WATCH THE SUN RISE ON A CONTINENT

Having arrived late the previous evening in St. John’s, and with just four pitiful hours of sleep, I awake with a fool’s determination to witness the first sunrise in North America. Just twenty-five minutes’ drive away from my hotel is Cape Spear, the most easterly point in Canada and, notwithstanding the technicalities of Greenland, the most easterly point of North America. When you have but one morning in St. John’s, you have to make it count.

Sunrises are more glorious than sunsets, because you have to work much harder to witness them. No “relax with a glass of wine” moments here, but just as sunsets seal the day, early morning egg-yolk sunrises bring with them the promise of unlimited potential. Excited by this thought, I pull back the curtains at the Murray Premises to see fog so thick you could float a sumo wrestler on it. St. John’s is famous for this atmospheric fog, which is great if your life is a film noir mystery but rather inconvenient for sunrise hunters.

Wind, Rain and Fog

Don’t be too upset if your sunset is also draped in fog. With 121 foggy days a year, St. John’s is Canada’s foggiest city, not to mention the windiest. Take comfort that the wind blows away the fog (along with the occasional household pet).

Fortified with strong coffee and hope, I hop in the car and direct the GPS towards Cape Spear. The roads at this time of day are desolate. Lonely metal clangs on the big fishing ships along Marine Drive. I follow directions to Water Street and turn left onto Blackhead Road as the car’s headlights reflect back at me in the fog. There’s a dirty light in the air, as if the sun is feeling ill and doesn’t want to get out of bed. The car passes wooden houses, dispersed farther and farther apart, and just as I begin to relax into the ambience of driving inside a cloud, I catch a movement in the trees up ahead. A large moose jumps out in front of me, causing me to brake hard and wake up everyone within miles with a panicked thumping on my horn. Seriously, Moose, you’ve got the whole province to roam about in, why throw the tourist a surprise party at dawn?

I’d been warned about moose on the roads in Newfoundland, which appear to toy with cars on purpose, like spiteful teenagers annoying authority. The moose vanishes into the brush, leaving me a shot of early morning adrenalin more powerful than any espresso. Minutes later I arrive at the Cape Spear National Historic Site, the parking lot deserted. Clearly, I’m the only person optimistic enough to believe in a foggy sunrise. The wind is howling, the air is wet, I’m cursing luck, weather and moose, when I stop dead in my tracks. The full power of the North Atlantic, crashing into the rocks of a major continent, can have that effect.

Punishing waves as high as buildings smash into the coast, as I gaze upon nature’s never-ending battle of unstoppable fluid meeting immovable solid. Feeling vulnerable and puny, I notice a warning sign, flattened on the ground up ahead. Walking along the coast, wisely sticking to the trails, I listen to the waves, feeling the atmosphere. There are no icebergs and whales this morning. No, on this morning it’s just the Atlantic—the mightiest of all oceans—and one humbled writer, greeting her waves before anyone else on an entire continent. An experience well worth getting up in the morning for.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/capespear

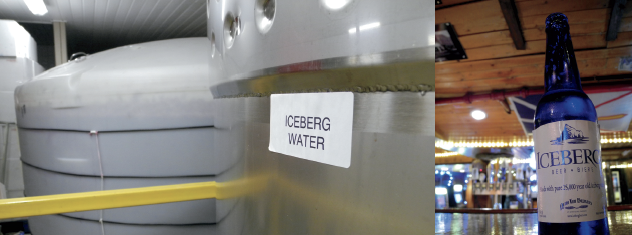

MAKE AN ICEBERG COCKTAIL

More than just the proverbial tip of an overused metaphor, let us salute the iceberg. Sinkers of unsinkable boats, stalking the oceans in search of prey for ironic disasters, icebergs are one of nature’s finest works of art—transient, temporary and just terrific in a vodka martini. There’s a certain panache in mixing millennia-old pure crystal water melted from a roaming iceberg into any beverage. Take St. John’s brewery Quidi Vidi’s Iceberg beer. The label on its distinctive blue bottle reads: “Made with pure 25,000-year-old iceberg water.” If you can apply freshness to beer, it certainly is one of the freshest beers I’ve ever tasted. The blue bottle further enhances the feeling you’re actually drinking mineral water, until four bottles later you realize you’re very drunk.

