HAUL A LOBSTER TRAP

Lobster intimidate me. For starters, they look like miniature spider-dragon aliens, capable of slicing your neck off with one swipe of their giant claw, or latching onto your face to impregnate you with acid-dripping offspring. Just look at their undersides: surely that was the inspiration for the monsters in the Alien movies. Spiky legs, sharp edges and two beady eyes thinking, “If I were your size and you were mine . . .” Growing up inland, I never had lobster on the menu, and while I appreciate it is a delicacy for many, so are crickets in Thailand, worms in Venezuela and deep-fried guinea pig in Ecuador. So it is with some trepidation that I step onto Perry Gotell’s boat at four a.m., ready to experience the real working life of an east coast lobster fisherman.

It’s hard work, and the season is short. Six days a week for two solid months, Perry and his first mate, Jerry Mackenzie, motor out into the bay to haul in their three hundred wooden traps and deliver a lucrative load for distributors back at the dock. Through Tranquillity Cove Adventures, anyone can join them for the experience. Blessed with a calm, clear morning, I slip on my waterproofs and get to work before we even leave the dock. A huge blue tub of mackerel must be cut up for each lobster trap. Before the sun breaches the horizon, my rubber gloves are covered in grungy, smelly fish guts. Perry is a third-generation lobster fisherman, and his traps sit at the bottom of the same waters his family have been fishing for decades.

With Perry steering the boat and keying in the GPS coordinates of the traps, Jerry takes a long pole to hook each trap’s buoy, attach it to a mechanical crane and begin hauling heavy wooden crates onto the side of the boat. With dozens of lobster-fishing boats around us, the industry is heavily regulated to ensure there is no overfishing. Licences cost well into the six figures, and while a good day out can yield thousands of dollars, it’s hard, relentless work with plenty of costs to go with it. Perry spends about $1,200 a week just for his bait.

But disembowelled flounder and mackerel are the least of my worries. The traps are literally crawling with huge crabs and panicky large lobsters. Both have sharp claws, protected by strong shells.

“Go ahead,” says Perry. “Stick your hand in and start sorting ’em.”

Lobsters with black eggs are immediately tossed back into the sea to produce new yields. Only the largest crabs are collected, to be weighed and sold; the rest also find themselves sinking back to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The lobsters themselves are put in a sorting bin, from which Jerry measures their size and determines whether they are classed as premium market or standard “canned.” Market lobsters have their claws banded with small blue elastics to prevent them from damaging each other. New bait is set by placing chunks of mackerel on a spike or in a vise inside each trap.

Perry locates a preferable spot and the traps are dumped overboard for another day to do their job. We repeat the above for eight hours, ticking off each of the fifty buoys and mentally counting down each of the three hundred traps. Perry’s ideal is to catch old, huge and heavy lobsters, which he calls “bone crushers” for the size of their claws. At the start of the season, a typical day might net 550 kilograms of lobster, but today, towards the end, he’ll be lucky to get 135 kilograms. Since fishermen are paid by weight, I can’t imagine what it must be like to work four times harder than this.

Meanwhile, I’m still getting over the fear that a crab might sever an artery, or a lobster snip off a finger. “They’re smaller than me and their brains are the size of a pinhead. Outthink, Outsmart, Out . . . oh, to hell with it, come here, you ugly crustacean!” Within a few hours I’m sweeping traps clear in seconds. The sunrise is spectacular, and being able to see the red cliffs of the Island helps with my sea legs, along with the added distraction of listening to Perry and Jerry’s salty dog stories. Each trap presents its own challenge, its own hope of a monster haul or a better one tomorrow.

I’d spent the morning out in the elements, working with nature’s bounty, conquering my fears and learning about a fascinating industry. Hard work, yes, but what an experience. “One guy, he told us fishin’ lobster was on his bucket list,” says Jerry, rinsing the boat. Turns out that guy wasn’t alone.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/lobster

TONG AND SHUCK OYSTERS

I’d tasted P.E.I. long before I ever stepped foot on the Island. After all, P.E.I. mussels, oysters and lobsters are prize items on restaurant menus across North America. I looked forward to tucking into this seafood bonanza as soon as I arrived, especially oysters, that delectable bivalve long associated with decadent pleasure. Some people might argue there’s nothing delicious about consuming a live, raw animal with the texture of a nasal infection. Some people need to get into the spirit of things. To help, experience the life of an oyster farmer in the field—or, more accurately, the water—through a “Tong & Shuck” activity offered by Salutation Cove’s Rocky Bay Oysters.

