Twenty-six-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. jumps into his car and rushes to the Holt Street Baptist Church on this chilly evening. He knows a crowd is waiting—a crowd that has suddenly asked him to lead them into a dangerous situation. He’s prepared for what he sees as he gets close to the church: A traffic jam blocks the last five blocks of the trip because so many people have come to hear what he has to tell to them. Parking his car, he walks the rest of the way to the church and politely moves through the crowd waiting outside, which reaches the sidewalk. They’re congratulating him even before he begins to speak. They have no idea that even just twenty minutes ago the awesome responsibility had left him at a loss for words. But this whole day has been extraordinary, and he’s determined to live up to expectations. Starting early this morning, the African Americans in this city—half of the population—chose to say, No more Jim Crow. We’ve had enough. They began an extraordinary protest. Then, just a few hours ago, King, relatively new to Montgomery, where he’d come to be pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, was put in charge of leading this courageous movement. In an instant, the course of his life has changed. The pastor of a small Southern church will soon be a national figure.

Luckily, King has thought for a long time about the ideas he is about to express, and for years he has unconsciously prepared for moment just like this one.

THE GOOD SHEPHERD

King has come a long way since that angry bus ride back from the oratory contest. In the summer after that incident, he worked on a tobacco farm in Connecticut, and for the first time in his life experienced the blissful absence of segregation. He sat in the same theaters as white people and ate in the same restaurants. On the train ride home, however, when the train reached Washington, D.C., he had to switch to a black car to continue the ride through the segregated South. He found it all the more disturbing because the change occurred in the nation’s capital.

When he was only fifteen, he enrolled in Morehouse College, thinking he might like to become a doctor or a lawyer. In his last year at Morehouse, however, he decided to become a minister. It seemed to be the best way he could help his people, and it would take advantage of his remarkable oratorical gifts. To further his education he enrolled at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. There he learned about philosophers who had struggled with the same kind of injustice that angered him. He especially liked the ideas of Henry David Thoreau, who argued that moral people should disobey immoral laws by performing acts of “civil disobedience.” Thoreau seemed to be saying that it was not just the right but the duty to disobey laws like the Jim Crow statutes of the Southern states. King was impressed that Thoreau had been willing to go to jail for his beliefs. Then in the spring of 1950, King heard a lecture about Mahatma Gandhi, who had led the people of India to freedom from British rule without firing a single shot. Gandhi had encouraged his people to protest without violence, as a way to shame the British into acknowledging the immorality of their oppression. After many protests and seven years in prison, Gandhi proved successful. King read as much as he could about Gandhi in the hope that he had found a way to defeat the Jim Crow laws he despised.

“UNDER A GOVERNMENT WHICH IMPRISONS ANY UNJUSTLY, THE TRUE PLACE FOR A JUST MAN IS ALSO A PRISON.”

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU, “CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE”

King graduated from Crozer at the head of his class, and decided to go to Boston University to earn a doctorate in theology. There, at the suggestion of a friend, he introduced himself to Coretta Scott, a music student from Alabama. Within one hour of meeting her, King declared she had everything he looked for in a wife: character, intelligence, personality, and beauty. One year later, they were married.

Soon afterward, the Kings faced a difficult decision. Malcolm was offered jobs in northern states, and Coretta was certain her music career would go further there. They were both happy to get away from the insulting segregation of the South, and, thinking ahead to a family, they wanted their future children to be spared that system. But something in both of them wanted to fight segregation rather than escape it. They believed they had an obligation to serve those people who couldn’t escape segregation as easily as they could.

They ended up not just in the South but in the first capital of the Confederacy. The Dexter Avenue Baptist Church stands across a public square from the Alabama State capitol, where, King knew before he first visited his potential home, Jefferson Davis had been sworn in as president of the Confederate States of America. “Here the first Confederate flag was made and unfurled,” King later wrote. “I was to see this imposing reminder of the Confederacy from the steps of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church many times in the following years.”

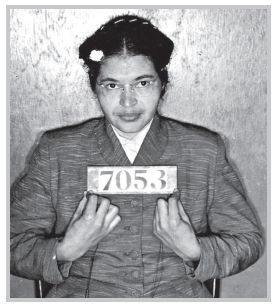

ROSA PARKS

In May 1954, just as King was taking his post at Dexter, the Supreme Court announced a decision that offered hope to those fighting Jim Crow. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the court ruled that racial segregation of schools was illegal.

That decision was the reverse of one the court had made more than fifty years earlier, in a case called Plessy v. Ferguson, which had allowed separate facilities for blacks and whites. The Plessy decision said the separate facilities merely had to be equal. In the Brown decision, the justices said that separate public schools based on race were, for all practical purposes, unequal, and therefore unconstitutional. It ordered the schools to integrate.

