8

Sand and Imagination II

Stories, Medium, and Muse

One picture is worth ten thousand words.

One part of drawing in the sand that’s really great is that, no matter what I do, no matter how big it is, I have a completely clean sheet of paper, meaning a completely clean strip of sand that I can return to every day, and there’s an incredible freedom in that kind of artwork.

WRITTEN IN SAND

Milpatjunanyi: it’s a word that does not roll easily off Western tongues but carries that promise, common to ancient and exotic languages, of insight and discovery. All languages offer novelty and oddly satisfying demonstrations of the limitations of our own—multiple words to describe what in our language is a single color, for example—and the Pitjantjatjara language of the communities of north central Australia is no exception. Pitjantjatjara is one of the many languages of the many Aboriginal communities in the region around Uluru (Ayers Rock), a natural monument of ancient sandstone. Milpatjunanyi, in the Pitjantjatjara language, means the art of telling stories in the sand. It is a heritage deeply rooted in the land, in journeys, maps, and the dreamtime, a culture of stories whose narratives are actively interwoven with drawing in the sand. The storyteller, often a woman, prepares the canvas by sweeping her arm across the sand; the drawing is generally done with a stick, initially pressed against the narrator to create a ritual connection with the Earth, and the stick is often used as a drumstick to provide accompanying percussion to the story. Men and women have different rituals, different stories, but much of the skill is handed down by the women, using sand drawing as a teaching tool, in exactly the same way that wooden sand trays were used well into the nineteenth century for teaching British children to write. The Aboriginal stories and the accompanying sand icons provide the means of sharing knowledge and tradition within families and between distant communities.

Throughout the world and across cultures, sand has long provided—and continues to provide—the medium for drawing, writing, calculating, teaching, and divining; it is a medium for narrative art and, as we have seen with sand sculpture, art for art’s sake. It is a readily accessible medium for which a finger is the only necessary tool; it is cooperative, yielding, tolerant, reworkable—and ephemeral. Although there are examples where it is trapped into solidity, the intrinsic character, value, and spiritual appeal of sand as a medium is its fragility, its impermanence. And what is startling is not simply the ubiquity of traditions of sand as a medium, but the common threads among the ways in which it is used, the designs and patterns. It seems almost to be part of our collective subconscious.

PATTERNS IN THE SAND

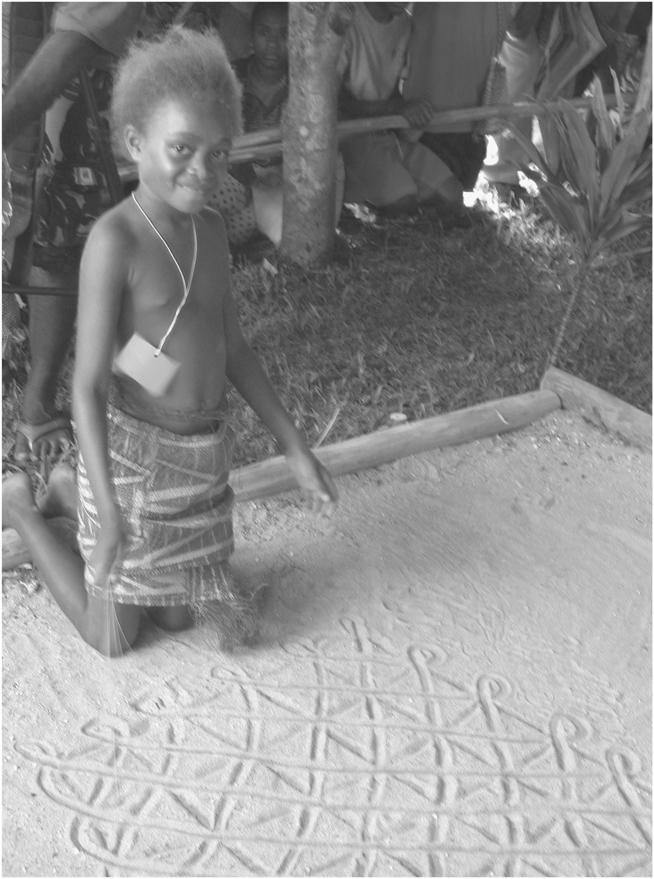

More than 3,000 kilometers (2,000 mi) east of Uluru lie the Pacific islands of Vanuatu, where the tradition of sand drawing has been proclaimed a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” by UNESCO. These age-old visual designs transcend the differences among the eighty languages of the islands. They provide a rich means of communicating and teaching history, rituals, farming methods, family histories, myths, and, indeed, knowledge and stories of all kinds.

