CHAPTER 6: THE ENTERPRISE JOURNEY TO INTELLIGENT AUTOMATION

Intelligent automation stages

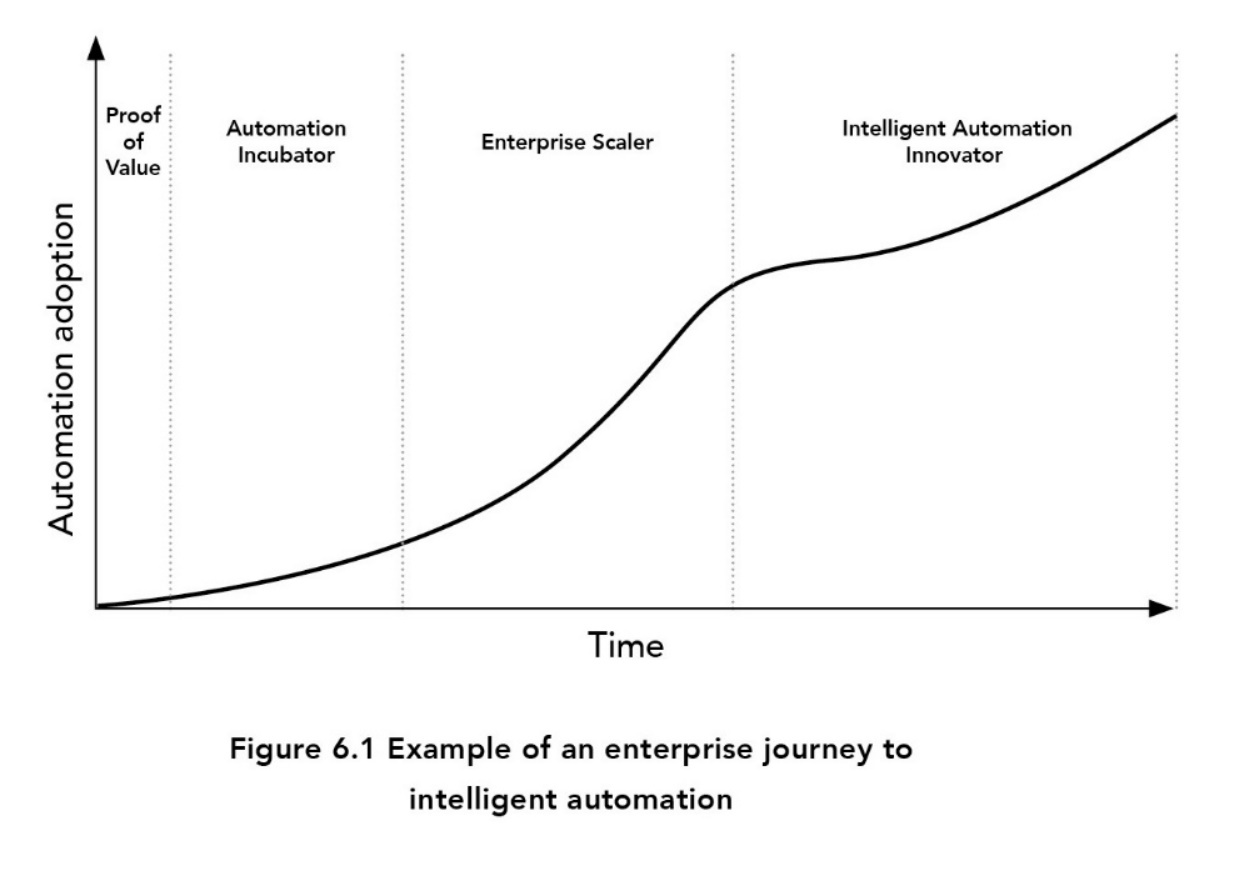

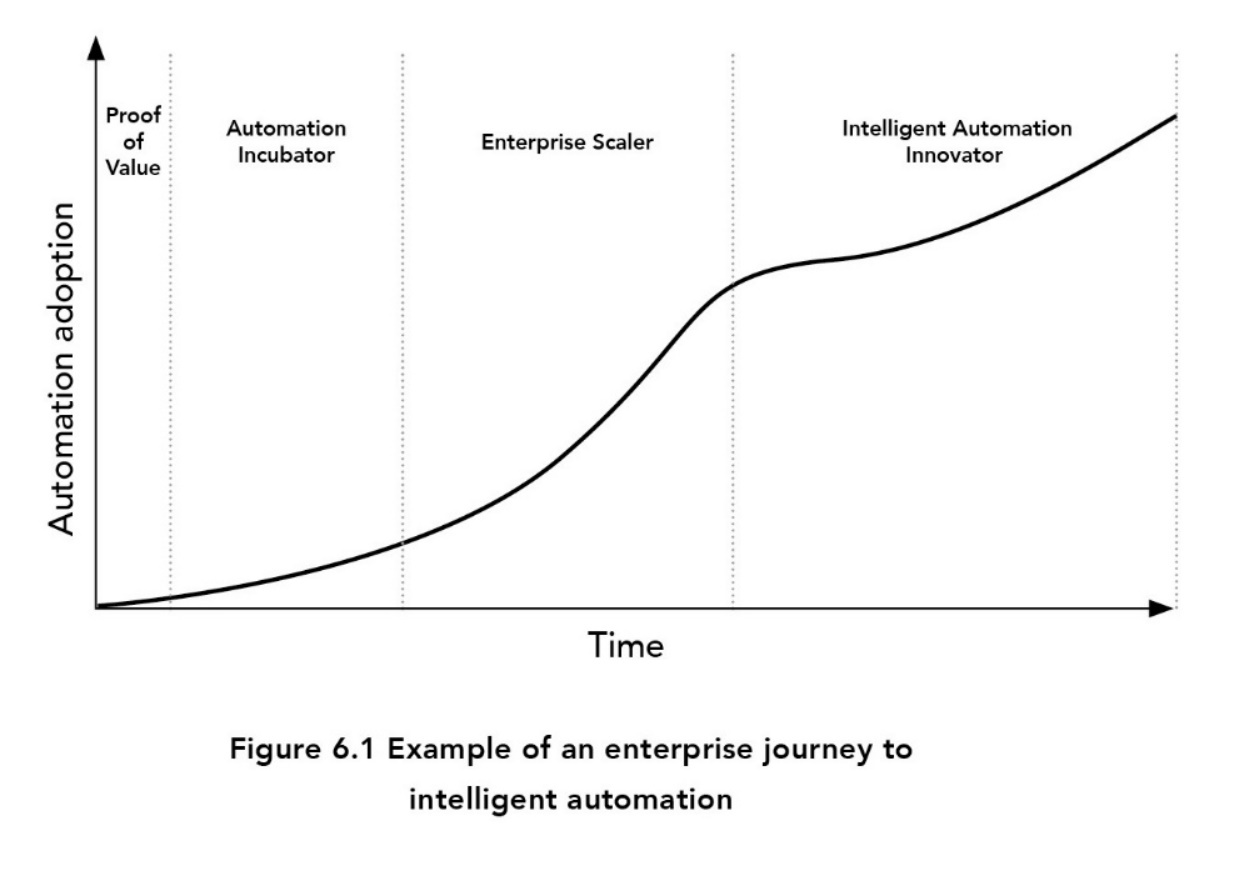

The automated enterprise journey maps the organization’s maturing automation capability from a company technology incubator to becoming a key enabler of the business strategy and transformation initiative. The journey is reflected through a series of stages that have been adopted by most organizations to date: building an automation RPA capability first, then scaling and complementing with cognitive technologies that intelligent automation can offer.

