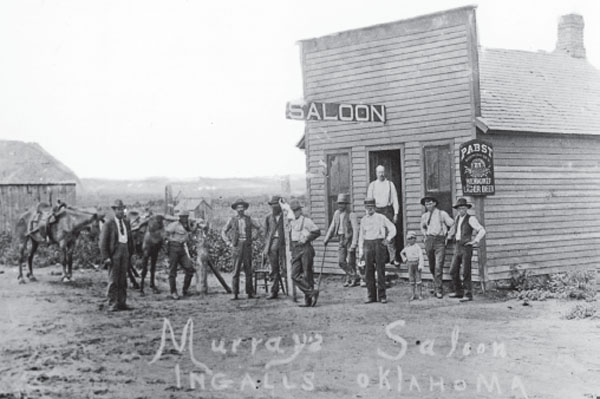

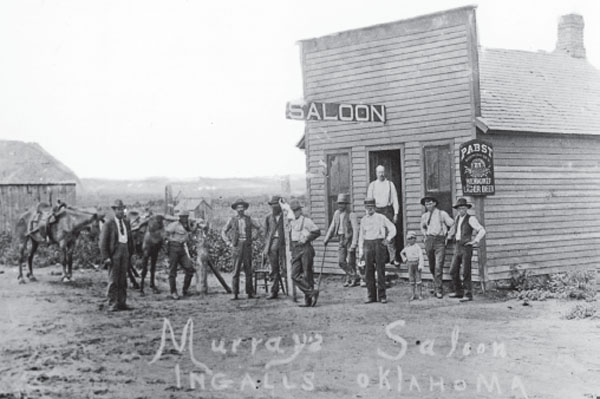

Outlaw Roost, Ransome and Murray Saloon, Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

3

BILL DOOLIN

GUNFIGHT AT THE OK HOTEL

There wasn’t much to look at or do in Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory, that Friday morning, September 1, 1893, five months after Bill Doolin had married a local girl. And even today, only an aging historical marker and a ramshackle replica structure or two commemorate the place. Yet that morning, 123 years ago, one innocent bystander was mortally wounded, and three lawmen and a young man were killed by the notorious Bill Doolin gang, all of whom escaped save one.

Outlaw Roost, Ransome and Murray Saloon, Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

THE INGALLS BATTLE , SEPTEMBER 1, 1893

Bill Dalton, Dan “Dynamite Dick” Clifton, William “Tulsa Jack” Blake and Doolin himself were playing cards that morning in a one-story shack called the Ransom Saloon. Their business associate Bitter Creek Newcomb went out in the street to check on their horses, only to see a young boy named Del Simmons point him out to a stranger nearby. And the stranger, deputy U.S. marshal Dick Speed, wasn’t in town for the bad liquor and worse food.

The feds had learned the previous day that the Doolins were in Ingalls and put together two wagons full of law enforcement officers and posse members to round them up. Jim Masterson, brother of noted gunfighter and Wyatt Earp compadre Bat Masterson, hurried out of nearby Stillwater at sunset the previous evening with four other deputies even as a second five-member federal posse led by Speed left Guthrie to join in the pursuit.

Speed arrived just in time to get himself killed, but Bitter Creek didn’t do the deed. That Friday morning, Roy Daugherty, known in Oklahoma and Indian Territories as Arkansas Tom Jones, was recuperating from a hangover or illness on the cramped second floor of the so-called OK Hotel nearby when he heard the commotion downstairs. From his second-floor window, Daugherty killed Speed and the young Simmons boy (possibly by mistake) and may have also killed the two other deputy U.S. marshals and a traveling salesman, who died later that day.

This wasn’t even the first significant large-scale gunfight in the place we now call Oklahoma. On April 15, 1872, at Flint, near the Arkansas border, nine years and five months before the Tombstone, Arizona Territory “Gunfight at the OK Corral” in which the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday shot down three men who were resisting arrest, Ezekiel “Zeke” Proctor was being tried in a Cherokee court for the murder of one Polly Beck, whom Proctor had killed during an argument with her husband, perhaps accidentally. Polly’s family didn’t trust the tribal court and asked the federal court at Fort Smith, Arkansas, to intervene. As many as eleven people were killed that day in the “Going Snake Massacre,” a gunfight between Cherokee tribal members and federal marshals. And it happened during a murder trial. The judge, one juror and several spectators were wounded.

