The survivors of the Race of Man fled south after the war, rebuilding the homes and cities that were lost, trying to create life, rather than destroy it. —Shea Ohmsford

he Southland’s isolationist stance would not have been possible if not for the fact that the territory encompassed within the Southland contains both fertile farmland and areas rich in metal ores. The quality of farmland in the South is unsurpassed, save by that of the Sarandanon in the West, and the quality of its metal ores are matched only by those in the mines of the far North. The combination allowed the Southland to provide both food and industrial goods for its people without resorting to trade with the other Races.

he Southland’s isolationist stance would not have been possible if not for the fact that the territory encompassed within the Southland contains both fertile farmland and areas rich in metal ores. The quality of farmland in the South is unsurpassed, save by that of the Sarandanon in the West, and the quality of its metal ores are matched only by those in the mines of the far North. The combination allowed the Southland to provide both food and industrial goods for its people without resorting to trade with the other Races.

Arishaig, the capital of the Federation, is also the Southland’s youngest and most modern city. Called the “Jewel of the Federation,” it sits far to the southwest, below the older, more industrialized cities of Wayford and Stern. Boasting a population of almost one hundred thousand people, the city lies on the west bank of the Rappahalladran River. Built over the town of the same name, Arishaig was rebuilt and modernized in the aftermath of the War of the Warlock Lord. The newly created Federation needed a capital, and none of the older cities would do. Tax monies raised by the new government were used to transform the sleepy town into a city fit to house the Federation control center. Arishaig, alone of all the Southland cities, was rebuilt to a master plan. It alone has roads paved with brick, flagstones, and cobblestones instead of the normal dirt and gravel. Because Arishaig’s focus is on governmental business and trade, most manufactured and farm goods are shipped from the other Southland cities into Arishaig for use by its residents. Specialized craftsmen and tradesmen thrive within her borders.

At the center of Arishaig is the Governmental Compound, dominated by the large, ornately carved stone capitol at its heart. Towering over the other state buildings, the capitol’s gracefully carved and ornamented upper archways, adorned with intricate stained-glass windows, overlook the ministry buildings to either side. Though smaller, these buildings—the Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Labor, and Ministry of Trade—are all the work of a skilled designer. Adorned with fluted columns, frescoes, stained-glass windows, and elegant statuary, the entire administrative complex is designed to create a sense of awe in anyone entering the main gate of the walled compound. A broad walkway cuts through immaculately kept gardens toward the capitol, where it joins an esplanade passing before each of the ministry buildings. Grand staircases front each building, adding to the sense of authority exuded by the area. Clustered nearby are other, smaller edifices that house governmental offices or serve as residences for governmental officials and their staffs. A walled park with guarded gates and sentry posts to prevent uninvited visitors from gaining access to the grounds surrounds the entire complex. Only those with documentation or an invitation are allowed entry. It is ironic that the Federation, the government of the people, has more protection around its capitol than any of the monarchies of the Four Lands—old or new—ever required around their palaces.

Within the heart of the capitol, past the massive entrance rotunda, is the great round theater where the Coalition Council sits when it is in session. The room, known as the Council Room, contains a lower circle of seats for the main body of the council, centered on a raised dais. There is an upper balcony for seating invited guests during open sessions. The perimeter of the room is decorated with murals depicting Man’s heroic struggle for survival in the aftermath of the Great Wars, as well as some of his greatest victories since that time. The mural depicting Southwatch was removed after the Shadowen War.

The Prime Minister and his staff use the west wing of the building. It contains day apartments and offices, as well as various smaller council rooms and briefing areas. The east wing is used by the council members and their staffs and is similarly designed, but with more rooms on a slightly smaller scale.

A dedicated cadre of elite Federation soldiers guards the complex as well as the politicians within it. There are no unguarded corridors within the public areas of the governmental complex. Each of the ministers also has a household private guard. When outside their residences, they are always accompanied by at least two of their personal guards.

To further ensure both the safety and the secrecy of the government, a series of concealed underground tunnels was built connecting the Council Room and the Prime Minister’s chambers to the various ministries. No politician ever has to be seen making deals with another. It is doubtful if most of the people of the Federation, or of Arishaig, know these tunnels exist.

The rest of the city is designed to radiate outwards from the glory of the central complex. Outside of the Governmental Compound’s high stone walls, a series of small open parks extends for about fifty yards beyond the walls. From the capitol area, wide paved roads radiate toward the outer edge of the city like spokes on a wheel. Other roads cross and crisscross these main thoroughfares in a pattern that tightens toward the outskirts of the city.