For each stage, we highlight the key objectives, both facilitating the initiation of the journey and providing visibility of what lies ahead to support forward planning. While each stage has been presented sequentially, the rapid maturity of RPA automation and the rise of intelligent automation provides organizations with more opportunities for how to traverse this journey. They could adopt intelligent automation jointly with enterprise scaling or move from the incubation stage directly to some level of intelligent automation. Like learning to play tennis, we each come to the court with different genetic make-ups, body types, and motivations, yet we still need to learn core fundamentals such as hand-eye coordination, foot movement, and racket grip before we can even attempt an elegant serve.

The ideal path and challenges encountered along the journey will depend on several factors such as the capabilities of your team, the ability of the organization to manage change, and the level of sponsorship within the enterprise, to name but a few. Some organizations may find staying longer in a particular stage is important to solidify certain capabilities, such as their delivery model or engagement approach. Only by understanding the core competencies within the organization and the expectations of each

stage is it feasible to define the right approach. Each path is unique and so defining your own automation journey will be key.

As shown by figure 6.1

the key stages of the journey towards intelligent automation are:

- Proof of Value

- Accelerated Incubator

- Enterprise Scaler

- Intelligent Automation Innovator.

Proof of Value stage

The key objectives of the Proof of Value stage are:

- Create a demonstrable proof of value that resonates with key stakeholders

- Understand the key steps to successfully implement your first automation

- Understand automation technology and the partner landscape

to support your journey

- Formalize support to establish an automation capability.

Identifying inspiring use cases

At this initial stage, there may be no or several potential candidate proof-of-value opportunities identified to automate. The selected use case to automate needs to demonstrate an ability to provide immediate benefit while being relatively simple to develop.

The Proof of Value stage should not be used to set expectations on average build durations, as typically the build will have taken many shortcuts such as in configuration standards and approaches to error handling. The proof of value needs to automate with the senior stakeholders in mind by understanding some of the key challenge areas in the business, such as cost or quality. Rather than walking away with the COO’s top five issues to resolve, at this entry level, it is about identifying an opportunity to demonstrate how an ongoing business challenge can be immediately resolved by applying basic automation in the form of RPA.

Once the automation has been developed, a short video comparing the process being executed manually alongside the digital worker executing the process can both communicate the obvious benefits such as time, speed, and quality and bring to life how automation technology works at a high level.

Presented effectively, this can be the “eureka” moment when key stakeholders understand the potential for automation. A demonstration of even a simple automation can help them grasp the wider potential in their respective functions to add benefits, resolve key business challenges, and innovate to support their functional goals.

Understanding the technology and partner ecosystem

The intelligent automation software market continues to expand rapidly, making it currently the fastest-growing segment of the enterprise software market. Significant automation product company valuations have created an increased number of new

entrants, with many overlapping functionalities creating a difficult landscape to navigate product selection and comparisons for many customers. The extension of RPA product technology solutions to encompass cognitive-based capabilities, typically through a combination of proprietary in-house developments and third-party partnerships, has further complicated the process of technology selection.

Systems integrators and consultancies have also benefited significantly from this market growth and in many cases have entered into strategic partnerships and alliances with varying complementary product vendors. This places them in a unique position to provide a level of knowledge on these emerging technological toolsets, their key features and interoperabilities, while being able to share common experiences and use cases in similar industry sectors.

While many of the established IT service providers and consultancies have continued to grow their automation and cognitive practices, there has also been a growing emergence of niche providers. These have varying value propositions, such as deep knowledge of financial business processes or specific expertise in the application of automation to particular industries such as insurance services.

At this initial stage, the objective should be to scan the market to understand the core features and differences in automation technology. This provides an invaluable opportunity for your organization’s IT function and sponsoring business function to work collaboratively to review market offerings and collectively select the right technology to meet the needs of the enterprise.

Given the wide variability in solution functionalities and architectures alongside key factors such as ease of use, cost, and cognitive features, the proof of value should ideally aim to automate the same process with at least two competing product offerings. Even in a short period of time, it should be possible to build a proof of value and this will serve to considerably improve your organization’s knowledge of the technologies and the variances that may occur.

Organizations such as HFS

[61]

and Gartner

[62]

can provide valuable market research, insight, and advisory services on the various product vendors, systems integrators, and consultancies, providing information on the market positioning and product differentiation based on their deep understanding of these emerging technologies over the last few years.

Understanding the delivery process

The Proof of Value stage should not only be used to demonstrate the technology but also provide an opportunity for the team to observe the key steps required in automating a business process. Rather than working with the selected automation product or third-party vendors to simply outsource the build of the digital worker, this early engagement should be used to understand the delivery steps, from process capture and design to build cycles. This will not only highlight your potential partners’ robust delivery methodology but also enable you to consider how the delivery approach can be adopted internally. There may be skills gaps such as the availability of skilled automation business analysts, or dependencies on functions such as IT to host the automation platform or support a cloud-based solution.

A successfully completed proof of value should identify the right automation technology, provide a strong level of understanding of what the end-to-end automation lifecycle process is, and create demonstrable content that will engage and stimulate senior influencers. This should aim to generate the appropriate level of support to approve a business case that either formalizes the setup of an automation capability or provides the necessary backing for a more piecemeal approach to automating processes in the enterprise.

Proof of Value stage checklist

- Identify inspiring use case(s) with key stakeholders to trial a proof of value

- Initiate comparative analysis on competing automation technologies and solution partners

- Understand the automation delivery process and how it could be applied internally

- Develop some early communication collateral which showpieces the completed automation

- Secure early senior stakeholder support to mobilize an automation capability.

Accelerated Incubator stage

The key objectives of the Accelerated Incubator stage are to:

- Create a foundational operational automation capability

- Set up a supporting PMO (Project Management Office) to track and manage performance

- Build a high-performance team

- Establish the automation technology platform and supporting partners

- Engage stakeholders to generate awareness and build an automation backlog.

