In which I seek to rid you of any residual optimism that federal power can be rolled back through the normal political process.

AT THIS POINT I need to respond to a position you might reasonably hold. It goes something like this:

Murray is giving up on the political process too soon. He’s admitted that some court-ordered reforms have improved the legal system in recent years. Constitutional jurisprudence can get better as well—the Supreme Court has handed down some good decisions over the last twenty years, and would have handed down many more if the Court had included just one more Madisonian justice. The bad effects of over-regulation are more widely recognized than ever before, among moderate Democrats as well as Republicans. And Murray is too hard on the Republicans. The new GOP majority after the 1994 election did many good things in the first few years, and there’s no telling what the GOP House and Senate majorities in the early 2000s could have accomplished if George W. Bush had shared Ronald Reagan’s mindset.[1] In any case, the things Murray complains about in the early 2000s were anomalous. The Republican majorities elected in the fall of 2014 will behave better. If we continue to do our best to convey our strong case to the American people and win some elections, we can still make a lot of progress through the political system.

In one respect, I don’t disagree. To reiterate what I wrote in the prologue, Madisonians have successfully used the political process to win important policy victories. We should continue those efforts to improve federal policy in welfare, health, education, criminal justice, and the many other domains in which improvements are feasible and badly needed. But this book is not about policy improvements. Rather, I am asking how we can roll back the reach of federal power, something that cannot be done through the normal political process. Let me offer a final pair of reasons for that pessimistic conclusion: the nature of institutional sclerosis in advanced democracies, and the nature of electorates in advanced democracies.

The narratives in the preceding four chapters were specific to America’s particular history. No other country has ever had the chance to abandon a constitution mandating limited government, as we did. Other advanced countries have avoided many of the lawless features of the American legal system. Our separation of the executive and legislative branches makes our brand of systemic corruption quite different from the types of corruption that have evolved in parliamentary democracies. But in one respect, America is experiencing something that has happened in all the advanced democracies, whether in western Europe, Scandinavia, or Japan. No matter what their initial political or economic systems may have been, the institutions of successful nations eventually become sclerotic.

In 1965, economist Mancur Olson published a seminal book titled The Logic of Collective Action. In it, Olson set out the ways in which collective action in a democracy differs in groups of different sizes. Seventeen years later, Olson followed up with The Rise and Decline of Nations, in which he applied the argument of The Logic of Collective Action on a grand scale.

Both books are technical and closely reasoned. I restrict myself to just two of Olson’s many important conclusions. First, advanced democracies inherently permit small interest groups to obtain government benefits for themselves that are extremely difficult for the rest of the polity to get rid of. Second, these successful special interests inevitably pile up over the years until the political system becomes rigid and unresponsive, unable to adapt—the dictionary definition of sclerotic.

I will use two thought experiments to illustrate the binds that Olson identified.

Why It’s So Hard to End Government Programs That Benefit Only a Few People

The first thought experiment speaks to a question that many Madisonians frequently mutter to themselves: Why is it so incredibly hard to get rid of any government program, no matter how small, no matter how unneeded, no matter how outdated? It’s understandable that Congress doesn’t have the intestinal fortitude to buck huge special interests like the teachers’ unions or the oil industry, but why can’t it at least lop off the profusion of small, useless programs that litter the federal landscape? The answer lies in the asymmetry of motivation between the few who benefit and the many who pay for that benefit.

Imagine a nation of 100 million coffee drinkers in which 1,000 farmers grow coffee. The country is ruled by a dictator. The coffee farmers pay him an annual $10 million bribe to restrict coffee imports so that the 1,000 coffee farmers can charge twice the world market price for coffee. The bribe is financed by a $10,000 annual contribution to the bribe fund from each coffee farmer. But the import restrictions mean that the average coffee farmer makes an extra $200,000 per year, and anyone who tries to be a free rider comes under intense pressure from the other 999 coffee farmers. So the coffee farmers have no problem maintaining 100 percent participation in their organization.