Nearest to the governmental compound are the large walled estates belonging to various diplomats and council members. These estates often consist of several buildings set amid manicured grounds, centered on great manor houses. A series of well-maintained gardens separates the estates and larger houses. Open to the public, these parks all contain grand fountains and statuary carved by the finest artisans in the Southland.

Farther out are the homes and businesses of tradesman, craftsmen, and merchants. This area also contains shops and eating and drinking establishments of all types as well as the better class of brothel. On the riverfront side of the city, this area contains the docks for river trade boats and warehouses for goods sent from the other cities as well as various riverfront shops and taverns.

On the north and west sides, beyond the trade district and toward the outer edge of the city, are the less affluent areas, which include hovels for the poorer workers and the less reputable brothels and taverns. Beyond the poverty areas, the city gradually flattens into farmland and forest areas.

From her clean, carefully ordered city center, with its modern buildings, artfully controlled gardens, and paved streets, to its secret passageways, Arishaig is designed for power. Control, order, power, and secrecy—the qualities that are the spirit of the Federation are embodied in the bedrock of Arishaig.

Believed to have originally existed as townships in the age before the First War of the Races, Wayford and Stern were the first settlements reestablished after that war. Both were built deep in the southern plains near river routes and farming country, but far away from the other Races. At this time, the South was mostly made up of tiny farming communities, which relied on the larger towns for trading their crops and procuring manufactured goods. Wayford and Stern grew from villages into industrialized cities and trade centers supporting the farming communities around them. They were each governed by a council and protected by an armed militia made up of citizens and local farmers.

Now, as part of the Federation, they are under the control of the Coalition Council, represented by their elected council members, and protected by a garrison of the Federation army. Federation rule brought with it efficiency of government and a renewed emphasis on manufacturing that led to greater growth and employment. They increased the number and quality of roads between cities to allow faster wagon traffic, but the roads within both Wayford and Stern are still primarily dirt and mud, except for those near the garrison and the governmental offices, which have been covered with gravel.

According to official Federation records, the population of each city hovers between eight hundred thousand and one million. Most of the people within Wayford and Stern are tradesmen, general laborers, or shopkeepers. The only way to become a tradesman is through the apprentice system. Most shops, regardless of the product, are controlled by a master craftsman who employs journeymen and apprentices beneath him, each hoping to eventually earn the master rating and a shop of their own. Unskilled laborers not looking to apprentice can find work in the larger warehouses or serving municipal needs. These days, though, anyone not employed by a guildsman is likely to be conscripted for the Federation army. Dying is considered unskilled labor.

Each city is built around a central plaza, once the village green, with governmental offices nearby. The rest of the city is divided, rather haphazardly, into warehouse and storage districts, shops and manufacturing districts, the tavern district (which also contains inns and brothels), and the residential district. Many people live where they work, in quarters built over or near their shops. Only the more well-to-do citizens have separate homes within the residential areas. The poor either live in the back rooms of the shops that employ them or in rooming houses in the tavern district. The very poor live on the streets, though any that are able-bodied are certain to be snatched up for the war effort.

If Arishaig is the “Jewel of the Federation,” Dechtera is its grime-encrusted workhorse. Located north of all the other major Federation cities, Dechtera sprawls across the arid central plains that run south of the Prekkendorran Heights. The largest city in the Four Lands, Dechtera is also the least attractive. By day, the smoke belching from its thousands of foundries can be seen for miles over the southern plains. By night, its furnaces glow red like the fires of the underworld.

Almost as old as Wayford and Stern, Dechtera was originally established as a mining town, located between the ore-rich deposits of the southern hills and the great western forest. During the First War of the Races, the need for weapons and military equipment spurred its growth into a premier manufacturing center, home of the finest metal-smiths in the Southland. It was here, during the Second War of the Races, that the legendary Sword of Shannara was made by the master smith Uprox Screl.

The forest is long gone, sacrificed to the voracious hunger of the insatiable furnaces, but the mines have grown ever larger and deeper. By the time of the War of the Warlock Lord, most of the surface ores were depleted and the shafts were extended deeper into the earth, increasing the dangers involved in mining the needed ores. Tunnel collapses and subterranean gas leaks were regular occurrences. It became more difficult to find workers willing to risk their lives for the small amount of pay allocated to mine workers. During the years of Federation expansion, the mines of Dechtera were infamous for consuming lives almost as fast as its furnaces consumed coal. The Federation began conscripting prisoners of war as slave labor to work the mines. This solved both the labor problem and the question of how to eliminate the prisoners. Killing them outright might have alarmed the population, but everyone knew that miners died all the time.

