KEITH STOFFEL COULDN’T BELIEVE HIS GOOD LUCK. THE DEPARTment of Natural Resources geologist and his wife, Dorothy, had driven from Spokane to Yakima the previous day so he could give a lecture about Mount St. Helens at a gem and mineral show, and the weather forecast had promised that Sunday would be clear. He had called the airport before the lecture and reserved a Cessna, and Sunday morning he, Dorothy, and the pilot, a man named Bruce Judson, were flying through a cloudless sky toward the glistening white peak on the horizon. Almost everyone else in the department had already flown over the mountain, but Keith, who was twenty-seven, and Dorothy, age thirty, a consultant for a private geology firm, had not yet seen it.

Dorothy had never been on a small plane before, and she had been terrified that morning before they took off. “Do you like to fly?” she asked Judson as they were walking across the tarmac. “It’s just like any other job,” said the twenty-three-year-old, trying to reassure her. “It gets boring after a while.”

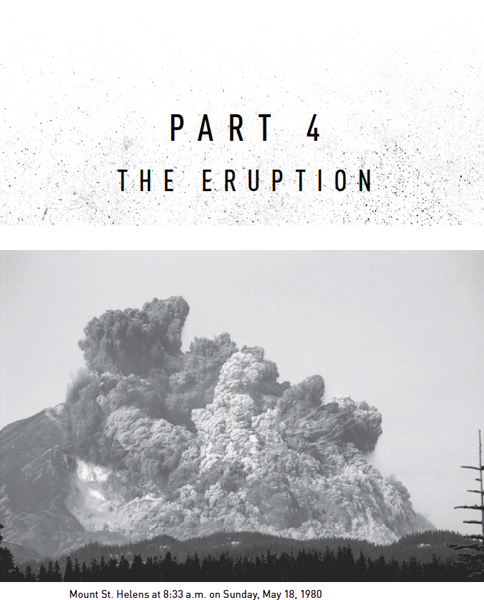

They were on their fourth pass over the north rim of the crater, flying west to east, when Keith noticed something moving. “Look,” he said, “the crater.” Judson tipped the Cessna’s right wing so they could get a better view. Some of the snow on the south-facing side of the crater had started to move. Then, as they looked out the plane’s windows, an incredible thing happened. A gigantic east-west crack appeared across the top of the mountain, splitting the volcano in two. The ground on the northern half of the crack began to ripple and churn, like a pan of milk just beginning to boil. Suddenly, without a sound, the northern portion of the mountain began to slide downward, toward the north fork of the Toutle River and Spirit Lake. The landslide included the bulge but was much larger. The whole northern portion of the mountain was collapsing. The Stoffels were seeing something that no other geologist had ever seen.

A few seconds later, an angry gray cloud emerged from the middle of the landslide, and a similar, darker cloud leapt from near the top of the mountain. They were strange clouds, gnarled and bulbous; they looked more biological than geophysical. The two clouds rapidly expanded and coalesced, growing so large that they covered the ongoing landslide. “Let’s get out of here,” shouted Keith as the roiling cloud reached toward their plane. Judson put the Cessna into a steep dive to pick up speed. He redlined the airspeed indicator; any faster and he would rip off a wing. Keith noticed that the cloud was extending to the north and east. “Turn right!” he yelled.

Now flying south, they began to outrun the cloud. From the front seat, Dorothy turned and looked back at the volcano. A column of dark ash, like a solid object, rose from the mountain higher than she ever thought possible. It was shot through with lightning—pink and purple and yellow. Far overhead, the ash had spread into an anvil shape and was beginning to blow east. They heard no sounds other than the whining of the Cessna’s engines. It was as if the volcano were erupting silently.

HARRY TRUMAN, BOB KASEWETER, AND BEVERLY WETHERALD

THE THREE PEOPLE NEAREST MOUNT ST. HELENS—HARRY TRUMAN in his lodge on Spirit Lake, and Bob Kaseweter and Beverly Wetherald in their cabin a mile downstream—were close enough to hear a rumbling from the mountain as its north flank began falling toward them. But before the avalanche reached them, the expanding cloud that the Stoffels had seen from the plane overtook the falling earth and raced ahead. The cloud sped down the flank of the volcano, ripping the forest from the mountainside as it passed. When the cloud hit the resorts and camps around Spirit Lake and the cabins on the Toutle River, it blew the structures to bits.

