EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

One thinks of Robert Creeley, foremost and primarily, as a writer. That being the case, it must be said a large part of that writing, even the largest part—the volume of it—was correspondence. Simply the list of names of correspondents, available at the Stanford Special Collections website, runs to well over one hundred pages; there are in addition substantial collections of his correspondence at Washington University (St. Louis), the University of Connecticut at Storrs, as well as numerous other archives and private collections around the world. We have sifted through this correspondence with three aims in mind: (1) as he requested of us, “to tell a story,” that is, what he did; (2) to track his thinking, his poetics, philosophy, and politics, across the six decades this selection represents—in other words, what he thought; and (3) to tell the larger story, through the prism of his engagements, of the individuals and societies he encountered. This last, of course, is necessarily the most contingent aspect of the project, yet it seems fair to say this volume represents not simply a history of Robert Creeley but also a version of recent history, literary and otherwise, of and within the post–Second World War world.

We begin this selection the same year as the first volume of Creeley’s Collected Poems, 1945, which finds him on his way to Burma to serve as an ambulance driver. There follow a few lengthy letters to fellow writer and editorial collaborator Jacob Leed; these reflect the humble situation of the young New Hampshire chicken farmer with the voracious intellect that would shortly engage Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and inaugurate an intense dialogue with Charles Olson that would quickly and irreversibly change, quite literally, the concept of poetry for our time. With his friend Leed, Creeley had hatched a scheme to start a literary magazine to be called the Lititz Review (after the small town in Pennsylvania where they planned to print it). In contacting Pound, Williams, and others, Creeley was soliciting both writing and advice from the previous generation.

Creeley was twenty-four when he began writing to William Carlos Williams, then sixty-seven, initiating his connection with a poet who was and remained for him a guiding poetic sensibility. The Williams correspondence proves remarkable, not only for its invaluable contribution to the poetics of our time, but also as autobiographical document. Creeley wrote regularly, but by no means weekly or even monthly, to Williams (as he often did with other correspondents, particularly Charles Olson). As a result the letters are often a summation of recent developments—writings, moves, romances, literary politics. It was through Williams that Creeley came into contact with Charles Olson.

