“Black power!”

King winces as he hears the shout from Stokely Carmichael, the new chairman of the SNCC. Carmichael, just a few days away from his twenty-fifth birthday, is speaking to a crowd of maybe fifteen thousand people near the state capitol building. For almost three weeks King and Carmichael, along with several other civil rights leaders and many thousand supporters, have been marching through Mississippi. Though they are marching together, Carmichael has challenged King’s belief in an integrated society—what King reverently calls a “beloved community.” Carmichael believes that African Americans must self-segregate to survive and thrive. He believes African Americans will gain full constitutional rights only by taking power from the white establishment, either by force or the threat of it. King, who is thirty-seven, is considered out of date by Carmichael and other young protesters.

Integration versus self-segregation. Force versus nonviolent action. These philosophical debates go back to ancient times. Carmichael is not the first in the African American civil rights movement to express his views. They’re close to the ideas expressed by Malcolm X, and they arose even earlier: In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many African Americans took steps to move to Africa as a way of separating themselves from the white establishment in America.

Neither side can claim to be right in every case. Nonviolent noncooperation worked in India to remove British rule; but just a few years earlier it had failed to stop anti-Jewish laws in Nazi Germany. Assimilation (cultural integration) hadn’t worked for German Jews, either. They hadn’t been truly accepted—just as Carmichael believes African Americans will never be truly accepted by white Americans.

However, King could argue that real progress is being made by nonviolent direction, helped along by many white Americans who detest Jim Crow and segregation and racism.

MALCOLM X WAS ASSASSINATED IN FEBRUARY 1965 BY MEMBERS OF HIS FORMER RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATION, THE NATION OF ISLAM.

It’s probably more accurate to say that each side in the debate makes the other possible. For the civil rights movement to be successful, a lot of minds have to be changed in white America. A single argument won’t work on everyone.

King knows this. What worries him is the balance of opinion within the movement. John Lewis, the previous chairman of the SNCC, shared King’s ideals, even when he expressed impatience with King’s negotiations with leaders in Washington. But he was moved aside for Carmichael by people who weren’t as committed to integration and cooperation and nonviolence. Carmichael’s backers preferred an exclusively African American effort to take power.

ONE-MAN BAND

Despite their differences, on this day King and Carmichael are here to support and celebrate a lone protester who seems to embody the conflicting philosophies within the movement.

The man at the center of today’s demonstration is James Meredith. The march through Mississippi began as his idea. More than that, it began as a one-man march.

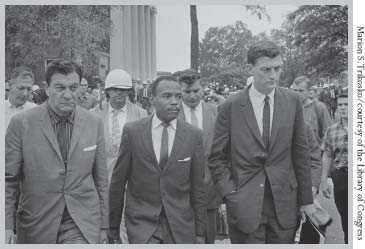

Meredith had already earned prominence in the civil rights movement with his efforts to attend the University of Mississippi in 1961. After a legal battle that lasted eighteen months, the court had ordered the university to admit Meredith, but it took more than one hundred U.S. marshals and a bloody, night-long riot before he was quietly registered. In 1963 Meredith became the first African American to graduate from the university.

Meredith’s latest effort, the march from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, began three weeks before this day. It was meant to encourage blacks to register to vote. But just two days into his march, a man named Aubrey James Norvell, hiding in the brush along the march route, ambushed Meredith and blasted him with a shotgun. Fortunately, Meredith wasn’t critically wounded. But he’s still confined to a hospital bed.

King, Carmichael, and other leaders of the movement have all visited Meredith in the hospital to offer their support. They want to stage a mass protest.

Meredith rejects this idea and insists he just wants to continue his march. Out of respect, the civil rights leaders agree. During the meeting King notices that Meredith veers more to Carmichael’s philosophy than King’s. That will soon become even more evident.

James Meredith walks to class at the University of Mississippi in 1962, accompanied by federal marshals, some of them in helmets.