The Vanuatu sand drawings comprise a vast collection of intricate designs and patterns, often highly geometrical and made up of interwoven straight lines, curves, and loops—all drawn in a single continuous motion of the finger in the sand (Figure 36). The patterns are ancient and carry layers of meaning; they are mnemonics and records, story illustrations and choreography. As in the traditions of milpatjunanyi, women play a leading role in teaching the art and its forms.

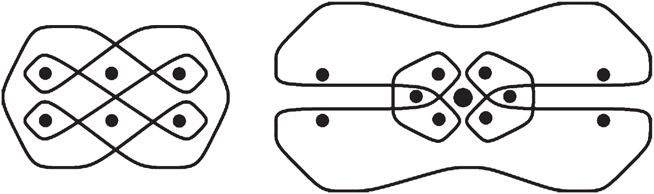

From Vanuatu, travel westward, back across Australia and the Indian Ocean, to south central Africa, land of the Chokwe people. Living mainly in eastern Angola and northwestern Zambia, the Chokwe have a great artistic tradition in different media—pottery, wood, weaving, house decoration—and running through the art are designs and patterns that have their origins in sand drawing, or sona (Figure 37). Many of the designs are hauntingly evocative of those of Vanuatu, and the method of drawing, tracing a single continuous line in the sand to complete the pattern, is identical. The patterns help to tell (and remember) stories, fables, and riddles; they form games and record myths and history. The sand provides the medium in exactly the same way that it does in the desert of Australia and on the islands of Vanuatu.

FIGURE 36. Vanuatu sand drawing. (Photo courtesy of Vanuatu Cultural Centre)

FIGURE 37. Sona sand drawings: the Antelope’s Paw (left) and the Spider (right). (Images courtesy of Erik Demaine, MIT)

In sona, the geometrical grid underlying the symmetry of the pattern is, unlike in Vanuatu, explicit. A matrix of dots, the size of which influences the final design, is made with a fingertip in the sand; then the finger traces out the pattern in a continuous, closed line, no part of which is ever traced over. The designs range from the simple to the extraordinarily complex. Like the old intelligence-testing puzzle where the challenge is to join up a three-by-three matrix of dots with a single continuous but nonrepeated line, the completion of a sona design requires drawing “outside the box” but it also follows a number of fundamental mathematical rules and principles. At key points, the lines appear to reflect off invisible mirrors positioned both outside and within the matrix, and the positions and numbers of these mirrors determine whether or not a given matrix allows the completion of the pattern with a single line. The mathematics of this, together with the question, rather like the “traveling salesman” problem, of what is the shortest line that can complete the enclosure of the dots, is of interest to today’s graph theorists and students of topology and symmetry—as well as “ethnomathematicians.” The Chokwe artists and storytellers are undoubtedly unaware of the underlying algorithms—their designs in the sand speak for themselves and for the Chokwe.

FIGURE 38. Kolam: the Anklet of Krishna (left) and the Ring (right). (Images courtesy of Erik Demaine, MIT)

Now, look at Figure 38—other sona designs, surely? But these patterns come from Tamil Nadu and are typical of that region and other parts of India, each of which has its own tradition and designs. These are kolam, patterns typically drawn outside the door of a house to welcome guests, facilitate prayers, assure the gods of the cleanliness of the house, and generally provide decoration. The designs are drawn by women, using rice flour, powdered rock, and colored sands. If the pattern is decoratively enhanced with colored images, it is called rangoli. During religious festivals, huge and complex designs are made in temples, often with the hope that wedding prayers will be answered. Kolam are commonly made by unmarried girls who keep this in mind, and who have learned the art from their mothers. Competitions are held for skill and new designs, and magazines are devoted to publishing new motifs. The underlying mathematics of matrices of dots and closed continuous curves is the same as that for sona—and the patterns reflect this.

Many of the rangoli designs are unique to the region and distinctly different from those of the Chokwe, but many are virtually identical. The continuity of design from central Australia through southern Africa to India must reveal something of our collective imagination and natural instinct for patterns, and for expressing ourselves using the Earth, especially sand, as our medium.