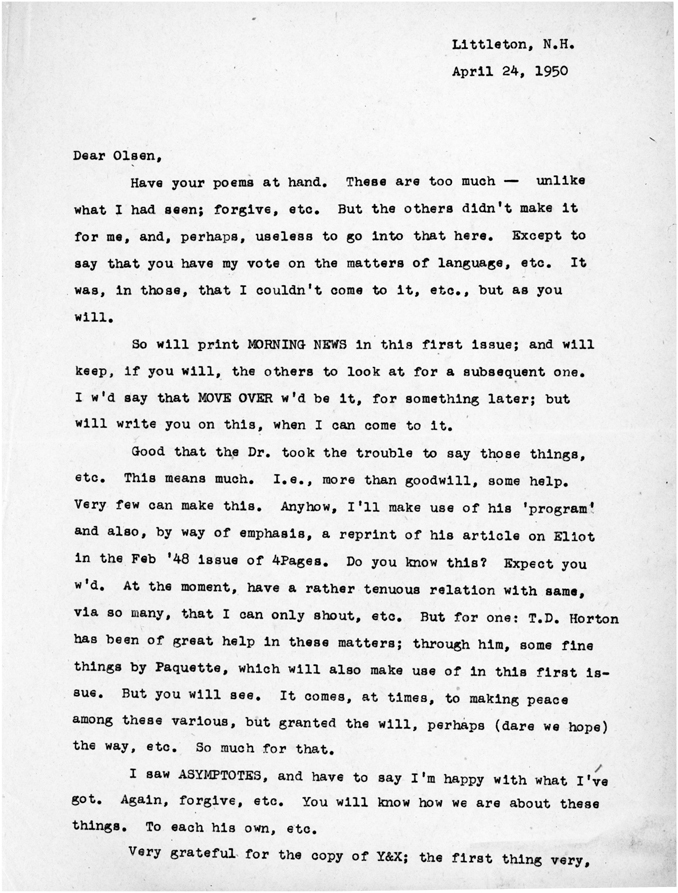

The celebrated Olson-Creeley correspondence, edited primarily by George Butterick and published by Black Sparrow Press in ten volumes between 1980 and 1996, covers only the period of their letters between April 1950 and July 1952. As Butterick notes in his introduction to the first volume, “There are roughly one thousand surviving pieces of correspondence in all, with Creeley outwriting Olson at a rate of three to one.” The approximately three thousand pages of Creeley’s letters to Olson housed at the Olson archive at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, make up about a fifth of the fifteen thousand or so typed or handwritten letters, cards, and faxes we have collected or reviewed, along with a practically uncountable number of e-mails. Creeley early on recognized the potential literary value of the exchange with Olson, publishing as The Mayan Letters a selection of Olson’s letters from the Yucatán (1951–52) on his own Divers Press in Majorca in 1954 and reprinting them in his edition of Olson’s Selected Writings for New Directions in 1966. The letters by Creeley to Olson after 1952 appear here in print for the first time and only hint at the dimensions of Butterick’s unfinished project to print all of the letters by the two poets to each other. Lasting and influential connections also made in the early fifties are documented in the correspondences with Cid Corman, Larry Eigner, and Denise Levertov. With each of these poets Creeley played by turns mentor, mentee, publisher, and friend.

From Littleton, New Hampshire, Creeley moved his young family in 1951 to the south of France, first to Fontrousse and then Lambesc, both in the environs of Aix-en-Provence. Mitchell Goodman and Denise Levertov had convinced Creeley that the cheaper cost of living in postwar France would allow them to live on his wife’s small trust fund (about two hundred dollars a month), thus freeing him to devote time to writing. In the decade of the fifties alone, Creeley lived in New Hampshire, in the south of France, on the island of Majorca, at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, briefly in both New York City and the San Francisco Bay area, then on to New Mexico, and finally, ending the decade in Guatemala. Having deliberately sought isolation in remote, inexpensive living situations, Creeley compensated for his lack of face-to-face contact with his peers through his prolific letter writing. The fifties alone account for about 40 percent of the present volume.

Page one of Creeley’s first letter to Charles Olson, April 24, 1950. Courtesy of the Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries.

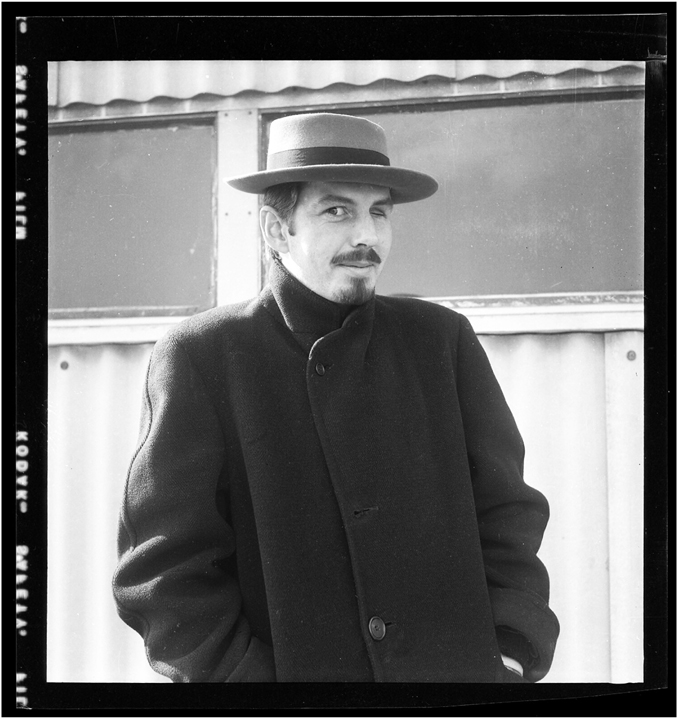

Robert Creeley, Black Mountain, North Carolina, 1955. Photograph by Jonathan Williams.

Creeley’s spirited rejection of the dominant poetry climate was spurred by letters from Pound and Williams, and although his esteem for Pound the poet and editor remained, Creeley recognized fairly quickly that his advice was seriously hampered by both his monomania (to use a relatively neutral term) and his sycophantic, not to mention racist, retinue. Williams, however, proved an invaluable collaborator in the push toward new forms, and their correspondence never diminished despite Williams’s failing health in his later years.

The Lititz Review, perhaps predictably, never materialized; however, Creeley exercised considerable influence on the editorial direction of Cid Corman’s journal Origin, the first issue of which prominently featured Charles Olson. Creeley began his own Divers Press in 1953. The following is from a handbill advertising the Divers debut, featuring new titles by Paul Blackburn, Olson, Eigner, and Creeley:

Printing is cheap in Mallorca, and for a small press like our own it means freedom from commercial pressures. It means, too, that we can design our books in a way that we want, since they are handset and made with an almost forgotten sense of craft. Above all, it is our own chance to print what we actually like and believe in.