At this point, following the successful delivery of the Proof of Value stage, you should have secured senior buy-in that either formalizes the setup of an automation capability or supports a more piecemeal approach to automating processes within your business. The two key outcomes of this critical early phase of the accelerated automation incubator are credibility and enterprise feasibility.

Firstly, over the early phases of this stage, the automation initiative needs to establish it can successfully identify, build, and manage digital workers that deliver value. Secondly, and more towards the latter part of this stage, the program needs to determine the feasibility

of an enterprise capability by generating and identifying potentially wider demand.

Establishing funding and governance

The initial funding model of the program is an important consideration since it is likely to directly impact the level of enthusiasm that is generated by potential internal customers. Given the likelihood that the scope of the capability at this stage is within a specific function, such as operations or finance, organizations typically adopt a business vertical-sponsored funding initiative.

The supporting benefits management model should also seek to

confirm what constitutes viable benefits, such as employee capacity contribution, and aim to validate the internal process for the approval of benefits prior to starting an automation project.

Establishing governance at the outset will provide the program with clarity of purpose, robustness through structure, and legitimacy. What it should not do at this stage is to add layers of corporate bureaucracy to compromise the flexibility required, risking the success of the program during this formative stage. A governance framework should help define the purpose of the sessions, attendees, and frequency, from weekly reviews that focus on the operational performance of the capability to formal reviews with divisional heads.

Steering committees need to collate internal senior sponsors from business and IT and external partners to drive a start-up mentality of open, transparent communications focused on unblocking issues and accelerating performance. For organizations without the experience of growing innovation incubators, the right governance framework and approach has the opportunity to demonstrate the potential impact of creating a digital start-up style.

Delivering the first digital workers

The first set of automation projects need to match the formative skills of the new automation teams by trading off the potential allure of high-benefit, highly complex projects for low complexity “as-is” process automations. This should focus on delivering a carefully selected set of projects that demonstrate the ease in automating existing processes that may be labor-intensive, mundane, or prone to errors.

While reducing the associated delivery risks of time, quality, and cost due to their low complexity, these early automation projects should resonate with the business as an initial set of use cases that demonstrate how automation can easily be applied to support functional goals.

These important use cases should be secured through top-down senior management efforts, ensuring a collaborative role between the business and the new automation capability. The relationship

between the senior stakeholders and the automation capability sponsor should be honest about the developing nature of the capability, acknowledging that teething issues will undoubtedly occur for early adopters but that the delivery team will have commitments from senior management.

Setting up your capability to provide data-driven performance information will be key to monitoring actual against required performance. Following the delivery of an initial batch of automation projects, key metrics such as capability velocity can be baselined and iteratively reviewed following improvements made across the automation project lifecycle. As an example, a business-to-business reseller of IT equipment across Europe and North America started its automation journey with initial sponsorship from its finance function. Having initially automated three processes across finance accounting, the team progressed to target some additional financial activities for automation.

Performance reporting highlighted that end-to-end automation project velocities, from starting an IPA to delivering a digital worker, were taking a lot longer than originally expected. Deeper analysis showed that a greater amount of time was being spent during the stages of PDD and at the end of the build development cycles. Working with its development partner, the team identified one of the key reasons for these elongated time frames. Subject matter experts in the business were not aware of the time required from them during the process analysis and build stages, when the automation analysts and development team would typically schedule review sessions with the business. This meant multiple meetings were required with business process experts based on their availability, which in turn took longer.

Armed with this insight, the automation capability decided to update its supporting change impact process to include sharing detailed expectations from the business. During an initial business kick-off session, prior to entering into the detailed design stage, business process subject matter experts would be briefed on the level of time investment typically required from the business and given a supporting high-level time-plan. These refinements both

improved the automation project velocity performance times and supported the creation of a stronger working relationship between the automation team and the business.

The early introduction of a performance management capability will both support the development of critical analytical skills to use data to provide insight and drive change and help to establish a performance-driven team.

Forming a high-performance team

The setup of the initial automation team at this formative stage of the capability is recognized as one of the key periods within which to create a sustainable, high-performing team. It’s important to establish key factors for success, including cooperation, commitment, ownership, and goal setting.

[63]

Formally kicking off the initiative and holding regular review sessions at the automation team level and functional team level (such as developer reviews) can assist to communicate important direction-setting goals at the onset, and establish an open and supportive team culture.

Targeting less complex automations initially will help the right team structure to evolve, given that team members may vary in their levels of technical expertise. For example, senior automation developers supporting the professional growth of more junior members. Supported by the organizational structure and working practices (such as adopting agile) but shaped by the team, the emerging internal automation team culture needs to be able to quickly adapt to a steep learning curve. The team will need to balance resources that will vary in skill sets and may accommodate a mix of employment types, such as employees, external consultants, and potentially independent contractors, directing all team members to create a unified, high-performance unit.

The automation capability needs to be able to rapidly develop the necessary knowledge of business processes that exist across the organization and the associated work that is conducted in the business divisions. An agreed temporary assignment or job rotation with business process analysts from specific business divisions to the automation capability may, in the short term, be an easy way to

facilitate the transfer of this tacit knowledge. As well as helping to facilitate knowledge of the business processes themselves, this should help the automation capability to understand key relationships in the business division and share any specific cultural ways of working.

Although many organizations have yet to scale their capabilities successfully, the automation delivery lifecycle processes that support the development of simpler, lower-volume automation projects are relatively well understood. Rather than creating fundamentally new delivery processes to support the automation factory, the embryonic capability should be using knowledge from experienced team members and partners to understand which parts of the automation project lifecycle work well, superimposed with knowledge of the organization. The accelerated growth of the automation factory will stress-test the automation project lifecycle model at various times. A mindset of continuous review and refinement should help to ensure the efficient utilization of resources and reduce key project bottlenecks.

This formative stage of the incubator accelerator provides an early window for a culture to be curated that is both cognizant of the wider organization and unique, principled, and engaging enough to drive through the various challenges encountered across the current and future maturity stages.

Initiating technology and partners

The automation technology selected would have been informed from reviews and analysis conducted during the Proof of Value stage in conjunction with IT. One of the key challenges for many organizations in selecting an automation technology solution is balancing the need for a solution that can provide the basic level of automation through RPA today with the capability of complementing it with more intelligent automation technologies both now and into the future.

IT will also inform the preferred deployment model of the solution, such as enterprise-hosted, SaaS (software as a service), or cloud. Cloud-based solutions, to which many organizations are

migrating, will continue to provide richer technological features but may be impacted by enterprise and governmental data regulations such as GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Whichever approach is adopted, the requirement will be to have an automation platform that has been fully tested and able to support the development of the digital workforce.