A public-spirited citizen figures out that people who aren’t coffee farmers could collectively save billions of dollars a year if they were paying the world market price for coffee, so he sets out to organize an even bigger bribe to get rid of the import restrictions. In principle, it’s an easy win. Suppose, for example, that everyone who didn’t grow coffee contributed just $1 to the bribe fund. That would amount to a bribe of $99,999,000. The coffee farmers couldn’t possibly match that.

But hard as the public-spirited citizen tries, he can’t get his crusade off the ground. The vast majority of coffee-drinkers just don’t care enough about the price of coffee to get involved. The small minority who would be willing to contribute stop when they see that almost all of their fellow countrymen want to be free riders. And so for decade after decade, 99.999 percent of the citizens pay twice the world market price for coffee to benefit 0.001 percent of the citizens.

It’s not really a thought experiment, of course, if you substitute “sugar” for “coffee.” For decades, the federal government has artificially boosted the price of sugar at the behest of a small number of sugar farmers and caused Americans to pay about twice the world market price. The sugar subsidy has survived repeated attempts to end it, most recently in 2013.2 The reason it cannot be ended is precisely the one that Olson describes: when government favors are up for sale, the comparatively small number of people who benefit are willing to pay a price to acquire and maintain those favors that is far greater than the price the rest of the nation is willing to pay to get rid of them.

Why It’s Impossible to Contain the Demand for Government Favors in Advanced Democracies

The second thought experiment speaks to a question that must cross the minds of most politically aware Americans across the political spectrum: What accounts for the feeding frenzy at the government trough? Why are so many Americans so selfish and cynical about profiting at the expense of their fellow citizens?

Mancur Olson has good news in this regard: selfishness and cynicism don’t necessarily have anything to do with it. The bad news is that bad motives aren’t required to keep the feeding frenzy going. Journalist Jonathan Rauch devised this second thought experiment in Government’s End, a full-length book treatment of Olson’s work as it applies to contemporary Washington.3

Four friends sit down to dinner in a restaurant, agreeing to split the bill equally. Three of the four diners order appetizers costing $8, $10, and $12. The fourth realizes that if he orders the $50 snail darter soup, his share of the cost for appetizers will be just $20. That’s a 60 percent discount. But as he tells the server what he wants, his friends first razz him and then tell him if that’s how he’s going to play the game, the deal is off. They’ll get separate checks. He orders a $10 appetizer instead—he didn’t want the snail darter soup enough to pay the full price.

Now imagine the same menu, but the dinner is in Madison Square Garden with 10,000 diners who are all strangers. Once again, the total bill will be split equally. Everybody knows that’s the rule—and so everybody disregards the prices on the menu. Everybody ends up spending $200 for dinner instead of the $50 that almost all of them would have preferred.

The 10,000 people are being rational. If one of them—Mary, let’s say—unilaterally orders a $50 meal while the other 9,999 average $200, she will lower her bill by less than two cents. If she has any preference whatsoever, however small, for the more expensive options, Mary is a fool not to get them. Furthermore, no matter how much Mary might want to reach an agreement with the other 9,999 people to behave with restraint, Mary has no way to influence more than a handful of other people around her to restrain their spending.

Mary is in the same position as any organization confronting the reality of Washington today, whether that organization is a business, a union, an advocacy group, or any other organization. We call them “special interests,” which makes them sound selfish, but seen from another perspective they are simply doing what we all see ourselves as doing, worrying about legitimate concerns. All organizations have interests that they want to protect, whether it’s the Sierra Club’s interest in preserving the wilderness or the Weyerhaeuser Corporation’s interest in being able to harvest timber. Even if we assume honesty and good faith on both sides, their interests are going to clash. If the Sierra Club is lobbying for what it sees as reasonable restrictions on logging, Weyerhaeuser cannot afford to assume that the Sierra Club’s definition of reasonable will be reasonable from Weyerhaeuser’s point of view. Weyerhaeuser needs to have its own position represented in the fight. Now imagine what happens when thousands—tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands—of parties with competing interests are involved.