Thousands of years’ worth of heavy, compressed snow break off from glaciers or ice shelves to form icebergs, and Newfoundland’s Iceberg Alley is one of the best places in the world to see them—from land, boat or kayak. Spring and early summer are the best viewing season, and so I find myself in the windswept seaside town of Twillingate, where iceberg tourism battles to save its ailing fishing industry. To fortify myself for the adventure ahead, I visit Auk Island Winery, which makes locally sourced wild berry wines. Four of their products are made with iceberg water, and the general manager, Danny Bath, assures me he can taste the difference. Inside their winery, a 6,000-litre tank holds the iceberg water, and if you think that’s a lot, you underestimate just how big these ice giants can be. A ship once recorded a 500,000-ton iceberg, while a small 30-ton berg can provide a year’s worth of fresh water for half a million people. You do, however, need a government licence to commercially harvest icebergs, more to protect consumers than for environmental reasons. Icebergs therefore don’t need to be saved, just avoided should you happen to be captain of, say, a luxury cruise ship. Danny talks about the icebergs that visit Twillingate as if they were relatives visiting from Florida. “This one, he was a third of a mile long, I tell you, he was here for five weeks!”

Real Iceberg Vodka?

Canada produces a popular, world-class vodka made with the water of 10,000-year-old icebergs blended with Ontario sweet corn. Manufactured by the Newfoundland and Labrador Liquor Board, Iceberg vodka has won numerous international awards. The makers claim that iceberg water is seven thousand times purer than tap water, which eliminates the need for water purification.

Thirst slaked, I feast on palm-sized fresh mussels at J&J Fishmarket (their fresh seafood platter deserves its own entry on the bucket list) and decide to enlist the help of local skipper Jim Gillard. Since the winds are strong and the rain hard, every operator in town has cancelled their iceberg tours. The friendly folks at the Anchor Inn suggest I call the Skipper, and he agrees to take me out on his seven-metre Seabreeze speedboat named Galactic Mariner. To find the Skipper, all I have to do is drive down Gillard Lane and look for a large observatory.

Skipper Jim was born and raised in Twillingate, a former meteorological technician for the navy and lifelong fisherman in these waters. He’s also an astronomer with a mind-blowing homemade observatory complete with revolving dome (powered by Ski-Doo rails) and a thirty-centimetre LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. Here’s a guy with salt water in his blood and his head in the stars.

We don waterproofs and head out into the bay, rain stinging my eyes. Skipper Jim must have eye shields, for he’s comfortably in his element. He talks about his navy days, fishing, the oceans, his kids, grandkids, whales and icebergs. Skipper Jim’s bucket list is telling: finish the shed, lay down the lobster traps, enjoy the stars. Here’s a man who has everything he needs, right where he needs it. It takes about ten minutes before we see our target.

“Ninety percent of the iceberg sits under the water,” says the Skipper, with that distinctive Newfoundland accent. Icebergs change every day, calving and cracking, with erosion forming distinctive shapes as the ocean and shores gradually wear them down. Our “guest” today is about twenty metres high, with smooth lines, turquoise shades and sharp peaks. It has also formed a flowerpot, much like the earthy examples on display at the Hopewell Rocks (see page 220). This dry-docked iceberg has the majestic design of a meta-snowflake, a true work of genius.

The Skipper keeps his distance. We can hear the ice cracking, which could cause a lower section to roll over and take our boat with it. He pulls up alongside a floating piece of ice and we haul a chunk on board. It is dense, white and concrete heavy, unlike clear normal ice, thanks to the rain that has fallen into cracks. I take a knife and stab the top, the ice shattering into large pieces. The seas might be rough and the rain relentless, but I’ve come a long way to do this, and by golly you can’t let a little weather stand in the way. Not in Canada.