In the aftermath of the Federation-Dwarf War, almost a third of the Dwarf nation met their deaths in the mines. While a few of the labor camps have been converted and modernized for use by Federation convicts, some of the original sheds used to house prisoners during the Dwarf War still stand on the plains outside the city. They are grim reminders of the atrocities committed in the name of human domination, for while it was the Shadowen who instituted the program that nearly destroyed the Dwarf Race, it was often Men who carried it out.

Uprox Screl

Uprox Screl, Master Smith, was the embodiment of the heart and soul of Dechtera. Arguably the finest swordsmith in the Four Lands, he almost refused to cast the blade that became the Sword of Shannara.

A powerfully built but gentle man, Uprox was honored for both his skill and his hard work. Born near Dechtera, he moved to the city to learn the smithing trade, working his way up from apprentice to master in less time than most. His craftsmanship was highly prized. By the time he was thirty he perfected the art of making fine blades as strong as iron, yet light as tin. When word of his skill spread, buyers flocked to buy his pieces. Soon the sale of his work enabled him to build his own smithy and buy a home outside of town, away from the smoke and soot, in which to raise his family.

But one day a buyer returned to tell him of the marvelous carnage his blade had wrought. The warrior was delighted, but Uprox was heartsick. Uprox was an artist, who loved shaping steel—he had never really thought about the pain his creations could inflict. He began to realize that his beautiful lightweight blades were being used as terribly efficient weapons of death. The more weapons he made, the more it ate at his soul, until he could no longer find joy in his work. He tried to make other things, but all anyone wanted were his famous blades. By the time the Druid Bremen found him, he had given up metal work for woodcarving.

The Druid convinced the smith to cast one more very special blade, a weapon that would have no equal—one that would save lives rather than end them. A sword forged with magic.

It took three days of preparation and one long night of casting to make the great sword. Legends are still told throughout Dechtera of the night when green magic burned in Uprox Screl’s forge, spirits danced in tune with his hammer, and a hand with a burning torch rose out of the fires to embrace the molten blade.

By dawn, Druid and smith together had forged the last and greatest weapon Uprox Screl would ever make, and the only one that was destined to save lives: The Sword of Shannara. Uprox was the first and only smith to forge a sword with magic in the history of the Four Lands. But as it does with all things, the magic changed him. Within a month, he took his wife, children, and grandchildren, and left Dechtera forever.

Uprox Screl, master smith who forged the Sword of Shannara.

He settled in the Borderlands, in a village above the Rainbow Lake. Changing his name to Uprox Creel, he lived out his life in peace, never guessing that his heroic descendants, Panamon Creel and Padishar Creel, would both become part of the history of the sword that was his best and last creation.

The mines are still active, supplying the ores needed for the ongoing war effort, but now the majority of the laborers are Men, usually prisoners, who serve out their sentences in the dark depths of the mines. Conditions have improved in that fewer workers die from the labor than during the Shadowen period, and adequate food and shelter are provided to ensure the survival of all but the weakest, but the work is still arduous, the conditions still hostile, and death still a constant threat.

While the mines may seem like a passageway to the underworld, the city itself often resembles artists’ images of the nether regions. The fires of the great foundry furnaces burn night and day, belching out clouds of smoke and soot. The combination of the fires and the heat-retaining smoke cause the temperatures inside the city to remain several degrees above that of the surrounding plain. The resulting soot and ash coat everything with a dark gray pall. Those who can afford it live in the suburban and rural areas on the outskirts of the city to avoid the soot and the heat.

Unlike Arishaig, or even Wayford and Stern, Dechtera was built to no set plan. It has simply grown as needed. Foundries and shops, warehouses and brothels stand side by side along the dirt and gravel streets of the huge city. Open areas are often piled high with scrap metal or raw ore. Alehouses and taverns dominate the central area of the city, but even there, the occasional small blacksmith shop can still be found. The clang of the hammers and the roar of the furnace can be heard day and night. The larger foundries and smithies run two shifts to avoid having to cool the furnaces or bank the fires. The fuel to feed the fires, hard coal and wood, is brought in from mines and forests on the Eastland borders.

As dirty as the city appears, the creations of the artisans and craftsmen who live there have no equal in the Southland. From simple tools to fine weapons and complex machinery, all are made here. Unlike the conscripted miners outside the city, the people who live and work in Dechtera do so because they choose to. Most of them are craftsmen who have found their own type of magic in the science of metallurgy or in the joy of shaping and honing a fine piece. From the lowest apprentice to the most highly skilled master smith, all take pride in their work. Even the shopkeepers and tavern owners take pride in the work Dechtera produces, for they know the Federation cannot find its way to the future without them.

