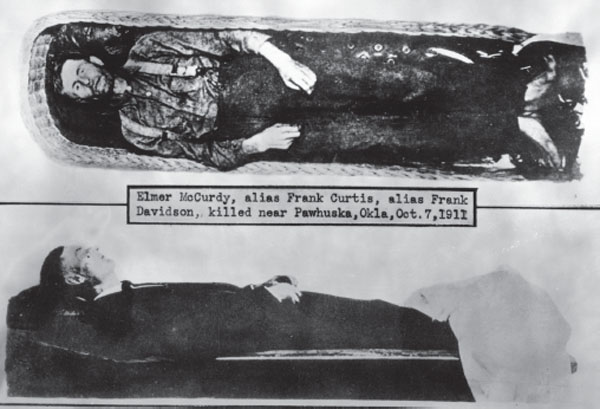

Elmer McCurdy. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

5

TERMINALLY DUMB

Most criminals are not mental giants; that’s why they’re criminals. Professor Moriarty of Sherlock Holmes fame was a wizard of fictional crime, but in the real world you are more likely to find clowns like these.

Even the experienced criminal is not immune to stupid. Take the fugitive Billy the Kid, who saw a shadowy figure in a small room and asked, “Quien es? ”(“Who is it?”), then absorbed Pat Garrett’s bullet by way of reply. Or the nitwits who pulled the Roy’s Branch train holdup near St. Joseph, Missouri, back in 1893. The three original members of the gang even recruited three more men for the job. Their mistake was taking the new guys at face value; one was a cop, and the other two were citizens working with the police.

When the three real outlaws pushed into the express car, they were surprised to find it inconveniently full of policemen, who promptly blew two of them away. The third gang member was wounded but got clear—until the next day. He asserted his innocence but convinced nobody. Not only were there three honest men to identify him for what he was, but he also had a bloody mess where three fingers used to be and a pocket full of cartridges to boot.

The dummkopf syndrome extended to both the famous and obscure alike. Sooner or later, they all did something stupid, which got them a ticket to a prison cell or the graveyard. Their ailment was about equal parts stupidity and arrogance.

Among the once famous oafs was George Birdwell, an experienced hoodlum, robber and killer. He was right arm to Charles Arthur Floyd, known to his friends as “Choc” and to the rest of the public as “Pretty Boy.” George should have known better than to take on the little bank in Boley, Oklahoma; in fact, Floyd warned him against it.

But Birdwell thought he knew better. So, with a couple other professional thugs, he drove into Boley one day late in 1932. Boley was a thriving allblack town, one of a number in Oklahoma; its citizens had taken careful precautions against bank robbery, the favorite crime of those days, for banks had been robbed within a few miles of Boley. The town stockpiled weapons, and the bank installed an alarm linked to other businesses.

The citizens of Boley were tough and prepared, but Birdwell helped them a lot. First, he chose a Saturday for his raid. Predictably, the town was full of farmers shopping, and the prairie chicken season had just opened, so many of the shoppers were buying shotgun ammunition as well as groceries.

Second, he left their getaway car parked facing away from their escape route, requiring the driver to back up and then make a U-turn to reach the highway and safety—all this when speed was of the essence. Also, since the car was parked with the driver’s side toward the bank, there was only one door to jump into when the time came to escape. There would have been two, had the car been parked facing the escape route, with the two passenger’s side doors toward the bank.

In the event, Birdwell was killed dead and so was the getaway car driver as he tried to manage his U-turn. The third thug was filled full of birdshot—as many as two hundred of them—and went off to prison.

Then there was Grat Dalton at Coffeyville, first piling up a sack full of a bank’s silver, a heap so heavy it was impossible for one man to move. Grat then stood around waiting for the vault to open, deceived by a young teller’s unctuous lie that the bank’s vault was locked. It wasn’t, of course, it being the middle of the business day.

But while Grat stood waiting for his cornucopia to open, the town’s two hardware stores were passing out weapons to the alerted citizenry right outside the door. One of the local folks shot Grat dead. Sic semper stupid.

Then there was Elmer McCurdy, who had all the brains of a doorknob. With some confederates, he pulled a two-bit robbery and then separated from the other hoodlums. Carrying his puny share of the loot, which included a couple demijohns of whiskey, he fled—on foot, his first stupid mistake. Perhaps to console himself about the lousy haul, he sampled the whiskey liberally as he walked until he was thoroughly spifflicated—error number two. Later, instead of going past a farm to put distance between himself and the posse, poor Elmer sought and received permission to spend the night in the barn—his third very bad idea.

Elmer McCurdy. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

When he awoke, Elmer was surrounded by the law. Summoned to surrender, he made error number four. He fought and, in the ensuing gunfight, came in a bad second.