I put the iceberg in a glass and pour some vodka on it. Calving a chunk of iceberg to make a cocktail is something to do before you die, I assure you. The vodka I used: Newfoundland’s own Iceberg vodka, made, of course, with authentic iceberg water.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/icebergcocktail

GET THE CONTINENTAL DRIFT

Arriving at the Gros Morne National Park Discovery Centre, I am ushered into a modern theatre to watch an introductory film about the region. There follow sweeping helicopter shots of epic landscapes straight out of Lord of the Rings, with attractive couples hiking on the edge of emerald green cliffs. Cut to a scene that could have been shot in the fjords of Norway, with park interpreters and locals explaining in earnest voice-overs how this land has spirit, and once you experience it, that spirit will stay with you forever.

I’m always a little nervous about these introductory videos. They often set the bar too high, especially when I peer outside the window to see the now-familiar fog and rain. Why is the weather always perfect in these videos?

I walk around the centre, reading exhibits, learning about the geological wonderland of eastern Canada’s second-largest park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where plate tectonics were first proven as fact. The park is 1,805 square kilometres in size, encompassing large mountains, forests, shoreline, freshwater fjords and bog, and yet I find myself in a small pickle. Despite my name, I’m simply not that into rocks. Tell me that 500 million years ago the earth’s plates collided, forcing its mantle to split through its crust, resulting in Gros Morne’s unique Tablelands, and all I see is a mountain of stone. Then I meet Cedric and Munju, two of the park’s interpreters. We take a short drive to the Tablelands, and stroll along its distinctly barren landscape. Cedric picks up a stone, and his French-Canadian accent drools with excitement.

“Each rock has a story, Robin, and the more we know, the more its story comes out.” He begins to explain the basics of Gros Morne’s importance in the world of science, its sheer uniqueness in our planet’s time and space. Picking up a piece of rust-red serpentinite, he shows me how age-old minerals have been deposited on one side like the scales of a snake. Much like a battle plan, he uses rocks to demonstrate how the continents are continuously in flux. As he does so, the clouds begin to lift and the Tablelands loom above us in their glory, a moon mountain on earth. There’s not much time, so we jump in the car and drive to Trout River, a cliché of a small Newfoundland fishing town.

“It’s always worth driving through here,” says Munju, “just to say hello to the characters.” A man is barbecuing fat sausages inside his smoky garage, rain be damned. Gros Morne surrounds several fishing enclaves, where communities live as they have done for centuries. This is not Disneyland, and these are not re-enactors. The hard reality of the Atlantic fishing industry is on display, unusually located within a national park, and as fascinating to a “far away” like myself as the scenic beauty. Cedric takes us to a viewpoint over Trout River, the wind whipping up whitecaps across a freshwater lake. The ruggedness of the mountains and glacier-cut valleys is something to behold. We drop him off to return to his pregnant wife, and Munju invites me for some wine at her place, overlooking the inlet at Woody Point. She’s just returned from Halifax after a seven-year hiatus and can’t believe her magnificent view for the summer. Some friends arrive, and we head off to the Loft for tasty moose pie. It becomes clear that Gros Morne is more than just a park, it’s a community; and yes, that community definitely has a spirit.

I bid my new friends adieu to make the drive to Rocky Point for the night. Since moose were introduced to the park, they have become quite a handful, especially for motorists. Earlier I had passed a sign on the Trans-Canada Highway that read, rather disturbingly: 660 Moose Collisions. Around the park I’m advised to watch the ditches and pay attention, especially since I’m driving at dusk, when the moose are especially active. After my close encounter in St. John’s (see page 289), there’s little doubt that moose through the windshield would not be as delicious as moose in a pastry.

After a week of rain, the sun at last breaks through for a glorious morning. Newfoundland has finally upgraded from a black-and-white TV to full-colour 3-D. It’s a perfect day for the park’s signature experience, a two-hour boat cruise up the Western Brook Pond. After I enjoy a relaxing half-hour walk over boardwalk and wild bog, the boat floats up this freshwater fjord between towering 600-metre peaks and cascading waterfalls. The natural beauty rightly stuns everyone on board.

