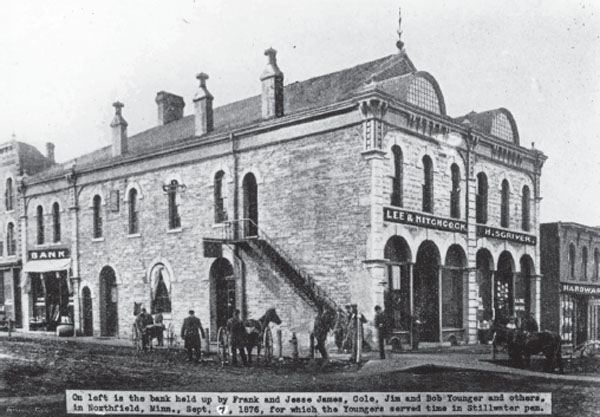

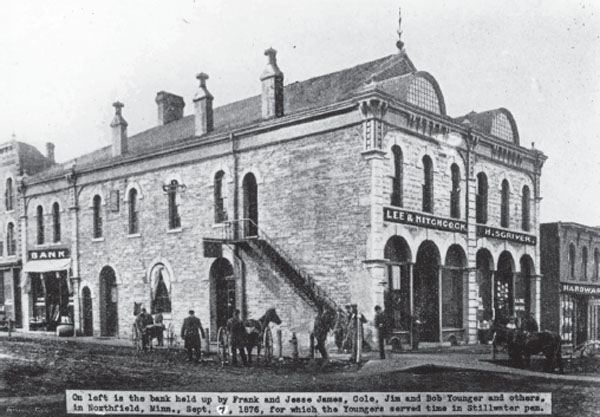

First National Bank, Northfield, Minnesota. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

2

THE DALTONS

A LOVELY AUTUMN DAY IN KANSAS

They rode in through a brilliant October morning in 1892, laughing together and “baaing” at the sheep and goats in the fields along their way. They seemed to be out on a casual ride; instead, they planned to rob two banks in the pleasant little town of Coffeyville, Kansas, and kill anybody who got in their way.

Three of the young men were brothers named Dalton, and they knew Coffeyville, for the Dalton family had lived nearby for several years. They were going to do what they thought nobody had ever done before: rob two banks at once. In the main square of the town stood the Condon and First National. The citizens were peaceful people. It should be a piece of cake. Nobody in town even carried a gun anymore, not even the temporary town marshal, who in any case was a school principal by profession.

This strike was going to be a big one, and it would finance their exodus from Kansas and Indian Territory, where the law wanted them badly. Tough deputy U.S. marshal Heck Thomas was on their back trail, only a day or so behind them, for during their last holdup at Adair, down in the territory, they had shot down a couple of unarmed, inoffensive civilians as they galloped out of town. Worse, both the men they had shot were doctors—a jealously protected species in the West—and one of their victims was dead.

Two banks at once was a feat never equaled even by the Dalton boys’ famous cousins, the Younger brothers, now languishing in a Minnesota prison, much less by the Youngers’ boon companions, Frank and Jesse James.

First National Bank, Northfield, Minnesota. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

“Death Alley,” Coffeyville. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

Coffeyville was wholly unprepared for a raid from the most notorious outlaw gang of the day still on the loose. The gang might have gotten away with stealing the citizens’ savings—except for Coffeyville’s penchant for civic improvement. For the town was paving some of its downtown streets and had moved the hitching rack to which the gang had planned to tether their all-important horses. Since the gang had done no reconnaissance whatsoever, this came as a complete surprise. “Well I’ll be damned,” said Bob Dalton somewhat unnecessarily. “They’ve taken down the rack.”

So they rode around the busy streets until they found a spot to park their mounts in an alley, behind the police judge’s house. They tied the horses to a fence in the alley—it’s called “Death Alley” today—and walked together down toward the square, five dusty men carrying Winchesters in a peaceful town where the Daltons were known and nobody else carried a weapon. They were immediately spotted by at least one citizen who knew the family, and the word spread quickly.

