It has been a roller coaster of a year for King, and this moment is no different.

Right now, he’s heading toward a pinnacle: the exhilaration that comes with winning the most prestigious honor on earth, the Nobel Peace Prize, which he’ll be awarded this evening at a ceremony in Oslo. At just thirty-five years old, he’ll be the youngest person ever to receive it.

But King knows that a stomach-churning drop is soon to follow: He has learned that J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, is determined to ruin King’s reputation and end his role in the civil rights movement. King made some legitimate criticisms of the FBI, which had not vigorously pursued the segregationists and white supremacists behind some of the violence against African Americans. Hoover, who has been distrustful of King for almost a decade and has ordered many investigations of him, several of them illegal, held a rare and bizarre press conference in which he brushed aside King’s claims by calling King “the most notorious liar in the country.” Privately, Hoover has threatened worse. William Sullivan, the head of the FBI’s spying operations, wrote to Hoover two days after the March on Washington that “We must mark [King] now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security….” More recently—about three weeks before this day of the prize ceremony—Sullivan took an astonishing step. He wrote and typed, on an untraceable typewriter, an anonymous threatening letter to King that was meant to sound as if it came from an angry African American:

King,

In view of your low grade…I will not dignify your name with either a Mr. or a Reverend or a Dr. And, your last name calls to mind only the type of king such as King Henry the VIII….

King, look into your heart. You know you are a complete my fraud and great liability to all of us Negroes. White people in this country have enough frauds of their own but I am sure they don’t have one at this time that is anywhere near your equal. You are no clergyman and you know it. I repeat you are a colossal fraud and an evil, vicious one at that. You could not believe in God…Clearly you don’t believe in any personal moral principles.

King, like all frauds, your end is approaching. You could have been our greatest leader. You, even at an early age have turned out to be not a leader but a dissolute, abnormal moral imbecile. We will now have to depend on our older leaders like Wilkins[,] a man of character[,] and thank God we have others like him. But you are done. Your “honorary” degrees, your Nobel Prize (what a grim farce) and other awards will not save you. King, I repeat, you are done.

No person can overcome facts, not even a fraud like yourself…I repeat—no person can argue successfully against facts. You are finished…. Satan could not do more. What incredible evilness…. King you are done.

The American public, the church organizations that have been helping—Protestant, Catholic and Jews will know you for what you are—an evil, abnormal beast. So will others who have backed you. You are done.

King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is. You have just 34 days in which to do (this exact number has been selected for a specific reason, it has definite practical significant [sic].) You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal fraudulent self is bared to the nation.

Along with the letter Sullivan will send an audio-tape the FBI had made by planting spy microphones in King’s hotel rooms. On the tape are recordings of King with women other than his wife, Coretta. The FBI believes this threat will lead King to commit suicide. It’s a bizarre, absurd, and shameful effort by a powerful government agency that should have been protecting the protest movement instead of trying to undermine it with childish tricks.

Adding to the tension of this day in Oslo, King is unable to turn to the man he usually relies upon for support. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy of the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, his close colleague since the days of the first bus boycott, is resentful that King is being singled out for the Nobel Prize. Here in Oslo, Abernathy’s behavior has been petulant.

On this day of international recognition and honor, King is feeling very much alone.

UNEASY LIES THE HEAD

This dark mood has been a long time coming. The assassination of President Kennedy, just over a year ago, was a stunning blow. King had seen Kennedy grow from a cautious politician, reluctant to upset Southern whites, to a champion of the civil rights movement. Then suddenly Kennedy was gone. Every American felt something; but few could understand what it meant to be at risk of assassination every day. King could. “This,” he said to Coretta, “is what is going to happen to me.”

The family of the slain president did not invite King to the funeral. He went to Washington anyway and stood anonymously on the sidewalk as the funeral procession rolled slowly by. The idea of his premature death—of assassination—had begun to take hold.

As a result, he pushed himself to work harder and accomplish more. His first concern was the civil rights bill that Kennedy had proposed to Congress. He wondered whether the new president, Lyndon Johnson, would support it or allow it to die. As a legislator, Johnson had voted against civil rights legislation. But in a meeting at the White House, Johnson assured him that “John Kennedy’s dream of equality [had] not died with him,” and swore to use “every ounce of strength I [possess] to gain justice for the black American.”

King hoped that was true. It wasn’t something anyone expected from Johnson, who had the reputation of a being pragmatic, deal-making politician, not a man driven by a cause.

King and his SCLC colleagues immediately looked for another segregated city where they might repeat the integration success of Birmingham. They wanted to keep up the pressure on Johnson and Congress. They chose St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest city in America, which was preparing to celebrate its four-hundredth anniversary. Much of St. Augustine’s economy depended on tourism, which meant the city government would be sensitive to bad publicity. That would be good for the protesters.

What they didn’t count on was the city’s lack of control over the local Ku Klux Klan. The Klan was free, as one of its members put it, to commit violence “anytime, anyplace, anywhere.” On one particularly horrific night of the protest, a mob of eight hundred whites assaulted marchers with trash cans, park benches, tire tools, and chains. The Klan also threatened business owners with violence if they agreed to the SCLC’s demands. But the ferocity of white violence in St. Augustine helped convince Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act.

GLORY DAYS

King was in a hospital, being treated for exhaustion caused by his nonstop schedule, when he learned about the Nobel Prize. He was both ecstatic and humbled. He had always felt some guilt about the attention he received. He had grown up in a privileged home with a fine education and material comfort. He had never suffered in the way that millions of others in the civil rights movement had done. To underscore the idea that the award did not belong to him personally, he donated all of the $54,000 prize money to the SCLC and other civil rights organizations, despite Coretta’s request that he set aside some of it for their children’s education.

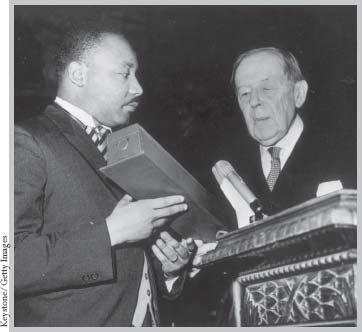

Now, this evening in Oslo, wearing the traditional striped trousers and gray tailcoat worn at the Nobel Prize ceremony, King accepts the gold medallion on behalf of the entire civil rights movement. He explains the award as recognition for the method of nonviolence, “a powerful moral force” and the “answer to the crucial political and moral questions of our time—the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression.”

King receives the Nobel Prize for Peace from Gunnar Jahn, president of the Nobel Prize Committee.

“DO THE RIGHT THING”

After his triumphant trip to Oslo, King will be invited to meet with President Johnson. They will discuss a voting rights bill, which King will argue is crucial if blacks are ever to achieve real equality in the South. Johnson tells King it will be difficult to pass a bill so soon after the Civil Rights Act. However, he’ll slyly encourage King to use nonviolent demonstrations to spur government action. “Now, Dr. King,” he will say, “you go out there and make it possible for me to do the right thing.”

King will accept that presidential challenge and wage what will, unfortunately, turn out to be his last great campaign.