Yet it’s not the Western Brook, nor the Tablelands, nor the great company in Woody Point I’ll remember most. It’s stopping off at Broom Point, walking ten minutes on Steve’s Trail through a tree tunnel, and emerging to a panoramic view of the aquamarine coast, black mountains and white beach all to myself. Damn it, that promotional film was right: there is a spirit to this place, and I’ll never forget it.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/grosmorne

REWRITE THE HISTORY BOOKS

History is written by the victors, conquering their version of events into hard fact. Yet every once in a while the rug gets pulled out from under us, and we’re forced to re-evaluate the past. For example: Every kid in America knows that Christopher Columbus was the first European to discover the New World, in 1492. Well, thanks to a couple of tenacious Norwegians and a little outpost on the northern tip of Newfoundland, the textbooks have been revised.

The Icelandic Sagas, dating back to the tenth and eleventh centuries, told stories of “Vinland,” a land of wild grapes, located in the west beyond Iceland and Greenland. The sagas told how Vinland was visited and settled by Vikings, although there was never any proof to back this up. Some theories suggest that, prior to Columbus, the Chinese traded with indigenous Americans, and even that Irish seamen traded on the American coast. A lack of physical evidence sinks as many theories as the Atlantic sinks boats. The fact that there exists a Central and South American demigod who sailed in from the ocean—tall, white, red-headed and -bearded—certainly suggests European influence in the Americas in ages past. Yet without proof, the historical record of Columbus held true.

In the 1960s, Norwegian adventurer Helge Ingstad and his archaeologist wife Anne Stine Ingstad combed the eastern coast of North America searching for physical evidence of Norse settlement. After many red herrings along a coast rich with cod, they happened upon a small, isolated fishing community called L’Anse aux Meadows. When they described to locals what they were looking for, they were surprised to be led to a series of raised mounds. The locals had attributed them to indigenous people, and the kids who played on them called them the Indian Camps. Over the next eight years, the Ingstads’ excavations uncovered undeniable proof that this was in fact a Norse settlement dating back to CE 1,000—almost five hundred years before Columbus. Working in often brutal weather conditions, they discovered eight complete house sites and the remains of a ninth. Parks Canada took over in the 1970s, and when UNESCO awarded its first World Heritage Site to Canada in 1978, the archaeological and historical significance of L’Anse aux Meadows won the day.

“Ya know, you definitely have some Viking in ya,” says the colourful site interpreter, Clayton Colborne. (My blue eyes and red-tinged beard certainly suggest some interesting breeding in my European Jewish heritage.) Clayton was born and raised in the tiny community of L’Anse aux Meadows (population 25) and used to play on the archaeological site as a kid. Today, his bearded, bright-eyed face adorns the Parks Canada pamphlet inside their modern Visitor Centre.

It’s a grey, foggy day, but the drive here from Gros Morne National Park was pretty enough, dotted with fishing communities. The landscape looks like tundra, but Clayton tells me that’s only because all the trees close to the road have been cut down. Homes still need a good supply of wood to make it through the long hard winter, and the nearest tree usually does the trick. Despite the solid tourism traffic, Clayton reckons the actual town of L’Anse aux Meadows—dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, when the French ruled the shoreline—will probably disappear. All the young folk have moved on.

After learning about Norse migration and other information from the Visitor Centre’s exhibits, we walk along a wooden boardwalk into the field, passing beneath a striking sculpture called The Meeting of Two Worlds. “Full circle, ya know,” explains Clayton. “When the Norse arrived and interacted with the locals, it was the first time two branches of humanity met in 100,000 years!”

Was L’Anse aux Meadows Vinland?

The latest archaeological evidence suggests that Vikings travelled south from L’Anse aux Meadows to the St. Lawrence River and into New Brunswick. Vinland, according to the Norse saga, was a country where wild grapes flourished, and New Brunswick is the northern limit for such grape varieties. Nobody knows why the Norse returned to their shipping base at L’Anse aux Meadows, packed up and sailed away to Greenland, never to return.