A few seconds later, the avalanche reached Spirit Lake and the Toutle River. It buried the lodge and cabins under hundreds of feet of steaming stone, earth, ice, and mud. Harry Truman, Bob Kaseweter, and Beverly Wetherald were dead before they could have known what was happening.

ON THE RIDGE OVERLOOKING THE TOUTLE RIVER, DAVE JOHNSTON had been awake almost since the sun rose at 5:36 that morning. He had already measured the distance to the bulge three times, registering first a slight expansion and then a slight contraction.

“What are things like up there?” Johnston’s colleague Bob Christiansen asked over the radio.

“It’s very nice,” said Johnston. “You can see the mountain clearly. There are no clouds.” They talked for a moment about Johnston’s gas-monitoring data. “Okay, that’s all I have to say,” Johnston said. “Coldwater, clear.”

Johnston was watching the mountain when the landslide began. He must have watched it for at least a few seconds. The landslide consisted of three blocks that slid away from the mountain. When the first block dropped toward the Toutle River and Spirit Lake, it exposed the top of a pocket of magma that was partly embedded in the landslide’s second block. This intruded magma had been pushing outward under the mountain’s north flank, creating the bulge. But, as Johnston had suspected, the overlying rocks had sealed the magma up tight, heightening the pressure inside the mountain. When the landslide released that pressure, the water in the magma flashed into steam. That’s what created the two rapidly expanding clouds that the Stoffels had seen from their plane. The magma pocket was like a steam boiler. For almost three months the pressure inside that boiler had been building. Now the boiler had failed.

Technically, the explosion that swept out of Mount St. Helens that morning is known as a pyroclastic density current. Most geologists refer to it simply as “the blast,” though some prefer the term “surge,” contending that it was not really an explosion. The blast cloud accelerated as it spread, drawing heat energy from the fragmented magma it contained. Inside the cloud were ash, pumice, lava blocks, snow, ice from the overlying glaciers, tree fragments, soil swept from the ground, and boulders as big as cars. It expanded at speeds of hundreds of miles per hour, but in a particular way. As Dave Johnston and Barry Voight had feared, Mount St. Helens did not explode straight up. It exploded to the side, in the direction of the bulge. The avalanche created an amphitheater-shaped gouge in the mountain, and this gouge channeled the blast to the northwest, north, and northeast. It was as if the blast had emerged from the muzzle of a cannon pointed directly at Coldwater II.

When Johnston saw the north flank of the mountain give way, he flipped on the radio. “Vancouver, Vancouver! This is it!” he said. Most people have interpreted this statement to mean that Johnston realized that the big eruption, the one he had feared all along, had finally occurred. But Johnston was a scientist with an assignment, and his voice was excited, not fearful. He was there to monitor the volcano for precursors that could signal the beginning of a landslide down the Toutle River valley. He was probably trying to tell his fellow geologists in Vancouver that the landslide they had expected had finally begun.

As Johnston watched the volcano, the blast cloud quickly obscured the ongoing avalanche. The front of the cloud was magnificent. It was like an immense oncoming waterfall with great blocks of earth and ice cascading from far overhead. The base of the blast cloud reached the ridge on which he was standing and started up the side. Johnston could have tried to take shelter. He might have run inside the trailer, thinking he could survive. But by the time the blast reached the ridge, he must have known he wouldn’t live. It is certainly possible that he stood and watched the oncoming holocaust.

When the blast front hit Coldwater II, it flung the trailer, the Ford Pinto, and Johnston across the top of the ridge as easily as someone would brush away a fly. Johnston undoubtedly lost consciousness and died almost immediately. Everything that was on the top of the ridge flew into the adjacent valley.

Johnston had been right when he was talking with Carolyn Driedger the previous evening. When the debris avalanche generated by the landslide reached the thousand-foot ridge on which Johnston had been standing—a few seconds after the ridgetop was raked clean by the blast cloud—the flowing debris swept up and over the ridge and into the valley beyond. Johnston, his car, and the trailer were buried and have never been found.