The people seeking the favors “are acting not out of greed or depravity,” Rauch writes, “but out of the impulse to survive in the world as they find it. Good intentions, or at least honest intentions, breed collective ruin.” He continues:

If you see others rushing to lobby for favorable laws and regulations, you rush to do the same so as not to be left at a disadvantage. But the government can do only so much. Its resource base and management ability are limited, and its adaptability erodes with each additional benefit that interest groups lock in. In fact, the more different things it tries to do at once, the less effective it tends to become. Thus if everybody descends on Washington hunting some favorable public policy, government becomes rigid, overburdened, and incoherent. Soon its problem-solving capacity is despoiled. Everybody loses.4

The economic consequences of sclerotic institutions are huge because of another dynamic that Olson identified: It’s typically much more efficient for a special interest to try to get a larger piece of the existing pie than to seek changes that increase the size of the pie for everyone. Suppose, for example, that a corporation makes widgets. Does it spend its lobbying money to increase the size of the pie for the widget industry, or to acquire a competitive advantage for itself? The payoff of a specific advantage for a corporation is larger and more certain than changes that increase the size of the pie for everybody. Accordingly, the corporation spends its money to get a larger slice.

This aspect of Olson’s theory explains why many large corporations are quietly happy about the regulatory state. They have the political clout to shape legislation and regulations to their advantage, and also have the financial and personnel resources to cope with government requirements that overwhelm smaller competitors. The notorious Dodd-Frank bill to regulate the financial industry, excoriated by many businesspeople and economists as the worst kind of incomprehensible regulation, is a case in point. As the chairman of JPMorgan Chase observed with remarkable candor, Dodd-Frank works as a “bigger moat” to protect the large investment banks like JPMorgan Chase, deterring smaller institutions from entering their markets.5

Olson argued that each time this pie re-slicing goes on, the society as a whole systematically becomes poorer—re-slicing not only fails to increase the size of the pie; it exacts costs that shrink it. In addition, increasing institutional sclerosis cripples technological innovation. But these are ancillary to my main point: that the United States is in the grip of a process that afflicts all advanced democracies.

Why the United States Avoided Sclerosis for So Long and Why We Ultimately Succumbed

Serendipitously (the founders didn’t know about institutional sclerosis), the founders set up a system that by its nature prevents institutional sclerosis from getting out of hand. In America’s free-market economy, sclerosis was kept under control in the private sector because sclerotic corporations went out of business or were bought up by companies that were still vibrant. Meanwhile, the enumerated powers restricted the number of favors within the power of the federal government to sell. The cause of institutional sclerosis—the incremental effects of thousands of special interests protecting their benefits—was forestalled because Congress did not have the authority to grant many of the desires of special interests.

The system worked. Recall chapter 4’s discussion of corruption in Washington before the 1970s. It was garden-variety corruption, with only the beginnings of sclerosis, attested to by the extremely limited lobbying that went on before the 1970s. But the system that forestalled sclerosis had been destroyed when the Supreme Court trashed the enumerated powers. It took three decades for sclerosis to set in, but once the enumerated powers no longer restrained the goods that Congress could sell, the prognosis—steadily increasing sclerosis, eventually becoming terminal—was inevitable.