Balanced between the Southland and the Borderlands, the Highlands of Leah are a community separate from either, yet claimed by both. While technically part of the Southland, Leah’s isolated location has allowed it to retain its individual identity for most of its history

The aftermath of the First War of the Races left much of the Race of Man discouraged and seeking new homes within the South. Most men fled deep into the South, in an attempt to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the memory of their bitter defeat. But a small group of hardy individuals, led by a man named Tamlin Leah, stopped running when they discovered the wild beauty of an isolated upland just south of the Rainbow Lake. The land was heavily forested and full of game, yet protected on all sides by natural barriers that would discourage visitors. The land eventually took on the name of its first family and became known as the Highlands of Leah.

It is easy to imagine how these settlers, worn and travel-weary from the escape to the South, had been caught up by the rugged splendor of the lands as they rose above the surrounding forests and marshlands. Some legends claim that Tamlin Leah was a warrior who wanted a safe place away from the rest of Man because he and his small band of friends had been among those who opposed their Race’s push for world domination. Others say that he was a skilled hunter who found in the Highlands a land, plentiful with game, that he and his family could love and protect.

In either case, Tamlin and his family and friends found their new home, far from any existing towns, on a high plain that overlooked the lowlands and forests around them. There they built a village. The isolated location was no hardship. Between its game-filled forests and fertile soil, Leah was completely self-sufficient. The village prospered and, in time, grew into a city. That city in turn spawned its own outlying hamlets.

By the Second War of the Races, men from Leah were fighting side by side with those of the fledgling border outposts in an effort to stop the southward advance of the Northland army. Their battle cry, “Leah! Leah!” was heard often on those bloody battlefields. Many towns and villages fell under the assault, but the Northlanders were stopped well short of the Rainbow Lake and Leah. The legacy of the fighting sons of Leah began with their battles against the Trolls in that war. Once the war was over, the people of the Highlands proclaimed the elder Leah as King, thereby becoming the first monarchy south of the Dragon’s Teeth.

Menion Leah, hero of Kern.

The new king created a standing army, headed by the survivors of the War with the Warlock Lord, which was dedicated to the protection of the people of Leah and of their rural neighbors. He built the city into a walled fortress large enough to protect all the citizens of his land. “So long as there were Leahs on the throne,” he vowed, “there would always be warriors ready to defend the Kingdom.”

For the next six hundred years, the Leah family ruled in an unbroken line of succession, beloved by the people as benevolent caretakers and lauded for their attention to the well-being of their people and their land. The Leahs were the only government the tiny kingdom had ever known or wanted. Under their guidance the Highlands flourished.

The Sword of Leah

Almost as well known as the Sword of Shannara, the Sword of Leah was originally forged as the Sword of State for the Kingdom of Leah. Bearing the royal markings and colors of Leah, it eventually became part of the royal regalia for the Crown Prince of Leah, to be handed down to the new heir at his coming of age. Beautifully wrought and balanced, the sword was worn across the back in the Highlander fashion in a scabbard of fine leather also bearing the royal seal. It was considered one of the finest weapons in the Southland despite the fact that, for many years, it rarely saw usage outside of ceremonial events.

But the Sword proved itself to be a valuable weapon in the hands of Prince Menion, who wielded it skillfully in many skirmishes against foes, both mortal and not, in the War of the Warlock Lord. He proudly handed his honored blade down to his son and heir, Owain.

Owain Leah retired the honored blade, now battered from hard use, and commissioned a new sword for his heir. But the Sword of Leah was not content to remain in retirement. Rone Leah, Menion’s great grandson, was drawn to the old blade despite its worn and battered hilt and scabbard. The blade was still serviceable, having been given expert care over the years. Rone’s father noticed his admiration of the weapon, and gifted Rone with the sword as a small symbol of his standing as the youngest Prince of Leah. Rone needed a way to protect his friend Brin Ohmsford on her quest to destroy the Ildatch, a quest given her by the Druid Allanon. But Rone and his cold iron blade were no match for the eldritch creatures they had to face. To be her protector he needed magical help. Allanon gave him that help at the shores of the Hadeshorn.