On the wall of his childhood bedroom in his parents’ house in Illinois, Johnston had tacked a quotation from Teddy Roosevelt that he had carefully copied as a teenager. It read:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

NOT EVERYONE KILLED NEAR MOUNT ST. HELENS HAD CAMPED there the previous night. Jim Pluard—the foreman of the tree cutters who had objected back in April about logging so close to the mountain—liked to check on his crew’s logging equipment over the weekend. Weyerhaeuser had a lot of money invested in its equipment, and Pluard wanted to make sure it hadn’t been vandalized and would be ready to go Monday morning. He owed a lot to Weyerhaeuser. His father had been a logger, and now two of his sons were in the business. Weyerhaeuser paid a good wage and treated its employees well. The least he could do was keep an eye on things over the weekend.

Sunday morning, Pluard and his wife Kathleen tacked a note to the front door of their home in Toledo. It read: 7:30. GONE TO THE MOUNTAIN. BACK IN TWO HOURS. They got in Pluard’s company pickup and headed up the Spirit Lake Highway. If they left Toledo at seven thirty, they would have gotten to the logging site on the back of the ridge where Johnston was stationed about an hour later.

Like Johnston and the trailer, the Pluards and their pickup were never seen again. Dorothy Stoffel later said that she saw a red pickup driving toward Timberline right before the volcano erupted. But the company pickup Pluard was driving was yellow. Perhaps the color looked different from a height. Otherwise, the occupants of the red pickup remain a mystery.

ON THE RIDGELINE BEHIND JOHNSTON, HAM RADIO OPERATOR GERRY Martin also had been up for hours. Three cats traveled with him in his motorhome, and he walked them on leashes so they wouldn’t run away. He likely had already taken them out that morning. By 8:30 he was in the driver’s seat of his motorhome monitoring the mountain.

At 8:32, he radioed to the network, “Oh oh, I just felt an earthquake, a good one, shaking, uh, here’s a—” At this point his transmission was cut off by a device that limits the length of transmissions.

Another ham radio operator cut in to tell Martin that he should change his frequency for better reception.

Twenty seconds later, Martin resumed his broadcast: “Now we’ve got an eruption down here. Now we got a big slide coming off. The slide is coming off the west slope. Now we’ve got a whole great big eruption out of the crater. And we got another opening up on the west side. The whole west side, northwest side, is sliding down.”

A few seconds later Martin continued: “The whole northwest section and north section blown up, trying to come up over the ridge towards me. I’m gonna back outta here.” He spoke calmly, reflecting his years of navy training.

Martin was turning the key in the ignition, yet he remained on the radio. His words were interrupted by static from the lightning in the blast cloud. He watched the cloud envelop the trailer at Coldwater II. “Gentlemen, the camper and car that’s sitting over to the south of me is covered. It’s going to hit me too.” At this point, the blast was traveling near its maximum speed, which meant that it took about twenty seconds to travel the two miles from Johnston to Martin.

Again, Martin’s microphone switch opened and closed, but he said no more.

LIKE JOHNSTON AND MARTIN, PHOTOGRAPHER REID BLACKBURN arose with the sun that Sunday morning. He took photographs with the two cameras at 7:11, jotting in his notebook the number of shots taken and the time. Blackburn had always been a careful worker, and documentation was essential in his line of work.

The next line in his notebook is marked with the time 8:33. Blackburn was taking photographs of the ongoing eruption. He wrote quickly; his handwriting was shaky. He snapped his notebook shut, threw it in a container with his ham radio, and lowered and latched the container’s lid. Then he jumped in the front seat of his car.

The blast cloud reached him before he could put the key in the ignition. The car windows facing the volcano blew out. The Volvo quickly filled with burning hot ash. Blackburn tried to breathe, but the blast cloud contained little oxygen. His nose, mouth, and lungs filled with ash. Ash from Mount St. Helens tastes like chalk dust mixed with metal; it smells like a dry field stirred by the wind on a hot day. Those must have been among Blackburn’s last sensations as he died.

