Working in secret, Martin Luther King Jr. is writing the defining statement of the American civil rights movement. What Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was to the American Revolution—a declaration of equality before the law and a warning that injustice would no longer be suffered—the document King is drafting today will be for those Americans the Revolution failed to free.

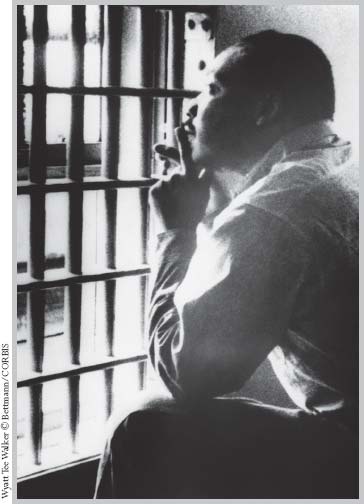

He’s not at his desk at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, nor in a comfortable hotel before a speaking engagement. He’s sitting alone in a cell at the Birmingham city jail, writing on notebook paper smuggled in by one of his lawyers.

Over the clattering of the trains moving slowly along the nearby railroad tracks, he hears a guard approaching the cell door. He hides his work underneath his shirt, then he casually lies down on the metal slats of the prison bed. If I had a mattress I could hide a whole book, he thinks.

His lawyer thinks King is writing a whole book. King has written eighteen pages already and seems to have more to say.

What he’s writing will become known as the “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It’s an answer to eight local white clergymen who have written a public statement criticizing King and the efforts to desegregate Birmingham.

Although King’s reply is addressed to those men, it’s meant to be read by the entire nation. He’s committing to paper every argument he knows for nonviolent protest in the quest for racial justice.

BITTER ALBANY

King doesn’t have to be in jail. Some of the Birmingham authorities would rather he weren’t—they look bad for putting him there. As the civil rights movement’s most famous figure-head, King draws national attention whenever he goes to jail. But he insists: If they are going to arrest him and charge him with a crime, they’ll have to live with the bad publicity.

That insight was something he learned the hard way the previous summer. When he was jailed in Albany, Georgia, the mayor cleverly arranged to have the city pay his fine anonymously. King mistakenly thought a supporter had done it, and he accepted release. King was criticized by people in the civil rights movement for lacking commitment to the cause.

Albany had been a bad experience for other reasons, too. At nearly every turn, the local authorities outmaneuvered the protesters. The police chief, knowing the city was under scrutiny by the media, never resorted to the violence that would normally have occurred. The protesters were duped into postponing demonstrations by the promise of negotiations that never happened. The judge convicted the protesters for disturbing the peace but shrewdly let them off without jail.

When the protest ended, the city remained, in the words of one observer, “a monument to white supremacy.”

King and the SCLC vowed to learn from their mistakes. They had failed in Albany because of poor planning. It wouldn’t happen in their next effort, in Birmingham, Alabama.

PROJECT C

King considered Birmingham “the most segregated city in America.” Its commitment to racism was ridiculous and spiteful. It had gone as far as closing its parks and disbanding its baseball team rather than allow them to be desegregated.

Determined to apply the lessons of Albany to Birmingham, King and his associates planned what they called Project C, for “confrontation.” They focused on the downtown business community rather than all the offenders. They set up workshops to teach nonviolent techniques. They learned which locations would be most effective for a protest.

Being outsmarted in Birmingham wasn’t likely. The commissioner of public safety (police commissioner), T. E. “Bull” Connor, an extreme racist, had been an embarrassment to the city for years. It wasn’t long before Connor’s police used dogs and clubs to attack the protesters. Then on April 12 King and about fifty other protestors were arrested. King was placed in solitary confinement.

That’s where he’s been for three days now, writing.

UNWISE AND UNTIMELY

Shortly after being locked up, King saw a newspaper with the clergymen’s public statement. It infuriated him. They called the protests “unwise and untimely.” They implored blacks to work through negotiation and the court system rather than taking their grievances to the streets. They said that even if the protesters were nonviolent, they were ultimately responsible for the police attacks they suffered. They asked the protesters to ignore “outsiders” like King. “[A] cause should be pressed in the courts…not in the streets,” they said, ignoring the lack of justice for African Americans in the Birmingham courts.