CIRCLES

Perhaps the most exquisite examples of artistic and spiritual expression through designs in the sand are the intricate mandalas of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Taking days or weeks to make, the mandalas depict harmony, a view of the universe, and a cosmic map; they provide healing, guides to meditation, and a reconsecration of the Earth and its people. And, like milpatjunanyi, sona, and rangoli, mandalas tell stories. The word mandala is Sanskrit in origin, roughly meaning “circle.” The sand used to create one is made today from ground white stone, dyed in a rainbow of different colors. While traditionally the making of a mandala was a private ceremony enacted within the monastery, today Tibetan monks travel the world demonstrating their art. Once the preparatory rituals and prayers are completed, they draw, from memory, the outline of the design and then begin the painstaking process of filling it in with millions of grains of colored sand. They start at the center, slowly working outward, using sand poured meticulously from a small, narrow metal funnel, a chakpur. The chakpur has a rough surface, and the monk controls the flow of sand by causing it to vibrate by running a metal rod over the surface. Exploiting the natural behavior of the granular material, this controlled vibration causes the sand to flow from the funnel like a liquid (Plate 14 shows the construction of a mandala of Vajrabhairava, a wrathful nine-headed deity). The mandala can be 2 meters (6 ft) or more across and contain hundreds of exquisite and colorful images of traditional spiritual symbols—wheels within wheels. The entire design seems fractal, with each grain of sand ultimately a mandala in itself.

Indeed, this intrinsic reference in a mandala to scale and individual grains has been the inspiration for a collaboration between Victoria Vesna, an artist, and James Gimzewski, a nanoscience researcher at the University of California at Los Angeles. In 2004, in their installation Nanomandala, they projected onto a 2.5-meter (8 ft) disc of sand a video that showed sand at gradually increasing and then decreasing scales, from the molecular structure of an individual sand grain to a completed mandala and back again. The installation was accompanied by sounds of the chakpur and of monks chanting, recorded during the creation of the mandala seen in the video. Visitors could participate by moving their hands in the sand as the projection continued, in part on the sand and in part on their own bodies. Vesna commented: “Inspired by watching the nanoscientist at work, purposefully arranging atoms just as the monk laboriously creates sand images grain by grain, this work brings together the Eastern and Western minds through their shared process centered on patience. Both cultures use these bottom-up building practices to create a complex picture of the world from extremely different perspectives.”

A mandala illustrates the Buddhist view of the transitory and impermanent nature of things, and the sand, the medium for the design but itself a transitory and constantly changing material, provides the drama of the final gesture. When the mandala and the ceremonies are complete, the sand is swept up, the design instantly destroyed. The sand is placed in an urn, and half is presented to the audience; the other half is carried to a river and cast into the current, carrying the mandala’s healing to the ocean.

The circular design, the image of circles within circles, labyrinths, wheels within wheels, is common across religions, cultures, and history. In North America, the Navajo use sand paintings in much the same way as the monks of Tibet, to provide healing and blessings, to restore order and harmony when nature seems out of balance. Like the Tibetans, the Navajo have hundreds of distinct paintings and designs, but also, in the same way, they are largely prescribed—the creation of the image is key, not individuality or innovation. Again like a mandala, a Navajo sand painting is accompanied by ritual and is a communal creation, the work being carried out by several artists, starting from the center and working outward, but following the Sun from the east, through south and west, to finish in the north (Figure 39). The dry painting is done on a sand floor, using colored sand together with other materials—stones, charcoal, gypsum, and flower petals. The patterns are symmetrical and contain images of the gods and human heroes, with the eastern side of the circle left open to allow these spiritual beings to enter the design.

After the painting has served its spiritual purpose, like a mandala it is destroyed. The sand is swept away in a sequence that is the reverse of the painting’s creation, buried or cast to the four winds. The permanent sand paintings that are made on glue-covered boards add variations to the original designs, change the colors, or reverse the directions—the metaphor of impermanence of a true sand painting is at its heart, and to make it permanent would be a sacrilege.

