being his tools for astrology and casting of horoscopes. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

At the time, Dee was viewed both as a bit of a wizard on political grounds – he changed sides more than once during religious upheavals on either side of the reign of ‘Bloody’ Mary – and as Britain’s first proper scientist and thinker. He taught Elizabeth I about alchemy, which was a subject of great interest to a monarch looking to replenish her coffers after many military campaigns. Although we view the Elizabethan period as a ‘golden age’, it was actually a time of austerity, and treasure hunting was a national pastime. People believed that gold grew from the actions of the sun on the earth at the tropics – which was a major reason for founding colonies there – and Dee himself leased gold mines.

Dee was first referred to as ‘Dr Dee’ in a letter about his religious position during Mary’s reign, but was actually awarded a doctorate later in life. He originally wanted to be a cartographer and was a friend of Mercator. In fact he provided the charts for the search for the fabled North West passage around the top of the Americas, but then turned to mathematics and cryptography. He believed that spirits and angels could help him decode the secrets of how the universe worked in a scientific manner.

Dee always had a reputation as a sorcerer; his London home was shunned by the local urchins for fear of magical reprisals. By careful purchase of surrounding property he built a space big enough to house the greatest library in England. None of it was catalogued, though it was said that Dee knew it so well that he could immediately lay hand on any volume in the whole edifice.

Dee’s own view of magic, however, was less sensational and more practical. He insisted that a true magician was first and foremost a mathematician, and that his magic was based on the natural sciences, not superstition, which he despised. He anticipated Newton’s discovery of gravity by imagining a magnetic-like force that bodies exerted on one another, and his finest contribution to magical literature was probably the Monas Hieroglyphica, which explained his view of the cosmos, and related it to a symbol he had created.

After his trip to the court of Rudolf II, Dee returned to England to find that his library had been looted. He was eventually given a post at Christ College at Manchester.

The Devil straightened his red-lined opera cloak and stepped into the private theatre box. God was already sitting there, quietly reading the programme, his immaculate white suit glowing faintly in the dimness.

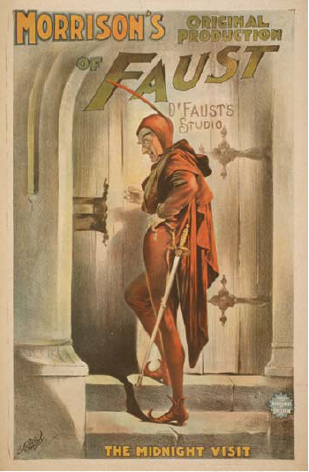

A wonderful, painted Mephistopheles on a poster for a 19th-century American stage production. (Library of Congress)

‘Is this seat taken?’ asked the Devil.

‘Be my guest,’ God replied. His angelic smile beamed from his full-bearded face.

The devil took his seat, and the shadows thickened around it. ‘It’s been a while,’ he said.

‘And, if you don’t mind me saying, you do seem to have rather come down in the world these days,’ replied God with a chuckle.

‘I do mind,’ the Devil replied. ‘Popularity is a matter of marketing, and we don’t all have your resources.’

‘Sssh, it’s about to begin.’

Slowly, the curtain rose on the theatre of the world, and the small audience looked down on a cluttered study …

A man in a velvet doctor’s cap walked into the study. He sighed and looked around, his face revealing his frustration and boredom. He grabbed a book, flipped through it, and then tossed it aside. He did this again and again, his frustration mounting, until he opened one book and froze. He read intently, flipped a page, and read on.

Suddenly with a clap of thunder and a burst of light, the demon Mephistopheles appeared in the study. He introduced himself to Faust, and said that he had come with an offer from the Devil himself. Nearly limitless magical power for a term of 24 years, one year for each hour of each day, at the end of which, Hell would claim his soul. Mephistopheles wiggled his fingers and a contract appeared.

Faust read the contract quickly, then grabbed a quill and signed.

In an instant, the scene changed. Faust and Mephistopheles entered a tavern. The demon hammered a wooden tap into a bench, then turned the tap and released a stream of wine. The tavern-goers swiftly took advantage of it, got drunk and started brawling. During the fight, one man was decapitated, but managed to recover his head and reattach it. At this point, Faust and Mephistopheles made their exit, riding on a living barrel of wine.

In the next scene, the man and the demon stood on the street as a beautiful young woman passed. Faust looked on her with lust-filled eyes, while the demon arched his eyebrows and gave a knowing grin.