The problem with the sclerotic state is not that the wrong people get benefits conferred by government. That happens a lot, and it’s too bad. But the truly crippling and ultimately paralyzing effect of sclerosis is what it means for government’s ability to act in ways that reduce the net number of problems. Once again, Rauch states the problem well:

The question is not the quantity of activity but how effectively a given amount of activity solves problems “on net.” That phrase “on net”—meaning “on balance,” after the wins and losses are tallied up—is important. In life, every solution creates at least some new problems. The trick is always to find solutions that create fewer problems than they solve. In the classic example, if you kill a fly with a flyswatter, you come out ahead on net. If you kill a fly with a cannon, you create more problems than you solve.… Problem-solving capacity is precisely what seems to have been shrinking for the federal government.6

We are living under a political system that has tied itself in knots. “Cleaning house” in Washington will do nothing to untie those knots. The current public-policy debate concentrates on culprits such as the political polarization that is alleged to have immobilized Congress and failures of presidential leadership assigned to George W. Bush by the left or to Barack Obama by the right. Such culprits have some degree of culpability, and have made a difference at the margin. But when it comes to an explanation of why government under both Democrats and Republicans has become so pathetically ineffectual across the board, even at simple tasks, a powerful underlying explanation is that American government suffers from an advanced case of institutional sclerosis.

It is impossible for a government in the grip of the disease to cure itself. The symptoms of the disease prevent the government from acting to cure it. There’s only one surefire solution: lose a total war. That’s the insight that inspired Mancur Olson in the first place. Why, he asked himself, were the fortunes of Germany, Japan, England, and France following World War II so strikingly different? As of 1945, Germany and Japan had surrendered unconditionally. Many millions of their populations had been killed. Their factories, roads, bridges, dams, railroads, airports, water systems, power systems, and communications systems were in ruins. Almost all of their political and economic institutions had been dismantled. Meanwhile, Great Britain and France had finished the war with far lighter casualties and less damage to their physical infrastructure. Their political and economic institutions were intact.

What happened next was that Japan and Germany experienced explosive economic growth and within three decades after the war’s end were among the most prosperous countries in the world. During the same period Great Britain and France languished, with some of the slowest rates of economic growth among advanced countries.

How could countries starting from scratch so quickly catch up to and then race past advanced industrial countries that had been so far ahead in 1945? The short answer is precisely that Japan and Germany did have to start from scratch. Losing their physical infrastructure was a problem, but losing their political and administrative infrastructure was a godsend. Their enemies had unintentionally administered the one known cure for institutional sclerosis.

Couldn’t Britain and France, both democracies, have mustered the votes to modify their systems when they saw the blazing success of Germany and Japan? Can’t the United States now? No, because of the nature of the electorate in advanced democracies. All advanced democracies are welfare states, and welfare states inherently create constituencies in support of the status quo.

In chapter 3, I offered the fundamental theorem for explaining government corruption. Now let me offer the fundamental theorem of democratic politics: People who receive government benefits tend to vote for people who support those benefits. The theorem applies as much to middle-class Social Security recipients as to impoverished welfare mothers; as much to farm owners getting agricultural subsidies as to farm laborers getting Food Stamps; as much to defense contractors getting billion-dollar contracts as to nonprofits staying afloat with small government grants.

I use tend in a statistical sense. Receiving government benefits may, in the jargon of social science, explain only a small amount of the variance in voting behavior. But elections are binary events in which one vote can make the difference between victory and defeat. Small statistical tendencies drive large electoral outcomes.

For American elections from 1789 through 1932, the fundamental theorem of democratic politics was nearly irrelevant. Military veterans wanted to see their pensions maintained, federal employees wanted to see their jobs maintained, and people who held government contracts wanted to see those contracts continue. But those three groups amounted to a few percent of the population. Apart from them, the number of Americans who received cash or in-kind income transfers from the federal government was zero.

As of the election of 2012, approximately half of all Americans received such benefits.7 Let’s ignore those who received small benefits and limit the argument to those for whom the role of government support is often central to their lives: people getting welfare and Medicaid benefits, and people getting Social Security and Medicare benefits. In both cases, the benefits are large, and the loss of them would often be a personal catastrophe. The continued security of those programs is likely to be near the top of the recipients’ political calculations.