Martin Luther King Jr. sits in a jail cell at the Jefferson County Courthouse in Birmingham, Alabama.

As a final sign of their lack of understanding, they added, “We commend…law enforcement officials in particular, on the calm manner in which these demonstrations have been handled.”

JIM CROW LAWS WERE SO EFFECTIVE THAT IN 1940 THERE WAS NOT A SINGLE BLACK JUDGE OR POLICEMAN IN ALABAMA, GEORGIA, LOUISIANA, MISSISSIPPI, OR SOUTH CAROLINA.

King feels betrayed. He is a clergyman. His father is a clergyman. One of his grandfathers was a clergyman. Do these men not understand the clergy’s role in helping the poor and oppressed? Do they not understand Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence, “all men are created equal…endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights”? King was arrested on Good Friday, one of the holiest days in the calendar for most of the clergy who signed the letter. Do they fail to recognize the religious parallels to this struggle—to the persecution of Jews in Babylon and Egypt, and of Christians in the Roman Empire? Have they forgotten the protests of early Jews and Christians? There is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience, he thinks.

King, sitting in solitary, immediately starts drafting his reply to the clergymen in the margins of the newspaper containing their statement. At first his colleagues were annoyed that King was not addressing more urgent issues, but now they see the potential power of the document.

“THIS DECISIVE HOUR”

“Law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice,” King writes. If African Americans are not allowed to demonstrate nonviolently, they will eventually choose violence. Civil disobedience isn’t disrespectful of the rule of law, he explains. It’s not an evasion. It shows “the highest respect for law” as an idea, and simply draws attention to laws that are unjust.

He’s also heard enough calls for patience from people who already live comfortable lives. “For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’” he writes. “It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never.’”

King explains to the clergymen—and to their wider audience—facts about African American history that are widely taught today but which were left out of history books at the time: The condition of black America is directly connected to 340 years (at the time) of slavery and servitude, including laws designed specifically to hold back African Americans. In many slave states, for example, it was a crime to teach slaves to read and write. Slave owners were afraid that education was a step toward freedom.

To the claim that the protesters are responsible for the violence inflicted on them, King asks if the man holding money should be blamed for inciting someone to rob him.

He rejects their comments about his being an “outsider.” He has a right to fight injustice in Birmingham or anywhere else in the country. More than that, he has a responsibility, one that goes back to the first Christian missionaries, and that they also share. He defiantly tells the clergymen that they’re wrong for not joining him: “[T]he judgment of God is upon the church as never before…. Is organized religion too inextricably bound to the status quo to save our nation and the world?…I am thankful to God that some noble souls from the ranks of organized religion have broken loose from the paralyzing chains of conformity and joined us as active partners in the struggle for freedom…. I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour.”

He’s also “profoundly” troubled that the clergymen credit the police with preventing violence rather than creating it. “You warmly commended the Birmingham police force for keeping ‘order’ and ‘preventing violence,’” he writes. “I doubt that you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its dogs sinking their teeth into unarmed, nonviolent Negroes.”

The clergymen have it exactly wrong, he tells them. “I wish,” he continues, “you had commended the Negro sit-inners and demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer, and their amazing discipline in the midst of great provocation.”

King writes the final sentence and slips the papers into his lawyer’s briefcase. The seven-thousand-word letter will first be published as a pamphlet, then will appear in a several national magazines. A million copies will be circulated in churches. It will become a chapter in King’s book, Why We Can’t Wait.

Having made his point forcefully, King will accept release from jail so he can continue organizing protests. Project C will continue for almost another month. Children will join the protests, and the country will be shocked by images of them attacked by police dogs and blasted with a high-pressure fire hose. The disgust of the world will then force the city to negotiate with the protesters and give them the rights they should have already enjoyed. It will also force the federal government to increase its support for the protesters. The Supreme Court will declare Birmingham’s segregation laws unconstitutional, and shortly afterward President Kennedy will call for Congress to pass a strong civil rights law. In support of this legislation, King and his colleagues will plan the greatest nonviolent demonstration the country has ever seen. The time for waiting is long past.