Co-owner Erskine Lewis takes me out on a boat into the shallow waters of the cove, where oysters grow naturally in prized abundance. After demonstrating the art of tonging oysters from the sandy depth, Erskine hands me the wooden rake–like tool with stainless steel teeth. I carefully scrape the bottom, jostling the tong to loosen up oysters and hopefully bring in a decent haul. It takes a few tries before I get the hang of it, but my hauls are still a fraction of Erskine’s.

How to Shuck an Oyster

We measure the size of each oyster against a simple measuring unit, returning the ones that don’t make the cut. Erskine explains that the difference between choice, restaurant-grade oysters and standard, industrial oysters is simply the shape of the shell. The more round, the more sought-after, and often the less actual oyster to slurp back. Erskine rummages through my haul, selects a choice shell, shucks it right there and hands it to me. No lemon juice, no Tabasco. P.E.I. oysters are best enjoyed raw, fresh and on their own. For this is no ordinary oyster: this is the very taste of Salutation Cove, nature condensed into a food group.

In just a couple of hours, I develop a deep respect for oysters, and the amount of work it takes to grow, harvest and distribute them. The price of an oyster in a P.E.I. restaurant: $2.50. Being able to appreciate them: priceless.

It was time to put the oysters into their more familiar context, and so I enlisted the help of a top-rated local seafood restaurant, owned by the Island’s oyster aficionado. John Bil is a three-time Canadian Oyster Shucking Champion, a man who believes the ocean does all the work, chefs just add heat. His Ship to Shore restaurant, located in scenic Darnley, is jammed in the summer months, and for good reason. The converted former roadhouse serves up only the freshest seafood sourced from nearby friends and colleagues.

After teaching me how to shuck an oyster and demonstrating his own renowned skill (including shucking blindfolded, behind his back), John educates me on the subtleties of oyster appreciation, and sure enough, I begin to taste the coves from which they were harvested, feeling the waves in my mouth. Dinner consists of fresh steamed mussels, fat grilled scallops and a sublime buttery-soft halibut. John recommends a sweet Château de Fargues Sauternes to round off the evening.

Why are P.E.I. oysters so revered? “Oysters are like grapes. A Sauvignon Blanc from Ontario is simply not the same as a Sauvignon Blanc from California,” explains John. From which I conclude that an oyster tonged in P.E.I.’s coves is unlike an oyster from anywhere else, and its taste belongs on the National Bucket List.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/oysters

PLAY A ROUND OF GOLF

There are several things I look forward to doing in the autumn years of my life. I look forward to watching all these TV shows people keep talking about, so I can finally understand what kind of a creature a Snooki is, and why everyone is raving about Mad Men. I look forward to a long career in skydiving, weeks spent playing video games, meditation and, most of all, golf. Not all at the same time, mind you, although that would be interesting.

You see, golf demands the supreme patience, time, skill and budget reserves I don’t yet possess. For those who argue the folly of whacking a little ball a long way to get it into a little cup, I say, “Four!” Yes, I spelled that correctly.

One: Golf gets you outside, in the fresh air, usually in beautiful surroundings.

Two: Golf gets you socially active, because really, it’s not all that important whether you score a birdie or an eagle or any other form of bird life.

Three: Golf is a personal challenge, a combination of mental and physical skill that is easy to learn and impossible to master. Just ask Tiger Woods’s ex-wife.

Four: Golf is punctuated by ice-cold beverages and ends in a clubhouse with more libations, nachos and chicken wings.

Prince Edward Island may be Canada’s smallest, least-populated province, but the facts speak for themselves: At the time of writing, it claims 10 out of the Top 100 Golf Courses as rated by Globe and Mail readers, and 5 percent of the Top 350 Courses in North America. The Island is branded as Canada’s Number One Golf Destination, and received an award from the International Association of Golf Travel Operators as the Undiscovered Golf Destination of the Year. The Island’s thirty-four courses (at the time of writing) are renowned for their natural beauty, variety, design and the fact that they’re mostly a half-hour drive from Charlottetown.

