THE FATHER OF THE FOREST SERVICE

ON AUGUST 22, 1896, WHILE RIDING ON THE NORTHERN PACIFIC line from Tacoma to Kalama, Gifford Pinchot gazed out the window of his Pullman coach at the vast forest that would someday bear his name. It was a magnificent sight. The Douglas fir trees swooped down from the high country like an immense green cloak draped over the land’s bare shoulders. Even from a distance, Pinchot could make out the individual trunks, ten or more feet across, standing separately above the undergrowth, like solitary men, proud and independent. The forest reminded him of other great forests he’d seen: the redwoods near Yosemite, the vast pineries of northern Europe, the hardwood forests near the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. Yet this forest seemed to extend much farther than any of those forests, rising in successive waves to the east, to the distant volcano that Meriwether Lewis, when he was traveling up the Columbia River almost a century earlier, called “the most noble looking object of its kind in nature.”

Though he had just turned thirty-one in the summer of 1896, Gifford Pinchot always seemed older than his age. Partly it was his great height and cadaverous bearing, which reminded some onlookers of the trees he so admired. Partly it was the bushy mustache overhanging his upper lip, which he had grown as a student at Yale and had cultivated ever since. And he was a serious man, committed to his calling and to his god, so that his passions were rarely checked by self-doubt. He had wanted to be a forester since he was a senior in high school. Now he was one, and through careful maneuvering he had put himself in a position to make decisions about some of the greatest forests the world had ever seen.

Pinchot always acted with the assurance of someone who expected to do great things. His grandfather, Cyrille Pinchot, had emigrated to America from France in 1816 when his family cast its lot with Napoleon right before Waterloo. Settling first in New York City and then on four hundred acres of rich farmland outside Milford, Pennsylvania, near the Delaware River, the family established a store that exchanged raw materials from western New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York for finished goods moving in the opposite direction. As a young man, Cyrille began buying land in the area and hiring tenant farmers to raise crops. He also bought forested land, clearcut the trees, and bound the wood in rafts to float down the Delaware to sell to lumbermen in Trenton, Philadelphia, and other cities. He reinvested his money in more farms, more timberland, and, eventually, property in the expanding towns of the region.

By the time Cyrille’s second son, James, came of age in the 1850s, the family fortune was sufficient for a pivot away from farming, timber, and country stores. James moved to New York and started a lucrative business in interior furnishings—wallpaper, window shades, and curtains—while also moving into the high echelons of New York society. In 1864 he married Mary Jane Eno, the daughter of a wealthy New York merchant and land speculator. They were friends and patrons of several prominent landscape artists, including Sanford Gifford, after whom James and Mary would name their first son in 1865. James became involved with the National Academy of Design and helped establish the American Museum of Natural History. He was in the vanguard of the city’s social, economic, and cultural elite.

Gifford Pinchot grew up in New York City, spent his summers in Simsbury, Connecticut, and attended Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire before entering Yale in 1885. He was groomed for a life of service, not commerce. When he was growing up, his parents gave him a copy of a book that was hugely influential in the second half of the nineteenth century, Man and Nature by George Perkins Marsh. In that book, published in 1864, Marsh—a scholar of ancient languages, a former congressman from Vermont, and a longtime diplomat in Italy—argued that the classical civilizations bordering the Mediterranean had collapsed because of environmental degradation. In particular, by cutting their forests, these civilizations had impoverished the soil and hastened the spread of deserts, which weakened the foundations of government and society. Now Americans were embarked upon the same heedless course. By destroying the forests of the eastern United States and Midwest, the country was destined to collapse just like Greece and Rome, Marsh wrote. Only if the nation restored its land, conserved its forests, and protected its soils and waterways would it avoid catastrophic decline.

Gifford Pinchot’s father had always regretted the desolate condition in which his family had left the woodlands of eastern Pennsylvania during its rise to prominence and wealth. For him, the ideal landscapes were the pastorals depicted in Sanford Gifford’s paintings; the second-growth forests of the Adirondacks, where the family went on camping and fishing trips; or the cultivated fields and copses seen through railway windows on European sojourns. In his son, James Pinchot saw a chance to rectify his father’s and grandfather’s mistakes. Right before Gifford entered Yale, his father asked him, “How would you like to be a forester?” It was “an amazing question for that day and generation,” Pinchot wrote later in his autobiography. In 1885, no American university offered courses in the establishment, management, and preservation of forests, and no American had ever become a forester, though some European-trained foresters were working in the United States. The idea that an American would make forestry a career, in an age when the forests were being rapidly exterminated from large swaths of the country, seemed a non sequitur.

Pinchot was immediately enamored of the idea. Throughout his time at Yale, he proclaimed his intentions to his classmates and pestered his science professors for information about his chosen profession, even though there was little they could tell him. He also threw himself into Yale life with abandon. He was a reserve on the great Walter Camp football teams of the 1880s, taught in the Yale Sunday school, and was tapped for Skull and Bones at the end of his junior year. During his senior year, he flirted with the idea of going to work for the YMCA at Yale after graduation—both of his parents had also instilled in him a powerful religious sense—but in the end he opted for forestry, making as a graduation speaker his “first public statement on the importance of Forestry to the United States.”

For several months he traveled through Europe gathering forestry texts, meeting with prominent foresters, and touring the meticulously managed forests of England, France, and Germany. At the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, Pinchot was more impressed by the Eaux et Forêts exhibit than by the newly built Eiffel Tower. The exhibit provided an exhaustive survey of forestry and hydrology, extolling the rational management of the landscape and the triumph of French forestry over nature. “The exhibit is magnificent and so complete that at first I despaired of making any adequate description of it,” Pinchot wrote in his dairy. That fall he enrolled at L’École Nationale Forestrière in Nancy, intending to make a thorough study of the subject. But he preferred hiking in the nearby woods to his classes, where he observed how the forests were being cut, reforested, and then cut again, all through the application of sound scientific principles by civic-minded foresters. In this way, he wrote, “a permanent population of trained men” could enable “permanent forest industries, supported and guaranteed by a fixed and annual supply of trees ready for the ax.”

Though the European foresters he met encouraged him to remain in Europe and earn a PhD, Pinchot was impatient to get started on his career. In December, he set sail for America, “willing to try with what knowledge I have now.” He wrote for outdoors periodicals and spoke at national conferences on issues related to forestry, met with the European-educated foresters then working in America, and did some work for Phelps Dodge & Company, a large mining and timber concern with which he had family connections. In 1892 he took a job as the forester of George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, where he first applied his ideas about how to manage American forests. He was becoming known in the small community of university and government scientists interested in forest preservation, and no one was surprised when, in the spring of 1896, he was named secretary of the National Academy of Sciences’ Committee on the Inauguration of a Rational Forest Policy for the Forested Lands of the United States—more popularly known as the National Forest Commission.

The impetus to establish such a commission had been growing for years. The three decades after the Civil War were a period of steadily increasing environmental concern in the United States, triggered largely by the industrial cutting of America’s forests. Marsh’s book was one of several that predicted disaster if the despoliation of the land continued. Writers raised concerns about a “timber famine,” such as the widespread shortages that had been occurring in parts of western Europe for centuries. As the secretary of the Interior warned in 1877, “If we go on at the present rate, the supply of timber in the United States will, in less than twenty years, fall considerably short of our home necessities.” Despite such warnings, the destruction of forests in New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and large parts of the South during the United States’ first century was immediately followed by the widespread devastation of forests in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota at the beginning of its second. Once the trees were gone, the leftover slash was often burned, leaving a wasteland of charred stumps. What to do with this cutover land was a major problem. Often the timber companies simply quit paying local taxes on the property they owned so that the worthless land reverted back to the state. In other cases, the timber companies tried to sell the cutover land to farmers, but the sandy soils and harsh winters of the upper Midwest reduced many such farmers to penury and then bankruptcy. The eminent forest historian Michael Williams describes the scene:

There was a high rate of failure, and the survivors hung on to lead a wretched life, trying to eke out an existence. The cutover areas were (and still are in places) dotted with derelict fences and sagging, unpainted farmhouses, some mere tar-paper shacks. In the deserted fields occasionally one still sees a lilac tree or a heap of stones where a chimney once stood, both markers of an abandoned homestead, the whole scene a mute and melancholy testimony to abandoned hopes in the former forested lands.