BECAUSE THE BLAST CLOUD CONSISTED LARGELY OF CRUSHED PUMice and pulverized lava, it was initially much heavier than the surrounding air. As a result, it moved more like a fluid than a gas. It hugged the ground as it flowed away from the volcano. When it encountered a ridge, it swept up one side and down the other. Climbers on Mount Rainier fifty miles to the north said that the blast looked like a dark wave flowing over the countryside.

When the volcano exploded Sunday morning, John Killian was almost certainly on Fawn Lake fishing. Before leaving Vader the previous day, he had thrown a rubber raft into the back of his pickup, and scraps of the raft were later found far down the valley below the lake. Christy was at the campsite with their pet poodle.

From where Christy sat at the outlet of Fawn Lake—nine miles away from the summit of Mount St. Helens—the blast cloud rose above the ridge across the lake like an immense oncoming storm. Then it spilled over the edge of the hill and swept across the water. Instantly, every tree around the lake snapped. Christy was caught in a maelstrom of wood, stone, water, and hot ash. She was torn to pieces. When her left arm was found several months later, it was identified by the wedding band on her finger.

John’s experience was different. Sitting on the edge of the raft, he would have noticed the surface of the water ripple as the air pressure suddenly changed. Then the oncoming blast picked up the raft on which he was sitting as easily as if it was a leaf on a pond. For the last instant of his life, John Killian was flying, flying through the liquid air.

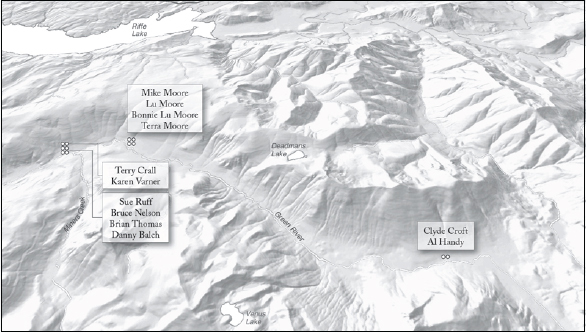

AT 8:30 ON SUNDAY MORNING, CLYDE CROFT AND AL HANDY, WHO had camped near the Polar Star Mine, were preparing their horses for the journey back to Ryan Lake. It was a quiet morning, broken only by the murmuring of the nearby Green River. Suddenly the air pressure began to change, making their ears pop. When they looked to the south, they saw a great black wall of ash rising above the ridgeline. Then the wall of ash crested the ridge and began to descend toward their campground.

The Green River valley marked the northern edge of the blast zone. By the time it reached the Green River, the blast cloud had deposited so much coarse ash over the countryside, and it had expanded so greatly because of the heat it contained, that it became less dense than the surrounding air. It began to rise, like smoke from a fire. A countervailing wind sprang up from the north, pushing the blast cloud higher. The wall of ash moved laterally back and forth across the Green River, first in one direction and then the other. Some parts of the Green River valley were engulfed. Others were virtually untouched.

Croft and Handy had camped in a part of the valley that was engulfed. Handy raced up the hillside north of the river, hoping to take cover in the mine. He was about twenty yards away from the entrance when the ash enveloped him. The hot ash filled his throat and seared his lungs. Within seconds, Handy and the two horses died of ash asphyxiation.

Croft made a different decision. He grabbed a sleeping bag and dove into the Green River. Above him, hot ash fell onto the sleeping bag. Below him, the frigid water of the Green River swirled around him. For more than an hour he remained partially submerged in the water with the sleeping bag over his head. It was completely dark. There was nothing to do but wait.

Finally the darkness lifted enough for him to rise from the river. He began walking up the trail to Ryan Lake, holding the sleeping bag over his head. Croft had been a combat veteran of the Vietnam War and had survived a hard childhood on a poor Texas farm. He was strong and determined. Burns covered his face, arms, and chest, but he kept going. Nothing was more important than continuing to move.

His breath became labored as he inhaled more and more ash. Finally he reached the truck at Ryan Lake. It was covered by fallen trees, unusable. He pulled out a case of warm Olympia from the front seat and quickly downed two cans of beer. But it hurt to swallow. The hot ash had burned his throat and lungs.