Following the selection of the core automation technology, the supporting partner strategy to adopt is a key consideration and will directly impact the design and skill levels of the emerging automation capability. The Proof of Value stage should have helped to create a good level of understanding of the skill sets required to support the end-to-end delivery lifecycle of an automation project. Complementing this knowledge with the availability of internal resources, such as business analysts and automation developers, should then support the development of your partner strategy.

The growing ecosystem of specialist partners has provided an array of services to support the successful growth of your automation capability, from business process discovery through automation development to in-life digital worker support. At this stage, you may have underestimated the skills required or the demand for automation projects that may exist, so adopting a flexible relationship with partners will help de-risk the program and manage costs.

The automation operating model can then be designed collaboratively based on the services selected with partners. For example, a medium-sized financial services company selected a third-party partner to develop, test, and release all its identified process automations. The operating model and supporting commercial contract defined a key list of roles and responsibilities between the client and supplier, with the client being responsible for the provision of automation project PDDs and each one requiring a sign-off by both parties. This resulted in high-quality design documents being issued by the automation capability. Consequently, the estimates of effort and delivery timelines provided by the supplier were accurate.

Establishing an engagement strategy

Following the successful, albeit challenging, delivery of an initial batch of selected automation projects, these will then serve as real use cases to drive further functional opportunities by supporting the formalized engagement strategy. The strategy drives top-down enthusiasm by reaching out to heads of departments, influential functional leads, and their operational teams. A detailed organizational chart, along with management contact details, allows the creation of a list of contacts to reach out to, either through 1:1 engagement sessions or requests for agenda slots in their regular team meetings.

The engagement sessions themselves should support the execution of a clearly defined communications strategy, adopting the automation culture framework in chapter 5 to educate the business on the digital workforce and emerging automation technologies, sharing the capability that has been invested in internally and how it can help them. These sessions provide a unique opportunity to energize parts of the organization and initiate them on the emergence of the future of work.

The content needs to focus on the why, what, and how of automation, supported with specific industry challenges, and demo recent internal use cases that the department or team can directly relate to. Depending on the numbers of attendees, sessions that are facilitated as two-way conversations, rather than automation being seen as something that is being “done” to them, will reduce the perception of automation as a threat. It will support a much richer dialogue and help generate unique insights on the challenges faced by both the function and the team.

Leveraging, where possible, emerging automation advocates who have been through the automation project lifecycle experience and had their digital workers recently deployed, can act as an incredibly powerful voice. The objective is to exceed the expectations of your internal customers to create your automation evangelists.

Accelerated Incubator stage checklist

- Agree program funding, business plan, and benefits management

approach

- Establish a PMO and a data-driven performance management capability

- Initiate and nurture the automation team

- Select and build the automation technology platform

- Select and agree working practices with partners

- Define and develop the automation project lifecycle model

- Demonstrate delivery of value with each automation project

- Create communications content and establish an engagement strategy

- Start building a delivery backlog of automation projects

- Initiate a support control room capability

- Secure senior stakeholder buy-in to grow the automation capability.

Enterprise Scaler stage

The key objectives of the Enterprise Scaler stage are to:

- Extend your communications strategy to support enterprise-wide engagement

- Mature your delivery processes to support scale

- Establish delivery governance across multiple enterprise functions

- Identify intelligent automation complementary technology partners and successfully execute localized proofs of value

- Align to the corporate level challenges and digital transformational strategy

- Actively promote performance to board level.

By now, the automation incubator project should have started to generate some interest across the wider organization, due to its ability to demonstrate a refreshing agility and capability not seen in the organization before and deliver near-immediate benefits that are both tangible and visible.

While typically still constrained to a specific business function, the early adoption of the capability and its positive impact on his or her business provides the C-level within the function with ultimate board-level “bragging rights.” They are now the most senior

advocate of the capability and a key board-level influencer to support the case for the automated enterprise. This should create the momentum to drive the extension of the capability across the organization to increase its ability to solve a greater number of business challenges, automate a wider reach of processes, and ultimately deliver more business value.

Developing an aligned scaling automation strategy

The automation strategy should now demonstrate a cohesive alignment to the corporate strategy, which may be through the use of automation and cognitive technologies to support value creation or drive cost leadership, or by directly enabling the digital transformation initiative. The Intelligent Automation Maturity Framework will provide a view of the current maturity of the capability, but critically will now act as the navigational aid to support the growth of the automated enterprise and its movement along the benefit’s trajectory.

Typically, following the successful delivery of the Accelerated Incubator stage, organizations have two key strategic options to move forward with: transitioning to scaling the enterprise capability or delivery of a smaller number of higher value automation projects.

Scaling the automation capability is about doing more of the same, except across the expanse of the enterprise with an increased volume of automation projects. This will constitute automating business processes “as-is” and adopting some level of digitalization across the automation projects delivered. The adoption of this strategy needs to be predicated on the basis that there are a significant number of automation projects that can deliver value to the organization. This may be based on the current backlog of projects or estimates based on current engagement conversion rates and the number of functions or teams that have yet to be engaged with.

For example, following year one into its automation CoE, a large petrochemicals company based in Malaysia delivered over 36 automation projects, providing a return on investment of over 160%

in the first year. Given that the majority of the projects delivered were in the finance function, the company was able to conservatively estimate a doubling in demand over year two, given that its operations and global marketing business lines had yet to be introduced to automation.

Challenges of enterprise scaling

The transition from an accelerated incubator to enterprise scaler represents one of the most challenging stages in the maturity of the automation capability. Nonetheless, it is no different to the classic pain points identified when many large corporates look to scale an internal incubator.

Large organizations require technology to function at an enterprise level so the benefits of IT investments can be distributed more widely and leverage economies of scale. However, successfully scaling the capability has been seen as a key challenge to the burgeoning automation industry over the last two years. Deloitte, a leading global consultancy, highlights that only 3% of organizations have successfully scaled their automation capabilities in order to serve the wider enterprise.

[64]

As well as presenting a major issue for organizations, this also presents an issue to automation software product vendors, who critically need to be able demonstrate the ability for automation to drive greater benefits within the same customers.

While enterprise-wide scaling does present a number of challenges, some organizations have been able to successfully navigate the journey and transition their automation capability from an incubation experiment to one of the key technologies that can help support the digital transformation agenda.

There are three key common sources of demand tension when transitioning to an enterprise capability.

Firstly, the opportunity to increase the volume of projects through increased access to other business functions will demand changes to the automation capability’s underlying structure, which may previously have been highly centralized through a CoE. This emerging automation capability will now need to successfully

engage across different, often siloed, business units to satisfy their varying and sometimes competing agendas without compromising key performance targets such as automation project velocity and quality of deliverables.