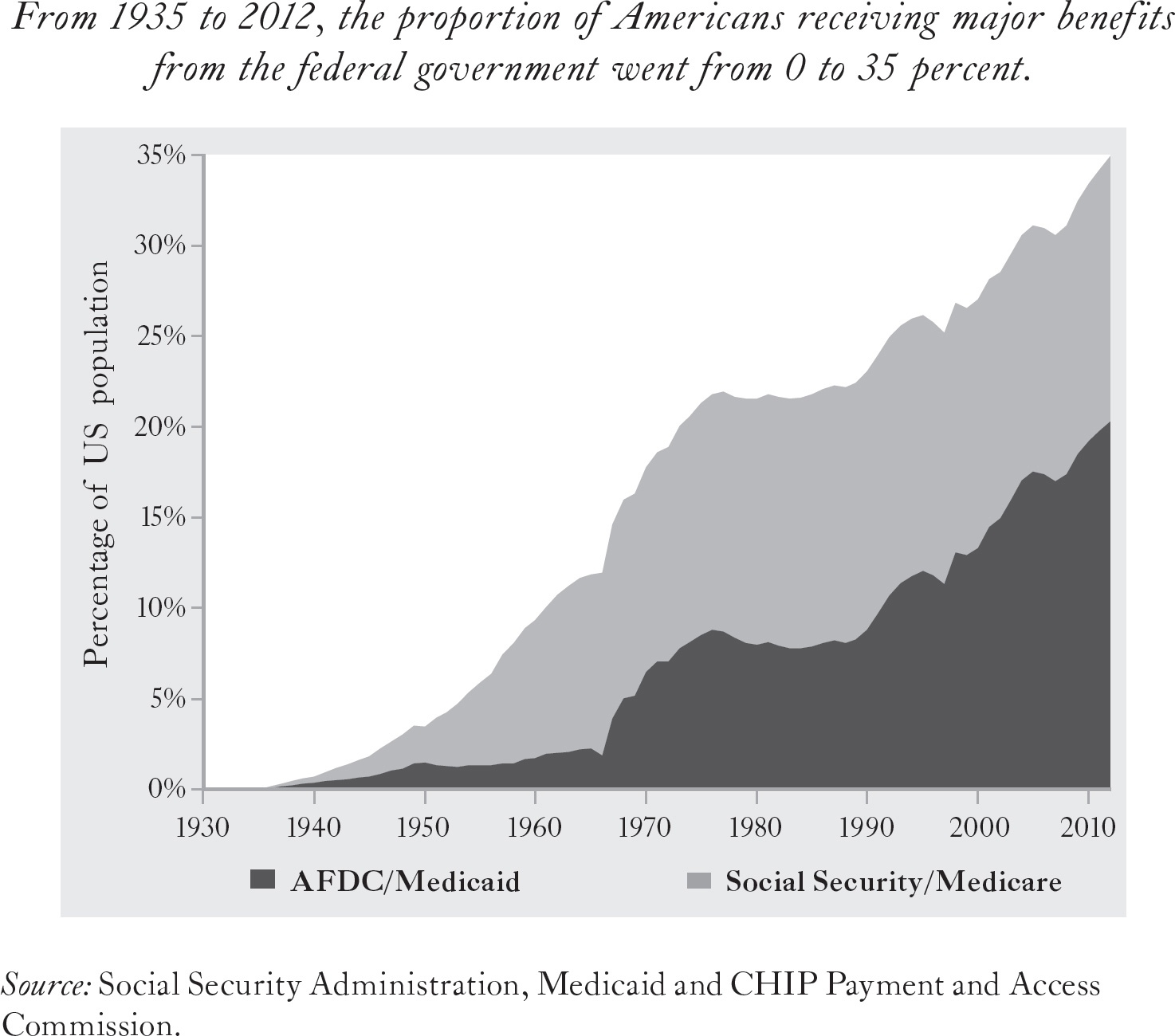