Even as the forests of the Midwest were being eliminated, a new generation of advocates like Walt Whitman and John Muir, building on the transcendentalism of Thoreau and Emerson, were defending forests for their own sake, as mystical places where individuals could re-create themselves, realizing the inherent worth and dignity of both people and nature. American landscape painters depicted a world in which humans and nature coexisted, each acquiring attributes of the other in a romantic union of man and his environment. In a time of religious revival, the destruction of the forests seemed to represent the expulsion of Americans from their Edenic paradise. Only the preservation of wilderness could safeguard America’s innocence.

In 1891, concerns about American forests coalesced in a remarkable piece of legislation, which Pinchot later called “the most important legislation in the history of Forestry in America.” Without quite knowing what it had done, Congress passed a law that included an obscure provision stipulating that “the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve [land] in any State or territory having public land bearing forests . . . as public reservations.” Almost immediately, President Benjamin Harrison created 13 million acres of reserves from Arizona to Washington. His successor, Grover Cleveland, added another 4.5 million acres a year later.

The 1891 legislation marked a dramatic turn in America’s policies toward its vast landholdings. Except for areas of exceptional natural beauty—Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872 as “a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” followed by the creation of Yosemite National Park in 1890—government policy had always been oriented toward “disposal”—getting land into the hands of private owners as quickly as possible. Yeoman farmers were the preferred owners, stemming from the Jeffersonian belief that small landowners were the best bulwarks against tyranny. Beginning during the Civil War, homestead acts granted quarter-square-mile plots to claimants willing to settle the land and farm.

By the 1890s it was clear that these policies had gone seriously awry in the western United States. Farmers were largely uninterested in the vast majority of the land west of the 100th meridian, where rainfall was too sparse to support crops. Even the great forests of the West generally grew on land too steep, too isolated, or too rocky for agriculture. Instead, timber companies sought to acquire this land, whether legally or illegally. Many companies paid loggers, sailors, and other surrogates to claim forested lands as if they were going to clear the trees and raise crops, after which the claimants signed over the deeds to the companies. In many cases, western settlers simply assumed that the land was theirs to use, regardless of ownership. Timber was brazenly stolen from federally owned lands by settlers, mining prospectors, railroad contractors, and others, with no payment to the government. Ranchers fenced in vast tracts of public land to graze their livestock. The western lands were being lost or given away without compensation. As a land commissioner wrote in 1891, “A national calamity is being rapidly and surely brought upon the country by the useless destruction of the forests. Much of this destruction arises from the abuses of the beneficent laws for giving lands to the landless.”

The creation of the first forest reserves in 1891 heralded a new era. Henceforth, the government would set aside large portions of the American West—and eventually portions of eastern forests—as federally owned land reserved for the use of the American people as a whole. No longer was the intention to give away or sell every last piece of land. Some of it would be reserved for the greater good. What Wallace Stegner said of the national parks applied to the forest reserves as well: They were “the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst. Without them, millions of American lives, including mine, would have been poorer.”

Though many westerners supported the creation of the forest reserves, their establishment also caused great consternation among politicians, landowners, and businessmen—especially those who had been getting rich from the exploitation of western lands. The bill sanctioning the reserves contained no provisions for their management or use. How was the federal government to manage these lands? Would the land still be open to logging, mining, and grazing? Would the reserves be expanded into other areas? Were they forever to be off limits, as their name would suggest?

To answer these questions, the secretary of the Interior requested that the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, form the National Forest Commission to investigate whether it was “desirable and practicable to preserve from fire and to maintain permanently as forested lands those portions of the public domain now bearing wood.” The chairman of the commission was Charles Sprague Sargent, the curator of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard and author of the monumental 1884 Report on the Forests of North America. The commission also included John Muir, who had founded the Sierra Club in 1892 and insisted on being an “observer” to the commission to maintain his independence from its conclusions; Henry Abbott, an army engineer; William Brewer, a prominent Harvard botanist; Arnold Hague of the US Geological Survey; and the zoologist and engineer Alexander Agassiz. And thirty-year-old Gifford Pinchot, the only member of the commission who was not a member of the academy, was named its secretary.

Of course, the commissioners could not very well recommend what to do with land they had never seen, so in the summer of 1896 they set off on a grand tour of the American West. Meeting in western Montana, they hiked through the Bitterroot Valley and nearby portions of Montana and Idaho. Traveling on the Northern Pacific line, the commissioners passed through Spokane, over Stampede Pass to Tacoma, and then south to Portland. By coach, railcar, and flatboat, they journeyed along the Willamette, Rogue, and Umpqua valleys of Oregon, visiting Klamath and Crater Lakes. Then they traveled south to California, where they viewed the Sierra, San Bernardino, and San Jacinto mountain ranges. They went to Arizona, touring the Grand Canyon, and passed through New Mexico on their way to Pikes Peak, where they rode to the top in a stagecoach. By October they were heading back to Washington, DC, to write their report.

Even during their trip through the West, divisions on the commission were becoming apparent—divisions that continue to split environmentalists to this day. Muir and Sargent, joined by Agassiz and Abbott, were preservationists. They wanted not only to stop the destruction of the forests but to halt their future development. President Cleveland should immediately create more forest reserves, they believed, and then use the army to guard the reserves from timber thieves and fire.

Pinchot, joined by Hague, had a very different opinion. Pinchot’s study of forestry in Europe had convinced him that the forests could be used without being destroyed. He favored the utilitarian conservation of resources, not their inviolate preservation. The application of science through an enlightened corps of well-trained foresters could provide all things to all people—timber, water, recreation, and wildlife preservation—an idea that eventually became known as the “multiple use” doctrine. Pinchot wanted the commission to urge Congress to develop a management plan for the forests before Cleveland created any additional forest reserves. That way, Congress would be less likely to object to the creation of future reserves and roll back the progress already made.

Pinchot lost this battle. In a preliminary report to the secretary of the Interior on February 1, 1897, the commission recommended the establishment of thirteen new forest reserves covering more than 21 million acres, to be added to the seventeen reserves already existing. The report called for the army to protect the reserves and made no mention of how they were to be managed or used. Three weeks later, on February 22, President Cleveland issued proclamations establishing the reserves recommended by the commission, just two weeks before he was to leave the White House. The act brought him great satisfaction. When three officials from the American Forestry Association, which was founded in 1875 during the United States’ first wave of environmental activism, came to thank him, they were ushered into the Oval Office past a row of politicians who had been waiting for an audience. “This is the first time anybody has thanked me for anything for a long time,” Cleveland said. “Let that bunch of favor-seekers rot in their chairs.” They talked for more than an hour, during which Cleveland exclaimed that he had created twice as many reservations as most men would have thought advisable. “A Republican president will succeed me, and he will undo half of what I have done, so to be safe I have done aplenty.”

• • •

By 1905, Pinchot had regrouped from the National Forest Commission’s rejection of his ideas. He was ready to try again to place America’s forests under sound management principles. And this time he succeeded.

Seven years earlier, on the basis of his work on the National Forest Commission and his many connections in government, Pinchot had been named Chief of the Division of Forestry in the US Department of Agriculture. The title was soon changed to “Forester,” which pleased Pinchot, since “in Washington chiefs of division were thick as leaves in Vallombrosa. Foresters were not.” It was a grand title for a job with little real power. The forest reserves were under the Department of the Interior, which also oversaw the national parks. The Division of Forestry in the Agriculture Department had no jurisdiction over the reserves or any other public lands. As Charles Sargent, the former president of the Forest Commission, wrote to John Muir, “This is a good place for [Pinchot]. He can do no harm there and after a very short time people will cease to pay any attention to what he says.”