All that remains of the excavations themselves are mounds, grassed over like burial plots. The Ingstads discovered many artifacts confirming Norse settlement, including a bone knitting needle, a bronze fastening pin and nails made of a type of iron common in the British Isles. Farther along, Parks Canada has reconstructed a Norse hall, hut and house out of sod, as they would have looked one thousand years ago. A re-enactor shares tales around a fire inside, and it isn’t hard to imagine the cold, brutal conditions these early settlers had to endure. Perhaps this explains why the settlement was abandoned after a decade’s use, the houses burned down. The Norse left, never to return. Perhaps this was only a way station en route to a larger, yet-to-be-discovered community, the Vinland so named because of the wild grapes that grew there. Perhaps it was abandoned because of a hostile relationship with the Natives, since we can agree Vikings were not the most peace-loving of people.

It’s a mystery that remains to be solved. In any event, the only known evidence of European settlement in North America aged into obscurity until a Spaniard arrived hundreds of years later and reintroduced Europe to the “New World.” In addition to experiencing the beauty of a stark landscape, and my new understanding of life from another millennia, I depart L’Anse aux Meadows enriched with Clayton’s stories, and the satisfying feeling that a tiny Canadian village has proudly rewritten North American history.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/lanse

SLEEP IN A LIGHTHOUSE

Paddling along the shoreline, Ed English gives me a lesson about Atlantic storms. “I went over to the west coast and watched a storm blow in from the Pacific. They told me it was pretty bad, an eight or nine. Well, we kayak in those kind of waves.”

Clearly, Ed is not your average hotelier, and his four-star Quirpon Lighthouse Inn is not your average hotel. Built in 1922 on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland, the lighthouse overlooks a natural passageway that creates a feeding ground for marine life. Migrating roughly three thousand kilometres south from Greenland, they’re joined by floating hills of solid ice. This is the start of the province’s Iceberg Alley, and one of the best places to see these natural marvels drifting on their slow, melting death march.

It’s early June—peak iceberg season—as our kayaks skirt the seven-kilometre-long Quirpon Island. Ed bought the lighthouse in 1998, sight unseen, when it was put up for tender by the government. Despite wild weather and other challenges, he’s turned it into a hotel that sleeps twenty-five guests in eleven rooms, from May to October. Quirpon (pronounced kar-poon) has since received rave reviews, especially in international media. “Right now there’s a couple from France, Japan, the U.S. . . . Sometimes I don’t see Canadian guests until mid-July.”

Seagulls are flying above us as the sun tiptoes into view from behind the clouds. We round another corner along the coast and there it is: a single dry-docked iceberg, boxed into the coast like a Viking helmet trapped at the end of a bowling alley. Its two icy peaks tower over us, the middle eroded to reflect water in a bright shade of blue. This mountain of compacted ice looks supernaturally out of place, ten thousand years of frozen water so pure that there’s simply no trace of contaminants.

“Keep your distance, Robin. Towers like that crack off all the time, and besides the wave, you don’t know how huge this is beneath us.”

Icebergs come in all shapes and sizes—tabular, domed, pinnacled, wedged, dry-docked and blocky—and watching them evolve from day to day is part of the fun. Yet Ed advises me never to turn my back on the ice, shape-shifting as it melts and smashes its way to oblivion on the rocks below. Kayakers should face forward, just in case.

We circle a couple of times, picking up some “bergie bits,” small chunks floating in the water. My hands are numb from the cold, so we turn back to the harbour, taking advantage of the favourable wind and current.

Out of our wetsuits, we hop aboard the hotel’s Zodiac to see if we can spot some whales. It’s still early season, so it’s unlikely, but it will give me a better look at the lighthouse from the sea, along with pairs of puffins clumsily flapping about us. It’s calm as a lap pool when we leave, but within minutes we’re cresting over three-metre swells. The water is choppy above the Labrador Current, the cold ocean current that flows south from the Arctic. With the icebergs come the whales—humpbacks, orcas and other species. The bergs herd the fish into the island’s coast, allowing guests to watch whales feed literally right below their feet.

