A tremendous rainstorm is battering Memphis, and tornado warnings have been issued. King, exhausted from constant traveling, doesn’t want to leave his motel. Ralph Abernathy insists King must keep his word to speak to a rally of city sanitation workers. The workers, nearly all of them black, are on strike for better salaries and working conditions following the recent deaths of two of their members in a storm like this one.

King fears the threatening weather will keep the crowd small, and reporters will then blame him personally, calling it a sign that his philosophy of nonviolence is no longer important within the civil rights movement. This negative thinking has become a reflex in the past year. King has become more depressed by the divisions within the movement; by certain people within it who seem to have selfish motives; by the difficulties of integrating the movement so it includes other people of color; and, most important by far, by the arguments that nonviolence isn’t working well enough or quickly enough.

King has become a victim of his own success. He always wanted a large community of intelligent, passionate members who would choose the movement’s course together. He has that now; and with it he has many colleagues who disagree with him and with each other. He also has people who have joined the movement because its record of successes gives them a chance to fulfill personal ambitions. These unfortunate developments are common when organizations grow, whether in politics or business or even schools. But rather than observe the tensions from a distance, King feels responsible for what he perceives to be the failings of the group.

King has become isolated from his colleagues and his friends. To some extent, that isolation is self-imposed. Unwilling to accept anything other than the philosophy of nonviolent noncooperation that is so important to him, he’s withdrawing himself from the movement. But that isolation also comes from being pushed away from colleagues and contacts with whom he once worked closely.

As soon as he became successful in getting the politicians like President Kennedy and President Johnson to listen to the movement’s concern, and began to negotiate with them the way forward, he was criticized within the movement by some colleagues who felt he gave away too much. Meanwhile, politicians have grown frustrated that the movement keeps making demands, and that it doesn’t act in the predictable manner they’d like. In acting as a diplomat, he has absorbed the hard feelings each side feels for the other.

President Johnson is angry at King for a more specific, concrete reason. King has dared to criticize the growing American military involvement in Vietnam. It will be years before the majority of Americans see the problems King sees with that war. Even some of his colleagues see the issue as minor compared to civil rights. But, as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, King feels compelled to speak out against a war he believes is morally wrong. “I am mandated by this calling above every other duty,” he said, “to seek peace among men and do it even in the face of hysteria and scorn.”

But of course King’s friends and colleagues have not rejected him personally. They’re distressed by the changes in his mood. Worst are the many comments he makes about being assassinated. He refers to this possibility—in his opinion, this inevitability—more and more often. Everyone who works with him knows this risk has always been real, but they also feel King is becoming fixated on the idea, beyond reality.

On this day, they’re wrong. A block away from King’s room at the Lorraine Motel, an escaped convict named James Earl Ray pays for a room at a boarding house. In his luggage is a high-powered rifle.

THE POOR PEOPLE’S CAMPAIGN

King wonders why he’s in Memphis in the first place. While the sanitation workers’ strike is important, King isn’t one of the organizers. His SCLC is trying to put together a large protest in Washington, D.C., and he needs to give that effort his full attention.

King has begun to consider the issues surrounding oppressed people in global terms. He conceived his next great campaign as a movement to end poverty not just for blacks, but for Hispanics, Native Americans, and even impoverished whites.

The Poor People’s Campaign, as he called it, would begin with a massive demonstration in Washington. It would be designed to disrupt the nation’s capital and convince Congress to pass an Economic Bill of Rights that would guarantee a job for everyone able to work and an annual income for everyone who couldn’t.

A government commission had studied just such a plan, one that would have included decent housing for the poor. The price tag: $32 billion—the cost of waging war in Vietnam for one year. President Johnson, who once hoped to make the elimination of poverty his administration’s grandest achievement, rejected the plan as too expensive.

The Poor People’s Campaign promised to be the most ambitious, most complicated, and costliest operation ever undertaken by King and the SCLC. Many of his associates thought it too big. They worried whether the participants could be trusted to remain nonviolent. They were having trouble finding grass-roots supporters who would commit to it. King needs all of his energies and persuasive powers to convince them it’s the right thing to do.

What has happened so far in Memphis hasn’t helped. A few weeks earlier, after a successful speech, King agreed to return to Memphis to lead a protest march. The march was a disaster. The SCLC made none of the usual preparations, instructed no one in the nonviolent philosophy. As King led the way, a number of marchers behind him began breaking store windows and looting. King’s colleagues, seeing the march dissolve into a riot, whisked him away to a nearby hotel.

King was in despair. He expected news reporters to criticize the violence, and to question whether the same would occur in Washington if the Poor People’s Campaign took place. “Nonviolence as a concept,” he told his associates, “is now on trial.”

“I MAY NOT GET THERE”

After arguing with Abernathy about appearing at this evening’s rally, King finally gives in and rides to its site, the Masonic Temple, through the wind and rain. Once there, he delivers a powerful message, saluting the sanitation workers in their struggle against poverty. Then he offers a prophetic confession of the fears that are consuming him: “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And he’s allowed me to go to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will to get to the promised land.” He collapses into Abernathy’s arms, spent but elated at the thunderous ovation.

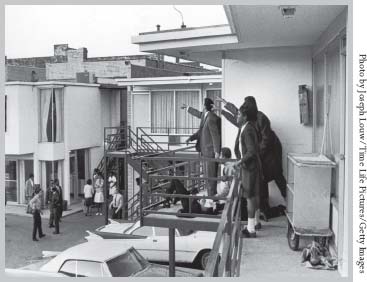

It is hours before he finds his way back to the Lorraine Motel and sleeps. The next day will be his last. When he steps onto the motel balcony to chat with associates in the courtyard below, James Earl Ray will fire a single shot that strikes King in the neck. King will be rushed to a hospital, but will be declared dead one hour later.

Ray will escape at first, traveling as far as Canada and then London, but two months later the FBI will catch him, and, except for a three-day escape, he will spend the rest of his life in prison.

King’s assassination will unleash a torrent of grief and rage. Riots will explode in 110 American cities. In Washington alone, 711 fires will be set ablaze, and ten people will die. The New York Times will call King’s murder “a national disaster, depriving Negroes and whites of a leader of integrity, vision and restraint.” The Times of London will say that King’s death is “a loss to the whole world.”

Within two weeks, the mayor of Memphis will come to an agreement with the sanitation workers, and Congress will pass the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which bars discrimination in housing.

April 4, 1968: Moments after King collapses, others on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel point in the direction of the gunfire so people in the courtyard below can find the assassin.

At his funeral procession, King’s coffin will be transported on a farm cart pulled by two mules, symbolizing King’s last unfinished dream, the Poor People’s Campaign. The monument on his grave will bear a slightly amended version of the closing from his famous speech in Washington: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty I am free at last!”!