Croft set off again on the road toward Randle, twenty-five miles to the north. He didn’t have to get all the way there. Someone would rescue him if he could get away from the ash. Two miles north of Ryan Lake, he began to grow dizzy. He weaved from side to side as he walked. He came upon a large uprooted tree. He tried to climb over the tree, but it was too large and he was too weak. He dropped to his knees and began digging through the hot ash, forming a tunnel so he could crawl underneath. He made it to the other side, got back on his feet, and kept walking.

Finally he made it past the blown-down trees. Tractors and other machinery were parked on the side of the road. Croft got into one, and turned the key in the ignition, but the tractor would not start. Because of the heavy ashfall, all of the vehicles were unusable. He gave up and continued down the road.

For three more miles he walked. If he kept going, he would make it. But he had to rest. He had walked eight miles, badly burned, with his lungs half full of ash. He moved to the side of the road, laid his sleeping bag in the ditch, and wriggled inside. He rested his head on his arm. Slowly his breathing quieted, and then stopped.

The people camping in the Green River valley Sunday morning

TERRY CRALL, KAREN VARNER, BRUCE NELSON, SUE RUFF, BRIAN THOMAS, AND DANNY BALCH

ON SUNDAY MORNING, TERRY CRALL LEFT HIS GIRLFRIEND, KAREN Varner, in their tent and went fishing for steelhead in the nearby Green River. In the tent with Karen was Tye, an Australian shepherd, and Tye’s three puppies. Nearby, Bruce Nelson and Sue Ruff huddled around the fire trying to get warm. The Green River is nestled so deeply amid the ridges north of Mount St. Helens that it takes the sun a long time to reach the valley floor. They had stuck some leftover marshmallows on sticks and were waiting for a pot of water to boil to make coffee. About 70 yards down the trail toward Road 2500, Brian Thomas and Danny Balch were still sleeping in a tent after staying up late drinking beer around the campfire.

About eight thirty, Terry came bursting into the campsite to tell Sue and Bruce about a huge fish that had broke his line. As Sue rose to get a pack of Camel Lights from the tent, she noticed a small plume of smoke rising above the southwestern tree line. “There must be a fire somewhere,” she said. She considered taking a picture of the strange plume of smoke, but as she stared at it, it began to change.

Quickly the plume filled the sky to the south and west, with odd-looking stalks extending upward and outward. Suddenly a gust of cold air blew through the campsite. Their campfire shot sideways, and Sue’s braids blew straight out from her head. The cloud above them quickly turned from yellow to red to black. Within seconds, hurricane-force winds were blowing through the trees.

Terry ran to the tent where Karen and the dogs were sleeping and jumped inside. An instant later, a large tree fell directly on top of them.

Bruce wrapped his arms around Sue. They were standing between two large Douglas fir trees. All around them, trees were falling, creating great booming sounds like cannons being fired. The tree standing next to them fell, and the couple toppled into the hole where the roots had been. Above them, falling trees partly covered the hole. They were engulfed by darkness. They clutched each other as the air became warm and then burning hot, as though they were in a giant furnace. Bruce, who’d been a baker, estimated that the temperature reached more than 500 degrees Fahrenheit. All the hair on their arms was burned off, and they could feel the hair on their heads being singed.

“Are you okay?” Bruce whispered.

“Okay,” Sue replied. Bruce could barely hear her, even though her face was inches from his own.

“My God, Sue,” he said. “We’re dead.” Chalky grit filled his mouth.

“Bullshit,” she replied, “we’re not dead yet.”

Nearby, Brian and Danny had both leapt out of their tent when Brian, sensing that something was wrong, had looked out the back of the tent and had seen the blast cloud approaching. Instantly the cloud was upon them. The trees around the campground all fell at once, as if yanked from the ground by an invisible hand. Brian rolled behind a log that had already fallen. In seconds he was buried by ash, branches, and debris. The blast pushed Danny to the ground. He was pelted by mud and ice, which melted as it hit him. Then he was hit by a wave of scorching heat. He flung out blindly, trying to find anything to grab on to. His hands grasped some burning logs, and he screamed in pain as the skin on his hands melted. Another terrible burn covered his left leg. He called for Brian but got no response. Thick clumps of dirt began to fall in the pitch-black darkness.