Canada’s Top 10 Golf Courses

Ron MacNeill, Executive Director of P.E.I.’s Golf Association, tees up with his favourite golf courses in Canada:

Take the Brudenell River Golf Club, one of the Island’s most popular courses, dotted with lakes, ponds and gardens. Here I have the opportunity to learn a few tricks from LPGA pro and resident Island golf expert Anne Chouinard. Considering my experience is mostly limited to hacking the carpet off minigolf courses, Anne is impressed by my enthusiasm. She moved here from Quebec for the fantastic Island lifestyle along with the world-class courses and recommends anyone with a love of the game do so as well.

We proceed to play a round, the course buttressing against a gorgeous coastline, surrounded by the tranquility of Brudenell Provincial Park. At par-three, I somehow manage to skip my golf ball twice over a water hazard and into the rough. Anne tells me Phil Mickelson did that once on purpose, which I take as a compliment. On the sixth hole, I’m pretty sure I scored a puffin, penguin and pigeon, which is definitely quite the feat. This demands further celebration back at the clubhouse, with nachos and cold beer. Despite Anne’s best efforts, I have a lot to learn if I want to master this game. Before I die, there’s no place I’d rather master it than on Prince Edward Island.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/golf

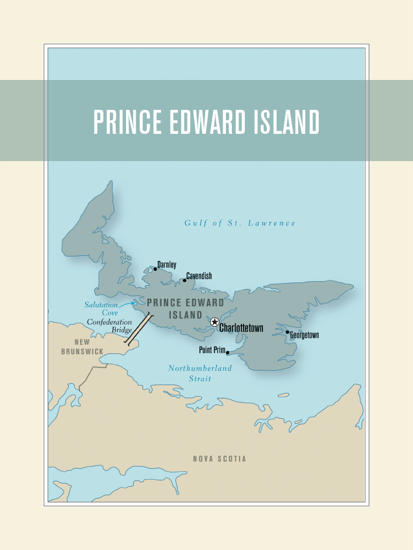

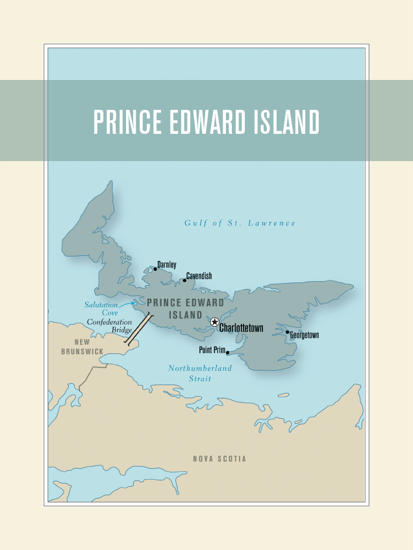

CROSS CONFEDERATION BRIDGE

At the birth pang of Canada, when the founding provinces gathered for the Charlottetown Conference, tiny Prince Edward Island was only accessible by ferry. It may have been Canada through and through, but it wasn’t physically connected to Canada, and winter ferry crossings could be notoriously dicey. A century later, a debate raged about the merits of building a massive bridge to connect the Island to the New Brunswick mainland. The Islanders for a Better Tomorrow argued for the economic benefits of building such a bridge, in terms of both trade and tourism. Friends of the Island felt their lifestyles were under threat and said that not enough research had been done (or indeed could ever be done) to justify the expense. They even tried a legal blockade, but lost when a judge ruled the environmental assessment was adequate. Finally, it came down to a vote in which Islanders were asked if they were in favour of replacing the ferries with an unspecified alternative. In January 1988, a resounding 59.4 percent voted yes to the fixed link. Four years and one billion dollars later, the 12.9-kilometre Confederation Bridge opened for traffic.