The Sword of Leah

Rone Leah later wrote: “The Druid bade me dip the Sword of Leah into the deadly waters of the Lake. I did not know what to expect. I carefully lowered the blade into the swirling waters until it was completely submerged, being careful to keep my hands clear. As the metal touched the lake, the waters boiled and hissed about the blade as though they were alive. After a moment, the boiling stopped, and Allanon bade me remove the sword from the water. When I did, the polished silver sheen of the blade was gone; it had turned black, covered with the waters of the Hadeshorn, which clung to it, swirling as if alive. I almost dropped the sword to see it move so. But Allanon was not done. Blue druid fire flared from his fingertips along the length of the sword. He said he was fusing the water and metal into one. When he was done, the blade was clean and its edges true. Its surface was a black mirror with murky green pools of light swirling lazily just below the surface. I knew it was magic! But the magic was not just in the blade. I could feel the sword’s power, as I had never done when it was merely iron. It was now a part of me in a way I did not understand until much later, both a wondrous gift and a magical curse.”

The transformation allowed the Sword of Leah to cut and parry magic as well as physical attacks. Rone discovered the sword could now destroy even Mord Wraiths, whose magic made them immune to conventional weapons. A direct cut from the sword turned most magical creatures to piles of black ash. But, as with all magic, it was both light and dark. Its magic created a dependency on the sword that grew with every use.

Rone Leah was the first to taste the magic of the sword. His addiction to it nearly cost Brin Ohmsford her life. He managed to come to terms with his need for the magic in time to aid Brin in the Battle at the Maelmord.

After the campaign against the Ildatch, Rone realized how powerful and dangerous the sword could be, and retired it rather than pass it to his children. It remained in a place of honor in the Palace of Leah, and was one of the artifacts carefully removed before the Federation confiscated the Palace. The magic inherent of the sword became a legend told to the sons of Leah to remind them of the days of their kingdom’s greatness.

Three hundred years later, Morgan Leah requested the old sword. No one else was interested in the ancient relic in its battered scabbard. His father gave it to him, having never used it himself. By this time, the tales of its magic were considered nothing more than a way to explain the strange black finish on the blade that never dulled. Its scabbard had been replaced many times, and the hilt half as many, but the blade was still sharp and true. Morgan simply wanted a good blade; preferably, one that would remind him of the legacy his family had lost to the Federation. He was doubtless surprised, during his first battle with a Shadowen, to discover that the magic was real. But Morgan also discovered the dark side of the sword’s power. The magic’s use drained him during long battles, and bonded him, body and soul, to the sword. He later wrote: “The sword seemed to be using me even as I was using it. I thought it was killing me, but I could not stop.”

The sword’s power was not invincible, however. In a desperate battle against the Shadowen in their Pit in Tyrsis, he shattered the blade while escaping. The remnant of the magic saved him in a battle with a Shadowen Spy at the Free-Born Stronghold at the Jut. The sword remained broken until the elemental Quickening restored it upon her death as a reward to Morgan for his love and bravery.

Morgan went on to use the restored sword’s magic against the Shadowen in the battle of Southwatch. He also carried it during the battles to liberate the Eastland, though its magic was not needed, merely its steel.

After the Federation was driven from the East and the Borderlands, the Sword was again retired and put on display in the Leah manor house as an honored part of the Leah heritage. It remained there for nearly a century, until Corran Leah gave it to his oldest son Quentin to use on his voyage on the Jerle Shannara with the Druid Walker Boh.

The magic of the sword has kept the blade in mint condition for hundreds of years. It is a magic that responds only to the threat of other magic. It cannot be activated by will or for simple curiosity. As a weapon of both metal and magic, the Sword of Leah has served the need of the brave sons of Leah, even as they have served the need of the Four Lands in battles against dark magic.

By the time of the War of the Warlock Lord, Leah was the oldest kingdom in the Southland. The Crown Prince, Menion Leah, acquitted himself with honor during the war and is credited with saving the people of Kern and helping to defend Tyrsis during the final battle with the Warlock Lord’s forces. After that war, Leah formed an official alliance with Callahorn and the Borderlands. Menion cemented that commitment by marrying a daughter of the former kings of Kern.

Protected by their isolated location, the Highlands were never attacked directly, yet the Leahs continued to pass the knowledge of battle and hunting from father to son so that skills honed in the wars would not be lost. Though they never had to defend their own borders, the warrior princes of Leah and their descendants carved a path of honor through most of the major conflicts within the Four Lands.