Creeley also, at Olson’s behest, served as editor of the Black Mountain Review, the first number appearing in the spring of 1954 and running through seven issues, to the fall of 1957. This editorship proved one of the crucial contexts for a generation of writers associated not only with Black Mountain but also for Beat and New York School poetries. It also plunged him into some bruising literary feuds, notably with Kenneth Rexroth and even for a brief time with Robert Duncan. His friendship with Duncan recovered and flourished; his association with Rexroth did not. Meanwhile, his brief time spent at Black Mountain College (spring 1954 and autumn 1955) allowed him to form lasting relationships not just with Olson but also with Ed Dorn, Fielding Dawson, and others, and gave rise to the name of the “movement” or “school” with which he is most often associated.

If Creeley’s letters from this time are deeply inflected by the literary politics of the period, they are even more concerned with how an alternative poetics might be constituted. A letter might include a vignette of seeing Picasso in a café in Aix or a long description of a trip to Spain, or a car crash at Black Mountain, before delving extensively into his own practice of poetry, or offering in-depth critiques of poems by his friends, or overviews of exciting tendencies among the San Francisco group. Some of this poetic theory shares Williams’s concerns with the American idiom. Some of it relates to Creeley’s shared passion with Olson for their differing articulations of a Projective Verse poetics, though this is but one aspect of the prodigious range of their discourse. He strongly differs with Williams on the question of measure: “We don’t need a ‘measure’ so much as we do need, desperately, some sense of our materials, the elements if you will from which the poem forms” (January 26, 1955). The jazz idiom of Bop, and Charlie Parker in particular, is an important source for this approach. This to Olson, April 8, 1953:

I am more influenced by Charley Parker, in my acts, than by any other man, living or dead. IF you will listen to five records, say, you will see how the whole biz ties in—i.e., how, say, the whole sense of a loop, for a story, came in, and how, too, these senses of rhythm in a poem (or a story too, for that matter) got in. Well, I am not at all joking, etc. Bird makes Ez look like a school-boy, in point of rhythms. And his sense, of how one rhythm can activate the premise for, another. Viz, how a can lead to b, in all that multiplicity of the possible. It is a fact, for one thing, that Bird, in his early records, damn rarely ever comes in on the so-called beat. And, as well, that what point he does come in on, is not at all ‘gratuitous’, but is, in fact, involved in a figure of rhythm which is as dominant in what it leaves out, as what it leaves in.

Creeley headed to New York from Black Mountain in late 1955 to see to the details of his divorce from Ann MacKinnon. There he also spent time with Williams and Louis Zukofsky and became for a brief time a regular at the famous Cedar Bar, fraternizing with the likes of Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock, among others. He was then on to San Francisco in early 1956, where his association with Ginsberg and Kerouac began. After a few months marked by an intense, ultimately unhappy affair with Marthe Rexroth, Creeley landed in Albuquerque, New Mexico, securing a job as a French teacher at a boys’ high school. After a spell he met and soon married Bobbie Louise Hawkins (then Bobbie Hall), with whom he had two daughters, Sarah and Katherine.

The Creeleys moved, in the fall of 1959, to Guatemala. He had secured a job tutoring the children of the owner of a finca. The hope had been to have time to write and also to live cheaply and save up some money. Clearly, only the former transpired. Creeley grouses regularly about the cost of living in Guatemala in his formidably prolific correspondence of this period and is deeply critical of his employers and the economic injustice of the Guatemalan situation generally, not just his own. Nevertheless it is in this period that he begins to see a way to “make it,” as he often said. This was largely a result of the reception of his ninth book, A Form of Women (1959), of his inclusion in Donald Allen’s high-profile anthology The New American Poetry (1960), and of the news, received while in Guatemala, that Scribner’s had accepted his early collected poems for publication as For Love (1962). After living a somewhat marginalized, slightly vagabond existence through the fifties, Robert Creeley, in the sixties, would soon become one of the most celebrated poets of his time.

Though his affiliation with the University of British Columbia in Vancouver was relatively brief (one academic year, 1962–63), it did allow him, with the help of Warren Tallman, to stage the famous Vancouver Poetry Conference in the summer of 1963. As letters to key figures reveal, Creeley clearly felt the large part of the “work” of the conference would get done not at the official events but in relatively private settings with good friends. By the time he began his first real, long-term teaching position at the University of Buffalo in 1966, Creeley was the poetic equivalent of a rock star, his letters increasingly devoted to the schedules of cross-country and international reading trips and the consequent demands on his time. His poetry also was changing. In this period he writes to Olson, and others, that the poems in For Love already seem to have been written by a different person. In the books Words (1967) and Pieces (1968), he breaks out of the model of the single poem as crafted artifact toward a serial practice influenced in part by the works of Zukofsky—a move that became crucially important to a younger group of writers that would come to be known as the Language poets. These changes in Creeley’s verse were not a break with his practice of the fifties. An unpublished poem sent to Olson (May 28, 1956) can be seen as of a piece with For Love as well as a clear foreshadowing of the work of the sixties and seventies:

HOW ABOUT THAT

It must be horrible

when you are dead

to know you planned just a little

too far ahead.