They crossed the open plaza and walked into the two unsuspecting banks. Tall, handsome Bob Dalton was the leader, a reasonably bright man with a fearsome reputation as a rifleman. Grat, the eldest, was a slow-witted thug whose avocations were beating on other people, gambling and sopping up prodigious amounts of liquor. As writer Harold Preece put it, “Grat had the heft of a bull calf and the disposition of a baby rattlesnake.”

Emmett, or “Em,” was the baby of the lot, only twenty-one on the day of the raid but already a seasoned robber. Backing the Dalton boys were two more experienced outlaws, Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers. Powers was a Texas boy who had punched cows down on the Cimarron before he decided robbing people was easier than working. Broadwell, scion of a good Kansas family, allegedly turned bad after a young lady stole both his heart and his bankroll and left him flat in Fort Worth. Perhaps because he was reluctant to split the expected booty more than five ways, Bob left behind several veteran gang members, like Bill Doolin, Bittercreek Newcomb and Charlie Pierce.

Grat Dalton led Powers and Broadwell into the Condon Bank. Em and Bob went on across the street to the First National. Inside, they threw down on customers and employees and began to direct the bank men to deliver the banks’ money and be damn quick about it. Next door to the First National was Isham’s Hardware, which looked out on the front door of the Condon, into the Plaza and thence down Death Alley to where the gang left its horses, three hundred feet or more away. Isham’s and another hardware store started handing out weapons to anybody who wanted them, and there were over a dozen takers.

Inside the First National, Bob and Emmet had gotten a sackful of cash, in spite of the bankers dragging their feet. The brothers finished up their looting, collected some hostages, pushed out the door into the Plaza—and then all hell broke loose in Coffeyville.

Condon Bank, Coffeyville, with windows full of bullet holes. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

Condon Bank, Coffeyville, as it is and was. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

The first shots were fired at Emmett and Bob, who dove back into the First National. Bob shot one citizen through the hand, and then he and his brother ran out the back door. The two kept going, circling around through a side street, out of sight of the waiting citizens, along the way killing a young store clerk. Bob was ready, he told his brother, to do the fighting. Emmett’s job was to carry their loot in the grain sack that was standard equipment for the robbers of the day.

Inside the Condon Bank, Grat had collected a sackful of silver so heavy that it would take more than one man to carry it. Then, when he demanded the vault be opened, courteous young Charley Ball looked Grat in the eye and blandly announced that the time lock to the vault (long since opened) would not unlock for several minutes. “Eight minutes,” crowed a later newspaper report, “was the time consumed by Cashier Ball in his one-act skit of ‘the Bogus Time Lock.’”

That eight minutes saved the bank treasure and cost the Dalton gang its existence.

While Ball courageously sold gullible Grat Dalton on this colossal fib, another employee helpfully rattled the vault doors to complete the illusion. He didn’t pull on them, of course, because they would have swung open.

Grat, instead of trying those doors himself, stood and waited for the hands of the clock to move, while outside the townsmen loaded Winchesters and found cover. About the time thick-headed Grat began to suspect that he was being had by Charlie Ball’s honeyed words, somebody outside fired a shot. Hell in Coffeyville was in session. A pair of house painters bailed off their scaffolding and hit the ground running, women shooed their children indoors and the gathering of defenders over at Isham’s opened up. One especially courageous soul even crawled out on a porch roof and began popping away with a pistol.

Bullets began to punch through the windows of the Condon Bank; one tore into Broadwell’s left arm. “I’m hit!” he yelled. “I can’t use my arm!” Grat, Broadwell and Powers could not match the firepower of the citizens, as some two hundred projectiles of various sizes slammed into the windows and façade of the Condon. One defender at Isham’s was hit in the chest by a rifle round and knocked flat—but all he got from the outlaw bullet was a bruised chest, for the slug had hit an iron spanner (wrench) he carried in his shirt pocket.

The townsmen’s heavy, accurate fire convinced even dull-witted Grat that maybe it was high time to go. Leaving behind their enormous heap of coin, the three outlaws charged out into the bullet-swept Plaza, straight into the line of fire of the rifles at the hardware store, running hard for their horses, now so very far away down the alley. There was no cover for them anywhere, and they were being shot at not only by the citizens in the hardware store but also by men firing from the offices upstairs in the Condon.