Quirpon Island is rocky, mossy and barren, the lighthouse exposed like a palace guard defending the coast from attacking storms. When storms arrive, guests huddle up in excitement in the dining house, perhaps with hot chocolate and some bakeapple pie. Lighthouses are built to survive hurricane-force gales and monster waves, but the inn’s location does present some challenges. Just last week, the wooden dock was smashed against the shore and is currently being repaired. As Ed points out the heliport, the Zodiac hits a swell and tilts upwards at a 45-degree angle. We both pretend not to notice.

It’s too early in the season and the wind is picking up, so he gratefully turns the Zodiac back to the small, protected harbour. Jacques Cartier and James Cook charted these very waters, and just up the road is L’Anse aux Meadows, where the continent’s first visitors settled. With its history, wildlife and adventure, Quirpon Island provides welcome shelter in the darkest of storms.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/quirpon

GET SCREECHED IN

When Newfoundlanders heard I would be visiting the province for the first time, they didn’t ask me if I would explore Gros Morne or track icebergs. They wanted to know if I would be getting screeched in. The fact that this tradition was born out of the St. John’s bars on George Street, ready to charge you twelve bucks for the ceremony and certificate, is beside the point. To become an honorary Newfoundlander (not a Newfie, for that term is derogatory, unless you’re a Newfie, in which case it’s not), one must get screeched in.

Within a half-hour of my arrival in St. John’s, I am at Trapper John’s, a block from my hotel, just in time for the barkeep to begin the ceremony. Christian’s, another bar in a city that likes its possessive apostrophes, apparently has a more authentic ritual, but they don’t do it on Mondays, and this is Monday night. Thus I enter a mostly empty Trapper John’s, where a couple from the U.K. and a student’s mom are signed up for the evening’s Screeching. To get screeched in, one must listen to the barkeep’s bluster, drink a shot of screech and then kiss a cod on the mouth—or, in the case of Trapper John’s, the behind of a fluffy toy puffin. The screech in question is a type of cheap rum that hearkens back to days of yore when the same barrel might carry both rum and molasses. The sediment that remained would be fermented and mixed with grain alcohol to create a drink designed to blind a telescope. Screech was a term used for any moonshine, but it is now marketed as rum and consumed with great pride by locals—and by honorary locals, for that matter. It is so named because of the sound one makes after consuming it, or the sound in the flap of the sails on a boat, or whatever you’re told by the local who will claim to know these things.

Deed I Is!

Since I assume you’ll be “spirited” long before you decide it’s a good idea to kiss a puffin’s arse, practise the following line to endear yourself to your Newfoundland hosts.

When they ask you: “Is ye an honorary Newfoundlander?”

Reply, with gusto: “Deed I is me ol’ cock, and long may your big jib draw!”

We line up at the bar and the bartender begins his story, which I struggle to understand. It is my first real exposure to the distinctive Newfoundland accent, which rolls like an English barrel, made of Canadian wood, down a Scottish hill. Something about the origins of the rum, aye aye this, ya ya that. We are then asked the following question: “Is ye an honorary Newfoundlander?” To which we must reply, with enthusiasm: “Deed I is me ol’ cock, and long may your big jib draw!”

I shoot back the drink expecting a harsh burn down my throat, and am relieved to find it absent. Back in my university days, I indulged in Stroh rum, which at the time was 80 percent alcohol and could strip the innocence off a club of Girl Scouts. I’ve also had the misfortune to shoot straight absinthe in Denmark, raki in Albania and 125-year-old moonshine in Georgia. Screech, by comparison, is palatable.