While Creeley’s success as a poet was increasingly secured by the late sixties, his personal life became more chaotic during the extended period of his breakup and eventual divorce from his second wife, Bobbie Louise Hawkins. His letters to her in Bolinas, where they had acquired a house in 1970, are often troubled and conflicted but also loving and filled with the quotidian concerns of a long-term intimacy. Adding to the emotion of the time were the untimely deaths of two of his dearest friends and collaborators: Charles Olson in 1970, at age sixty, and Paul Blackburn in 1971, at age forty-four. This period of personal dislocation eventually resolved with Creeley’s marriage in 1976 to his third wife, Penelope Highton, and the births of their two children, Will and Hannah, in the early eighties. Creeley had met Penelope on an epic reading tour of the Pacific Basin, which became the primary subject of his first book for New Directions, Hello: A Journal, February 29—May 3, 1976. One aspect of Creeley’s personal life that becomes apparent when viewing the overall body of letters is that for almost his entire adult life, his home life, often with small children, dominated his concerns.

Although he had taught in various contexts since the mid-fifties, Creeley only settled into full-time teaching in Buffalo in 1973. Clearly, he was a one-of-a-kind professor, as this from Peter Middleton’s account of studying with him, “Scenes of Instruction: Creeley’s Reflexive Poetics,” demonstrates:

Robert Creeley was usually the last to arrive for the seminar. He liked to stand sideways in the door for a few moments, his good eye looking us over and his blind eye safely out in the corridor, his army surplus hat still on as if he might decide not to enter once he had assessed his classroom, whatever the timetable said, because this was to be an act of choice. What mattered was the quality of the encounter and there would always be part of him that would be reflecting with an inner eye on its implications. He came in, put down his shoulder bag on the desk, placed his hat ritually on the table in front of him, began to talk as he sat down, and then talked on solidly for the entire class, only occasionally interpolating a question or appeal for responses, rarely waiting for a rejoinder. (Form, Power, and Person in Robert Creeley’s Life and Work, ed. Fredman and McCaffery, University of Iowa Press, 2010, 159)

Starting earlier, but particularly in the seventies, Creeley, in addition to teaching, increasingly authored essays, engaged in interviews, and collaborated with visual artists; thus, although his correspondence does not reveal a lack of concern with poetics, his venues for that conversation multiplied radically compared with those of the fifties. A multigenerational poet, he sought to keep up with the formal and compositional developments of avant-garde writing, having up-and-down—sometimes heated—relationships with correspondents whose writing practices he came to view as dated or reactionary. At other times he spoke well of W. S. Merwin, whom he had once dismissed, and had friendships with relatively conservative poets such as Robert Bly and James Dickey.

Creeley was an early adopter of fax machines, word processing, and e-mail, and his epistolary habits evolved with each new technology. What this record shows is that in the last decade or more of his life, Creeley was as generous to a newer generation of poets as he had been solicitous of his precursors when he was getting his start. Simply for reasons of space, much of this book might be thought of as representative of, rather than encompassing, Creeley’s letter-writing practice. We have represented, as far as possible, the kinds of letters he wrote; to “tell the story,” but also to provide as useful a document as possible. The letters compiled here are “representative” not only of Creeley but also of what it was like to be a poet in his time, albeit an unusually successful one. Letters reflecting the work of poetics with friends, critics, and editors; family concerns; communications with students; dealings with his many publishers; the responsibilities of coordinating reading series; institutional politics—all have been offered here as examples of which there are many more. Our only wish is that we could have been even more inclusive.

This is not the first volume dedicated to Creeley’s correspondence. The ambitious Olson-Creeley correspondence published by Black Sparrow has already been mentioned, but we would do well also to mention two other, quite different publications: one with an important contemporary, Irving Layton and Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence, 1953–1978, edited by Ekbert Faas and Sabrina Reed (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), and the other, Day Book of a Virtual Poet (Spuyten Duyvil Press, 1999), which collects e-mail correspondence to high school students participating in an online honors poetry course. For an excellent overview of the development of Creeley’s poetry as well as greater biographical detail, we would suggest Benjamin Friedlander’s introduction to Creeley’s Selected Poems, 1945–2005 (University of California Press, 2008), as well as Tom Clark’s Robert Creeley and the Genius of the American Common Place (New Directions, 1993), which includes Creeley’s own ten-thousand-word “Autobiography.” An excellent bibliography as well as a generous selection of Creeley’s writing may be found at the Electronic Poetry Center (http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/creeley/). A wealth of audio and video recordings of his readings, lectures, and interviews are available at PennSound (http://writing.upenn.edu/pennsound/x/Creeley.php).