Many years later, I found myself in a car about to make this remarkable crossing. It was summer, so the fact that this is the world’s longest bridge over ice-covered water didn’t impress me. Nor did the pricey round-trip toll, although if there’s one bridge that doesn’t give you much of an option, this is it (ferry service was discontinued when the bridge opened). Once I had passed the toll on the East Bridge Approach, the fact that I was on an engineering marvel that once employed over five thousand people and boosted the province’s GDP during construction by 5 percent was kind of lost on me as well. What impressed me deeply was my car cruising at eighty kilometres per hour, surrounded on either side by the cold, dark waters of the Atlantic. The architects had thoughtfully curved the bridge to ensure distracted drivers like myself would pay attention to the road, and not launch off the bridge to add motor vehicles to the marine life below. The highest curve—known as the Navigation Span—is 60 metres above seawater, which is ample height for cruise ships and tankers to pass underneath, between piers spaced 250 metres apart. For those more nervous than myself, rest easy: there are 22 surveillance cameras, 7,000 drain ports, emergency alarms, strict speed limits and a surface designed to minimize water spray. The bridge was built to last one hundred years, by which time we should be making the crossing in flying cars anyway.

Confederation Bridge is more than just a homegrown mega-industrial project, full of impressive numbers and statistics that hopefully kept you entertained. It’s an umbilical cord of national pride, a symbol of democracy, and a fast, efficient way to get to a truly lovely destination.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/confederation

HARVEST SEA PLANTS

Writing in a pirate voice is not the same as speaking in a pirate voice, but I’m going to give it a shot anyway: “Yargh! The sea holds a rich bounty of deliciousness, yargh!”

I was hoping the wonderfully named Gilbert and Goldie Gillis would also speak in pirate, since they comb the nearby beaches for buried treasure, albeit treasure of a different sort. They greet me at their B&B, which, like many houses in P.E.I., is surrounded by lawns so immaculate one could relocate the courts of Wimbledon here. The couple are so sweet and earnest I want them to adopt me. Together they have lived here much of their lives, married in the shadow of the same Point Prim lighthouse that Gilbert’s grandfather once kept, the oldest lighthouse in the province.

Get to the treasure, yargh!

Quick Guide to Edible Sea Plants

Dulse Soft and chewy, distinctive taste and colour, requires no soaking or cooking, great in soups and sandwiches.

Irish moss Bushy red plant, traditionally boiled to release carrageen, a natural gelling agent used as a thickener in food and cosmetics.

Sea lettuce Leafy, dark green with distinctive flavour, good raw but can be bitter when cooked. Used in soups and salads. High in protein, iron and fibre.

Kelp Grouped in the same family as algae, typically used in Japanese or Chinese cooking to flavour stews and soups, or served as a pickled garnish.

The Gillises have been harvesting seaweed and crafting seaweed dishes for generations, an art and hobby they now share through a program called Seaweed Secrets.

“We want to introduce people to the medicinal and nutritional value of all living sea plants,” explains Gilbert, and proceeds to do so. We hop in his pickup truck and head over to beautiful Point Prim, the calm sea sparkling in the sun. It’s low tide, so we scamper onto some rocks to see what’s stacked on the ocean shelves. Irish moss, dulse, kelp, sea lettuce—it looks like rotten veggies, the stuff you avoid when swimming, or the gunk that might get tangled in your onboard motor. Gilbert begs to differ.

“Look at this Irish moss. It has carrageenan, which is used like gelatin,” he says, picking it off a rock. The moss is rich in nutrients and can be used in all sorts of dishes. Gilbert gets excited when he spots a plant called devil’s shoelace. When it dries out, it can be added to salad to add a taste not unlike crispy bacon. Then there’s gracilaria, a sea plant that grows on the shells of oysters and mussels. Goldie is famous for her Wild Island Teriyaki Pickled Seaweed made from the stuff.

Back at the B&B, the Gillises have assembled an edible Sea Plant Museum in their garden barn with the aid of a botanist. I tuck into a bag of dried sea lettuce, an alga that is high in protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals. It tastes like mouldy salt. Although sea lettuce is widely eaten around the world, traditional lettuce can feel safe for now; but then again, typical lettuce might not give you that Gillis gleam. Goldie looks radiant, her skin smooth and her hair full of body, all attributed to homemade cosmetics made of, what else, sea plants.