Unfortunately, their courage and fighting skills proved useless against the enemy that finally took their kingdom. Nine hundred years after Leah was established, the oldest monarchy in the South fell without a battle, devoured by the Federation. Overpowered and outnumbered by the Federation war machine, the King of Leah gave up his throne without a fight rather than endanger his people in what would have been a useless massacre. In exchange, the family members were allowed to keep their freedom and most of their lands. The Federation made Leah a protectorate, abolishing the monarchy and installing a provisional governor and cabinet. They disbanded the army of Leah and stationed a garrison of soldiers to maintain order. Though Leah was a small kingdom, the Federation believed that its army, and the independent nature of its people, posed a threat to Federation rule. It was also seen as a stepping-stone to control of the Borderlands.

Controlling Leah was difficult for the Federation. Though the people showed no outward signs of disobedience, small terrorist actions, many of them masterminded by sons of Leah, plagued the occupation force and the provisional governors. At one point the Palace was even burned to the ground. It had been commandeered for use as the governor’s mansion, a use that many within Leah found distasteful, though none would say so publicly. The Governor and his family escaped but never managed to find the arsonist. Sixty years after the Shadowen War, the Federation was driven out of the Borderlands. A few years later it was no surprise to anyone that the most recent provisional governor seemed eager—almost grateful—to finally relinquish Federation control of Leah and escape back to Arishaig.

Rather than reinstate the monarchy, a council of elders was formed, with the head of the Leah family given a seat on the council. There are rumors that the senior Leah was offered a crown and refused it, only reluctantly taking a seat on the council. It is his son, Coran Leah, who now sits as First Minister, leading the people much as his ancestors did, despite the change of title. His sons, Quentin and Bek, have already proven that they too are part of the legacy of the courageous sons of Leah.

Thick gray stone walls surround the perimeter of Leah, the capital of—and only city in—the Highlands. Gates and gatehouses are set into the wall at the four points of the compass, though the majority of the traffic travels through the main entryway at the West Gate. Though it never had to repel an attacking foe, the city was built to be a fortress haven for the people of the region.

Smaller than Tyrsis or the great cities of the deep South, Leah is a sizable metropolis in comparison to the tiny hamlets and sparse population of the surrounding rural region. It is the only Southland city of any size north of the Prekkendorran. Within the walls, homes, shops, and taverns are nestled among trees, ponds, and flowering gardens. The main thoroughfare, a well-packed dirt road wide enough for two wagons abreast, enters the city proper at the West Gate. The road is lined with small shops and markets until it reaches the inner city, where it opens onto parks and residences.

In the days of the monarchy, the road led to the Palace, a grand two-story mansion set into a grove of hickory trees amid an estate of manicured lawns and fragrant gardens, screened from the street by high shrubs and vine-covered iron gates. The Palace, though quite tiny if compared to the Palace of Tyrsis, was comfortably spacious, built of stone and hardwoods with a sizeable Great Hall, boasting the largest stone fireplace in the Highlands. Its many rooms were large and decorated with tapestries and hunting trophies. The kitchens contained large fireplaces suitable for roasting wild boar or venison, and even the servants’ quarters were warmed by individual fireplaces. Most of the furnishings were made from hand-carved wood or bone and upholstered in leather or furs. The workmanship was unequaled in all the Southland.

After the Palace was burned, the provisional governor was forced to abandon the estate. The land was left empty for forty years, with only the crushed-rock walkways and burned foundation stones to mark where the Palace had once stood. Though officially still Federation property, Leah family retainers tended the gardens. For over 250 years, the Leahs lived outside the city walls on their country estate, where they raised cattle. But fifty years ago, when the Federation finally left the Highlands, Coran Leah’s father reclaimed the land confiscated by the Federation government, and built a new two-story home on the site of the old Palace.

The new manor house is much simpler than the Palace of Leah, with far less housing for servants and armsmen. Yet it is still the largest home in the city. Multiple eaves and dormers set off its long rooflines and deep alcoves, though the hickories that used to add such charm to the original building have never completely recovered from the fire. Each of the major rooms has a stone fireplace for warmth in the winter, though none are as large as the one originally built in the Palace’s Great Hall. In place of the Great Hall, the manor house has a spacious dining hall and several large comfortable drawing rooms, which are often used for council business. The decor is still primarily wood, bone, and leather, though increased trade had added to the variety of materials used by the craftsmen who furnished the house. Unfortunately, many of the original furnishings confiscated by the Federation were lost in the fire or confiscated by the Federation and sent to Arishaig.

