Chapter 5

Interpreting Chord Symbols and Musical Charts

Now let’s give your fingers a bit of a break and exercise the ol’ noggin a bit. As a bass player, we don’t play chords very often—that’s normally the job of the guitar player or keyboardist. However, it’s very important that we know what chord symbols mean, because there will be times when you’ll need to create a bass line on the spot with nothing more than a chord chart.

A chord chart—sometimes called a lead sheet or fake sheet—contains a melody, lyrics (if applicable), and chord symbols. In the professional arena, musicians are expected to be able to use a lead sheet to perform a song that they’ve never heard before (or at least don’t know by heart). While this may sound daunting at first, once you have a few basic concepts under your belt, it’s not nearly as bad as it sounds. As a bassist, the most important thing is the ability to understand chord symbols.

The simplest method for constructing bass lines is to just play the root of each chord in whichever rhythm seems to suit the song (listening to the kick drum can help out here!). As such, the bass lines in the two songs at the end of this chapter will solely consist of root notes. Other elements on a lead sheet include routing directions, repeat signs, and tempo markings. We’ll look at each of these over the course of this chapter, but let’s start with the all-important chord symbols.

Chord Symbol Nomenclature

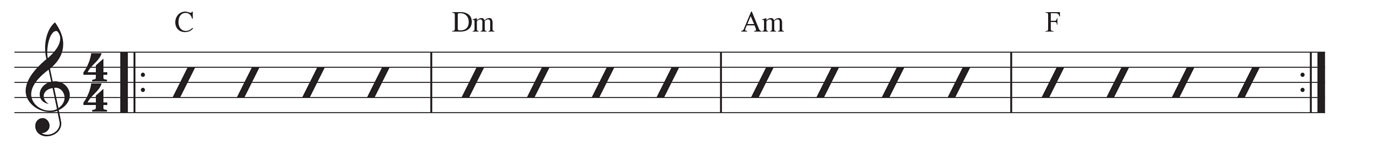

If you see only a capital letter, then a major chord is implied. For example, if you see “C,” then C major is implied; “D” means D major, etc. If you see a small “m” after the capital letter, such as “Cm,” then a minor chord is implied. You may also see a minus sign (“C-”) or perhaps “min” (“Cmin”). All of these symbols mean the same thing: minor. In the following example, we see chord symbols for C major, D minor, A minor, and F major. We also see repeat signs, which tell us to play through these four measures and then repeat them before moving on.

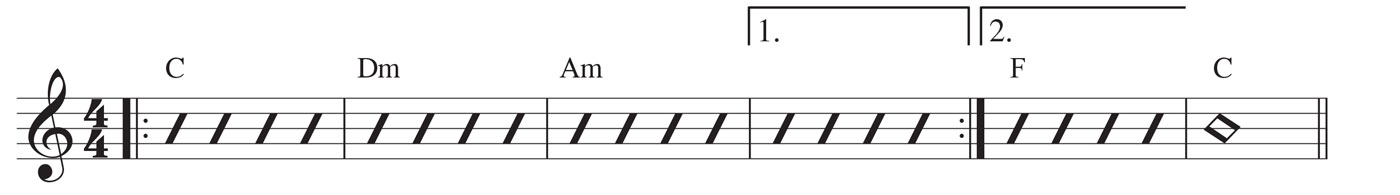

Note: Since they often contain a vocal melody or lead instrument melody, lead sheets often appear on treble clef. This isn’t a problem, though, because we’re usually only concerned with the chord symbols and the form of the song. Sometimes you’ll see first and second endings, as well. In the following example, you would do this:

- Play to the repeat sign (through measure 4);

- Go back to measure 1 and begin the repeat;

- Play through measure 3, skip from the first ending (measure 4) to the second ending (measure 5), and then continue on.

When Things Seem a Bit One-sided

Sometimes you’ll come to an ending, or closing, repeat sign without having seen an opening one . In this instance, you simply repeat from the very beginning of the song. It’s for reasons such as this that it’s always a good idea to quickly scan through a chart before trying to play it. This will allow you to catch these types of things and be prepared for them.