In the root pit farther up the trail, scalding ash was falling on Sue and Bruce. They had to dig the chalky gray grit from their mouths with their fingers. They pulled their shirts over their heads to protect themselves from inhaling too much ash. They felt themselves getting cold, sleepy, and nauseous, though whether because of gases in the blast cloud or shock they couldn’t tell.

Fifteen minutes after the blast hit, the cloud shifted to the south and the sky lightened. Still, chunks of coarse particles, ice, and vegetation kept falling from above and hitting the fallen trees. Slowly, Bruce and Sue began to dig their way out of the root pit, gagging on the ash-filled air. They called out to their friends but heard no reply. Sue managed to take out her ash-coated contact lenses.

For an hour and a half they huddled behind a fallen tree. Visibility was low. The air smelled of brimstone, like a hot spring. There were no signs of life. “If we get out of here alive, you’re going to marry me,” Bruce said. Sue said that she would.

When the ash cloud had lightened, Danny had made his way to the river to soothe his burned hands and leg. Then he set out to search for Brian. He was struggling through a tangle of trees when he felt something grab his leg. It was Brian. He had been badly injured by a falling tree. Danny managed to pull him from under the tree as the ash continued to fall. Brian was screaming with pain. They sat on a pile of debris, their shirts over their faces, as the ash pelted their backs, first hard and then softer, and then harder again. Sometimes they could hardly see their hands in front of their faces, while at other times the air cleared. The previous night they had camped in a dense old-growth forest. Now they were in a clearing piled high with downed trees. All of the trees were covered in a thick layer of hot gray ash. Brian still had on the long johns that he had worn to bed. Danny had not had time to put on his shoes when he jumped out of the tent, and his feet were now burned nearly as badly as his hands.

They heard Bruce and Sue calling for them, and Danny shouted out a response. Out of the gray fog, Bruce and Sue appeared. Sue looked at Danny. His skin hung from his hands like a burnt marshmallow, and his fingers were fused together. They tried to get Brian to stand, but his hip was broken and he could not walk. For the next hour, they struggled to get Brian to the dilapidated shack on the Green River trail near their campground. It was a short distance away, but they had to lift and roll their friend over dozens of downed trees. They reached the cabin and started discussing what to do. “Don’t leave me here to die!” Brian pleaded with them. But the three friends agreed that their odds would be better if they stayed together. Only the front of the shack was intact, so they built a lean-to of logs to cover Brian if more hot ash fell. They assured him that they would return with help.

Bruce, Sue, and Danny made their way across fallen trees to the bridge over the Green River. Danny’s and Bruce’s pickups were okay, but so many trees had fallen that the pickups could not be driven. The three friends began trudging down Road 2500. This had been second-growth forest, so the trees they had to climb over were smaller. But the ash was burning hot, and Danny had only socks on. They hiked for an hour and a half but made only two miles. Danny was slowing them down. Bruce said that they had to go faster, even if Danny couldn’t keep up.

“Can’t you stay with me?” Danny begged.

“No,” Bruce replied. “We must reach help. Brian’ll die. . . . If something happens, get in the water.” They left Danny sitting by the river.

Bruce and Sue continued down Road 2500. They wondered if there was anything left of their homes or if the volcano had destroyed all of southwestern Washington. At one point they passed several dozen elk, whose nostrils were plugged with ash. They patted the animals and moved on. Birds lay dead or immobilized in the ash. Sue picked one up and washed it in a puddle, but when she set it in a bush it fell over gasping. I can’t save even one little bird, she thought.

Several miles later they came across Grant Christensen, age fifty-nine, who was walking on Road 2500 after driving into the devastation zone earlier that day to try to recover some of his brother’s tools from Weyerhaeuser’s Camp Baker. Together they began hiking toward safety. Christiansen told them that he’d been a survivor of Guadalcanal in 1942 and had spent two days in a lifeboat before he was rescued. He had a glass eye that he popped out and cleaned whenever it became too ashy.

They were about to stop for the night when they heard a helicopter. They shouted and stomped on the ground, raising a cloud of dust. The helicopter crew saw them and landed nearby. Sue and Bruce had hiked fifteen miles since the volcano erupted.

They told the crew about Brian and Danny. “No one could be alive that far up,” said a crewmember.