Secondly, the demand for automation solutions increases not only the volume of automation projects but also the complexity of the projects as the capability attempts to leverage the now enterprise-wide scope to automate greater breadths of the end-to-end processes. This move to digitalization as well as digitization will typically require business processes to be improved and optimized prior to automating. This will place the automation capability onto a new learning curve as it develops the necessary skills and competencies to understand, analyze, and automate more complex work activities.

Finally, these external demands in turn require an ongoing sequence of incremental, fine-tuned changes to the automation team to reorganize its size and structure without impacting performance.

With the successful delivery of a number of automations and the growing recognition of the potential impact of the technology, defining the automation strategy is key in order to harness the ambitious demands across the wider enterprise. With regard to benefits, this may include revisions to the benefits management process and new thresholds on the minimum return on investment criteria for an automation project. The central finance function should help in aligning the required changes to corporate best practice, providing greater integrity and accountability during events like benefits audits.

The new business case or performance targets for the evolving automation capability typically will need to be agreed. Extrapolating, as before, the expected number of projects that can be delivered within the time frames and the supporting benefit contributions based on the revised “project mix”, alongside increased costs of licenses and platform hardening costs, should all support in the creation of the new business plan. “Be careful what you ask for” is the adage here, as success is a double-edged sword. Over-delivery of an initial automation business case is common,

given the nature of automation projects. But it should not lead to setting unrealistic expectations for developing the more complex enterprise-wide capability.

Designing the automation capability for scale

The revised enterprise-wide mandate will need changes to the structure of the new capability. These will be required both to support the increased demands of more internal customers and increase the delivery resource capacity in line with growth estimates. The optimal type of organizational design at this stage will vary for different enterprises as it will depend on a number of factors, such as the existing organizational structure, program funding structure, and changes to partnership relationships.

While it has been common at this point for many enterprises to adopt the Center of Excellence or decentralized design models, a number of other options exist, such as rolling the toolset into a group-wide operational excellence or business process improvement team. Each organization design option will have certain advantages but will introduce new complexities that may need addressing. For example, extending the remit of a business process improvement capability to provide automation may require retraining business analyst resources in process automation and business process redesigns as opposed to purely optimizations.

The use of Centers of Excellence as drivers of change in organizations should be challenged. The term has been used excessively in organizations over the last decade and they are guilty of a reputation of increasing bureaucracy. In many cases, they have become heavily centralized, highly skilled resource silos, driven by conflicting agendas.

Finally, the structure will be heavily influenced by the role of partners within the automation services industry. The global pandemic has dramatically removed many pre-conceptions related to remote working, significantly increasing the feasibility of offshored, near-shored, and outsourced models. Structuring the automation project lifecycle across lines of responsibility, for example, with a supplier responsible for automation build and

testing, provides organizations with an array of options that can enable scaling through different commercial arrangements with third-party providers.

For example, a leading European bank adopted a centralized–offshore model to scale its automation practice. The centralized team consisted of business analysts, first-line support controllers, and importantly, developers who were responsible for building the business process components of the automation solutions.

The organization’s IT partner provided an offshore resource center with additional development resources skilled in building business process objects, with the flexibility to ramp the team up and down based on changes in demand. Countries like India with a strong heritage of IT services, including software development, have seen a tremendous increase in IT professionals and students skilled in intelligent automation technologies such as RPA and AI. This provides access to skilled resources at lower costs. With experience in supporting organizations to adopt and grow their automation capabilities, the third parties you select should be able to provide valuable guidance on structuring the capability to perform at scale while managing risks and costs.

Scaling the performing team

As the automation capability transitions to support enterprise-wide scale and complexity, ensuring the ongoing performance of the team will be crucial. A larger number of resources, with differing skills and expertise and potentially more geographically dispersed, will require more integrative mechanisms to support team cohesion. The demand of business functions for greater support to develop their respective digital workers may push towards a more decentralized operating model. This can add layers of separation between functional automation teams and the centralized unit. Middle grounds may include the allocation of fixed resources and capacity to the functions.

Maintaining or improving the performance of the team at this critical point of transition between incubator and large-scale factory will require increased communication and alignment of the

individual, team, and capability objectives.

A start-up automation capability with a multinational global travel group used weekly team meetings to share key data-driven performance metrics across the end-to-end automation project lifecycle, such as the number of projects currently in a PDD stage, the number of automation projects in the build backlog, and the number of projects currently being developed.

As the capability scaled to serve more functions, the team size grew and management identified the need for additional discipline-oriented team meetings. This was initially trialed with the business analysts and the meetings were supported with more granular data relevant to those resource specialists, such as the average duration of a project when in the PDD stage and the number of opportunities in a pre-assessment stage. This drove discussion of how the business analyst team could improve its collective performance to increase the number of projects to the development backlog while consistently improving quality.

An enterprise-wide automation Center of Excellence for a global banking institution, working collaboratively with its automation services delivery partner, developed a pod delivery model. Each delivery pod consisted of two onsite business analysts, six offshored automation developers, and one test resource, providing a self-contained unit of capacity. As the capability grew across the organization, additional delivery pods were added to deal with increased demand for more capacity.

Analysis conducted on team performance data supported the development of key pod benchmark metrics, such as the expected number of completed PDDs per month and the expected number of automation projects delivered. Following the introduction of the pod model, performance data indicated that the pods were performing poorly. Internal reviews highlighted that the teams were going through a similar forming period as during the incubator stage.

In order to address the performance concerns and facilitate greater pod teamwork, management introduced a positive, fun-driven pod competition. Every month, specific pods were

recognized for achievement through a team event and, importantly, they shared what changes they had made to improve performance. A “monkey pod of the month” was also awarded to the worst-performing team, but in a fun way that allowed the team to equally share their lessons learned. Early feedback suggested there had been a marked increase in the overall capabilities’ performance, but also improved levels of engagement and collaboration across all the resources.

Moving to enterprise-grade governance

A transition towards serving the wider enterprise typically means engaging with a number of competing business divisions. With automation successfully recognized as an important technological enabler, changes to the automation capability structure will need to lean on greater levels of governance. In a CoE structure, for example, asking your senior sponsor to tell the CFO that the COO’s automation project is a greater priority can be especially career-limiting. Clear governance ramped up in line with the complexity of the organization should support in maintaining the ongoing integrity of the automation capability.

Changes to governance should provide clarity on factors such as benefit thresholds for automation projects, enablement of value-seeking initiatives that drive customer satisfaction, and—as was the case following the COVID-19 pandemic—business-prioritized projects that focus on the delivery of rapid tactical solutions. A clear understanding of the “rules of the game” helps communicate a level playing field and allow the growing automation capability to openly share which project opportunities are being progressed from other functions and importantly why, driving a sense of awareness and healthy competition.