The toy puffin, representative of the province’s official bird, has seen many lips, which the bartender goes to great pains to remind us. At this point I tell him about the far more intimidating Sour Toe Cocktail (see page 320), which kinda punches a hole in his sails. He must hate travel writers. Still, I gamely kiss the butt of the fluffy puffin, receive a certificate, and that is that. A highlight of Newfoundland it was not, but at least I can tell Newfoundlanders that, yes, I have been screeched in. Despite the potential for hokiness, every province should have an honorary ritual for visitors. Undeniably, it makes you feel welcome.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/screech

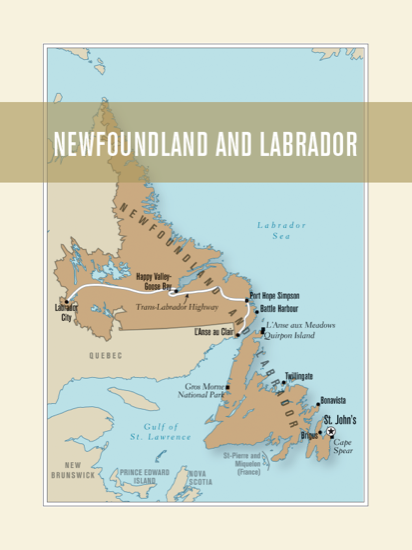

DRIVE THE TRANS-LABRADOR HIGHWAY

“Escaping it all” is an expression many of us can relate to. It implies that we’re locked away in a prison, behind restrictive high walls we have somehow constructed ourselves. Escape also denotes serious effort, an effort that is rewarded with invigorated freedom. Still, can this explain why anyone would drive 1,185 kilometres in almost complete isolation on potholed gravel roads renowned for shredding the very soul of an automobile?

The handy Trans-Labrador Highway Guide, provided by Labrador’s Economic Development Board, has the answer on its front page: “For the adventure of driving through one of the last frontiers in North America. It is on our bucket list as the ultimate road trip.” The TLH is the only road that crosses Canada’s vast eastern mainland. The province was once known simply as Newfoundland, until Labrador distinguished itself in 2001 with a three-letter bridge. And rightly so: Labrador is as large as Japan! It also has just over 26,000 inhabitants, as opposed to Japan’s 128 million. That’s a lot of space, a remoteness that calls out to drivers from around the world, driving modern cars but seeking old-world challenges. One must be resourceful, as capable of dealing with mechanical faults as with persistent bloodsucking insects, bone-soaking rain and moose hell-bent on auto-suicide.

To reach the TLH, you must either drive north from Baie-Comeau, Quebec, or cross the Strait of Belle Isle by ferry from Newfoundland. Either way, you’ll be leaving your cellphone behind and relying on the kindness of strangers (which is legendary in these parts), free loaner satellite phones available at hotels and communities staggered hundreds of kilometres apart. “Be sure to pack water, toilet paper and BUG SPRAY for the drive!” says the summer guide, emphasizing the bug spray as opposed to, say, life-sustaining water.

For the most part the road is narrow with soft shoulders, dusty in the sun but sticky with mud in the rain. Passing trucks are known to machine-gun windscreens with sharp rocks and loose gravel. Carrying a spare tire, preferably two, is essential. Portions of the road are, however, being paved, bringing “civilization creep,” rued by some locals and visitors, although no doubt appreciated by their vehicles. That being said, reports from American and European drivers describe the road from Happy Valley-Goose Bay towards Port Hope Simpson as invoking pure road-trip nirvana—a meandering marvel of packed gravel where, for four hundred kilometres, you feel like the last great driver on Earth.

Canada’s Top 10 Road Trips

It’s a long, arduous road. One-pump gas stations, campgrounds, B&Bs, simple hotels, restaurants and convenience stores provide refuge in small mining towns. The huge hydroelectric dam near Churchill Falls is a welcome roadside attraction in the interior, while the coastal road offers sweeping views of the Atlantic and the icebergs, whales and seabirds that call it home. The guide suggests a 22-hour total driving time (reflecting the condition of the road), give or take a few hours per day for bad weather, construction stops and wildlife viewing. Incredibly, the highway remains open during the winter. The upside is you won’t need a head net and bug jacket every time you venture outdoors. The downside is the frozen, slippery roads and temperatures that can dip to -50°C. Still, expect to encounter large herds of caribou and warm communities living under the glow of the northern lights.