“WE SHALL OVERRUN”

Unlike King, who has always approached the civil rights movement as a Christian ministry, Carmichael comes to it as a student of politics. After graduating from the competitive Bronx High School of Science in New York City, one of the very best schools in the country, he attended Howard University in Washington, D.C., and graduated with a degree in philosophy. He was greatly influenced by academics who combined careful study of colonialism in Africa with a call for the overthrow of the European colonial powers there. The success of many independence movements in sub-Saharan Africa in the early 1960s seemed to Carmichael to prove the value of using force to back up a demand for rights.

The model of colonial Africa also influenced Carmichael’s attitude toward white Americans who were working for SNCC. Carmichael didn’t believe whites should be allowed in the group. This was a great difference between him and the man he replaced, John Lewis, as well as between him and King.

Soon after King and Carmichael and the others restarted Meredith’s march, King noticed that many of the marchers shared Carmichael’s views. “This should be an all-black march,” he later remembered hearing. “We don’t need any more white phonies and liberals invading our movement. This is our march.”

When the marchers sang “We Shall Overcome,” some refused to sing the words “black and white together.” Instead of the words “We shall overcome,” they sang, “We shall overrun.” As Carmichael explains to King, “Power is the only thing respected in this world, and we must get it at any cost.”

Ten days before this protest in Jackson, when the march was in the town of Greenwood, Carmichael had first used the phrase “black power” to rally the marchers. He’d been arrested earlier that day on a made-up charge of “trespassing,” and was released with barely enough time to make it to that evening’s demonstration. “Every courthouse in Mississippi should be burnt down tomorrow,” he told the crowd. “We want black power!” he called out. The audience response came back: “We want black power!”

King thought the phrase was too confrontational. Carmichael and others thought it was just confrontational enough. Meanwhile the marchers were reaching towns even worse than Greenwood. In Philadelphia, Mississippi, where two years earlier three civil rights workers had been murdered, a mob of three hundred whites followed the marchers and threatened them.

“I believe in my heart that the murderers are somewhere around me at this moment,” King announced during a memorial service for the murder victims. Chief Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price, standing a few steps behind him, said in a stage whisper King could hear, “You’re damn right, they’re right behind you now.”

A few days later, when the march was in Yazoo City, organizers learned that back in Philadelphia the town’s black residents had been attacked. “In Mississippi murder is a popular pastime,” King told the crowd. But they should not give in to the natural urge for revenge, or even the calls for self-segregation: “We are ten percent of the population of this nation and it would be foolish for me to stand up and tell you we are going to get our freedom by ourselves,” he says. What’s necessary, he declares, is for every white American to realize “that segregation denigrates him as much as it does the Negro.”

That night the strain he felt was obvious. “I’m sick and tired of violence,” he told the crowd. “I’m tired of shooting. I’m tired of hatred. I’m tired of selfishness. I’m tired of evil. I’m not going to use violence, no matter who says it.”

THE DESCENDING SPIRAL

Now, a few days later, the march has reached Jackson, its destination, for a mass rally. James Meredith has rejoined it. He’s as independent as ever—yesterday morning he set out alone to finish the march the way he began it. And some of the march organizers had to quickly follow after him so reporters wouldn’t think he was abandoning the mass protest. It took most of the day for him to be convinced to finish the march with everyone else.

This morning, Meredith is firmly on the side of Carmichael and those in the crowd calling for black power. He shakes a walking stick at some of the speakers who offer a softer message.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” King said to one reporter. “The government has got to give me some victories if I’m going to keep people nonviolent. I know I’m going to stay nonviolent no matter what happens, but a lot of people are getting hurt and bitter, and they can’t see it that way anymore.”

Later King would described his objection to violence this way: “The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral, begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you may murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate. So it goes…. Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

But the mood of the civil rights movement is swinging like a pendulum away from King’s beliefs. When James Meredith called his protest the “March Against Fear,” he was referring to the fear African Americans felt living in a country where they were denied rights at the most basic protection of the law. King feels a different kind of fear. He is afraid the divisions within the movement will weaken it; he is afraid that African American anger, despite being legitimate, will be expressed in violence that will slow the cause of civil rights or possibly reverse the progress that has been made; and he is afraid that his vision of an integrated society, a “beloved community,” will be impossible to realize.