THURGOOD MARSHALL, ONE OF THE LAWYERS WHO WON THE Brown CASE, WAS APPOINTED A FEDERAL JUDGE IN 1961 AND WAS RAISED TO THE SUPREME COURT IN 1967.

Black leaders knew that the Brown decision made all of the segregation laws vulnerable to revocation. They began to make plans for new legal challenges against racism.

In Montgomery, one of the most prominent leaders was E. D. Nixon, who, despite just a year of formal schooling, had long been leading effective local protests. Among his many positions, he was president of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), one of the most effective civil rights organizations. (The NAACP had been the driving force in the several court cases that led to the Brown decision.) Nixon and other black leaders decided to mount a campaign against the bus laws, which in Montgomery were even worse than what King had experienced on the ride through Georgia. For example, African Americans in Montgomery had to enter at the front door of a bus to pay the driver, then step back out of the bus, walk to the back door, and reenter there.

Maybe the most absurd fact about this treatment is that three-fourths of the riders on Montgomery buses were black. They should have been treated as the best customers. But that was also a weakness in Jim Crow. Nixon and his colleagues knew that if blacks refused to ride the buses, the bus company would lose a lot of money. If the boycott lasted long enough, the bus company might be forced to accept the protesters’ demands for better treatment.

Nixon also wanted a strong court case against the bus company. For that, he needed to identify an individual case of mistreatment that proved the illegal inequity of the bus company policies toward African Americans. That case came to him by way of an old friend and colleague, an officer of the Montgomery NAACP, Rosa Parks.

Parks, like many Southern blacks, had conducted a lifelong battle against Jim Crow. She understood the bus laws all too well. Once, after paying her fare at the front of the bus, she had refused the driver’s order to get off and reenter at the back door, and she had been physically thrown off.

On December 1, 1955, Parks, a seamstress, finished work and boarded the bus in downtown Montgomery. Following the Jim Crow rules, she sat just behind the section reserved for whites. But then the bus filled up, and when a white man could not find a seat, the driver asked Parks to give up hers.

Parks refused, silently.

“Look, woman,” the bus driver said, “I told you I wanted the seat. Are you going to stand up?”

Parks knew that if blacks were ever going to begin the long journey to equality, someone had to take the first step. She knew she could be ejected, jailed, or even beaten. But she’d had enough. She looked at the bus driver and uttered a single word: “No.”

She was taken off the bus and arrested. By the time she arrived at the police station, news of her arrest had already reached Nixon, who immediately decided, This is the case.

ROAD TO NOWHERE

Over the weekend Nixon and other black leaders, including King, hastily organized the boycott of the bus system. They sent out thousands of leaflets encouraging blacks not to ride the buses on Monday. They specified three demands: for bus drivers to be polite, for blacks not to have to get up for whites, and for blacks to be able to apply for jobs as bus drivers.

King wondered if this rushed protest would work. He knew that for some people, boycotting the bus could mean missing work and possibly losing a job. Monday morning, he drove all around the city, from bus stop to bus stop, to see how many people would feel they had to ignore the boycott. To his astonishment, bus stops all over the city were empty.

That afternoon black leaders met to discuss plans for continuing the boycott beyond the one day they’d planned. A new organization, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), was established to coordinate the boycott. King, new to the city and therefore free of old political entanglements, was unexpectedly chosen to be its head. The leaders then made a plan for a mass meeting a few hours later. King would speak, and if there was enough support from the community, the boycott would continue. The twenty-six-year-old had just been thrust into the most visible position in a protest that would involve the entire nation.

Rosa Parks, in a police mug shot from a protest during the Montgomery bus boycott

A LOVE SUPREME

Now, King steps up to the podium and stares out at more than a thousand faces, knowing that outside the church four thousand more people are listening over loudspeakers.

He now knows he doesn’t need to urge the crowd to act. He doesn’t have to wait until the speech is over to know the boycott will continue. What he needs to do, what he begins to do as he takes the microphone, is urge the people in the crowd to protest in a particular way—the nonviolent way.

As he finishes, the crowd rises as one to applaud him and his ideals.

Victory in the Montgomery bus boycott won’t come as quickly as this day’s events suggest, but it will come, after more than a year of difficulty and sacrifice by the African Americans of the city. Looking back from today’s perspective, it may be surprising that the boycott had to last that long, but many white citizens of Montgomery were determined to fight integration to the end. King himself will become a target for their anger. Most days he’ll receive death threats. A bomb will be exploded on his porch. Finally, the Supreme Court will issue a decision declaring Alabama’s bus segregation laws unconstitutional.

On December 20, 1956—381 days after Rosa Parks was arrested—the boycott will end. At dawn the next day King and some of his colleagues in the boycott, trailed by reporters and television cameras, will board the city’s first integrated bus.

As King steps on, the bus driver will say, “I believe you are Reverend King, aren’t you?”

King will reply, “Yes, I am.”

“We are glad,” the driver will say politely, “to have you with us.”