In fairness, Elmer now began a far more successful second career. He became an exhibit first in the mortician’s emporium and then in a series of freak shows. Step right up, folks, only a quarter to see a real, dead outlaw. Finally, substantially the worse for wear by the ravages of the years, multiple coats of wax and luminous paint, he ended up as what he began: a dummy, or so it was thought when he was “discovered” in 1977 in a wax museum display in California during the filming of an episode of The Six Million Dollar Man television series. Soon thereafter, he was buried next to the infamous Oklahoma outlaw Bill Doolin.

Elmer’s extended second career was unusual, but he shares with other outlaws the common trait of paralysis of the brain. Cerebral density got him killed.

Alphonso Jennings was just as stupid, but he came from a good family, was the son of a judge, went to law school and became a lawyer himself, like several of his brothers. All went well until the day two of his brothers, Ed and John, got crossways with another lawyer in court. The other lawyer told one of the brothers he was grossly ignorant of the law—which he well may have been—and was called a liar in response. Tempers flared. The other lawyer was Temple Houston, son of Sam Houston of Texas. Temple was just as good with a gun as he was with a writ. Before meeting the Jennings boys in Woodward, Oklahoma Territory, he even bested Billy the Kid in a target shooting contest, or so it is said. The judge quelled the courtroom squabble in Woodward, but bitter feelings remained. And at the end of the day, the brothers found themselves in the Cabinet Saloon with Houston and a friend. The earlier courtroom quarrel led to a shootout in which the Jennings brothers came in a bad second. Ed was dead, such brains as he had running out a hole in his head. Al’s brother John was wounded and ran for his life.

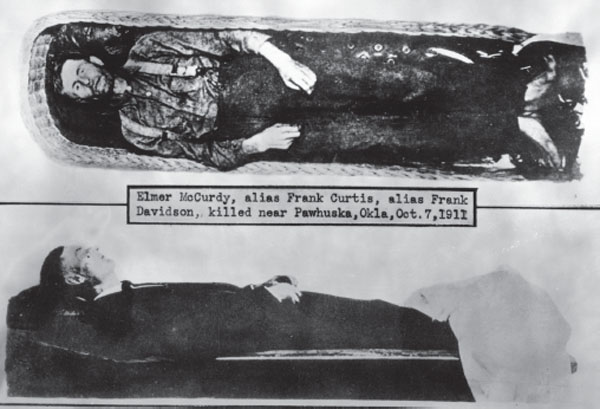

Al Jennings—big smoke, no fire. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

A jury decided the killing was in self-defense, there being solid evidence to that effect and some circumstantial evidence that the shot that killed Ed Jennings was the result of lousy marksmanship by his fleet-footed brother John. Al fulminated about the “perfidy” of the prosecution, loudly announcing that his brother had been shot by “sneaking and unseen” men in what amounted to an ambush.

This gave Al his big chance. Threatening bloody vengeance on his brother’s killer, he found it convenient to turn outlaw at the same time. Oddly, though Houston was well known and easy to find, Al never seemed to be quite able to arrange to be at the same place Houston was. Instead, he went off a-robbing and found it most unprofitable, mostly because he was inept to a degree far exceeding the average, even among outlaws. A prolific and knowledgeable western writer dubbed him the “Clown Prince of Oklahoma Train Robbers.” The title fits Al precisely.

He started his dubious career in crime in 1896, forming a gang with still another brother named Frank, a couple of nonentities called the O’Malley brothers and Little Dick West, a real outlaw. They frequented the almost lawless country along the South Canadian River, robbing little stores and saloons and attempting the occasional train.

They had a few successes, like the post office they hit for some $700, but most of their crimes were busts, like the train they tried to stop by stacking ties on the tracks and setting fire to them. The engineer charged the obstacle, filling the air with flaming ties, and pushed on through.

That was less embarrassing than getting a train stopped and blasting its safe, only to discover that two successive charges of dynamite couldn’t dent it. They had a repeat performance with another train safe, also tougher than both them and their dynamite. During one of these abortive attempts, clever Al successfully knocked off his own mask.

Al’s big strike, the bonanza all criminals dream of, also fell flat. The train was supposed to be carrying almost $100,000, but again Al found a safe impervious to dynamite. Robbing the passengers yielded the robbers only four or five dollars each. That tore it for Little Dick West. He’d had enough of running with idiots and would operate elsewhere until he perished at the hands of a posse in 1898.

The gang, all wounded, soon fell before a posse. Al got five years, only to emerge, get himself readmitted to the bar and run first for county attorney in Oklahoma City and then for state governor. Fortunately, he was unsuccessful. Still full of noisy bravado, he tried his hand at Hollywood, where he dabbled in films, posed for photos with all sorts of cowboy actors and celebrities and otherwise made an ass of himself.