FIGURE 39. Navajo sand painting. (Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library, Western History Collection; Mullarky Photo X-33166)

AN IMPERMANENT CANVAS

Whether in the building of a sand sculpture, a mandala, or simply a beach doodle, the transient nature of sand as a medium has deep appeal. The sand castle is washed away, the doodle casually brushed clean, the mandala swept up. In New London, Connecticut, George K. Clarke creates “manhole mandalas” by filling the designs in the cast iron covers in the street with colored sand, to be washed away by the next rain. There are stories, some perhaps true, many no doubt apocryphal, of Pablo Picasso sketching in the sand on a beach; in one, he is pursued by a woman asking for a small sketch, and he obliges by drawing a picture in the sand. Transience and renewal on a grand scale underpin the allure of what has come to be called land art, earthworks that intentionally remind us of a constantly changing landscape.

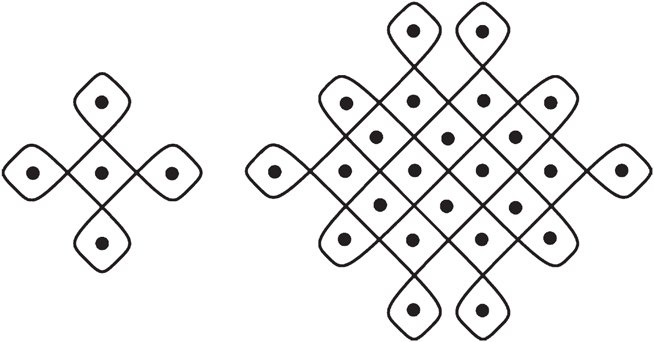

Jim Denevan walks out onto a freshly washed Northern California beach, bends down, and draws a circle, the size of a coin, in the sand with his finger. More circles create a spiral nest, the outer ones growing larger. Using a driftwood stick as his paintbrush, he draws bigger circles in the sand, each one nestling with the previous; the design grows fractally. Denevan does all this freehand—there is no outline, no preliminary design; the artwork simply flows from his mind through the choreography of his movement. His work evokes a Japanese karesansui, popularly known as a Zen garden, with its contemplative design of raked sand. Denevan’s design is monumental, ultimately occupying the entire width of the beach. He uses a large rake to highlight the outline and to fill in the spaces with texture (Figure 40). A few hours later, the tide destroys the art and renews the canvas. For Denevan, the transience is part of the art; it recognizes “some kind of truth about life—what is grand, or what is fragile. . . . Everything is transitioning into something else.” Denevan’s designs are diverse, ranging from huge perfect spirals, to representational images, to complex circles and linear shapes, suggesting a more fragile version of the Nazca lines, the gigantic figures in the Peruvian desert—themselves created by the removal of desert stones to expose the light-colored sand beneath.

The purpose and meaning of the Nazca lines are still a mystery, but if we view them as the oldest form of land art, then it is indeed a long tradition. As a modern form, land art began to blossom only in the 1960s with artists such as Michael Heizer, who sculpted circular designs with his motorcycle in the sand of the Nevada desert and excavated the giant trenches of his best-known work, Double Negative (1969–70). Heizer’s father had been an archaeologist who took his son with him on his expeditions, including to Peru. Was he inspired by the earliest land artists of the Nazca? Another of the founders of modern land art was Robert Smithson, who is perhaps best known for his Spiral Jetty (1970), a gigantic work in earth and basalt; set in the Great Salt Lake in Utah, the spiral is sometimes visible and sometimes not, subject to fluctuations in the water level of the lake. It was Smithson (tragically killed in an air crash at the age of thirty-five while surveying a site in Texas) and his colleagues who demonstrated that art was something that could use materials from the Earth and exist outside an art gallery—producing works of art whose life, whose duration, could be subject to the rate of geological change, slow or rapid. Smithson introduced the term earthworks to describe land art, perhaps inspired by the books of science-fiction writer Brian Aldiss, whose 1965 novel Earthworks described a dystopian future of destroyed soil—robot tankers shipping sand from Africa to other parts of the world to replace soil ruined by human depredation.

FIGURE 40. Examples of Jim Denevan’s work. (Photos courtesy of the artist)

Smithson often employed spirals in his work. His Spiral Hill, created in Holland in 1971, used white sand to highlight a ramp winding around a mound of black earth. What is it about circles and spirals that connects not just Denevan and Smithson but, apparently, all of us? Smithson also played with sand on a large scale indoors. His Mirrors and Shelly Sand (1970) is an 8.5-meter (28 ft) long mound of sand cut at regular intervals by fifty mirrors. By reflecting the sand, the mirrors extend and multiply it, making a mockery of scale.