Doolin was born in Johnson County, Arkansas, three years before the American Civil War but left home at about age twenty-three in 1881. Not much is known for sure about his early life in the Oklahoma and Indian Territories, other than that he worked as a ranch hand before getting into trouble for the first time in Coffeyville, Kansas, during July 4 festivities in 1891. He briefly exchanged gunfire with local law enforcement officers after trying to buy some beer.

Some sources claim that prior to that incident, Doolin met Emmett Dalton of the notorious Dalton gang while working on a ranch near present-day Pawnee, Oklahoma. In his late life memoirs, Emmett claimed that Doolin was among five men who had joined the Dalton gang two months earlier for a May 15 Santa Fe train robbery near Wharton (present-day Perry), Oklahoma Territory.

And Doolin may have participated in other Dalton gang train robberies, among them the mid-September 1891 job at Leliaetta near Wagoner, Indian Territory, and a June 1, 1892 robbery at Red Rock near Marland in present-day Noble County, which yielded $75,000, some $1.9 million in modern money. Perhaps Doolin also participated in the last Dalton gang train robbery at Adair, Indian Territory, on July 14, 1892, in which a doctor was killed.

HARD TIMES IN THE ROBBERY BUSINESS

Following the Adair job, the Dalton boys downsized their gang, discharging Doolin and several others. But in doing so, they had done Doolin and the other displaced robbery workers a big favor. For on October 5, 1892, during a raid on Coffeyville, Kansas, every remaining member of the Dalton gang except Emmett was killed. There is no real evidence that Doolin was anywhere near the Coffeyville debacle.

Most historians consider the $1,500 robbery of a DM&A train at Caney, Kansas, which occurred seven days later, to be the first Doolin gang job, an organization that stole some $165,000 in six years, about $4.6 million in modern money.

George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb, Charlie Pierce, Ole Yantis and perhaps Bill Dalton, a younger brother of the doomed Coffeyville brothers, may have also joined up by then. Whoever was with him, Doolin and his gang struck again in Kansas on November 1, 1892. This time, they robbed the bank at Spearville, drawing the ire of Ford County sheriff Chalk Beeson, who promptly drove a horse team down to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory; got himself sworn in as a deputy U.S. marshal; and raised his own posse.

Beeson and the others surrounded a house near Orlando in northwest present-day Logan County, where Ole Yantis was staying with his sister. After Yantis died trying to escape, the posse found a wad of money from the Spearville bank in his pocket.

And with this, the Doolin gang went dead silent again until June 3, 1893, at about 1:20 a.m., when they robbed a Santa Fe train at Cimarron, Kansas. The Meade County Globe reported the next day:

The train had just pulled out of that town when the engineer saw a danger signal near the bridge and stopped the train, when two of the men jumped onto the engine and with revolver drawn commanded the engineer to go with them to the express car with a sledge hammer to batter in the door. When they arrived the messenger refused to open the door and after firing some shots into the car they blew the door off with dynamite. They had shot the messenger through the side and disabled him. The robbers took the contents of the way safe and commanded Whittlesey to open the through safe but he could not do so. It is thought they secured about $1,000 in silver, and mounting their horses rode off to the south .

The Globe also reported that the next morning, the county sheriff in Meade, Kansas, received a telegram from Cimarron informing him of the robbery and instructing him to be on the lookout just as the Doolins rode their horses east of Meade. In fact, a local judge saw them as they passed the corner at his place going south. Soon after, the sheriff and a deputy gave pursuit but couldn’t find them. The Doolin crew dined that evening at a ranch ten miles southeast of Meade. The next day, a Kansas rancher named John Randolph entertained the Doolin gang at breakfast, as the Meade County Globe reported on June 22:

They stopped at his place about 11 o’clock on that morning and wanted their dinner. Said they had been after a horse thief. They said they were in a hurry and to get them a bite quick. They unsaddled their horses and fed them, leaving their Winchesters on their saddles. Going into the house they sat down a few minutes to wait for the preparation of the meal and in that many minutes were all sound asleep in their chairs. When dinner was ready John awoke them, little thinking he had in his house four men who were desperate robbers and for whose capture there was a reward of $10,000. It is safe to say that had honest John known this he would have bagged them and by this time had a snug little fortune down in his jeans—but he did not know it—so there’s the rub. But at any rate he got a good squint at them, and will know them if he ever sees them again .