Pinchot, as usual, proposed a big solution for what he saw as a big problem. He began to advocate for moving the forest reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture. There the forests could be treated not as an untouchable relic, like the national parks, but as an agricultural commodity. They could produce, as he put it in his autobiography, “the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest run.”

Moving that much authority from one department to another is not an easy thing to do in Washington, DC, where the size of a department’s budget and clout is measured by the programs under its control. Success would take every bit of Pinchot’s persuasive power.

His cause was aided immeasurably by an assassin’s bullet. On September 6, 1901, an anarchist who had lost his job in the panic of 1893 shot President William McKinley as he was shaking hands with members of the public at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. McKinley died of gangrene eight days later after surgeons were unable to locate the bullet that had entered his abdomen. This brought to the presidency a man with whom Pinchot already had an intimate friendship: Teddy Roosevelt. Just two years earlier, when Roosevelt was governor of New York, he and Pinchot had engaged in a round of wrestling in the executive mansion in Albany—won by Roosevelt—followed by a round of boxing, which Pinchot won. “I had the honor of knocking the future President of the United States off his very solid pins,” Pinchot would later boast. When Roosevelt became president, the two men chopped wood for exercise together, hiked through Washington’s Rock Creek Park, rode horses, and swam in the Potomac River. Pinchot ghostwrote Roosevelt’s speeches on conservation, drafted legislation, and served as one of his closest advisers. Roosevelt was an ardent outdoorsman who burned to protect the natural places he so loved. But he could not have made nearly as much progress without Pinchot.

Pinchot had already been preparing the Agriculture Department to absorb the forest reserves. He had been hiring young men to work as foresters with the states and with private landowners, and many lumbermen, who themselves were worried about running out of wood, gladly accepted Pinchot’s offers of help. Many of the new foresters had degrees from the Yale School of Forestry, launched in the fall of 1900 with a $150,000 endowment (soon doubled) from the Pinchot family. Amazingly, Pinchot had even convinced the secretary of the Interior to back the transfer of the forest reserves, and Roosevelt also supported the shift of power to his friend. But the only way to transfer the forest reserves would be through congressional action, which would be very difficult to obtain.

Pinchot planned a major event as the culmination of his campaign. The American Forest Congress, held January 2–6, 1905, brought together four hundred representatives of all the groups with a stake in forest preservation, including prominent members of the lumber industry, railroads, grazing, irrigation, and government. Railroad baron James J. Hill, still touting his western holdings, wrote a letter saying that “the subject is of importance far beyond the general understanding of the public. . . . Irrigation and forestry are the two subjects which are to have a greater effect on the future prosperity of the United States than any other public questions.” Though Frederick Weyerhaeuser was ill and unable to attend, his youngest son, F. E. Weyerhaeuser, told Congress that “at present lumbermen are ready to consider seriously any proposition which may be made by those who have the conservative use of the forests at heart.” Roosevelt opened the conference with a speech, ghostwritten by Pinchot, entitled “The Forest in the Life of a Nation,” in which he praised Pinchot for bringing about a “business view” of the forests and posed the question “how best to combine use with preservation.” As Pinchot himself said, conservation was simply “good business.”

An odd event occurred at the convention. At one point Roosevelt departed from the text Pinchot had written for him and began to denounce timbermen, many of whom were in the audience. He castigated the men who “skin the country and go somewhere else . . . whose idea of developing the country is to cut every stick of timber off of it and then leave a barren desert for the homemaker who comes in after him. That man is a curse and not a blessing to the country.” These offhand remarks set back relations between government and the timber industry for years.

Despite this dustup, Congress was convinced. On February 1, 1905, it transferred the forest reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture, where they have remained to this day. The forest reserves soon were renamed the national forests, in keeping with Pinchot’s idea that they were there to be used, not reserved, and the Bureau of Forestry in the Interior Department became the Forest Service in the Agriculture Department. When Roosevelt became president in 1901, fifty-four forest reserves covered about 85 million acres. By the time he left office, the total area included in the national forests was more than 150 million acres, an area larger than California and New York combined. Over the course of Roosevelt’s presidency, he and Pinchot did more to preserve America’s forests than anyone else in US history. By that measure at least, Roosevelt earned his spot on Mount Rushmore with Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln.

When President Cleveland created the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve in 1897, Mount St. Helens was left out of the reserve, partly because of the commercial value of the forests right around the mountain. But an immense 1902 forest fire just south of the volcano dimmed private companies’ enthusiasm for the area. Five years later, Roosevelt and Pinchot succeeded in adding the area around the volcano to the renamed Columbia National Forest. That pushed the boundary of the national forest right up against Weyerhaeuser’s vast forestlands to the west.

That boundary is where Ed Osmond and his colleagues drew the lines for the red and blue zones in April 1980.

• • •

Gifford Pinchot, who was born in the final year of the Civil War, died the year after World War II ended. After a vigorous campaign to rename one of the national forests for the father of the Forest Service, Columbia National Forest was chosen because it was “one of the top forests in the United States.” On June 15, 1949, President Harry Truman signed the proclamation designating the Columbia National Forest the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. At the dedication ceremony later that year, Lyle Watts, the chief forester of the US Forest Service, said that those who worked with Pinchot remembered him “as a man of tremendous energy and enthusiasm, as an inspiring leader, as a zealous crusader. They knew him as a courageous, unflinching fighter in the public interest and for the public good. His cause did not need to be popular if it was right. He seemed at times to be fighting almost single-handedly; but history has shown that the people were behind him.”

Today, Gifford Pinchot is an ambiguous figure among environmentalists. People respect him for his vision and accomplishments. But by the time of his death, the shortcomings of his “multiple use” philosophy already were apparent. Before World War II, the Forest Service was largely a caretaker organization. Most of the nation’s lumber came from private land, and the Great Depression and war limited the demand for wood. That all changed after the war. As had been predicted for decades, private landowners were running out of timber. Most of the big companies like Weyerhaeuser still had uncut land, but small-scale loggers needed stumpage. Now, the loggers said, was the time to put Gifford Pinchot’s multiple-use philosophy to work.

The Forest Service had little trouble transitioning to this new era of “getting the cut out.” Returning servicemen studied forestry under the GI Bill, and many of these schools were oriented around the needs of the timber industry. The rapidly expanding suburbs demanded huge quantities of wood for joists, flooring, sills, studs, headers, millwork, stairs, siding, rafters, and plywood sheathing. At the time, forestry schools taught that old-growth forests were unproductive, disease-ridden, “decadent” fire hazards that needed to be removed so that new timber could grow. Both at the local and national level, producing more wood to boost the economy and help win the Cold War could make the Forest Service a bigger agency. The Forest Service built roads through isolated wilderness so that private logging trucks could bring out wood, becoming in essence the single largest road contractor in the nation. It had employees who did nothing but serve the timber industry and who were promoted and rewarded on the basis of how much timber they could liquidate. Highly efficient chainsaws could cut down forests far faster than men with handheld saws and axes. Track-mounted steel towers could hoist trees to landings, replacing the old practice of erecting hoists on tall spur trees. The cut on national forests in Washington and Oregon increased from 1 billion board feet in 1946 to a high of almost 6 billion board feet in 1973.