Across from the old Palace grounds, on the opposite side of the main street, is the city park. Covering approximately fifteen acres, the park is graced with a small central pond, with many paths and seating areas placed among flowering shrubs, trees, and gardens. Beyond the park, narrow streets of hard-packed dirt spread outwards to the city walls. Most of these streets are lined with all manner of shops, markets, taverns, and a few inns. The number of inns has increased over the last century, as more travelers have come to Leah. In the early years, visitors were rare, and most of the city’s residences were located within the protection of the thick walls. Now the outer city sprawls away from the walls, and homesteads and farms blanket most of the once-open high plain. As one travels away from the city, homes and small residences gradually give way to large estates, sheep, cattle, and horse farms, and eventually large cooperatives maintained by the citizens.

To the north, the hillside rises to meet the highland forest that extends over much of Leah. Woodsmen’s cottages and a few homesteads have been established within these woods, but most of the small hamlets and villages of Leah are situated in open meadows or upper plains hidden within the hills, though a few habitations and cattle farms have been established on the grasslands to the west.

The majority of the land belongs to the Leah family and has been left as wilderness, with an occasional hunting lodge or trapper’s cottage hidden in the trees. The finest of these lodges was built in the days of the monarchy for the use of the royal family and guests. Hidden in a stand of pine at the edge of the Highlands, it was unknown to most outside of Leah, especially the Federation, who cared little for venturing outside the walls of the city unless forced. Built to be a base for hunting and fishing in the mist lakes, the lodge became a favored refuge for the sons of Leah during the years of the Federation occupation.

Built to last, the lodge was constructed of timber and stone, with stone floors and walkways and a large open central room with a high vaulted ceiling framed with pine timbers. The lodge looks much as it did when built, with a well-stocked ale bar to one side and a huge stone fireplace dominating the rest of the room. Most of the original leather and wood furniture remains, though many of the pieces have been repaired or refinished over the years, and the kitchen is still well supplied with staples and equipped for handling game and fish. Hunting trophies have been added to the walls, changing and multiplying as each Leah has adjusted the decor to match his personal tastes.

One of the most luxurious features of the lodge is located outside its walls. Approximately a hundred yards to the rear of the lodge are several small clear blue spring-fed pools, used as bathing pools. The pools provided a refreshing end to the most exhausting hunting expedition. For those who craved something even more exotic, mud baths were located about a mile away from the main lodge. They were not used as often as the pools but were very popular on hot summer days.

The land surrounding Leah has always been its first line of defense. To the west, beyond a border of shrub-covered grasslands, lies the Duln, a thick-forested wilderness, and the swift Rappahalladran River. To the north, a mass of cliffs overlooks the great pool of the Rainbow Lake. The south and east are well protected by the dead wasteland known as the Lowlands of Clete, and beyond that, the dense mass of the Black Oaks and the impenetrable Mist Marsh.

In the years of the monarchy, travelers from outside the region rarely visited the Highlands. Travel from the west was possible only by those who knew the trails or who had excellent Tracking skills. There were no established trails. The local villagers who regularly traveled to Leah used their knowledge of the area to follow existing deer trails through the forest of the Duln wilderness.

The southern and eastern approaches to Leah were guarded by the Lowlands of Clete, a dismal, treacherous bog that, on the east, connected the Highlands to the Black Oaks, an ancient forest of giant oaks that stretched for over a hundred miles south from the marsh at the edge of the Rainbow Lake.

The nearly impenetrable wood was over twenty miles wide in most areas. Considered the most dangerous forest in the Southland, it stood like a wall between Leah and the Lower Anar. The great oaks were so numerous and their branches so thick that it was impossible to see the sky from the ground. The citizens of Leah, who were born in the forests of the highlands and grew up traversing the Duln, avoided the Black Oaks whenever possible. They believed the forest was alive with ancient magic trapped there since the Great Wars or before. But the greatest danger was the unnaturally huge wolves that ruled its dark domain, preying on the unwary. Over the years, more than a hundred people fell victim to the wood. Most died as a result of mishap, starvation, or the wolves, but some died from unknown causes.

During the age of Federation occupation, roads were built through Clete and the Black Oaks. Hundreds of man-hours were spent clearing the huge trees and filling the bog with gravel so that the Federation could move its wagons and men more easily to Leah and on to the Borderlands. Once the roads were complete, the wolves were no longer seen in the forest, apparently moving to deeper and safer territory. Travelers discovered Leah and the beauty of the Highlands.

Once the Federation left, there was no one to maintain the roads. The Lowlands of Clete began to reclaim her own. Many roads are now overgrown by brambles or have subsided into the quicksand. The roads in the Black Oaks are overgrown as well, though still useable by carts and larger wagons.

