“You need to get up, now,” the bus driver says, looking at fifteen-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. “These other folks need to sit down.”

M. L. (that’s what everybody calls him) stares straight ahead. Why? M. L. thinks. Why should I have to get up? But of course he knows the reason. He’s black, and white people want his seat. They expect it.

He knows what can happen to African Americans who refuse to obey the bus laws. He knows they can be forced off the bus or even arrested. He has seen blacks savagely beaten for less. He looks out the window and sees the sign at the bus stop: FRANKLINTON. He’s ninety miles away from Atlanta and home.

“You need to get up,” the bus driver repeats angrily. He sees only a black teenager—a disobedient black teenager. In the culture of the South, that’s all that matters. It doesn’t matter than this young man plays the violin, enjoys opera, excels at sports, and earns top grades in high school, where he has already skipped one grade and will later skip his senior year. It doesn’t matter that M. L. is a minister’s son who lives in a household with rules, expectations, and discipline; or that he goes to church all day on Sunday and almost every other day of the week; or that he’s often dressed as he is today, in a smart suit. It doesn’t even matter that earlier today M. L. represented his school at a statewide oratory contest.

There’s no innocent explanation for the driver’s demand: He’s not merely asking a polite young man to give up his seat for an older person. One of M. L.’s teachers, Sarah Grace Bradley, who has accompanied M. L. to the contest, is also being told to move.

JIM CROW

Usually M. L. is treated like a prince. He’s a member of the affluent and educated elite of Atlanta, one of the most important cities in African American life. Nearly half of Atlanta’s 300,000 citizens are African American. The city is home to some of the nation’s best black colleges—Clark, Morehouse, Spelman, and Atlanta University—which have attracted intellectuals like the prominent scholar W. E. B. Du Bois. Economically, the black community ranges from business tycoons to sharecroppers. Socially, there’s no more important institution in black Atlanta than the church, and the church where M. L.’s father is pastor, Ebenezer Baptist, has been at the center of the community for three generations. M. L. and his older sister and younger brother are well known within the community because of their father’s position. They’re aware that their family has many advantages not shared by the many black citizens of Atlanta who are kept from c jobs because of racism. But neither their social status nor their affluence protects them from bigotry. M. L. has known it all his life. When he was five, the father of his best friend, a white boy, had forbidden his son to play with M. L. because M. L. was black. M. L. never forgot the shock of that first lesson in racism.

M. L. has inherited his father’s ability to captivate an audience, and it was no surprise that a few days earlier he won a spot at the oratory contest. By this time, the subject of his speech was also no surprise: He was already furious at the injustices Southern blacks faced, and the poverty that resulted from it. The title of his speech was “The Negro and the Constitution.” It called for the full enforcement of laws already in the U.S. Constitution that should have guaranteed equality for African Americans. It demanded access to education, jobs, and health care, all of which were kept from African Americans by local laws—which the Constitution should have overruled—that maintained segregation.

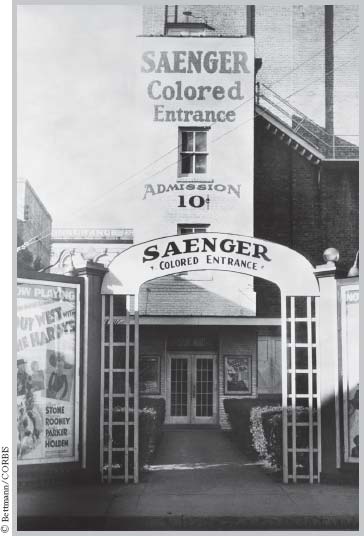

Those laws were known casually as “Jim Crow.” The name came from a character in minstrel shows, a popular entertainment that made fun of African Americans, portraying them as lazy, stupid, and superstitious. White actors played Jim Crow in “blackface” (dark, clownish makeup). There were Jim Crow laws against eating in the same restaurants, drinking from the same water fountains, swimming in the same pools, and, of course, sitting together on buses.

THOMAS D. RICE (1808–1860) CREATED THE 1828 SONG AND DANCE ROUTINE “JUMP JIM CROW.” HE WAS MIMICKING AN AFRICAN AMERICAN STREET PERFORMER.

The first Jim Crow laws were passed a few decades after the Civil War, when political compromises allowed Southern states to reestablish some of the local power they had lost when they lost the war. The laws ignored the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, passed after the war, guaranteeing that blacks were free, that they would receive equal protection under the law, and that they could vote.