Larger corporates will typically expect summarized updates on the progress of the automation capability at the business divisional level. Regular governance forums at the business division level sponsored by management can be set up with the joint purpose of maximizing the value that the automation enterprise capability can contribute towards the goals of the function. The terms of reference should include updates on the performance of the existing digital

workforce, removal of key blockers on projects currently in flight, and the identification and prioritization of new automation opportunities. The governance forums should drive a collaborative working relationship between the enterprise automation capability and business line management teams so as to progress their shared contributions towards the overarching business strategy.

The automation capability will also need to be plugged into the various BAU (business as usual) forums, such as function-specific change boards, and importantly IT review forums. With automation legitimized as one of the many technological solutions that can help solve the myriad of challenges across the organization, key roles within the IT function, such as solution architects and technical analysts, should be trained to develop an awareness of intelligent automation technologies. That way, they can develop a good understanding of what the suite of technologies can offer, and where they can best be applied—and equally where automation should not be applied.

Automation should then be one of the list of many technologies or approaches that IT and business process experts can review alongside more traditional solutions such as integration development or business process redesign. Its ability to solve business challenges with speed, agility, and lower costs should be coupled with its ability to create temporary or semi-permanent solutions that can be hardened to support more complex change roadmaps.

To scale automation across its business, the IT department of an Asian-based manufacturer of home and industrial refrigeration units included automation technology in its preferred IT-managed list of recognized solution options. A few months later, a request for changes to its in-house inventory IT system was raised by the business team. This specifically identified the requirement for additional reporting capabilities to improve current levels of stock-related working capital. Following the change impact assessment process, three potential options were identified by the IT change team: custom development, the incremental addition of employee headcount to manually process the reports, or automation of the

process.

An automated solution was assessed as the preferred option based on the cost and time to implement. Also, since the legacy inventory system was due for retirement in 24 months, the change would provide minimal impact to business operations while delivering acceptable returns within the time frame, albeit recognizing the solution would have a limited lifespan.

Organization-wide engagement

The automation project pipeline should have a healthy volume of automation projects now in the backlog “to-do” lists, or else there should be a growing list of engagements yet to conduct. A greater awareness across the enterprise on the applicability and benefits of automation, reinforced by the growing list of use cases, should support new automation opportunities to be identified from a growing number of sources in the organization.

The focus on internal customer service excellence and delivering on previous promises should create a wave of organic growth from existing stakeholders, as teams with digital workers think of new, exciting, and innovative ways to extend automation further into their functions to change the way they work. The updated engagement approach within the automation strategy should define the rationale to be applied with respect to what functions to reach out to. This can be driven by a number of factors, such as known pain points in certain parts of the organization, analysis conducted on headcount numbers per function, and simply relationships between senior stakeholders.

It can also involve reaching out to parts of the organization that are typically known as adopters of automation or holders of large third-party outsourced budgets, like back-office finance or business operations. This should support the creation of a prioritized list of stakeholders to engage with across the enterprise.

With a defined engagement strategy and list of contacts, the communications content needs to stimulate employees across different levels in the organization to create bottom-up as well as sanctioned top-down demand through events such as team

meetings, demonstration workshops, and town-hall events. The automation culture framework should be applied to develop and manage communications content on why and how automation is being applied, linking its purposefulness to the wider corporate business strategy or transformation initiative.

Corporate events need to resonate with the employee base on the opportunities automation can provide, and how it can improve and upskill while reducing any perceived job security threats through use cases humanized by existing staff. A choreographed engagement strategy supported by a communications plan should be executed with close alignment to the capability’s performance metrics. The number of engagements can then be ramped up or down based on key performance data, such as the current number of projects in a detailed design phase.

Evolving the automation lifecycle operating model

Scaling the automation capability to enterprise class requires a number of selective modifications to be made to the automation project lifecycle model. These changes must aim to address some of the key issues that are likely to emerge with a higher volume of projects being pushed into the automation factory. Changes to the project lifecycle model may include the addition of formal gateway reviews in between key stages, such as at the end of a PDD stage, to review, risk assess, and formally approve automation projects and Process Design Documentation before they incur build resource commitment.

Additional stages might be included such as “keystroke reviews” prior to moving projects into build stages, to address issues such as missing detail from PDD documents that would be required by developers. All these measures should aim to improve the efficiency of the end-to-end delivery funnel while maintaining quality, allowing the delivery processes to deal with a larger volume of projects and support a greater number of people using the processes.

The capability needs to carefully manage the introduction of the changes which are required, while being cognizant of the obvious

increases in bureaucracy this may cause. In order to maintain the fine trade-offs between agility and risk, the selective addition of incremental changes should support greater adoption and aim to seek direct feedback on the applied effectiveness of the changes.

Scaling the control room support capability

During the automation Accelerated Incubator stage, it is likely that once deployed, the digital workers will be supported by either the developers, some controllers, or typically a combination of both. The support would have been based on best endeavors, with developers being required to fix defects immediately, while in parallel developing new automation projects. Internal customers would use the path of least resistance by contacting developers directly, given the business impact of the digital worker stopping and failing to work the process; this is clearly not a sustainable model.

Organizations typically cite challenges in supporting automations as one of the main inhibitors to successfully scaling the automation capability. Ineffectively scaling the support team in line with the overall growth of the automation capability can significantly damage the credibility and long-term viability of the offering.

The automation CoE support function, or control room, differs in part from traditional support functions due to the distributed impact failed automated processes can have on the business, the inherent dependency on existing IT systems, and the very nature of change in an organization. The control room function should be perceived almost as a team of sports coaches whose purpose it is to constantly review and improve performance and ensure the "wellness" of its digital workers, which in turn should minimize incidents.

There may be a number of root causes from within the automation capability for the level of support incidents, such as the quality of the automation design or build, inadequate support processes, or poor customer communication management. Other reasons which are typically outside the control of the capability may include changes to robot access rights, underlying IT systems stability, or changes made to business processes without following internal

change management. Any of these issues can stop a digital worker. For the internal customer, whatever the root cause may be, it typically unfortunately manifests as being very much an automation issue.

Implementing established service management processes such as the ITIL (Information Technology Infrastructure Library) framework will help ensure the service design follows industry best practices across key areas such as incident management, service level agreements, and contact management. Where possible, organizations should adopt the existing enterprise-wide IT service management process and first line, with automation being one of the types of incident categories that can be raised.

Current industry best practice suggests the ideal ratio of digital workers to controllers is approximately 20:1, although this will be heavily influenced by the complexity of the processes automated. With automation technology maturing alongside newer features that provide better support, it is expected that greater economies of scale will emerge. Identifying the average costs of support will allow the projected operational costs of the service to be estimated as the capability expands.