Land art is very much about scale, from the initial displacement of a grain of sand, a pebble, a boulder to the creation of something monumental—or small. One of today’s best-known land artists is Andy Goldsworthy, every one of whose works is profoundly anchored in the natural world. In Fine Dry Sand (1989), Goldsworthy used sand to describe itself, the sinuous undulating ridges and furrows emulating ripples, waves, and movement. Goldsworthy’s Dark Dry Sand Drawing (1987), a design on a beach, prefigured Denevan’s work. Other artists have used sand pouring from a backpack to draw meandering lines or have created human designs overlapping natural ones in the desert sands of the Kalahari. Enthusiastic and talented amateurs on the beach are also land artists, shaping repetitive designs like crop circles or competing to create images of celebrities. Where land art stops and playfulness begins is a matter of opinion, but all sand works are united by being more or less transient. They are preserved as photographs in books and on the web, but the photographs are not the art. The art, if it still exists, is defined by its context, its connection with the place and the materials, and its expression of continuous change.

Jay Critchley is another artist who has long been inspired by sand. His first works were temporary installations of “sand cars,” which included a sand-encrusted station wagon and Sand Family, a car filled with sand. Visitors to Cape Cod can see—for now at least, but for how much longer is uncertain—his Beige Motel, an iconic American 1950s one-story motor court (originally the Pilgrim Spring Motel) that Critchley has encrusted entirely with sand; the interior houses smaller installation works. The beige theme is evocative of what scientists, combining the spectrum of hundreds of thousands of galaxies, have determined to be the color of the universe. The Beige Motel typifies the symbolism of an impermanent canvas—the structure is due to be demolished. As Critchley says, it is “about temporarily capturing a very fluid substance for a moment in time, a motel about to be demolished, reduced to its earthly substances, mixing again with the sand.”

PERMANENT CANVASES: PAINTING WITH SAND

Land art, as any land artist will tell you, is a messy business; sand is a material that has a habit of behaving as its own rules decree—and of getting anywhere and everywhere. This can also cause problems for the more conventional artist, particularly one whose enthusiasm for painting landscapes in the wild results in exposure to the penetrating whims of blowing sand grains. Georges Seurat at Gravelines, Claude Monet on the beach at Trouville, and Jan Vermeer on the rooftops of Delft involuntarily had sand grains mix with their paints. Also susceptible to granular intrusions was Vincent van Gogh. Painting en plein air, he captured the swirling landscapes and brilliant colors of Provence—along with sand grains borne into his pigment by the Mistral. Even in his early days in his native Holland, Vincent suffered from unwanted additions to his work. In a letter to his brother Theo in 1882, he wrote:

All during the week we have had a great deal of wind, storm and rain, and I went to Scheveningen several times to see it.

I brought two small marines home from there.

One of them is slightly sprinkled with sand—but the second, made during a real storm, during which the sea came quite close to the dunes, was so covered with a thick layer of sand that I was obliged to scrape it off twice. The wind blew so hard that I could scarcely stay on my feet, and could hardly see for the sand that was flying around. However, I tried to get it fixed by going to a little inn behind the dunes, and there scraped it off and immediately painted it in again, returning to the beach now and then for a fresh impression.

Ironically—or perhaps as a reference—when Francis Bacon worked on his Study for “Portrait of Van Gogh” III (1957), some seventy years later, he intentionally added sand to increase texture in the already thick paint strokes.

Bacon was following in an illustrious tradition by intentionally using sand to add texture to his painting. Jean-François Millet, Georges Braque, Salvador Dalí, and Picasso all did so at one time or another. One of the great Surrealists, André Masson, used sand liberally in his paintings. Born in 1896, he was badly wounded in World War I, an experience that is cited as the origin of the conflict portrayed in much of his imagery. Like Joan Miró, Masson made “automatic” drawings, allowing a line to develop freely as, hopefully, a direct connection with the mind of the artist. Pursuing this goal in his painting, Masson would pour and dribble glue or gesso freely onto the canvas and then coat the glue shapes with sand, brush away the excess, and use these forms (“almost always irrational ones,” according to the artist) to guide the rest of the work. His Battle of Fishes (1926), now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is a classic example of this technique. Masson emigrated to the United States in 1939, and his free-flowing style, with gesso and paint dribbled directly from the tube, is said to have influenced Jackson Pollock (who likened his own methods to those of Navajo sand painters).