Jim Crow laws were designed specifically to make sure blacks stayed poor, uneducated, and utterly powerless to change their circumstances. They also kept the two races physically separated in public. Hypocritically, it was common for even the most admired men in the white community to have relationships with African American women, and these were usually ignored by friends provided the man was discreet. For example, Strom Thurmond, a governor of South Carolina and then a senator from the state, who actually ran for president of the United States in 1948 on a segregationist platform, had a secret daughter who resulted from his relationship with a family maid. This was only made public after his death in the year 2003—when his daughter was almost seventy-eight years old. (Thurmond lived to just less than 101 years.)

A segregated movie theater in Florida. This is the back entrance. The front entrance was reserved for white patrons. Inside theaters like this one, African Americans were segregated into the balcony.

In his speech, M. L. warned that that the whole nation suffers from segregation: “We cannot have an enlightened democracy with one great group living in ignorance. We cannot have a healthy nation with one tenth of the people ill-nourished, sick, harboring germs of disease which recognize no color lines, obey no Jim Crow laws.”

M. L. delivered the speech in his ringing baritone entirely from memory, without looking at any notes. It was a heartfelt speech that had passionately named the abuses suffered by Southern blacks and the remedy for those abuses: fair play and free opportunity. And it had won. Now he feels that this bus driver wants to take that success away from him.

DADDY KING

The bus driver is demanding: “Give these white folks your seat.”

What would Daddy do? M. L. wonders. His father, Martin Luther King Sr., the single most influential person in M. L.’s life, does everything he can to resist the unjust social order. M. L. remembers the day “Daddy King” was pulled over by a policeman for a traffic violation. “Boy,” the patrolman had demanded, “show me your license.” As a holdover from days of slavery, white people in the South commonly called African American men of any age by the condescending term “boy.”

“Do you see this child here?” Daddy had retorted, pointing to M. L. “That’s a boy there. I’m a man. I’m Reverend King.”

Reverend King had arrived at his station in life by his own intelligence, ambition, and hard work. Growing up as a sharecropper’s son, he had seen the very worst that the Jim Crow South inflicted on former slaves and their descendants. He saw whites humiliate blacks, beat them, and even lynch them—hang them by the neck from trees until they were dead—without being punished.

A SHARECROPPER IS A FARMER WHO RENTS LAND BY GIVING THE OWNER A PORTION, USUALLY HALF, OF WHAT’S GROWN. IT’S A COMMON PRACTICE WHERE MONEY IS SCARCE.

Reverend King also overcame family difficulties. He had watched his father regularly beat his mother after drinking too much. When he was fifteen, he defended her by wrestling his father to the floor. The next day his father pledged never to beat his mother again.

Not long afterward, Mike (he later changed his name to Martin Luther) left for Atlanta, determined to rise in the world. He went to school at night, earning his high school diploma and later a degree in divinity. He refused to ride the segregated buses in Atlanta, and bought a car as soon as he could afford one.

He courted and married Alberta Williams, the daughter of Reverend Adam Daniel Williams, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. When Reverend Williams died in 1931, Reverend King took over as pastor of Ebenezer. He was widely known for his fiery sermons, which M. L. sometimes found embarrassing.

By this time Reverend King had built a reputation for himself as a man of integrity, wisdom, and influence. Even white leaders in Atlanta sought his counsel in matters of race. He never hesitated to assert his rights as he understood them. “I don’t care how long I have to live with the system,” he said, “I am never going to accept it. I’ll fight it until I die.”

M. L. sits in his seat, staring straight ahead, not moving a muscle. He knows exactly what his father would be thinking in the same situation. There’s no reason for me to give up my seat.

STANDING ROOM ONLY

The bus driver loses his patience and begins to swear at M. L., but M. L. doesn’t move. I don’t want to fight this man, M. L. thinks, but I will if I have to.

Then he feels his teacher take his hand and turns to see her imploring eyes filled with fear. “We have to obey the law,” she whispers. M. L. can’t do that—he can’t respect this law. But he can respect his teacher. In deference to her, he slowly stands up.

Some of M. L.’s remarks in his speech earlier this day perfectly describe what’s happening now, just a few hours after the ringing applause in the auditorium: “The finest Negro is at the mercy of the meanest white man. Even winners of our highest honors face the class color bar…. [W]ith their right hand [white Americans] raise to high places the great who have dark skins, and with their left, they slap us down to keep us in ‘our places.’”

The bus fills completely. With no seats available, M. L. and his teacher stand for the last ninety miles of the trip home to Atlanta. Years later he would tell people this moment was the angriest he had ever been in his life.