In the kitchen, Goldie’s got some seaweed vegetable soup on the stove. None of the plants really look edible until they reach her kitchen. She gives some moss a thorough rinse and puts it in a blender. It’s then whisked with sugar and vanilla, poured into a base of breadcrumbs and baked. Topped with fresh cream and homegrown rhubarb confit, the result is a custard-like tart that’s as good as any I’ve ever tasted. Not bad for the stuff I was walking on just a couple of hours ago on the beach. We toast the sunset with a sea-plant buffet (damn, those are some fine pickles) and the fact that every day edible treasures are being washed up on the beach. Yargh to that!

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/seaplants

MEET ANNE OF GREEN GABLES

Long, long, long before Harry Potter and Twilight, another epic children’s book series crossed into the mainstream to become an international publishing phenomenon. It followed the life and misadventures of a red-headed, freckled orphan with sparkling green eyes. Set among the rolling green fields and small-town shenanigans of Prince Edward Island, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, and the eight sequels that followed, immersed readers in the daily lives of early twentieth-century P.E.I. citizens. Written over a period of nearly fifteen years, the books followed Anne’s evolution from scrappy kid to educated young lady to poised and upright citizen, from age eleven to her late fifties. Anne resonated around the world, with over 50 million books sold, numerous accolades for her author and the distinction of being both a Canadian and a Japanese cultural icon. Montgomery’s genius lay not only in the richness of her characters but also in her descriptions of the world in which they operated. Prince Edward Island’s allure as a destination is assured with anyone who reads Anne of Green Gables, including school kids in Japan who continue to do so. I too was required to visit the fields of Cavendish and Avonlea as a student in South Africa. No surprise, then, that thousands of Canadian and international visitors beeline to the inspiration behind the book, along with a range of attractions honouring the Maritimes’ most famous literary hero.

Anne of Japan

Canada’s best-known fictional character still resonates around the world, which is why, growing up in South Africa, I had a prepubescent crush on Megan Follows. But the adventures of the feisty orphan really hit a nerve in Japan, where she is known as Akage no An, literally “Anne of the Red Hair.” Anne’s independence strongly appealed to Japanese girls confined by society, and Prince Edward Island’s natural setting appealed to their sense of fantasy. Ever since the books were first translated in the early 1950s, Anne has become a Japanese superstar. You can buy her products, watch her on TV and visit a Green Gables theme park in Ashibetsu City, Hokkaido.

Green Gables Heritage Place is just part of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Cavendish National Historic Site. Visitors can explore the original farmhouse, which belonged to cousins of Montgomery’s grandfather, along with the Haunted Woods and Lovers Lane that inspired places of the same names in the books. Green Gables continues to receive around 350,000 visitors a year. In the capital, July to September sees the annual production of Anne of Green Gables—The Musical at the Charlottetown Festival. Adapted from the book, the musical has been running for five decades and is performed at the Confederation Centre of the Arts. A half-hour’s drive away you’ll find Avonlea: Village of Anne of Green Gables, a historical village that re-creates the life and times of Prince Edward Island in the early 1900s. Character actors and horses and buggies roam about the village, with visitors popping into musical kitchen parties, plays from the books, and Anne-branded chocolate factories and ice-cream parlours. If you get thirsty, grab a bottle of official Anne-branded raspberry cordial, her much-loved bright red drink.

Yes, enterprising Anne, in the form of the Anne of Green Gables Licensing Authority Inc., is not one to let a merchandising opportunity pass her by. Neither would P.E.I.’s provincial government, which owns half of the corporation, the other half owned by Montgomery’s descendants. Hence the trove of Anne-branded merchandise available at the Anne of Green Gables Store, eagerly snapped up by Japanese tourists. For reasons I’ve been unable to dig up, the Japanese love Anne as much as Alice in Wonderland, which is why you’ll probably see Japanese tourists hanging about the site of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Cavendish home, some of them in full costume.

If you don’t know Anne of Green Gables, or have no interest in the antics of conservative, religious Maritime society, you’re free to swap this item for something like, say, a visit to the sweeping Greenwich Dunes in Prince Edward Island National Park. This rare coastal dune system and its adjacent wetlands have beautiful walking trails, and a long white wooden boardwalk that glows with life at sunset. But when it comes to realizing a fantasy world, kudos to P.E.I.’s Anne attractions for living up to our imaginations.

START HERE: canadianbucketlist.com/gables