Randolph told the Globe that the gang “seemed just as quiet and serene as though they had been common farmers who had dropped in to pass the time a day. John says they were all gentlemanly in their actions and seemed well bred.” A little over two months later, the Doolin gang proved otherwise at Ingalls.

Doolin had met his wife, Edith, the daughter of a local minister named Ellsworth, in Ingalls. And only three months after the early September 1893 Ingalls gunfight, newspapers reported that he was camping nearby. Some say that he celebrated the New Year by robbing a Payne County postmaster, but more certainly, on January 23, 1894, Doolin and several others robbed the Farmer’s and Citizen’s Bank in Pawnee.

That very day, U.S. marshal E.D. Nix, just returned from Washington, publicly denied recent newspaper articles claiming that he was trying to arrange for Doolin and his gang to surrender in exchange for two-year sentences.

Almost five months later, on May 10, 1894, Doolin led his only raid into Missouri, mortally wounding former state auditor J.C. Seaborn after robbing a bank at Southwest City near the Indian Territory border.

That killing drew the immediate attention of E.D. Nix, the federal U.S. marshal for Oklahoma Territory, who dispatched deputies Heck Thomas, Chris Madsen and Bill Tilghman, known then as “the Three Guardsmen” to find the Doolin crew.

Meanwhile, Frank Dale, chief justice of the Oklahoma Territory, wrote to the United States attorney general on June 16, 1894, that he had seen Bill Doolin several times in the past two or three weeks. Dale told the attorney general that Doolin was “anxious to drop the business he is in and will willingly come in and give up, provided he can have fair treatment and not too long a term in the Pen.” Two days later, Bill Dalton was killed near Ardmore, Indian Territory. And nothing came of the Doolin gang surrender initiative.

As it turned out, the Doolin gang robbery of a Rock Island train at Dover, Oklahoma Territory, in the southern reaches of present-day Kingfisher County in early April 1895, was their last hurrah. By now, Doolin was suffering from consumption, rheumatism aggravated by several gunshot wounds or both.

Bill Doolin, death by shotgun. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

Deputy U.S. marshal Tilghman stepped off a train in Guthrie shortly after noon on January 16, 1896, with Bill Doolin himself, neither shackled nor handcuffed. Oklahoma Territory newspapers told competing stories of the capture. In the most frequently told version of events, Tilghman trailed Doolin to the Davy Hotel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where the fugitive was taking mineral waters for his ailments. Although many accept this version, skeptics at the time and even today have observed that the train Tilghman and Doolin stepped off in Guthrie arrived from the north, not the east.

Whatever the circumstances of the arrest, Doolin spent the next seven months in the Guthrie jail, except for a day trip to Stillwater in which he was arraigned for his part in the Ingalls gunfight. Dynamite Dick Clifton joined him in Guthrie on June 22, but not for long. On July 5, Doolin and Clifton joined twelve other inmates in a successful jailbreak.

By most accounts, Doolin fled directly to Lawson (not Lawton), a hamlet in the southern environs of present-day Pawnee County and six miles west of Jennings, to visit his wife, Edith, who was staying there with her parents. Two months after his escape, on January 24, 1896, Doolin was killed there shortly after dusk by someone in the ten-man posse led by deputy U.S. marshal Heck Thomas.

Doolin was quietly leading his horse away from the Ellsworth house in the coming darkness, with his rifle in his other hand, when Thomas ordered him to surrender. Doolin began shooting toward Thomas instead, but he didn’t last long. At least sixteen bullets found their mark, leaving the outlaw Bill Doolin’s emaciated corpse staring into the distant nothingness.

And with that, all the principal members of the Doolin gang were dead except “Little” Bill Raidler, a part-timer who did his time in federal prison. While there, he was a friend of William Sydney Porter, who became the famed writer O. Henry. Raidler died a somewhat respectable citizen of Yale, Oklahoma, in about 1905. He lived about ten miles from Ingalls. Lucky for him that he’d joined the Doolin gang too late to be one of the combatants there.