But even the Federation could not build roads through the Mist Marsh. Located between the northern edge of the Black Oaks and the Rainbow Lake, the Mist Marsh blocks the most direct route from Leah to Varfleet. Unchanged for centuries, slime-covered water hides the treacherous bottomless mud of the marsh. The green grasslike covering has lured many creatures to a slow death by suffocation. Thick mist constantly shrouds the marsh, making it impossible to tell location or even time of day. But the bog is not the only danger. Predators such as the Mist Wraiths prey on those who become confused in the constant twilight and wander too close to the swamp. Wolves from the Black Oaks may even feed on victims waiting to die in the unrelenting grasp of the marsh mud. Most wise travelers take the long route to the north and avoid the marsh at all costs.

Though Leah is no longer as isolated as in pre-Federation days, its people still prefer the wilds of the Highlands and their own company to that of the more advanced cities of the south. While they welcome the travelers that have come with the roads, and make use of those roads themselves to see the world, it seems clear that most within Leah would not regret a return to the age of isolation, when the men of Leah could choose their battles and fight for the one thing they never lost—Highlands pride.

Though not a city, Shady Vale is typical in many ways of the many villages and hamlets that make up much of the rural population of the Southland. Located a day’s walk west of Leah, beyond the Rappahalladran and the Duln, Shady Vale sits nestled into one end of a valley ringed by the Duln forest. Its remote location has allowed it to escape most of the battles and difficulties faced by other areas. It was only occupied once, during the Shadowen War. For the most part the farming village has managed to continue almost unchanged through the centuries.

Mist Wraiths and Log Dwellers

Within the Mist Marsh, the fog and the murky waters hide a danger much greater than grasping mud, for powerful creatures of ancient magic lurk beneath the slime. Two such are the creatures known as Mist Wraiths and Log Dwellers. Born of ancient magic and the horrors unleashed during the Great Wars, both lie beneath the waters, buried in the mud of the marsh as they await their prey.

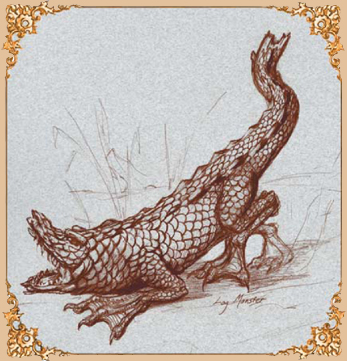

Log Dwellers are so named because they often appear to be partially submerged trees. When disturbed, they erupt from the water to attack with great jaws full of razor-sharp teeth and forelegs with sharp, grasping claws.

A Log Dweller, one of the deadly creatures native to the Mist Marsh.

The Mist Wraith has an affinity for slime, blending into the marsh with its mottled greenish skin. It attacks using its many powerful tentacles to grasp its prey and drag it into the waters to be devoured. Though none have ever been captured, survivors have estimated its average body size to range between fifteen and twenty feet in length, and eight to ten feet in height, with tentacles as much as twice that long. It appears to have a large tearing beak within the center of its tentacles, which it uses to crush and consume its meal.

Despite the size of both creatures, they are tremendously quick and can kill a full-grown man in minutes.

Within the town, single-story houses sit in tidy array along a dirt road that meanders through the valley. It is common to see farm animals wandering among the neatly trimmed hedges and carefully maintained cottages. The valley wall protects the village from the worst of the weather as well as unwanted attention.

The largest building in the Vale is the Inn, built by Curzad Ohmsford twenty years before the War of the Warlock Lord. Constructed of huge logs interlocked over a stone foundation and boasting one of the earliest shingle roofs in the Vale, the Inn consists of a main building and a lounging porch, with two long wings extending out and back on either side. The large lounging room contains benches, high-backed chairs, and several long wooden tables but is dominated by a fireplace on the opposite wall and a bar running down the length of the center wall. Sleeping rooms for the guests were located in the two wings, while the family lived in several rooms in the east wing. The Inn has been partially renovated over the years, though the basic construction remains sound. The Ohmsfords still own the Inn, though they now live in a cottage at the edge of the tree line and allow a friend of the family to run the Inn.

Most of the people who live within Shady Vale make their living by farming. The community is self-sufficient and considers itself large enough to give aid and support to the smaller farming communities and isolated homesteads within the area. Those willing to share their skills often travel to other hamlets and towns to give assistance. Payment is usually made in goods and hospitality. Simple values and a simple way of life are the focus for the people of the Vale.

But unlike other hamlets within the Southland, Shady Vale is more than a sleepy farming village. It is also home to the Ohmsfords, a family whose heroism has been proven in every conflict within the Four Lands since the Second War of the Races.