In art museum shops today, you can buy a sand art kit for kids. The kit consists of paper, glue, multicolored sands, and a sand dispenser, together with detailed instructions, magic sticky sheets, and “special” sand art paper—the spirit of Masson lives on.

Kids visiting Alum Bay on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England, will drag their parents to a variety of carnival amusements that have grown up above the cliffs; among the less gaudy of these attractions is the Sand Shop. Vertical layers of sandstones in the cliffs below have been colored by diagenesis and the infiltration of mineral-rich waters, producing a variety of yellow, red, greenish, and ochre sands. In the Sand Shop are trays of these sands, which the children can pour into a variety of glass containers—lighthouses are popular—to make patterns, a tradition that began when Queen Victoria was presented with patterned sand in a bottle. The designs and execution of the Sand Shop pieces, even in the commercial works on sale, are crude, but not so the bottled sands of Andrew Clemens. Born in the mid-nineteenth century in Iowa and deaf from early childhood, Clemens developed an extraordinary skill. He knew of the place where the St. Peter Sandstone, originally deposited in a shallow sea 450 million years ago, had been stained into a rainbow of colors, from deep red through green to blue. Clemens collected the sands, cleaned and sorted the grains into different sizes, and, with a small hickory stick and a fishhook, placed them, one by one, into bottles to create—without adhesive of any kind—incredibly detailed pictures with shaded tones, geometric designs, and writing (Plate 15). Nothing like Clemens’s work had been created before—or has been since. Used as gifts and custom greeting cards, sold for a few dollars, the surviving examples are now valued in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Sand thus provides the medium for art on all scales. One of the most extraordinary of today’s sand artists who work on the small scale is Willard Wigan, who painstakingly carves from individual sand grains or fragments thereof. An elephant, for example, occupies a fraction of the area on the head of a pin. One hazard of this art is that it can easily be lost through inhalation or sneezing, a serious loss when months of work are involved and the value is significant: his collection recently sold for over twenty million dollars.

SAND ART IN THE DIGITAL AGE

In 1949, a young graduate student in engineering in Miami, Joe Woodland, was determined to develop a method for automating the checkout process at supermarkets. Down at the beach one day, Woodland was idly tracing patterns in the sand, based on the only code he knew, Morse code. His fingers elongated some of the dashes, and the bar code was born. Woodland was ahead of his time: everyday use of the bar code would emerge only much later. Nevertheless, one of the icons of the digital age owes its origin to sand as a medium.

Today, the ability of sand to serve as a three-dimensional, malleable canvas for capturing and displaying information is thoroughly integrated into the digital age. As we have seen, sand has lent itself to this use for millennia—milpatjunanyi and sona are living traditions, and sand tables were not only tools for teaching writing but, on a large scale, continue to be used for military planning. In one form of contemporary sand art, images are continuously sculpted and reformed on a glass plate by the artist’s hands, the whole process illuminated from beneath and magnified and projected. The art is intended to be watched—there are countless video files of these works on the internet. But the digital relationship runs deeper. The installation Nanomandala discussed earlier is but one example of using a surface of sand as a medium for digital imagery.

Mariano Sardon is an Argentinian installation artist who has also used sand and digital imagery in his work. Now a professor at the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, he began as a plasma physicist at the University of Buenos Aires. Starting in 2003, Sardon developed an installation called Books of Sand, after “The Book of Sand,” by fellow Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges, the story of an infinite, constantly changing, and deeply disturbing book. Sardon’s installation is interactive: the viewer’s hands manipulate sand in large glass cubic containers, and at the same time the movements of hands and sand are processed to instantly feed back ever-changing text fragments of Borges’s story plucked from web pages; the text fragments are projected on the sand and the viewer, fluidly changing, appearing and disappearing. In Sardon’s words: “The cubes enclose in a confined space a fragment of the infinite information flowing through the web. It is immeasurable and never ending, like the particles that make up the sand and the codes that form the text. In ‘Books of Sand’ the viewer has the possibility of handling what is immaterial, can grasp an instant of it in the fist of a hand.” The effect is compelling—ethereal, kinetic, shape-shifting, luminous. The viewer, sculpting, pouring, and scattering the sand, appears to create the text.