The greatly expanded harvests from the national forests served the needs of lumbermen and the economy. But the large-scale harvesting of western forests quickly ran up against a fundamental problem. More and more people wanted to use the forests for purposes other than timber production. Servicemen back from the war took their rapidly growing families into the woods on inexpensive family vacations. Outdoor companies like REI, founded in Seattle in 1938, began to sell lightweight and waterproof clothes and camping equipment, making it easier to camp, hike, and hunt. Hiking clubs like the Mountaineers in Washington State and the Mazamas in Oregon had been active since the end of the nineteenth century, but now the cognoscenti were joined by many more people who had a more casual but enduring connection to the outdoors. People came to the national forests to hike, bike, horseback ride, backpack, hunt, snowmobile, motorcycle, ski, swim, picnic, kayak, fish, camp, and simply drive. Flush with timber money, the Forest Service built extravagant ranger stations staffed with knowledgeable personnel to help people plan their trips. In the minds of many people, the national forests became largely indistinguishable from the national parks, even though the two were managed by different departments to serve different ends.

“Multiple use” was always a misnomer. Many of the functions Pinchot ascribed to forests are inherently in conflict. A clearcut mountainside no longer attracts hikers. Logging reduces the forests to cropland and nothing more. In contrast, preservation of the land generally ruled out logging or mining. Multiple use could mean designating different parts of the forest for different purposes, and for a long time the Forest Service took this approach. But battles over how the forests should be used were inevitable.

One of the most contentious battlegrounds was the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. By the 1970s, ten to twenty square miles of the forest were being cut every year. By 1980, almost all of the old-growth forests more than two hundred years old were gone, with newer forests growing in their stead. The rest of the old growth was fragmented into small, vulnerable blocks, and soon it would be gone. Superb scenery that generations of Washingtonians had admired for decades was marred by clearcutting, which the timber industry insisted was the only logical way to cut Douglas fir trees. Some of the clearcuts next to highways were hidden by screens of trees, which the Forest Service called “beauty strips,” so that passing motorists could not witness the destruction, but others were in clear sight on the sides of mountains and along river valleys. Sawmills and plywood mills sprung up to saw the timber from the national forests, and communities took shape around those mills. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest, along with many other national forests, was becoming a shabby patchwork of clearcuts surrounded by second-growth forests, with little original forest left.

Conservationists were increasingly alarmed. Unless they took action, there would be no more forests to conserve. National groups like the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and the Audubon Society stepped up their efforts in the Northwest, and smaller groups took shape to address specific issues. The management of the national forests could no longer be left to the Forest Service, the leaders of these groups contended. A different approach was needed.

SITTING AT THE KITCHEN TABLE IN HER MODEST LONGVIEW, WASHINGton, home, Susan Saul looked around at the piles of paper surrounding her and tried not to panic. The campaign to save the area around Mount St. Helens was getting nowhere. For decades, groups in Washington and Oregon had been trying to preserve the area around the volcano, but they had made almost no progress. All around the mountain, Weyerhaeuser and other companies were logging right up to the tree line on soils so thin that trees would never grow back. The Forest Service was building roads through the backcountry so loggers could get at the last remaining old growth. Duval was poking holes up and down the Green River valley, and if the company found enough ore, it would convert the valley into a gigantic open-pit copper mine. Soon it would be too late. Much of the area around the mountain would be nothing more than a blasted landscape of cutover forests and mine tailings.

In her kitchen, Saul was surrounded by the tools of the pre-computerized community organizer: envelopes, paper, brochures, maps, an IBM Selectric II typewriter, address labels, a waxer, pica rulers, a light table, Wite-Out, correction tape. By the spring of 1980, she was handling most of the direct mailings and lobbying for the Mount St. Helens Protective Association, while her co-chair, Noel McRae, did most of the organization’s day-to-day work. She never thought, when she walked into her first meeting three years before, that she’d soon be helping to lead the organization. She just figured that she should be involved, given how much hiking she did around the mountain. But the other members of the association had involved her in their work from that very first meeting. They were applying the conservationist Brock Evans’s injunction “endless pressure, endlessly applied.” They were writing letters, making proposals, meeting with public officials and the press. But they had little to show for their efforts. They needed more people, more pressure.

Sometimes to Saul it seemed hopeless. Look at the town where she lived—Longview, carved out of the primordial forests by Robert Long in the 1920s to house the thousands of millworkers in his sawmills. Even now, in the spring of 1980, despite the housing downturn, the Weyerhaeuser and Longview Fibre plants on the banks of the Columbia River were pumping so much smoke into the air that, when the wind blew from the south, everything was covered with a thin sheen of ash. Any slowdown in the timber industry would put more people out of work, the people who lived on her street, the people she met in the supermarket. And they would blame her and the association.

But the blame lay elsewhere, Saul knew. Weyerhaeuser was about to run out of old-growth trees, after which the company was likely to get out of the old-growth business, since it rarely bought trees from the Forest Service. Saul’s father worked in a sawmill in Springfield, Oregon, where she’d grown up. She knew that the industry couldn’t survive the way it was going. It was extracting wood from the forests the way a mining company extracted gold from the ground. When the gold ran out, the industry would go belly-up or move elsewhere. It had happened all across the country before. Now it was going to happen in Oregon and Washington too.

So if the forests were going to run out anyway, why not stop cutting a few years earlier? That’s all the association wanted—just leave some of the land as it was. The number of people who would enjoy these forests would be far greater than the number who would benefit from cutting every last tree. That would be the greatest good for the largest number.

Saul was an ardent conservationist who had spent most of her life in logging towns. After graduating from the University of Oregon, she had gotten a temporary job with the Fish and Wildlife Service in Malheur County, in the southeast corner of Oregon. Then a permanent job had opened up in Longview. She figured that the hiking would be better near Mount St. Helens, with Mount Adams just to the east and Mount Rainier to the north, and the hiking was better, despite all the timber cutting. But Mount St. Helens was the only volcano in the entire state—almost the only volcano in the entire northwest—that wasn’t within a national park, a wilderness area, or a recreation area. Unless people like her did something, the area around the mountain would be ruined.

What made the whole thing especially frustrating is that they had to fight not just the timber companies but the Forest Service too. Sometimes it seemed that the Forest Service wouldn’t be happy until the entire Gifford Pinchot National Forest was nothing but a sea of stumps. She’d once seen an aerial photograph of the area around Mount St. Helens, and the national forest land east of the mountain was as cutover as the Weyerhaeuser land west of the mountain. The Forest Service was completely opposed to the idea of a monument. A monument would keep the Forest Service from building roads and making timber sales in their land, and they wanted nothing to do with it. “Their land,” Saul thought bitterly. The national forests were supposed to belong to the people, not to the Forest Service. But the Forest Service acted as if people were the threat, not the timber and mining companies.

She’d gotten to know Don Bonker, the US representative for Washington’s third district. Whenever he came to Longview to give a talk or meet with his constituents, Saul made sure to be there so she could tell him what the association was trying to do. He was sympathetic to what they wanted. He’d supported the land swap between Weyerhaeuser and the Forest Service that saved Miners Creek. But he had other constituents he needed to please too. Whenever she met with him, she got the sense that he just wanted to tell her, Don’t worry. Everything will be fine. But everything wouldn’t be fine without his help.

Lots of people supported the association’s goals, at least in principle. In Saul’s clippings file, she had the editorials the Longview Daily News had written about their cause, along with all the letters the paper had published when it invited readers to comment on whether roads and logging should be permitted in the Spirit Lake basin. Almost all of the respondents said no, even the loggers and millmen who wrote in. “Just for a few greedy people to cut those beautiful trees: no, no, no,” wrote a papermaker in town. “Shut off the timber cutters until they show concern for the public. They could care less,” said a civil engineer. “If we let people like George Weyerhaeuser totally devastate this land, we are defeating ourselves,” a local carpenter wrote. More and more people were in the woods every year. They knew what they were losing. They weren’t going to let Weyerhaeuser and Burlington Northern take it all away from them. The Mount St. Helens Protective Association just needed to get them involved.