Up in the box, God turned his head and covered his eyes.

The Devil laughed. ‘You can’t stop watching now. It’s just getting interesting. That’s the price of omniscience!

‘That doesn’t mean I have to enjoy it.’

Back on stage, Faust used his dark magic to seduce the beautiful Gretchen, killing her mother and brother in the process. Later, when Gretchen gave birth to Faust’s child, she drowned the baby in the river and was arrested for murder. Faust and Mephistopheles broke into the prison in order to free the girl, but she refused to be rescued, insisting that she must pay for the evil she had done.

Eventually, Gretchen was executed, but, because of her repentance, angels came and carried her soul up to heaven.

The Devil has been portrayed in many different ways over the centuries, but has never been more dapper than when, in the form of Mephistopheles, he bargains with Faust – or Dr Faustus, depending on which version you’re reading – for his soul in return for money, women, success, and fame.

In fact, the Devil as a proactive figure who tempts humans to commit evil, and is portrayed in art as the source of evil, is, perhaps surprisingly, a 14th-century take on the character. Before that, he actually worked for God, as his jailer, rehabilitating souls in Hell. This is reflected in those versions of the Faust tale in which God and the Devil are not quite enemies at each other’s throats all the time, but share a certain responsibility in their wager over Faust.

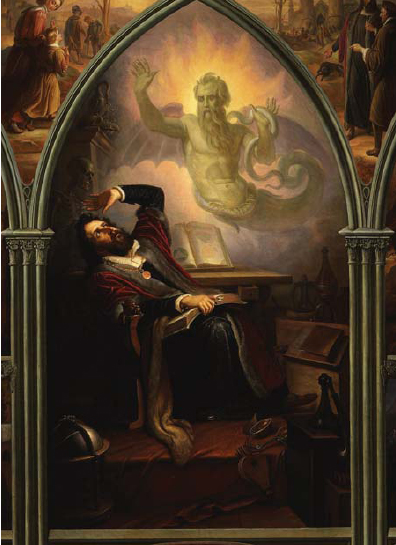

Carl Vogel Von Vogelstein depicts scenes from Goethe’s version of Faust, with a much more demonic Mephistopheles, harkening to the serpent in the Garden of Eden, tempting the protagonist. (The Art Archive / Alamy)

‘Typical,’ muttered the Devil.

From then on, the scenes became a blur of strange happenings and classical allusion. Faust and Mephistopheles travelled through time and the cosmos, on a search for ultimate beauty. Their journey eventually led them to classical Greece and Helen of Troy, where the pair got involved in the affairs of the ancient gods, heroes and monsters.

Eventually, the 24 years had almost expired …

The Devil stirred in his seat. ‘It’s all rather predictable, especially the deus ex machina to save the girl.

‘Finding fault again,’ replied God. ‘Now that is predictable for you.’

The two locked eyes.

‘Faust is mine,’ hissed the Devil.

‘We shall see,’ said God. ‘This story isn’t over yet …’

Not only was there a historical Faust, there were actually two. Johann Faust was a German astrologer and physician probably born near Heidelberg in 1480, who was booted out of Ingolstadt in 1528 due to his homosexuality. Since he was already an astrologer, being persecuted for what were viewed as unnatural practices of another kind contributed to his reputation as a sorcerer.

This reputation was completed by the nearly contemporaneous existence of a Georg Faust, born in 1466 in Gelnhausen, who also had trouble in Heidelberg in 1506. He was a known conman and trickster who had been accused by the Church of trading with the Devil.

Whether the two Fausts were related is unknown, but they have since often been combined into a single figure named Johann Georg Faust. One or the other of them was killed in an explosion – a frequent cause of death among alchemists of the era – in 1548, his body so damaged that it was thought to have been torn apart by a demon.

Faust is said to have hosted dinner parties for his students at which spirits appeared and served 46 different courses with wine which mysteriously appeared from holes in a tavern. He reportedly cursed the unfriendly monks of a local convent with a poltergeist, conjured up the heroes of Greek mythology in front of his students to illustrate his lectures and burned off a clergyman’s beard with arsenic.

Most famously he collaborated with the Devil in the form of Mephistopheles, with whom he signed a pact in his own blood, exchanging his soul for eternity to gain wisdom, riches, and success. The Faustian pact has been a trope of literature, legend, and culture ever since. Medieval texts are full of complex contracts to avoid trickery on the part of supernatural powers. One specifies that the spirit’s gold ‘shall not be false nor of any material that can be cheapened or disappear into coal or anything of that kind’.