“We came that far,” said Bruce. The crew agreed to search, though darkness was approaching. They flew up the river, but the bridge over the Green River was too small for the Huey to land, and every other potential landing site was covered with logs. They radioed a smaller helicopter nearby, which managed to land on the bridge with its tail hanging over the edge.

But Brian was no longer at the shack. After waiting for an hour, he had grown convinced that he would die if he stayed there. He began to crawl toward Road 2500, trying to keep the weight off his shattered hip. At each downed tree, he crawled underneath if he could. Otherwise he dragged himself up the tree and flopped down the other side. By the time the crew found him that evening and flew him to a hospital in Longview, he had made it only two hundred yards from his starting point.

Farther down the Green River, Danny also had decided that he would die if he did not keep moving. He pushed himself onto his burned feet. Sometimes he walked in the river, where the water made the pain less agonizing. Other times he took the ash-filled road.

Suddenly he heard a voice. “Hey, survivor.” It was logger Buzz Smith and his two sons. When the volcano had erupted, they had heard a crack, crack, crack, like someone shooting a rifle. Gusts of wind blew through the trees in which they were camping. A black cloud appeared in the sky overhead, and hard objects the size of marbles began falling through the trees. Then it went completely black. They huddled under a sleeping bag and a fallen tree while rocks, mud, and ash fell in the darkness. One boy asked, “Daddy, are we going to live with Jesus?”

“Well, maybe,” Smith replied, “but not now.”

When it lightened, they began walking down Miners Creek, and then down the Green River. The river was too muddy to drink from, and the boys quickly grew thirsty and tired. Smith told them to think of their trek “like a Hardy Boys story, that we’re going to make a very difficult journey in very small steps.” As they walked down Road 2500, they saw tracks where birds and insects had walked through the ash. “Look,” Smith said, “even birds and hornets are walking. That’s how we’ll get out.”

When they met Danny, Smith put some tennis shoes from his pack on Danny’s feet and gave him a fruit roll. The four of them continued walking. Over the next three hours, they walked three more miles to where Road 2500 again crosses the Green River. Smith found a seep of fresh water in the riverbank, and all four of them drank deeply. As Danny drank, Smith was amazed to see water oozing from his neck. “No skin,” he later recalled. “He’d been so caked in ash I hadn’t noticed this. Now I saw how bad off he was and realized I should have paid more attention.”

“You’re hurt,” he told Danny. “You need to drink more water.”

A hundred yards past the bridge, at about seven thirty in the evening, a National Guard Huey flew over them. It landed farther down the road, and crewmen carried Smith’s sons to the helicopter while the two men trudged the rest of the way. Danny had walked nearly nine miles on his severely burned feet before the helicopter took off to deliver him to the Longview hospital.

MIKE, LU, BONNIE LU, AND TERRA MOORE

SUNDAY MORNING, LU MOORE WAS PREPARING BREAKFAST FOR HER two daughters and husband as Mike wandered around the campsite taking pictures with his camera. Suddenly she felt as if a giant hand were squeezing her body. Her ears popped, so that she had to swallow to equalize the pressure. Mike was a geology graduate and immediately wondered if it was an eruption. But how could they be feeling the effects way out here on the Green River?

Then Lu noticed a cloud rising above the ridge to the south, and it rapidly grew larger. Mike ran to a nearby clearing, realizing that an eruption was going on and thinking that he could get some photographs of it. But as soon as he got out of the trees, he understood that this was an eruption unlike any that had ever occurred before. The cloud towered above him, its blackness transformed into an immense wall of grays and yellows. The face of the wall was churning, as if driven by an eggbeater. It was one of the most beautiful things he had ever seen, Mike thought.

By the time the blast reached the Green River, it was no longer flowing over every obstacle it encountered. Instead, it was following the contours of the land, like a wave sweeping around rocks. Here the trees knocked down by the blast did not necessarily point away from the volcano. They formed fantastic swirling patterns, with some trees pointing straight back at the source of the blast.

Just south of the Moores’ campground is a high point of land known as Black Mountain. The blast swept around either side of the mountain, engulfing the party from Kelso and Longview on one side and Croft and Handy on the other. But because the Miners Creek campsite was already taken by Sue Ruff and her friends, the Moores had camped in the shadow cast by Black Mountain. None of the old-growth trees in which they were camping fell.