Saul and McRae had a plan. They would lead a series of hikes through the national monument the association had proposed. They would show people what was at stake. The first one was planned for Saturday, May 10. They would lead a group up the Green River valley. That’s where the conflict was greatest. They’d go from Weyerhaeuser’s clearcuts on the lower part of the river to the old-growth forest north of the volcano. It was one of the most magnificent forests left in the entire Northwest, maybe in the entire country. No one could walk among those trees and believe that they should all be cut down. If the association could just get more people into the woods, they could stop Weyerhaeuser and the Forest Service. But time was running out. If they didn’t stop the logging soon, there would be nothing left to save.

AT 7:30 IN THE MORNING ON MAY 10, 1980, SAUL DROVE FROM HER home on Nineteenth Street toward the town square in the middle of Longview. She passed the bronze bust of Robert Long in the middle of the square, his stern, bespectacled face gazing east toward the forested hills on the other side of the Cowlitz River, and parked on the north side of the square at the Longview Public Library, a gorgeous Georgian building that Long had built in the 1920s for his employees and their families.

About twenty people were gathered in the library parking lot. Russ Jolley was there, who’d been very active with the Mount St. Helens Protective Association, along with Hermine Soler; Sarah Detherage; Jim Fletcher; Arlene Walker; Harry Deery and his wife, Ruth; Jean Lancaster; Russ Maynard; Mary Ellen Covert; and eight or ten others. Many were members of the Willapa Hills Audubon Society or the Mount St. Helens Hiking Club, people who largely knew what was at stake. But Saul didn’t recognize some of the other people in the group, and the association needed new recruits if it was going to make progress.

She and McRae had thought about calling off the hike when Mount St. Helens started acting up in March. But McRae had called the Forest Service, and the person on the phone said that the Green River valley was not in the red or blue zones, so they were free to go there if they wanted. The valley was ten miles and three ridgelines to the north of Mount St. Helens. No one was expecting trouble that far from the volcano.

They divided into separate cars and headed north on Interstate 5 to Castle Rock, where they turned off the interstate onto the Spirit Lake Highway. They followed the highway past Silver Lake, formed just 2,500 years ago by a massive mudflow that dammed the Toutle River, and drove through the town of Toutle. Just past the cluster of stores and campgrounds in Kid Valley, they turned off the Spirit Lake Highway onto Road 2500, a good gravel road that paralleled the Green River north of the Toutle. They were on Weyerhaeuser land now; Road 2500 passed through clearcuts, hillsides newly planted with young trees, and second-growth forests that were almost ready to cut again. A bit more than twenty-five miles from the turnoff, Road 2500 crossed the Green River before heading up the hill toward Fawn Lake, and there they parked in a small clearing on the north side of the bridge. They pulled on rain parkas and wool hats—it was a cloudy and cool day, only about 50 degrees, and though it wasn’t raining at the beginning of the hike, the rain could start anytime. Then they headed up Trail 213.

The area right around the parking spot had been cut over and was surrounded by scrubby second-growth trees. But as soon as the group started up the trail they entered the old-growth forest of the Green River valley. Immediately the forest floor around them opened up, so they could see through the trees to a great distance, and the canopy rose far overhead, so that they had to stop walking and look up to see the treetops. Around them rose the massive boles of Douglas firs and western red cedars, trunks so large that five people joining hands could not encircle them. The trees seemed to hold up the roof of the sky, so that walking through them was like being inside an immense building too grand to be fully seen. The color of the trees around them darkened, even as the forest itself lightened, as if the air had acquired a crystalline green hue. The forest contained trees of all ages, seedlings, saplings, supplicants reaching toward the light overhead, and all around them were the decaying trunks of fallen giants, many of them bearing new trees on their rotting surfaces. The variety and abundance of life were everywhere evident: shelf fungi on the sides of trees, moss draped across branches, the beetles and centipedes of the trail, the birds arcing from tree to tree, the squirrels chattering on overhead limbs, elk tracks in the mud, and all the unseen life of the forest, the fish in the river and the animals underground and the decomposers silently returning the fallen logs to the soil. Nothing really dies in such a forest. One living thing blends seamlessly with the rest. The forest itself is alive, its constituent parts just the passing clouds of a summer day.

Many naturalists have compared old-growth forests to churches, but that analogy doesn’t quite work in a place like the Green River valley. If a church represents the efforts of the devout to invite God to join them in a place created by people, then a forest is a place where God already resides, and people can choose to recognize or ignore His presence. Saul felt the presence of God in a forest like this just as much as in the Catholic church back in Longview, but in a different way. It was impossible to imagine a forest like this in which God did not exist.

That wasn’t the case for the second-growth forests they’d driven through on the way there. Those were the creation of men—genetically honed, even-aged stands planted by humans to meet the needs of humans. Old-growth forests met no needs. They simply were, in a way that bore no questions about purpose or value. They could not be created by men. They could not even be understood by men. They had too many parts that were interconnected in too many ways. Change one part and everything else would change, but in ways that were unpredictable and often inexplicable. This unpredictability removed such forests from the realm of human perspectives and values. The forest did not need to justify or explain itself. It existed outside of instrumental human considerations.

From her father, Saul knew the value of the wood through which she walked. The timber along this river was worth many millions of dollars. To a lumberman, leaving these trees there to grow and die was like walking past a pile of money and leaving it untouched. It made no sense to leave this timber when it could pay for houses and trucks and college educations so children wouldn’t have to risk their lives working in these woods. The Green River valley was not easy to reach: a twenty-mile drive up a gravel road from the west, an equally long drive up an equally slow road from the east. Most people would never see this valley in anything other than photographs. They wouldn’t have the patience to drive all the way there and hike up a trail with no views or alpine lakes waiting at the end.

But wasn’t that the idea—just to have it there, to know that it existed? People did not need to go there for the forest to have value. It would be a place of intrinsic value, a reminder of what had been and what could be again someday. People could draw inspiration from it when they needed inspiration. It would be waiting, inattentive to human needs yet serving them just the same.

Convincing people to value these woods was not easy, Saul knew. It took time and experience to appreciate these forests for what they were. Most people would see these magnificent trees simply as wood. Even longtime hikers, when tired or distracted, could just want to get back to their cars. Weyerhaeuser owned the land through which they were walking, even though it was in the national forest, and pressures were growing to cut the trees. The association had proposed that the valley be placed in a national monument so that the old growth would be saved. But to do that the association would have to give up ground elsewhere. There seemed no way to balance the needs of one against the other without giving up something irreplaceable.

The group hiked in clumps up the Green River valley, some talking, some walking silently. Partway up the trail they passed an old elk hunter’s shack surrounded by fuel cans, dirty dishes, silverware, liquor bottles, beer cans, and plastic containers. Saul and McRae had complained to the Forest Service about the shack, but the agency was reluctant to do anything about it. The hunters who used the shack would object if the Forest Service removed it.

The hikers continued through the woods. They were intending to walk to the falls near the Minnie Lee mine—one of several old mines along the trail that had never panned out—and then return to their cars.

But one member of the group, Harry Deery, a retiree who had climbed Mount St. Helens twenty times and knew the area as well as he knew his own backyard, was deeply uncomfortable. Mount St. Helens is not visible from any part of the Green River. The ridge south of the valley rises steeply from the river and blocks any views in that direction. But Deery could sense the unseen volcano behind the looming green precipice. He knew that Saul and McRae had gotten assurances from the Forest Service that they were hiking in a safe place. But how could anyone know for sure that this valley was safe? He’d read an article in the paper saying that everything within fifteen miles of the volcano could be incinerated in an eruption, and they were well within that range. He’d seen paintings of historic eruptions—the people of Pompeii bombarded by falling lava from Vesuvius, the explosion of Krakatoa, Paul Kane’s painting of Mount St. Helens erupting in 1847. With each step they were traveling farther away from their cars, farther away from safety, farther away from their only means of escape.

Eventually Deery couldn’t stand it anymore. He told his wife that he was going back. She laughed at him—she wasn’t about to give up this hike after driving all this way. But Deery couldn’t continue. He turned around, walked by himself back to the cars, and sat waiting until the others returned.