Business processes, like the organizations they serve, are subject to change, and while one of the key advantages to automation is the flexibility in rapidly building digital workers, the management of a high frequency of changes requested from the business can create unplanned demand and prove challenging to meet in line with the requirements of the business and IT.

A defined change management process will support in managing customers’ expectations and prioritizing based on business risk. An effective change management approach encourages the business customer to submit requests for changes to automations early, so that the effort to build and test changes to automations can be planned well in advance in troughs of delivery cycle activity. Adopting the same approach for continuous improvement of the digital workers will demonstrate the value add of the controller model and help generate collaborative relationships between the automation capability and its internal customers.

Additional changes to the team structure, such as regularly rotating developers to the controller function for short periods, should allow the bulk of the changes to be implemented while providing developers with an appreciation of being on the support “front line.”

Enterprise Scaler stage checklist

- Secure board-level sponsorship

- Define an automation strategy that enables the wider corporate strategy or digital transformation program

- Agree the new program’s funding model and supporting business plan

- Establish enterprise-grade benefits management and governance processes

- Redesign the automation capability to support flexible volume growth with partners

- Upskill and iterate the structure of the automation team to deliver scale and increasing complexity

- Initiate organization-wide automation education initiatives

- Develop an enterprise-wide engagement strategy and supporting communications plan

- Iterate the automation project lifecycle model

- Mature and harden the control room support processes

- Actively engage board-level sponsorship to share performance, promote the capability, and unblock key issues.

Intelligent Automation Innovator stage

The key objectives of the Intelligent Automation Innovator stage are:

- Align the intelligent automation strategy to enable the organization’s digital transformation program

- Demonstrate strategic value contribution through the delivery of integrated intelligent automation solutions

- Systematically increase the intelligent automation technology portfolio

- Create an innovation-centered integrated intelligent automation team

- Extend enterprise engagement to support strategic intelligent automation-driven change.

Following a level of automation maturity developed as a result of the Accelerated Incubator stage or before, after or during enterprise scaling, there will be a recognition of the limits within which automation in isolation can resolve the organization’s challenges and support its digital transformation. Intelligent automation extends the capabilities of technology by providing the opportunity to go well beyond the “low-hanging fruit” of automating “as-is” business processes, with a view to using cognitive automation technologies to significantly improve and redesign work.

Transitioning to an intelligent automation strategy

Although the organization should now have an existing set of competencies in automation, extending this with intelligent automation to unlock higher value-based growth will require a clear supporting strategy. The Intelligent Automation Maturity Framework allows the organization to map its existing capability alongside its preferred trajectory, which in turn can be articulated in the intelligent automation strategy.

Figure 6.2

shows the automation maturity profile of an organization. While the business has been able to scale its capability to support some level of enterprise scaling, it has achieved this predominantly through simpler process automations. The pursuit of greater automation volume and efficient delivery timescales (shown by the velocity) has been at the expense of less complex automations.

In this example, a lower-risk strategy may be the incremental development of the organization’s process breadth and cognitive scope capability. This will allow the business to develop the necessary competencies involved in delivering more complex business process improvements while introducing some level of new technologies in pilot form to trial. In turn, this may stagnate or even reduce the total volume of automation projects delivered.

As shown by the example, intelligent automation is not simply the addition of “more tech.” It is a holistic change in the organization’s competency to deliver changes to work, people, and technologies. As such, the intelligent automation strategy should define the key changes required across a number of key elements to achieve these new goals, from the organizational design and team structures to partnership ecosystems and the selection of technologies and supporting delivery processes.

The strategy should provide a roadmap that clearly links the current state of the capability to a new end state, which is strategically aligned to enable the wider transformational objectives of the business.

There is a risk of leadership significantly underestimating the complexities and risks involved in transitioning towards the application of intelligently automated solutions. Expectations based on the delivery of previously simple automations, such as time to build and deploy, and cost, will need to be realigned through an appreciation of the increased complexity—higher risks but significantly higher rewards.

One of the challenges in transitioning to delivering greater value is the tangibility of benefits. With low-complexity automations, the benefits are typically easily quantifiable and directly attributed to, for example, the reduction in third-party outsourcing costs. With the introduction of more complex intelligent automation solutions, the benefits management approach will need to be realigned to recognize that it is solving more complex challenges.

Intelligent automation enabled digitalization efforts may be embedded within a number of existing transformational initiatives. These could be funded through several corporate pots aimed at delivering percentage uplifts, for example in revenues generated from new market offerings. The automation strategy should support in defining the necessary changes to the benefits management approach, such as attribution of benefits and revamped sign-off processes. It will be critical that there is still an alignment between value delivered and the costs of the intelligent automation capability.

Finally, because the business value of using complementary technologies such as AI and analytics requires the canvas of enterprise scale to really add value, this in turn will require the intelligent automation capability to have a clear mandate to interact across the span of the enterprise. Following successful proof of the existing automation capability, senior leadership should provide the backing, either indirectly through the association of intelligent automation with the existing transformational initiative, or directly. This allows the newly emerging intelligent automation capability to interact with business expertise across the breadth of processes and vertical business lines with the aim of identifying automation opportunities that are of a significantly greater value.

Creating the automation innovation team

The adoption of complementary technologies from across the intelligent automation stack will have varying dependencies on new skills and delivery methodologies, which will therefore require evolutions to the existing automation organizational design and working practices.

For example, business analysts, as well as being able to improve existing processes, will require new skill sets to design optimal divisions of labor between humans and the intelligent automation technologies. The application of AI and automation to a specific business challenge may require interfacing with teams in IT for the provision of new and existing data sets. The creation of supervised learning algorithms may require a number of constant iterations and reviews with subject matter experts in the business.

While there may be a number of specific technology-driven best practices and specialist skill sets, the intelligent automation capability will critically have to unite these into a single delivery philosophy. Approaches such as agile can create an experiment-driven design culture, one that is more fluid and discovery-oriented towards work process design. It uses principles such as design thinking workshops to create an “outwards-in” approach, with the customer shaping the business. This should support development which can be rapidly prototyped, deployed, and iterated through increments of refinement and value validation.

Delivery approaches discussed earlier such as squads—multi-skilled, highly independent, performance-driven units of capacity—can be adopted as an approach. Although using new approaches such as agile may be a significant departure from the organization’s existing delivery methodologies, the developing intelligent automation capability must be seen as a microcosm of what the wider enterprise needs to become: an agile, performance-driven, and value-focused business.

Rather than changing the structure of the current automation capability, such as a centralized CoE, an emerging intelligent automation capability may need to adapt to the organization’s existing competency centers to create unique organizational designs. Most corporates will have existing analytics and possibly AI teams, requiring more complicated integrative structures and potentially the alignment of resources towards temporary projects and programs. The success and challenges of previous such initiatives can provide valuable lessons and inform changes that minimize risks. The active development of the automation team’s technical expertise and soft skills will be critical to the successful adoption of an intelligent automation capability.