Chord Progressions

A chord progression is simply a series of chords strung together. The two examples on the previous page were chord progressions, as were the chords to the songs at the end of Chapter 4. There are certain chord progressions that are very popular and that are used all the time in pop, rock, blues, etc. One of the most popular is the I–IV–V progression. The Roman numerals here refer to chords built upon certain notes of a major scale. Let’s look at this more closely.

Major Keys

As we briefly discussed on page 26, a song is either in a major key or a minor key. Major keys contain the same arrangement of chords, regardless of the tonic (the root note of the key). A major scale has seven different notes, and each one of those notes can have a chord built upon it. When using Roman numerals, we apply uppercase ones to major chords and lowercase ones to minor chords.

The arrangement of chords for any major key is as follows:

I ii iii IV V vi vii˚

Note: The “ ˚ ” symbol after the vii chord stands for diminished, which is like a minor chord, but one note is different. You don’t need to know much about the diminished chord right now, as major and minor chords are much more common. The key of C, which contains no sharps or flats, is spelled: C–D–E–F–G–A–B. (C is the only major key with no sharps or flats; all other major keys require one or more sharps or flats.) Therefore, if we apply the above chord arrangement formula to this key, we’ll get the following diatonic chords:

C Dm Em F G Am B˚

I ii iii IV V vi vii˚

Note: There are certainly times when you’ll come across a chord other than these seven while in the key of C (Bb would be a common one). These are referred to as non-diatonic chords, which is a can of worms too big to open in this book. So, a I–IV–V progression in the key of C would contain C (I), F (IV), and G (V) chords. Make sense? Other common major-key progressions include the following:

I–V–vi–IV: (in C) C–G–Am–F

I–ii–iii–IV: (in C) C–Dm–Em–F

I–IV–I–IV: (in C) C–F–C–F

So what about other keys? Good question! Each major key has its own key signature—or collection of sharps or flats that it uses throughout the piece of music. The key signature for C major is blank, but every other major key will display one or more sharps or flats in the music. This is something that you’ll eventually want to memorize, but for now, I’ll just list them here for reference. Using this information, you’ll be able to find the chords to any progression in any major key.