ON THURSDAY, MAY 15, COWLITZ COUNTY SHERIFF LES NELSON tried one last time to talk Harry Truman into leaving the Mount St. Helens lodge. He drove up the Spirit Lake Highway and parked outside the lodge with his motor running and the car pointed down the Toutle River valley. That Thursday was cloudy and cool, so Nelson didn’t have to look up at the ash-draped bulge hanging off the north face of the mountain. But he could feel its presence behind the clouds, and it made the air heavy and oppressive. He knew that the weather forecast called for the weekend to be clear. Good weather meant that a lot more people would be around the mountain after a long wet spring, which would mean a lot more work for him and his deputies.

Inside, Truman was triumphant. A few days earlier he’d gotten a letter from Dixy Lee Ray. If he was ever thinking about leaving before, he certainly never would now. The letter read:

Your independence and straightforwardness is a fine example for all of us, particularly for senior citizens.

When everyone else involved in the Mount St. Helens eruption appeared to be overcome by all the excitement, you stuck to what you knew and what common experience and sense told you. We could use a lot more of that kind of thinking, particularly in politics.

I get a fair amount of criticism for calling things the way I see them. I’m glad someone like yourself got credit for the same approach.

Why didn’t the governor just come down and rip the badge off Nelson’s chest? She was the one who was supposed to be in charge of public safety. If the governor wouldn’t protect these people, then no one could. Truman had been hinting that he was ready to give up his vigil. He had told friends that he was tired of the earthquakes and couldn’t sleep. To one, he had said, “The only reason I’m here is because they let me stay.” A few days earlier, the sheriffs had scrambled to send a helicopter to the lodge when a Seattle news crew told them that they’d found Truman “in a broken-down and emotional state” and that he wanted to leave. But by the time the helicopter arrived, Truman had changed his mind. It would be hard for Truman to quit now, Nelson knew. He had painted himself into a corner with his bluster. People were expecting him to hold out against everyone telling him to go.

Nelson pleaded with Truman to leave but quickly realized it was futile. He said goodbye, got in his car, and drove as fast as he could back down the Spirit Lake Highway.

• • •

The next day, the concerns of the loggers working around Mount St. Helens came to a head. The geologists were saying that a landslide was inevitable, but the loggers were still working right next to the mountain. Even if a landslide affected just the valleys, those were the roads they needed to escape an eruption. One logger had already walked off the job on Thursday. More were threatening to do so the following week.

Friday morning, a safety representative for the International Woodworkers of America local named Joel Hembree drove up the south fork of the Toutle to talk with a group of about fifty disgruntled loggers who were working within five miles of the mountain’s base. Several weeks earlier the company had promised that it would develop evacuation plans for each logging district. But in many cases, Hembree found, either the plans had not been developed or they had not been communicated to the crews.

Still, Hembree urged the loggers not to walk off the job. “We got the best experts in the world,” he told them. “Supposedly you’re going to get two hours’ notice, but all I can tell you guys is if it blows, it blows. Who’s to say it won’t happen tomorrow, or ten years down the line?”

• • •

Also on Friday, John Killian called LeRoy Baine, who had been the best man at his wedding, to see if he and his wife wanted to come fishing with Christy and him over the weekend. The state had kept many of the lakes and rivers around Mount St. Helens closed to see what would happen with the volcano. But now that the eruptions had quieted down, it had opened them all, except for the lakes in the red zone. The fishing was bound to be great up there, John told LeRoy. No one had been up there all spring. The fish were just waiting for them.

But LeRoy’s wife, Elna, had a cold; the Baines couldn’t come. It was just as well. John and Christy were trying to start a family. If they were alone, they would have more time together.

Saturday morning, John and Christy stopped by the house where John’s sister and her husband lived to pick up some fishing gear. John had always been close with his three sisters. He was their only brother. He had a responsibility to look out for them.

Charlene asked where he and Christy were going.

“They’ve opened Fawn Lake,” John replied. “We’re going there.”

“Isn’t it a bit close?”

“It’s okay, Char.”

Only in retrospect did Charlene wonder why she hadn’t objected more strongly to John’s plans. But there was no reason to be worried. The Weyerhaeuser Company had told their father that the loggers were safe working near the mountain, and Ralph had passed that information on to his crew and to John. The worst that was expected was flooding in the valleys and maybe some ashfall. Fawn Lake was nine miles and three ridgelines away from the volcano. They would be fine.

By this point, it had become obvious to local law enforcement personnel that the red and blue zones Dixy Lee Ray had established at the end of April were inadequate. The woods on the western, northwestern, and northern sides of the mountain were full of people who were working, camping, fishing, or trying to get a good look at the volcano. Because they were not inside the red or blue zones, police officers could not cite or fine them and had no authority to keep them out of the area. Weyerhaeuser had always kept most of the gates to its logging roads open, partly so loggers could get in and out of the woods quickly and partly because the company had a policy of keeping its lands open to the public. It was a generous act on the company’s part, but now it was causing great headaches for the sheriffs and their deputies.

Les Nelson and the other sheriffs had been working with the state, the Forest Service, and Weyerhaeuser on an expansion of the restricted zone, and by May 15 all the parties had agreed on a proposal. It would extend the blue zone eleven and a half miles to the west and seven and a half miles to the north. It also would move the roadblock farther down the Spirit Lake Highway, to right above Weyerhaeuser’s Camp Baker. The new proposal would actually make it easier for loggers, reporters, and property owners to get into both the blue and red zones. The media would be allowed into the red zone on helicopters so long as they did not land above the tree line. Loggers could get permits to log in the red zone, whereas before they had been allowed only in the blue zone. The main effect of the new zones would be to get the public out of the areas west and north of the volcano. The sheriffs would have legal authority to cite people who entered the area. And Weyerhaeuser would get the cars and campers off its logging roads and out of the way of its trucks.

That Thursday, Nelson sent a memo to the head of Washington State’s Department of Emergency Services outlining the proposal. Extending the blue zone and moving the roadblock would place “the public farther away from the mountain,” Nelson wrote, and would bring “the Governor’s executive order into realistic alignment with existing geological conditions.” Other sheriffs and public officials working in the area sent similar letters, citing the Geological Survey’s warnings that the bulge eventually would give way.

State officials knew that the local sheriffs were right. But they delayed for a day while typing up the order and making sure that Weyerhaeuser had bought into the plan. The sheriffs were ready on Friday to move the roadblock and post the new blue zone before a weekend of warm and sunny weather. But the order never came. Not until Saturday morning did officials hand-deliver the order to the governor’s office for her signature. By then, Ray was attending a Rhododendron Day parade in Port Townsend on the Olympic Peninsula. The new blue zone would have to wait until Monday.

• • •

Also by the third week of May, the owners of the eighty or so cabins a mile and a half west of Spirit Lake were in open revolt. Their cabins were inside the red zone and strictly off limits. They couldn’t get to their property to remove personal items, do maintenance, or feed the pets they’d left behind. On Friday, May 16, a group of owners vowed that they would form a caravan the next day and drive to the roadblock on the Spirit Lake Highway to protest their exclusion. Rumors circulated that some planned to arm themselves and run the roadblock. The Washington State Patrol assigned eight extra cars to keep order.

When the owners assembled in the Toutle High School parking lot to begin the caravan Saturday morning—each wearing sky-blue sweatshirts bearing a drawing of Mount St. Helens and the words “I own a piece of the rock”—they learned that the governor would allow them to go to their cabins if they filled out a waiver and left the area by six that evening. Bending over the hood of a state patrol car, thirty-five people completed a form that absolved state and county agencies of responsibility for anything that might happen to them.

With two police cars in front and one behind, the caravan made its way up the Spirit Lake Highway to the cabins, accompanied by a procession of reporters. A state patrol plane flew overhead to keep an eye on the mountain.