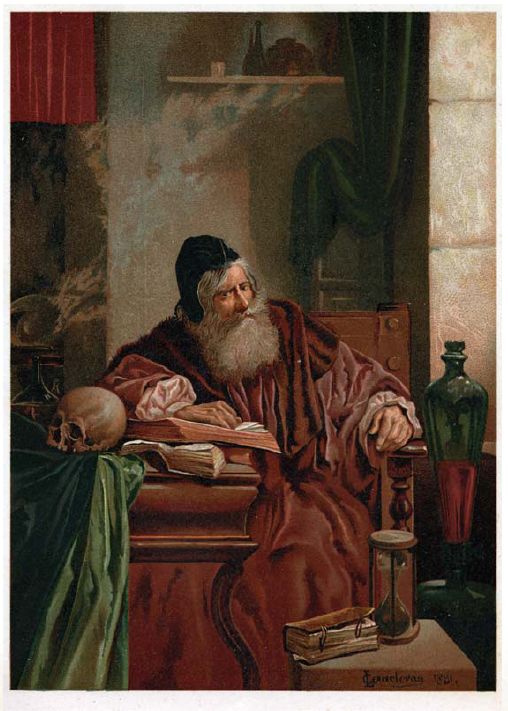

A portrait of Faust at his studies in the normal way, rather than the supernatural way. (Library of Congress)

The Faust best known today is Goethe’s 19th-century character. In Goethe’s play, Faust the scholar laments that he has studied everything known, but is no cleverer than before, so he gives himself over to the Devil in order to understand the inner workings of nature. This Faust is torn between inadequacy and feeling equal to God in the use of his God-given reason. He is also held back by a lack of money, which would be understood in every era. Mephistopheles is also dissatisfied with his life, because all his attempts to do evil end in something good.

Goethe’s Faust is saved by the intervention of his beloved Gretchen, but the original legend of 1589 doesn’t end so happily. Faust refuses a priest’s attempt to save him by saying Mass, because the Devil never broke his side of the bargain, so why should Faust? Faust’s students cower as the whole house is rocked by an earthquake, there are terrible screams and Faust’s corpse is found with its head on backwards.

There are many famous magical books. Here are five of the best for the discerning wizard’s bookshelves.

1. Key of Solomon (Clavicula Solomonis), supposedly written by the Old Testament king but probably early medieval. This book contains words for binding spirits and the names of angels for every hour and for every activity. There is even one, called Raziel, for libraries, as well as a minor demon by the name of Humots, whose job it is to ‘transport all manner of books for thy pleasure’. Each spirit has a ‘sigil’ or symbol, which the wizard can draw in order to summon him. It was printed in the Sworn Book of Honorius (14th century) and by 19th-century magician A. E. Waite as The Ceremonial Book of Magic.

2. Paracelsus, De Libera Nymphis, Salamandris, Sylphis, Gnomibus, et Caeteris Spiritibus (The Book of Nymphs, Salamanders, Sylphs, Gnomes, and Other Spirits). A guide to magical creatures that share the world with man and can become his friends, enemies or servants. The nature of each group is related to the element in which they dwelt. Salamanders, living in fire, were a symbol for alchemical gold. Sylphs lived in the air and could be mistaken for people, except they were taller, paler, and thinner. A man and a sylph could marry and have a family, as could a man and a water-spirit. But he must be careful never to scold her near water, lest she disappear! Gnomes, being of the element earth, were trustworthy, dependable, and could show you buried treasure, but people had to be careful to pay their wages on time.

3. Cornelius Agrippa, De Occulta Philosophia (On Occult Philosophy). A work considered to be the medieval bestseller on magic, alchemy, and astrology. So popular was this book that an ‘Agrippa’ became the name for a magical book in general. The other common name for a magical book was a grimoire, named after The Grand Grimoire.

4. Pope Honorius III, The Grand Grimoire. This is a set of four guides to summoning the Devil and demons. Honorius, who claimed to be the head of a European council of 811 wizards, launched a call to arms for wizards against persecution by the Church during the reign of Pope Gregory IX, insisting that the Church, not the wizards, was in league with Satan, as spirits would never work with anyone who was evil.

5. The Shemhamphoras. A Hebrew text taken from the words for the number 72. Using the numerical value of Hebrew letters, this book claimed to be a guide to finding 72 magical names of God. Oddly enough, the most secret one adds up to 811, the number of wizards in Honorius’s council.