Robert Creeley (right) and Tom Raworth, Maryland Institute College of Art, 1999. Photograph by Rod Smith.

In 2003, at the age of seventy-six, Creeley left Buffalo for a new teaching position at Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island, an appointment that lasted only a few years. Robert Creeley died at sunrise on March 30, 2005, in Odessa, Texas, of complications from pneumonia. He had been in residency with the Lannan Foundation in Marfa, Texas, for the spring, after a brief teaching stint at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, during the winter. He had given his final reading at the University of Virginia just days before he died.

Robert Creeley, Ligura Study Center, Bogliasco, Italy, 2002. Photograph by Penelope Creeley.

We were fortunate to benefit from Creeley’s advice on the shape of this volume while he was still with us (see, for example, his e-mail to Rod Smith 7/17/03). He definitely wanted letters to family included and saw no reason to impose an artificial distinction between typewritten letters and their electronic equivalent. While all of the individuals and university archives listed in our acknowledgments have helped make this volume possible, it is finally, and of course, Robert Creeley’s extraordinary energy and acumen that give this book its inherent value.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Our editorial policy for the presentation of these letters has all along been to maintain a minimum of editorial interference in the body of the text and to present letters only in their entirety. There are no excerpted letters, also no editorial headnotes to sections, and no editorializing about which letters stand out for whatever reason. We have kept Creeley’s famous dictum that “form is never more than an extension of content” in front of us while making decisions on the presentation of these letters and have allowed this to guide us at the micro- as well as the macrolevel.

Creeley, like Charles Olson, wrote many letters that reflect a projective verse or field poetics in his approach to use of the space on the page. These letters date almost exclusively from the early fifties, though aspects of this style remain visible throughout his life as a correspondent. We have endeavored to reproduce these field poetics letters in their original appearance, including not only nonstandard indentation but also blocked paragraphs separated by space. The spacing of the original letters is presented through the entirety of parts 1 and 2. At the request of the press we’ve allowed unindented paragraphs separated by a space in later letters, parts 3 through 6, to be presented as standard paragraphs. Nonstandard indentations, regardless of date, have been preserved.

With a few exceptions, our notes to individual letters are located at the end of the text, with notes keyed to the correspondent and date of the letter. Within the text itself all of our contributions are in square brackets and in plain type. The bracketed material typically identifies an addition to the text made after the original typescript, for example, “[note in left margin: Creeley addition].” When these additions are handwritten, they are presented in italics. We have employed the caret symbol, “^,” to signal marginal or intertextual insertions indicated by Creeley in the document. When an entire letter was handwritten we have presented it in roman type to avoid large passages in italics. We do present postcards, when handwritten, in italics. Much of Creeley’s marginalia, sometimes typed, sometimes handwritten, is simply the continuation of a letter after signing off, at times signaled by a “P.S.,” just as often not. In many instances additions above the salutation are clearly intended to be the first thing the recipient read. Whether jokes, commentary on writing or music, news of friends or family, and so forth, these have often been presented in their original location in the typescript. Notes above the salutation of lesser import have been presented at the end of the letter, with their position indicated in brackets.

Influenced by Olson and Pound, Creeley’s style as a letter writer included a number of nonnormative usages of punctuation. Slashes, hyphens, em-dashes, commas, periods, colons (including a space preceding them), and open parentheses are variously employed in nonstandard ways as rhythmic devices. We have attempted to preserve all of these characteristics of the original documents. In the interest of conveying the changing technological contexts Creeley as a correspondent negotiated, we have also chosen to include aspects specific to the various technologies he used. These include transcriptions of university or other letterhead, postcard descriptions, exact transcriptions of telegrams, and typical fax and e-mail headers. Occasionally basic information such as subject and e-mail address did not survive in the electronic files. In those instances we present only what has survived.

Creeley was a skilled and fast two-fingered typist. He also clearly proofread his letters once completed and corrected what few typos there might be. Our commitment has been to respect the original text, though on occasion we have silently corrected clearly unintended mistakes. We are appending a short biographical and bibliographical chronology for the reader’s reference.

Rod Smith, Peter Baker, Kaplan Harris

October 2012