The cabins were largely as their owners had left them. A thin layer of ash covered the ground. As predicted, skies had cleared Friday afternoon, and that Saturday was sunny and warm. Across the Toutle the cabin owners could see the ash-shrouded mountain, simultaneously grand and ominous in the afternoon sunshine. They loaded leather chairs, photos, fishing equipment, and other possessions into their pickups. One owner left a ten-pound bag of cat food open for her cat.

That afternoon, Rob Smith and his girlfriend Kathy Paulsen left the lodge the Smith family owned near the cabins and drove the rest of the way up the Spirit Lake Highway to see their friend Harry Truman. Truman was watering his lawn when they arrived, getting the lodge ready for summer tourists. Smith helped Truman sharpen his saws so he could cut more firewood. A police sergeant who was also visiting Truman gave him a bundle of mail, including letters from schoolchildren who had read about his refusal to leave the mountain. Truman’s eyes teared up when he saw the letters. Some of his visitors that afternoon thought that he was just being sentimental; others, that the strain of holding out at Spirit Lake was getting to him.

As Smith and Paulsen prepared to leave, Truman followed them to their truck. Truman leaned in the window and said that he would see them the next day—he was planning to come to Castle Rock to buy primroses to plant in the garden. Smith and Truman both got teary when it came time to leave. “Oh, c’mon,” said Truman, “let’s keep a stiff upper lip.”

By six p.m., everyone in the caravan had packed up their belongings. The state troopers made sure everyone was in their cars, escorted them back down the highway, and locked the gate behind. The governor had said that another caravan could travel to the cabins Sunday morning. In the small towns west of Mount St. Helens and up and down Interstate 5, property owners were making plans to retrieve their remaining possessions the next day.

• • •

That Saturday morning, the geologists in Vancouver had their usual staff meeting. Now that the volcano had calmed down, many were away that weekend. Crandell was back home in Denver. Mullineaux was in California attending his daughter’s college graduation. But the geologists and seismologists were still monitoring the volcano carefully. The bulge couldn’t keep expanding forever.

At the staff meeting the geologists discussed a problem. For the past two weeks, a graduate student whom Dave Johnston had hired named Harry Glicken had been staying in the small white trailer parked at Coldwater II. His job was to monitor the bulge and issue a warning if he saw any sign of an avalanche or eruption. But Glicken had to leave for California that evening to talk about the graduate work he was starting in the fall, and the Geological Survey needed someone else at Coldwater II to keep an eye on the volcano. A geologist named Don Swanson, who had been working at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory on the Big Island before Mount St. Helens became active, agreed to go. But after the meeting, Swanson sought out Johnston in a hallway. Could Johnston fill in for him that evening? Swanson had a graduate student from Germany visiting, and he wanted to see the student off on Sunday morning. Swanson would replace Johnston as soon as the student was gone.

Johnston was much more worried than either Swanson or Glicken about spending time near the volcano. After his close escape from Mount Augustine, he knew that being near a volcano could be deadly. And he’d never liked the looks of Mount St. Helens. It was doing things that volcanoes weren’t supposed to do, things that were difficult to understand. At this point, the geologists agreed that the bulge had to be the result of magma welling up inside the volcano and pushing on the mountain’s north flank. But if that was so, why hadn’t Johnston detected higher levels of sulfur emerging from vents on the volcano’s sides? It was as if the magma were somehow bottled up and unable to escape to the surface. But did that mean that the mountain was about to erupt or that it was more stable than they’d thought?

Despite his misgivings, Johnston agreed to fill in for Swanson that night as long as Swanson would replace him on Sunday. Later that day he drove his tan government-issued Ford Pinto station wagon up the Spirit Lake Highway. Johnston had never been to Coldwater II, and he missed the turnoff to the observation post and continued up to Timberline. There he boarded the helicopter the geologists had been using for their research and flew high onto the side of the volcano. He jumped out and quickly measured the temperature of a steam vent. It was only 190 degrees Fahrenheit, which Johnston judged a “poor temperature” for a fumarole. But then rocks began falling all around him as an earthquake shook the mountain. Johnston dashed back to the helicopter and flew away.

Later that afternoon, two young scientists with the Geological Survey drove up to Coldwater II to visit with Johnston and Glicken, who had not yet left for California. Mindy Brugman and Carolyn Driedger were studying glaciers on Mount St. Helens and other western volcanoes. Brugman had become an expert with the device the geologists were using to measure the distance between Coldwater II and the bulge, and she wanted to see if Johnston was having any trouble with it. He wasn’t, so Brugman and Driedger simply settled in to enjoy a beautiful Saturday afternoon. They had seen other cars and trucks on the ridgelines as they’d driven in, mostly people who had taken logging roads to get near to the volcano. But the volcano seemed quiet. Even the growth of the bulge had slowed slightly. The four geologists took turns photographing one another in the director’s chair outside the white trailer.

As the sun dropped toward the western horizon, Brugman and Driedger asked if they could spend the night on the ridge. They had their camping gear in the back of Brugman’s truck. They wouldn’t be any trouble. But Johnston insisted they leave.

“Why?” asked Driedger. “Rocky’s showed that nothing has ever happened up on this ridge.”

“That doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen,” Johnston said. “When that landslide comes down, it could come all the way across that valley and up over the top of this ridge.”

“But the mountain’s five miles away,” Driedger objected.

“It could happen.”

About seven that evening, Brugman and Driedger threw their stuff in the pickup and headed back down the logging road. Brugman remembers that she was surprised by how many animals kept jumping into the roadway.

Before he went to sleep, Johnston got on the radio with a geologist named Dan Miller in Vancouver. Miller told him that the armored personnel carrier was on a flatbed truck traveling down Interstate 5 and would arrive the next day.

“Are you serious?” asked Johnston, who had not heard about the plans for the personnel carrier.

“I’m serious,” Miller replied.

“Are they going to provide ammunition?”

“That’s negotiable at this point,” said Miller.

• • •

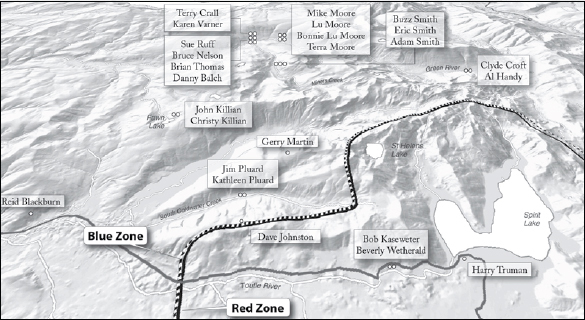

By that evening, Harry Truman was the only person left on the shores of Spirit Lake. But in a ten-mile by thirteen-mile rectangle north of the volcano, more than twenty other people were also settling down for the night. If the blue zone had been extended to the north and west, as the local sheriffs were advocating, most would not have been there. But with the extension order sitting unsigned on Dixy Lee Ray’s desk, none of them was doing anything wrong.

People north of Mount St. Helens on the evening of Saturday, May 17, 1980

In the cabins west of Spirit Lake, the state patrol had ushered everyone back down the Spirit Lake Highway except for Bob Kaseweter, a thirty-nine-year-old geochemist, and his girlfriend, Beverly Wetherald. They had a permit allowing them to stay in their cabin, even though it was in the red zone. They both worked for the Portland General Electric utility company, and Kaseweter had convinced the authorities to let him conduct research on the mountain from his cabin. He had rigged up a battery-run seismograph, with the graph paper disappearing through a hole in the floor into the basement. He also was photographing the bulge from his deck, documenting the progressive widening and lengthening of the cracks in the ice.

Some people weren’t happy about the couple being allowed to stay. Other cabin owners complained that Kaseweter’s studies were an excuse to avoid the red-zone restrictions. “It’s a serious study,” Kaseweter retorted. “I’m not using it as an excuse. It’s the chance of a lifetime.”