Whatever the season, TLH veterans speak fondly of the pristine landscape, the locals encountered along the way, the fellow travellers enjoying the camaraderie. For allowing us to escape it all and enjoy a true adventure in Canada’s eastern frontier, the Trans-Labrador is another road trip that drives itself onto the Great Canadian Bucket List.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/tlh

DISCOVER THE THREE B’S

Newfoundland and Labrador has no shortage of charming fishing towns, with wooden houses brightly painted against lush green cliffs, sweeping views of the Atlantic and, if the commercials are anything to go by, unsupervised red-headed kids running about. While there are many wonderful places to visit, the bucket list focuses on the three Bs: Bonavista, Brigus and Battle Harbour.

Giovanni Caboto was an Italian explorer, sailing his fifty-ton, three-mast ship under a British flag. In 1497, he spotted North America after two months of sailing west on the Atlantic, famously declaring, “O buena vista!” Thus began the long history of an important fishing town, which once swelled to twenty thousand souls relying heavily on the Atlantic cod industry. Today, the town and rocky shoreline of Bonavista (population 5,000) is a historic landmark, site of John Cabot’s first landing (Giovanni has been anglicized, much like my real name, Roberto Esrockavinni). Bonavista is known for its heritage buildings, museums and famously welcoming locals. Wander down Church Road, with its narrow side streets, watch for whales and icebergs from the lighthouse, explore the wharves and piers, learn about the salt fish trade and hop aboard a full-scale replica of the Matthew, Cabot’s ship that started it all.

What’s with the Pink, White and Green?

You might notice a pink, white and green flag flapping outside houses in St. John’s. The Newfoundland tricolour is not the official flag of the province. It was created in the 1880s as the flag of a Roman Catholic group in St. John’s, drawing on Irish influences, with the pink (or rose) strip possibly protesting against English Protestantism. The flag was controversially taken up by politicians and rabble-rousers, and gained in popularity in a British dominion that once debated whether or not to join Canada. More recently, there was a movement in St. John’s to petition for the tricolour to gain official flag status, but a poll suggested the majority of Newfoundlanders were not tickled pink with the idea.

Closer to St. John’s is Brigus, a traditional English fishing village with a name derived from the word “brickhouse.” This should give you some indication of the Scottish/Irish-influenced accent in this part of the world. Brigus dates back to 1612, when the town attracted English, Irish and Welsh settlers. For a small town, it produced many famous Arctic sea captains in its day, such as Captain Bob Bartlett, whose former home is now the Hawthorne Cottage National Historic Site. Along with other Bartlett family heroes—John, Sam, Robert, Arthur, Isaac and William—Brigus captains were the first to reach the North Pole, sailing with Admiral Robert Peary, undertaking miracle rescues and lighting the path for the shipping legacy of the Canadian Maritimes. Other Brigus attractions include the festive annual Blueberry Festival, Landfall’s Kent College, year-round performances at St. George’s Anglican Church, Ye Olde Stone Barn Museum, and the Tunnel, where early engineers used steel spikes and gunpowder to blast 24-metre-long holes in solid rock to provide easy access to Abram Bartlett’s wharf. You may be in a rush to see Newfoundland, but Brigus wants you to stop, breathe, walk the narrow streets, admire the harbour and chat with the locals.

Getting to Battle Harbour is not quite as easy, but that could be said about getting almost anywhere in Labrador. For two hundred years, Battle Harbour was the salt fish capital of the region, an economic and social centre once known as the capital of Labrador. A government-sponsored relocation program in the 1960s, coupled with the rise of the frozen and fresh fish industries, led to the end of Battle Harbour as a permanent community and the beginning of its restoration as a National Historic District. Buildings, fisheries, churches and century-old houses have been restored to their former glory, creating a remote destination in which to experience the history of the region. Stay in the former homes of fishermen, doctors or policemen, and be entertained at night by seasonal performances and traditional Labradorean hospitality. Battle Harbour may rely on tourists, but not the kind who typically frequent Disneyland. To get there, you’ll have to sail on the MV Iceberg Hunter across the St. Lewis Inlet from Mary’s Harbour, running twice a day.

Three Bs, representing three glimpses into the storied past of Newfoundland and Labrador. Three places to take your time, feel the ocean breeze and turn off the modern world.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/threebees