The journey from science to artistic expression is a common one in the digital age. For some time, MIT has run a Media Lab, where recently SandScape, an installation evocative of Sardon’s work, has been developed: as three-dimensional digital data (for example, topographical information) are projected onto a sand table, the viewer sculpts the sand in response to the data, which, in turn, respond to their manipulation. Sand, as for the native people of Australia, Vanuatu, and Angola, continues its role as a tangible “tactile interface.”

Among other things, Bruce Shapiro builds “shimmibots” and “geyserbots,” and creates works with titles such as Ribbon Dancer, Stratograph, and Sisyphus. Shapiro began his career as a medical doctor but has spent the past fifteen years exploring the relationships between motion control—which he defines as “techniques for orchestrating the movement of machinery and objects”—and art. Salvaging parts from industrial robotics and automation, he builds machines that do extraordinary things, and many of them do these things with sand. His Stratographs are containers that very slowly fill up with colored sand, creating images over the course of an exhibition, perhaps several months in length. His “shimmibots” take Chladni patterns (chapter 2) several steps further, using simple and complex vibrations to create living and evolving patterns in sand. The various versions of Sisyphus, of which there are several generations, take the form of large (up to 3 meters, or 10 feet, in diameter) circular sand tables; in the sand lies a small steel ball, set in motion by a programmed device that drives a magnet beneath the table. The motion of the magnet is controlled by the input either of an original design or of algorithms, equations that Sisyphus translates into graphic reality in a way similar to the generation of fractal images from mathematical equations. The size of the sand grains is critical: Shapiro uses very fine sand to optimize the movement of the ball (whose task, as a result, is less onerous than that of the original Sisyphus, who endlessly pushed a boulder uphill) and the preservation of the terrain it creates. Figure 41 illustrates the results of Sisyphus’s labors; among its stunning diversity of designs are nested circles and spirals—shapes of a seemingly universal, basic appeal.

This is, again, a dynamic work to be watched, not simply looked at—the ball moves sedately but determinedly, as if moved by an invisible but methodical hand. It can take hours or days to complete a sand “etching,” after which, in the spiritual tradition of sand as a transient medium, Sisyphus destroys its own work.

One of the latest incarnations of Sisyphus is on permanent display at Technorama, the Swiss Science Center, near Zurich. It is one of an extraordinary and compelling variety of exhibits at the museum that translate, through technology, materials into art—a fascinating number of which exploit the peculiar and fluid behaviors of granular materials that were described in chapter 2. Technorama, which refers to Sisyphus as “a kind of icon” of the exhibition, carries a series of videos on the web—appropriate for art that is to be watched.

Given the contemplative state it invites in its viewers, Sisyphus has understandably been described as evocative of the raked gravel patterns in Japanese Zen gardens. The performance artist Mona Hatoum has exhibited a work with similar associations: in + and - (1994–2004), a large circular sand pit is crossed by a metal rake that is serrated on one half, smooth on the other; the rake slowly rotates, simultaneously creating and destroying a set of grooves in the sand. It is an automated Zen garden and shares spiritual kinship with Sisyphus.

FIGURE 41. Sisyphus at work. (Photo courtesy of Bruce Shapiro)

Dynamic installation works all over the world explore the interface between art and science by harnessing the strange behaviors of sand in air and water. Every image, every form they create, is unique—and often temporary. The allusive properties of sand are explored in projects like the computer-driven sand etchings of Jean-Pierre Hébert (Shapiro’s early collaborator), the interactive installations of Ned Kahn (Aeolian Landscape, Fluvial Storm), and Martha Winter’s fusing of geology and geometry into three-dimensional canvases of pigmented sand. When the nineteenth-century French mathematician Jules-Antoine Lissajous set up his cord-and-funnel apparatus to trace out in poured sand the ellipses that now bear his name, he little guessed how much more his medium could express.

READING THE SAND: DIVINATION

If certain Taoist elders or ancient Arabic visionaries or Dogon priests from Mali were to watch Sisyphus, SandScape, Books of Sand, or Jim Denevan creating a sand work, they would know exactly what was going on. They would see not art, however, nor technology, but the future.

Geomancy, the art of divination, is a word that derives from the translation of the Arabic term ilm al-raml, the science of the sand. In a wide variety of cultures, sand has been a medium for telling the future. A shallow bowl of sand can be used, the surface smoothed; the person whose fortune is to be told makes shapes and patterns in the sand, the expert interpretation of which defines his or her future. Alternatively, the edge of the bowl can be tapped with a stick and the resulting patterns—vibrated granular materials again—can be interpreted.