Kaseweter and Wetherald had driven up the Spirit Lake Highway Friday afternoon in Kaseweter’s orange Volkswagen but had gotten stopped by a state trooper at the roadblock. “I’m doing geology at my cabin,” Kaseweter said. “This is my secretary.”

The trooper got on the radio to check out his story. About then, Harry Truman arrived at the roadblock in his white pickup.

“Everyone says you know about the volcano,” the trooper said to Truman while waiting to hear back on the radio.

“Hell, I’ve no idea what the damn thing will do,” said Truman.

The radio came on telling the trooper that Kaseweter and Wetherald could go, but not in their car. “Okay to pedal up?” asked Kaseweter, lifting a bicycle from its rack on the Volkswagen. He could leave the car at the roadblock and pick it up when they left.

“How’m I going?” asked Wetherald.

“I’ll give you a ride,” said Truman. “Jump in.”

• • •

Coldwater II was high on the ridgeline a mile northwest of Kaseweter’s cabin. From there, Johnston and the other geologists looked across the broad, wooded valley of the Toutle River to the ash-covered bulge on Mount St. Helens’s northern flank. But they weren’t the only people on nearby ridgelines that evening.

Washington State did not have the funds to pay for observers who could warn surrounding communities of an impending eruption, so it turned to a volunteer organization. The Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service had helped the state previously with fires and floods. Now the organization had agreed to station ham radio operators with mobile rigs around the mountain to monitor its activities.

Earlier on Saturday, Gerry Martin, a sixty-four-year-old volunteer ham radio operator from Concrete, Washington, had driven his twenty-six-foot green-and-white Dodge Superior motorhome up a rough gravel road and onto the ridge just north of the Coldwater II post. A retired US Navy radioman, Martin parked in a clearcut a bit higher than Dave Johnston, so he could see, across the valley containing South Coldwater Creek, both the mountain and the trailer in which Harry Glicken had been sleeping the past two weeks. Other members of the radio network also were stationed around the mountain that Sunday morning, but Martin was the closest.

One other person was on a ridgeline north of the mountain that evening. At the Coldwater I observation post two miles west of Johnston, photographer Reid Blackburn was taking his last photographs of the day. Blackburn, a twenty-seven-year-old photographer for the Vancouver Columbian newspaper, was participating in a project arranged by Fred Stocker, a freelance photographer for National Geographic magazine. Blackburn’s job was to trigger by remote control a series of cameras stationed around the mountain. The original plan called for six cameras, but only two turned out to be available—the others were lent out to cover the Kentucky Derby. One camera was set up with Blackburn at Coldwater I. The other was on the side of Mount Margaret north of Spirit Lake.

Blackburn was popular in the Columbian newsroom. He liked to play jokes on his officemates, like filling the photo editor’s coffee cup with cigarette butts during an anti-smoking campaign. He had thick brown hair and a well-kept beard and wore a pair of square black glasses. The Columbian had been more cautious than other media outlets, which had been playing up the story through stunts like flying reporters and photographers to the rim of the crater. Blackburn’s location was supposed to minimize the danger while giving him a clear view of the volcano.

Blackburn was perfectly suited for the job. He was a skilled photographer who thrived in a place of great natural beauty like southwestern Washington. He also was an outdoorsman who often camped and hiked around Mount St. Helens. He and his wife, who worked in the advertising department of the Columbian, had gone cross-country skiing there on March 23, three days after the first earthquake but before the area around the mountain was closed. He was a licensed ham radio operator, which was required to operate the radio-controlled cameras. And he was accustomed to dangerous assignments—a few months earlier, he had photographed a wrecked tanker car leaking ammonia gas, betting that the wind wouldn’t change directions and coming back with dramatic photos of the tanker’s engineer and brakeman being rescued.

On Saturday, Stocker and the driver he had hired for his National Geographic assignment, a man named Jim McWhirter, spent much of the day with Blackburn. But McWhirter was restless. “The whole day I’d just been on edge,” he later recounted. “I don’t know what the feeling was. Now I attribute it to the Holy Spirit telling me to watch out, even though I didn’t really believe in God at the time. I just had to do something.” Blackburn told them that he was going to stay; he had an obligation to trigger the cameras. Finally Stocker suggested that he and McWhirter drive to his girlfriend’s restaurant near Olympia for a steak and lobster dinner. McWhirter quickly agreed, but he said that he wanted to be back by eight the next morning, since he had no desire to spend the entire next day with Stocker and his girlfriend. That night they ended up “partying pretty hard,” McWhirter said, and didn’t get to bed until three a.m.

On Thursday, Blackburn had talked by phone with his wife, Fay, about the project. Placing a phone call from Coldwater I was complicated. Blackburn had to have an operator patch his ham radio through to the phone network, and regulations limited phone calls to just three minutes. In their brief time on the phone, Blackburn and Fay talked about the project. The newspaper was about to shut it down. The remote-controlled cameras were producing essentially identical photographs, and nothing seemed to be happening with the volcano. But he would stick it out over the weekend, Blackburn said. He enjoyed camping at Coldwater I. He could stay warm near the fire barrel the geologists had left behind. He listened to ’70s music on a cassette tape he’d made.

After Stocker and McWhirter left on Saturday, Blackburn placed another call to Fay. She heard the phone ringing just as she was leaving the house, but by the time she answered, the caller was gone.

• • •

After stopping by Charlene’s house, John and Christy Killian drove up the Green River and through a tangle of logging roads that John knew as well as he knew the streets of Vader. Fawn Lake rests in a classic alpine cirque carved by an Ice Age glacier into the north side of the ridge, where the Killians were camping. It has the shape of an amphitheater, with a high wood-covered slope to the south. On the north end of the lake, near its outlet, the land drops off into the valley that cradles Shultz Creek. Weyerhaeuser had heavily logged the area around the lake, but the steep slopes of the cirque and the area around the lake’s outlet to Shultz Creek, where the Killians camped, was still covered with old-growth trees.

The Killian family had been coming to Fawn Lake for decades. It was one of their favorite places to camp and fish in all of southwestern Washington. Before they went to bed that evening, John and Christy undoubtedly enjoyed the firm, fresh flesh of eastern brook trout.

Northeast of Fawn Lake, Edward “Buzz” Smith and his two sons—Eric, age ten, and Adam, age seven—also were getting ready to crawl into their tent. Smith was a Weyerhaeuser logger from Toutle who knew the backcountry well. He and his sons had driven up Road 2500 to where it crosses the Green River and heads into the high country. There they parked in the flat area where Susan Saul and her associates had parked the week before. They hiked up the Green River a mile or so. Then they crossed the Green on a log bridge and followed Miners Creek to the base of a large bluff. They set up their tent just to the west of Black Mountain, one of the highest peaks in the country north of Mount St. Helens.

• • •

Back on the Green River, three separate groups had set up camps that Saturday night.

Farthest upriver, Clyde Croft, thirty-seven, and Al Handy, thirty-four, had laid out their sleeping bags beneath a blue plastic tarp. They were friends who worked together in a warehouse of the West Coast Grocery Company in Tacoma. They were very different men. Handy was quiet and introverted; Cross, outgoing and rambunctious. But they enjoyed each other’s company, both at work and when they got together after work.

For nearly a year they had been planning a horseback-riding trip north of Mount St. Helens. Now that the first nice weekend of the year had arrived, they had decided to go. On Friday, Croft had borrowed a pickup truck and horse trailer to cart two of his horses up the mountain. After finishing work about midnight on Friday, they headed out. They drove east on Highway 12 to a town called Randle halfway between Mount Rainier and Mount St. Helens. There they turned south and followed a rough set of logging roads to Ryan Lake, a small, clear lake about twelve miles north-northeast of the volcano. To the south of the lake, the Green River descends from its origins in the high country north of Mount St. Helens. To the west, the Green heads toward the Toutle, the Cowlitz, the Columbia, and the sea.