As Mike continued to take pictures, Lu quickly took down the tent and threw things into their backpacks. The thunder from the nearby cloud was so loud that they had to shout to each other. The cloud came closer. They decided that their best bet was to take shelter in a dilapidated elk hunter’s shack nearby. Within just a few minutes they managed to get all of their gear and the two girls into the shack. Then the ash began to fall. At first it sounded like massive raindrops hitting the roof of the shack. But when Mike stuck his hand outside the door, warm ash and small mud balls bounced off his palm. The valley outside the shack got darker and darker until, suddenly, all of the light was gone. The thunder was so loud, coming every five to ten seconds, that it was impossible for them to hear one another, but they never saw a flash of lightning, so thick was the ash.

For more than an hour, the shack was engulfed by darkness. They covered the baby with blankets and plastic tarps and breathed through dampened socks to keep ash out of their lungs. Bonnie Lu was scared, but Mike and Lu explained what was happening, and she calmed down. The ash was devil’s snow, she decided, which made her feel better.

When it became light again and the ash stopped falling so heavily, Mike pushed open the door of the shack and stepped outside. Everything was covered by several inches of gray, powdery material. It was getting lighter to the west. They would be okay, he thought. Lu nursed the baby.

They decided to begin walking the two and a half miles back to their car. Lu strapped the baby into her backpack, wrapping her bald head in a thermal blanket. Bonnie Lu walked alongside in a state of excitement and shock.

After covering about a mile, they began to encounter trees that had fallen across the trail. These blowdowns weren’t here the previous day. Why were they here now? they wondered. They veered off the trail to try to get around the newly downed trees. With every step, ash billowed from the ground and nearby vegetation, partially blinding Mike. Lu had to wash out his eyes for fifteen minutes with water from their water bottles before they could continue.

They got past the first few blowdowns. But then they emerged from the trees and beheld an incredible sight. Ahead of them the entire forest had fallen. They thought they might have somehow gotten onto the wrong trail, since they had not encountered anything like this the previous day. But slowly the realization dawned: the volcano had destroyed the mile of old-growth forests between them and their car. They couldn’t get over or around the trees with two children, especially given how tired they were. With only three hours of daylight left, they knew they would have to spend another night in the woods.

Mike and Lu were experienced hikers who always carried extra provisions in case of an emergency. They retreated to the standing trees and set up their tent off the trail so they wouldn’t be trampled by the elk whose footprints they had seen in the ash. They had dinner with the girls and fell asleep.

Remarkably, they all slept soundly until well after the sun had risen Monday morning. By ten in the morning they were back at the blowdown and ready to start making their way to the car. For the first five hundred feet or so they walked along two downed logs parallel to the path. But then the route got much tougher. They had to climb over eight-to-ten-foot logs piled in haphazard, ash-covered piles. Mike calculated that it would take at least nine hours for them to reach the car.

Shortly before noon, they heard the sounds of a helicopter. Lu was wearing a bright-orange coat, and the helicopter crew had picked out the color against the gray of the ash. The helicopter couldn’t land amid the fallen trees, but it lowered a paramedic to the ground. He and the Moores decided to move closer to the river to see if the helicopter could find a place to set down. It took them an hour to cover two hundred yards, but they were able to make their way to an island in the middle of the river.

A small Army Reserve helicopter managed to lower one skid to a gravel bar while hovering above the ash-covered ground. The Moores began to climb in while ash poured through the open door. The pilot was afraid the helicopter would be overloaded. “Leave that damn thing,” he shouted, nodding toward Lu’s backpack. “We’re grossed on weight!” A crewman who had given up his seat so the Moores could be rescued began pulling the pack back out the door.

Lu fought the crewman to keep the pack. “There’s a baby in it!” she screamed.

“Okay,” said the pilot, “keep the baby.”

Three months later, Mike and Lu came back to the Green River. Partly they wanted to look for Mike’s $800 Zeiss binoculars, which they found in the ash just where Mike had dropped them. Then they stood and beheld the old-growth forest in which they had camped. As Lu later recalled, it was as if the forest were saying to them, “You’ve been saved. Now do something about it.”