He won a measure of fame with a book called Beating Back and then produced a movie of the same name. The film was a wild congeries of half truths and downright inventions. Emmett Dalton saw the thing and commented, “I had one hell of a good laugh.”

Still, Al was content. After all, he was a legend in his own mind.

That brings us to the other Oklahoma outlaw bearing the same first name. Al Spencer was born into a respectable family but didn’t share their morality. He did three prison stretches for cattle rustling, burglary and sticking up a local postmaster as that gentleman walked home from a poker game.

Al didn’t learn a thing. After escaping from prison, he went right back to crime, this time working with other bad hats robbing small banks in Oklahoma, Kansas and Arkansas. Their biggest payday was a Kansas jewelry store, where they looted some $20,000 ($274,000 today) in watches and jewelry. That had its own hazards, of course, because for loot like that you have to find a reliable fence, which took a huge cut of your profit.

Along the way, Al further demonstrated his intellectual poverty by driving around with a jug of nitroglycerine on the running board of the car, covered with a blanket. Discovering that for some reason the blanket had caught fire, he disposed of the nitro, miraculously without an explosion.

Al became the Typhoid Mary of his own gang. The members one by one became prisoners of the law, either dead or wounded. Three of them, including Al, escaped one ambush only by abandoning their car and fleeing on horses they had stashed. Between jobs, they sought refuge in the wild country of Oklahoma’s Osage Hills but didn’t have the sense to stay there. During their sabbatical, they held up the post office in Pawhuska and tried to dynamite the safe. A mighty explosion produced absolutely no effect on the safe except totally jamming its door. No money—again.

And they had killed two men, one of them for nothing at all. “You ignorant bastard! You’ve killed two innocent men, and now there’ll be hell to pay,” said one of their female “companions.”

There was. Most of the gang ended up in the hands of the law, some of them shot, one so badly that he lost a leg to amputation. Unperturbed and reinforced with new recruits, Al took on another train, said to be carrying some $20,000 in Liberty Bonds. They also got some of the passengers’ cash and a paltry amount from the express car safe.

Al supposedly claimed he could protect himself from fingerprint identification by wearing rubber fingerstalls (protective coverings used for injured fingers) while he “worked,” if that’s the word. The idea is also credited to one of his gang, an oaf named Ike Ogg. Whoever thought it up, the law sensibly asked around to see who had been buying lots of fingerstalls. Ogg eventually rolled over on his confederates.

No matter how lucky you are, you can do only so many stupid things without getting caught. The end for fumbling Al Spencer came on a September night on a bridge along the Oklahoma-Kansas border. A posse waited in ambush as Al committed his final stupidity. Summoned to surrender, he fired into the darkness and, in return, was punctured eight times, going from terminal dumb to terminal dead. Nobody missed him much. The survivors of his gang were either sent to prison or killed by the law, save for one who beat his wife so often that she finally filled him full of holes.

Finally, consider Dave Rudabaugh, who rejoiced in the sobriquet “Dirty Dave,” a reference to his permanent and penetrating stench. His personality was just as rank. He robbed people, killed people, rolled over on his companions to save himself and, at various times, ran with some of the worst outlaws, including the Cowboy faction of Tombstone fame and the Las Vegas, New Mexico cabal of Hoodoo Brown.

Dave ultimately took his foul smell and vicious ways down to Mexico when the United States became just too hot for him. He inflicted himself on a fair town called Parral, down in Chihuahua.

Disappointed in a card game in the local cantina, he killed a couple of the locals—not a smart idea for a smelly gringo stranger.

The cantina loungeabouts vamoosed at a high lope. Dave soon departed himself, since there was nobody left—alive—to play cards with. Trouble was, he couldn’t find his horse. And then Dirty Dave showed just how bright he was: he went back inside the cantina only to find much of the town waiting for him.

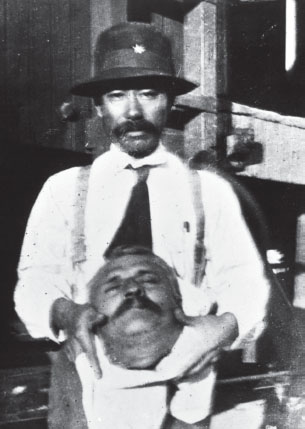

A rurale holding the remains of “Dirty Dave” Rudabaugh. Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries .

Dave had worn out his welcome in Parral; the locals not only ushered him into the next world but also removed his head, droopy mustache and all. They left his hat on top and paraded the head around town impaled on a pole, making a sort of fiesta.

It was about the only time Dirty Dave brought other people pleasure.