Engagement towards strategic initiatives

The emerging intelligent automation capability needs to be able to successfully communicate the expanded repertoire of technological solutions and the potential opportunities these new toolsets provide in solving key challenges. The type of organization and level of digital mobility should help to inform how complementary technologies should be communicated, given the risks of easily confusing stakeholders.

Management can sometimes associate dazzling presentations of tech with failed projects. So intelligent automation engagement activity should introduce only a few technologies at a time, focusing more on their synergistic applications through relatable use cases that can be easily understood and applied to current business challenges.

Communication content should use the automation culture

framework to reinstate the alignment between the purpose of the business transformation and the new enterprise-wide mandate of intelligent automation to generate new opportunities.

Intelligent automation is more likely to initially be adopted by stakeholders with existing digital workers—the early adopters and benefactors of automation. The potential identification of new value opportunities should aim to expand the understanding of existing point automations by mobilizing the required resources to support an end-to-end process review.

The output of these reviews may generate a roadmap of incremental changes that can be applied to employees, their work, and the technology to create new intelligent digital processes. Effectively communicating the range of these new automation technologies can be achieved by looking to upskill existing digital workers with greater cognitive capabilities.

Reviewing the list of previous automation project opportunities may also prove to be a useful way of identifying new applications of intelligent automation. Historical opportunities rejected as unsuitable for automation because they required more complex cognitive functions to be performed by users, such as reading documents to understand their content or specific problem-solving tasks, may now be automated using the range of tools that intelligent automation provides.

Good business analysis disciplines established at the outset of the automation capability, mandating team members to document reasons why a specific project has been rejected, will serve to pay dividends downstream.

With an appetite for moving up the automation benefits trajectory and enabling greater value, the capability can move away from the earlier “mass-marketing” methods towards engagement activity that is considerably more strategically aligned to the identification of digitalization and transformational automation opportunities. These engagements will be initiated by a combination of top-down introductions and the existing knowledge of key business challenges.

An established automation capability based on a reputation of delivery and customer excellence, coupled with an ability to do

more through intelligent automation and senior sponsorship, should support in generating a healthy pipeline of new automation projects that can be prioritized based on their ability to deliver combinations of short- and long-term value.

Transitioning to greater automation complexity

One of the most essential transitions for the emerging intelligent automation capability will be its ability to shift towards solving more complex business challenges. This evolution will be important to establishing the long-term value of the capability. The impact of global disruption is creating a tidal wave of change in how work is conducted and managed, demanding that these new intelligent automation technologies deliver.

These intelligent automation solutions will require an intimate understanding of the complete business process, its purpose, and its value. More specialized business process analysis skills will be needed, along with more intrusive techniques such as value stream analysis and design thinking to optimize, improve, and redesign. In a complex organizational environment where processes traverse business division lines, it calls for business improvement resources who are not only technically competent but able to demonstrate strong communication, analysis, organizational, and relationship skills to drive cross-functional collaboration.

Common work activities that typically involve larger numbers of employees may also benefit from additional technologies such as process mining tools to increase the speed and accuracy of capturing existing process states and modeling the impact of process and automation changes.

Collaborative explorations led by business analysis specialists will typically identify different components of change across people and technology as well as the processes themselves. Fundamentally, the prescribed changes are based on knowledge of the business and the intelligent automation technology toolset and will be applied as varying combinations of digitization, digitalization, and transformational process changes. These need to be articulated as

detailed roadmaps that take the organization from its current to its future state, directly enabling the wider transformational agenda and new strategic business initiatives.

Expanding the intelligent automation technology

With intelligent automation, the simplicity of RPA technology is enhanced with a new array of tools that vary considerably in their levels of sophistication and technical dependencies, from “plug and play” OCR tools to complex deep-learning algorithms. The emergence of the automation platform provides organizations with a cloud-based “one-stop shop” and the ability to augment automation with advanced complementary cognitive technologies. While this has reduced the risks associated with IT systems integration, the bane of many large IT programs, the automation platforms risk locking organizations into an ecosystem of proprietary technologies and third-party products.

As discussed earlier, the selection of a preferred automation vendor needs to critically asses the level of complementary technologies available, their alignment to internal IT standards and frameworks, and importantly their ability to support the digital transformation agenda.

It would be expected that, in parallel to scaling up the core automation activity or towards the end of the incubation stage, the organization pilot a select number of tools from the intelligent automation technology portfolio. This selection should be informed by existing knowledge and understanding of which technologies may be particularly applicable across a wider range of use cases in the organization. For example, a knowledge-intensive legal practice may benefit significantly from the implementation of an intelligent document analysis solution alongside RPA, whereas a financial services organization may benefit from AI and automation.

The complexities and associated risks of introducing additional technologies require the organization to establish a structured pilot innovation process, with the aim of rapidly evaluating the feasibility of complementary tools within the intelligent automation stack. The

process should be defined and facilitated by a cross-functional team of resources in key areas such as IT, the supporting business, and the automation capability, which are empowered to assess the value these additional technologies can bring to the enterprise.

IT would be required to confirm their adherence to existing corporate technology standards and key areas such as data security, integration with legacy systems, and alignment to a data strategy. Procurement would support in providing cost comparisons and reducing any key contractual blockers that may inhibit early piloting and adoption. Finally, carefully selected business process expertise would provide viability of the features of the technologies and their ability to tackle the range of business challenges and the change footprint required by the organization for successful adoption.

Following the rapid mobilization of pilot deployments, the wider impact of introducing these changes to existing automation capability delivery processes can be extended. This could mean modifications to the automation project lifecycle model or the addition of specific business training requirements, especially given the new roles of augmented human and automation collaboration. Adopting the principles of automation plasticity should help to evolve the automation capability through the addition of intelligent automation clusters—combinations of proven technology that can be interlinked to form increasingly complex but unique and fluid cognitive solutions.

Intelligent Automation Innovator stage checklist

- Align the emerging intelligent automation capability to enable the wider business transformation initiative

- Develop an engagement and communications plan focused on intelligent automation solution capabilities

- Establish a systematic process to rapidly review and pilot potential intelligent automation technologies

- Increase the required skills, processes, and technologies in the automation capability to support complex business process

analysis, improvement, redesign, and change management

- Update the automation organizational design model to integrate key technological competencies

- Agree revisions to program funding, business plan, and benefits management approach

- Upgrade the PMO and a data-driven performance management capability

- Optimize the automation technology platform to enable complementary technologies

- Select and agree new working practices with partners

- Develop the automation project lifecycle model

- Continue to build a delivery backlog of intelligent automation projects.