The 12 Major Scales

C Major: C–D–E–F–G–A–B |

F Major: F–G–A–B–C–D–E |

G Major: G–A–B–C–D–E–F |

Bb Major: B–C–D–E–F–G–A |

D Major: D–E–F–G–A–B–C |

Eb Major: E–F–G–A–B–C–D |

A Major: A–B–C–D–E–F–G |

Ab Major: A–B–C–D–E–F–G |

E Major: E–F–G–A–B–C–D |

Db Major: D–E–F–G–A–B–C |

B Major: B–C–D–E–F–G–A |

Gb Major: G–A–B–C–D–E–F |

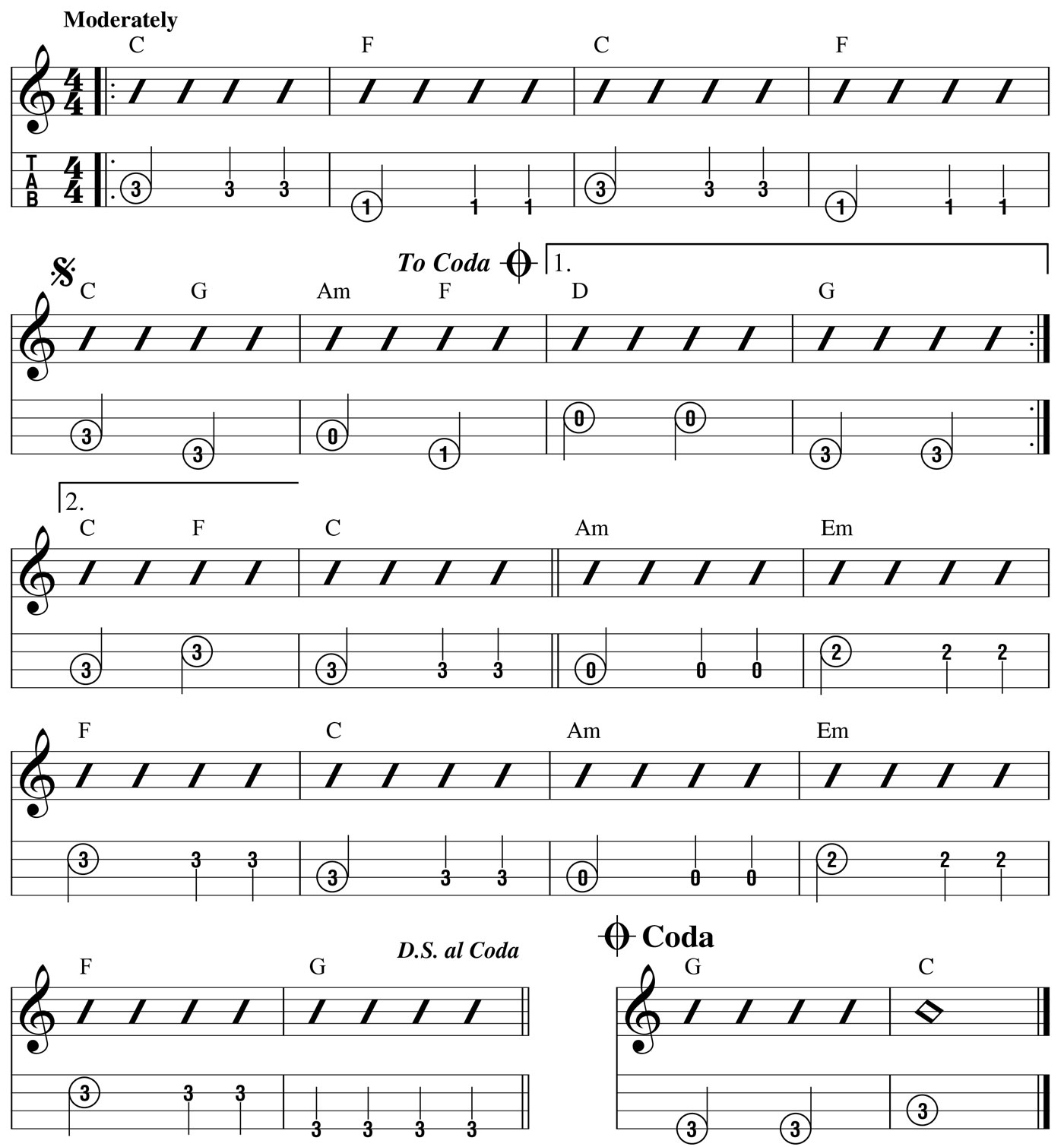

Song 4: Chord Chart Rock in C

Here’s a chart for a rock song in in the key of C major, along with a bass line that you might play if you were reading the chart. Notice that only the root note of each chord (the note from which the chord gets its name) is played. In addition to the repeat sign, we see another routing element: D.S. al Coda (“del segno al coda”). This is Italian and essentially means “from the sign to the Coda.” When you reach this instruction, you go back to the “sign” ( d ) and play until you see the “To Coda” instruction. At that point, you skip to the Coda section, which is indicated with the big crosshair symbol ( c ). This is simply a notational device that eliminates having to write out an entire section twice. Also notice the tempo indicator at the beginning of the song, which tells us that this song will move along at a moderate tempo. Sometimes you’ll see a precise beats-per-minute (bpm) marking, such as D = 120.

Example 22

Chord Chart Rock in C

Song 5: Chord Chart Ballad in G

Here’s a chart for a ballad in the key of G. You should be able to get through this one without many problems, but there’s one new routing direction: D.C. al Coda (“da capo al coda”). This is Italian for “from the head to the coda.” In this case, the “head” refers to the top—the beginning of the song. So, when you reach that instruction, go back to the beginning and play until you see “To Coda,” at which point you jump to the Coda section.

Example 23

Chord Chart Ballad in G