In original Arabic geomancy, the diviner used and developed dots drawn in the sand on a board—or simply in the desert—by the person seeking advice. A twelfth-century automated interpreter, a beautifully ornate brass mechanical “calculator” from Damascus, was created to facilitate interpretation of the patterns. The Arabs brought the art of geomancy to Africa, and the tradition continues. Today, complex patterns of lines and dots in the sand—often, like sona and rangoli, displaying fundamental mathematical qualities—are used to answer questions and divine the future. In the Dogon culture of Mali, the priest sets out an elaborate pattern of drawings, lines, and piles of sand, and invokes the sacred fox to visit during the night. If the fox obliges, the pattern of its tracks around the priest’s arrangement is interpreted.

In certain forms of Taoism, divination is accomplished by using sand as the medium in which spirits and deities write. Fine white sand in a large sand tray is smoothed and preparatory rituals are completed. The expert medium enters into a trance, takes a stick, and begins the incantation to seek assistance. If the incantation is successful, the thoughts of the spirit are transferred through the medium and the stick into sand writing. The words and symbols are continually recorded and the sand resmoothed so as not to interrupt the procedure.

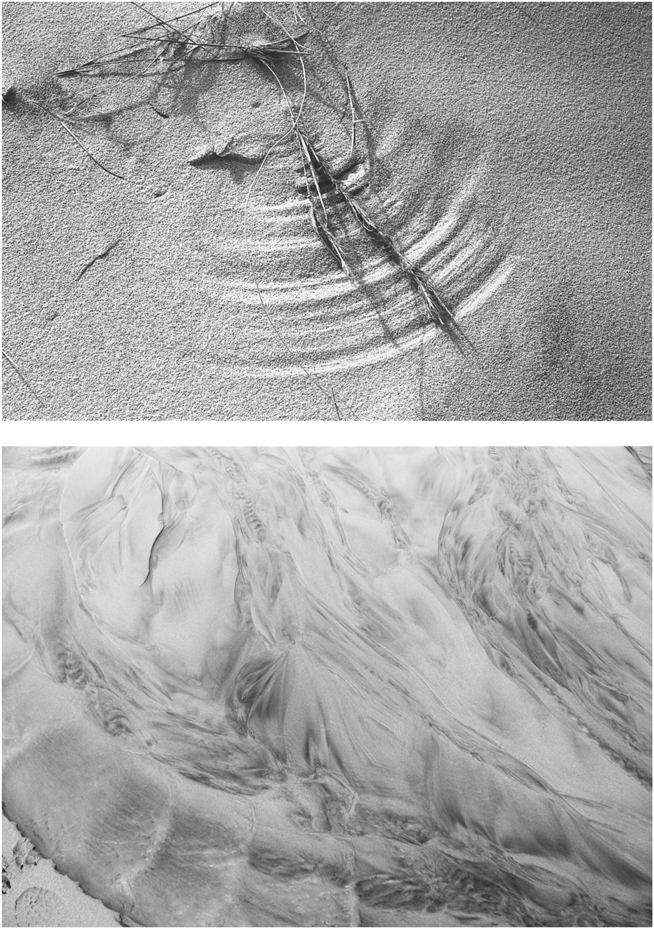

FIGURE 42. Sand designs of wind and water. (Photos by author)

FIGURE 43. The Earthquake Rose. (Photo courtesy of Norman MacLeod)

THE EARTH RESPONDS

Sand is an infinitely expressive medium—and muse—and is widely employed across geography, cultures, and time. It can be used to tell stories of the past and of the future, and to portray the constantly changing present. And as we have seen in the rivers, beaches, and deserts of the world, sand is also the medium for the expression of the patterns, microscopic and gigantic, of the Earth itself, of nature, whose transient designs are themselves art (Figure 42).

On at least one occasion, nature has created its own Zen garden, emulating Sisyphus. In February 2001, in a shop in Port Townsend, Washington, a desktop toy—a sand-tracing pendulum—was set in motion. It was tracing out a simple design in the sand when a strong earthquake began shaking the building. When all had calmed down and people returned, the Earth had traced the record of its shaking in the center of the sand, sometimes now referred to as the Earthquake Rose (Figure 43).