They didn’t have to run that impossible gauntlet. Grat could have led his men around the corner on which the bank sat. Had he done so, they would have been out of the line of fire from Isham’s in just a couple of strides. Or he could have sought the bank’s back door. Instead, Grat led his men out into the plaza in front of the bank, directly into the killing zone, running hard for the alley and snapping shots at that deadly nest of rifles inside Isham’s Hardware. All three outlaws were hit before they reached their horses. Witnesses saw dust puff from their clothing as rifle bullets tore into them.

Meanwhile, Bob and Emmett ran out of the First National, down the alley behind the bank and around a block, staying out of the defenders’ sight. They came in behind some townsmen still facing down the street toward the First National and the Condon, and Bob shot down a shoemaker armed with a rifle. An old Civil War veteran who was now a cobbler courageously reached for the fallen man’s weapon, and Bob killed him, too. Bob drove a round through the cheek of still another citizen as the outlaw brothers ran on, trying to reach Grat and the all-important horses.

They kept buildings between them and those deadly rifles and emerged in the alley about the time Grat and the others got there. About the same time, town marshal Charles Connelly appeared in the alley from another direction but miscalculated the position of the fleeing outlaws and came in between them and their horses. Grat Dalton, already wounded, shot the lawman down from behind. Liveryman John Kloehr, the town’s most expert shot, then put Grat down for good with a bullet in the neck.

As Bob and Grat ran into the alley, somebody—or several somebodies—nailed Bob Dalton, who sat down on a pile of cobblestones. Still game, he went on working his Winchester for several aimless shots, one of which tore into a box of dynamite over at Isham’s—without effect. Kloehr drove a bullet into Bob’s chest, and the outlaw leader slumped over on his side and died in the alley. Powers lay dead in the dust about ten feet away.

Broadwell, mortally wounded, managed to get to his horse. He rode about a half mile toward safety before he pitched out of his saddle, dead in the road. Young Emmett, still carrying the grain sack of loot from the First National, miraculously managed to get mounted. Hit several times in quick succession, he jerked his horse back into the teeth of the citizens’ fire, reaching down from the saddle for his dead or dying brother Bob. There’s a good deal of mythology about Bob’s last words to his brother: “Don’t surrender. Die game!” Or maybe Bob said something similarly heroic, as Emmett, never renowned for slavish adherence to the truth, claimed decades later. Or maybe Bob said nothing at all.

Bob (left) and Grat Dalton, finished in Coffeyville. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

About then, the town barber, Carey Seaman, blew Emmett out of the saddle with both barrels of his shotgun.

Four citizens were dead. Three more were wounded. The man with a rifle slug through one cheek was hurt very seriously indeed and at first was expected to die. Four bandits had also died, and Emmett was punched full of holes—more than twenty of them. He was carried up to the second-floor office of Dr. Wells, who set out to save the young outlaw’s life.

While the doctor was at work, a group of citizens, understandably angry at the death of four of their friends, appeared in the doctor’s office carrying a rope. They planned to tie one end to a telegraph pole outside the doctor’s window and the other end to Emmett and then throw him out the window. “No use, boys,” said the doctor. “He will die anyway.” One citizen spoke up. “Are you sure, Doc?” “Hell, yes,” said Dr. Wells. “Did you ever hear of a patient of mine getting well?” That broke the tension, somebody laughed and Emmett was saved for trial and a long spell in the Kansas state penitentiary.

The four expired bandits were propped up to have their pictures taken after the custom of the time, and people came from everywhere to see the corpses and collect souvenirs: bits of bloody clothing, hairs from the dead horses and so on. Some brought their kids, thinking that the edifying sight of dead bandits might be helpful in keeping the young on the straight and narrow. Some sightseers indulged in a macabre hydraulics experiment; if you worked Grat’s arm up and down like a pump handle, blood squirted out of the hole in his throat.

Dalton Gang, end of the trail, Coffeyville. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

And so passed the Daltons in one of the most famous and badly planned and executed holdups in the history of crime. Bob and Grat are still in Coffeyville, up in the cemetery. They have a headstone these days, but planted alongside it is a piece of ordinary pipe, long their only monument and still the most enduring one.

It’s the pipe to which they tied their horses in that deadly Coffeyville alley.