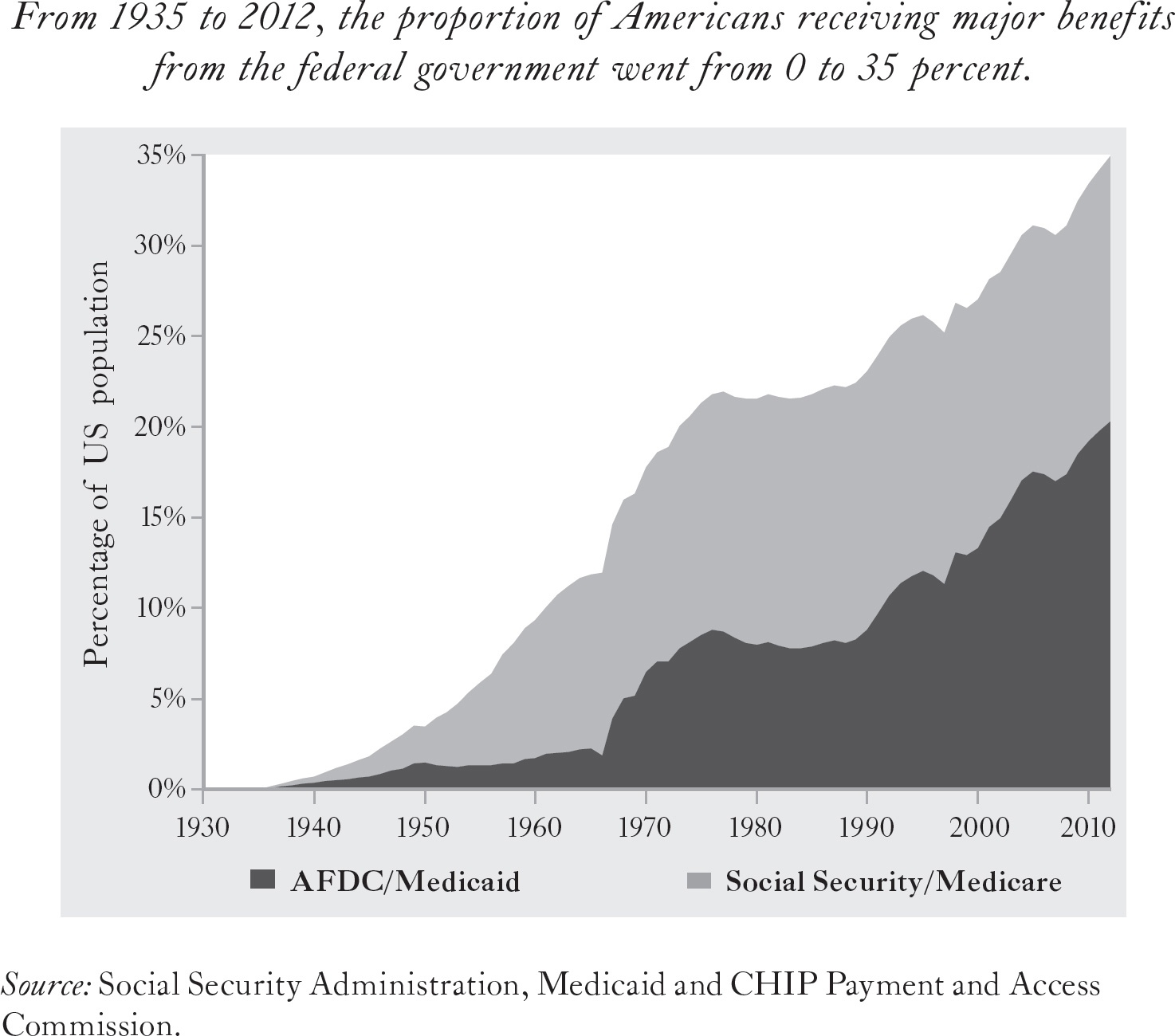

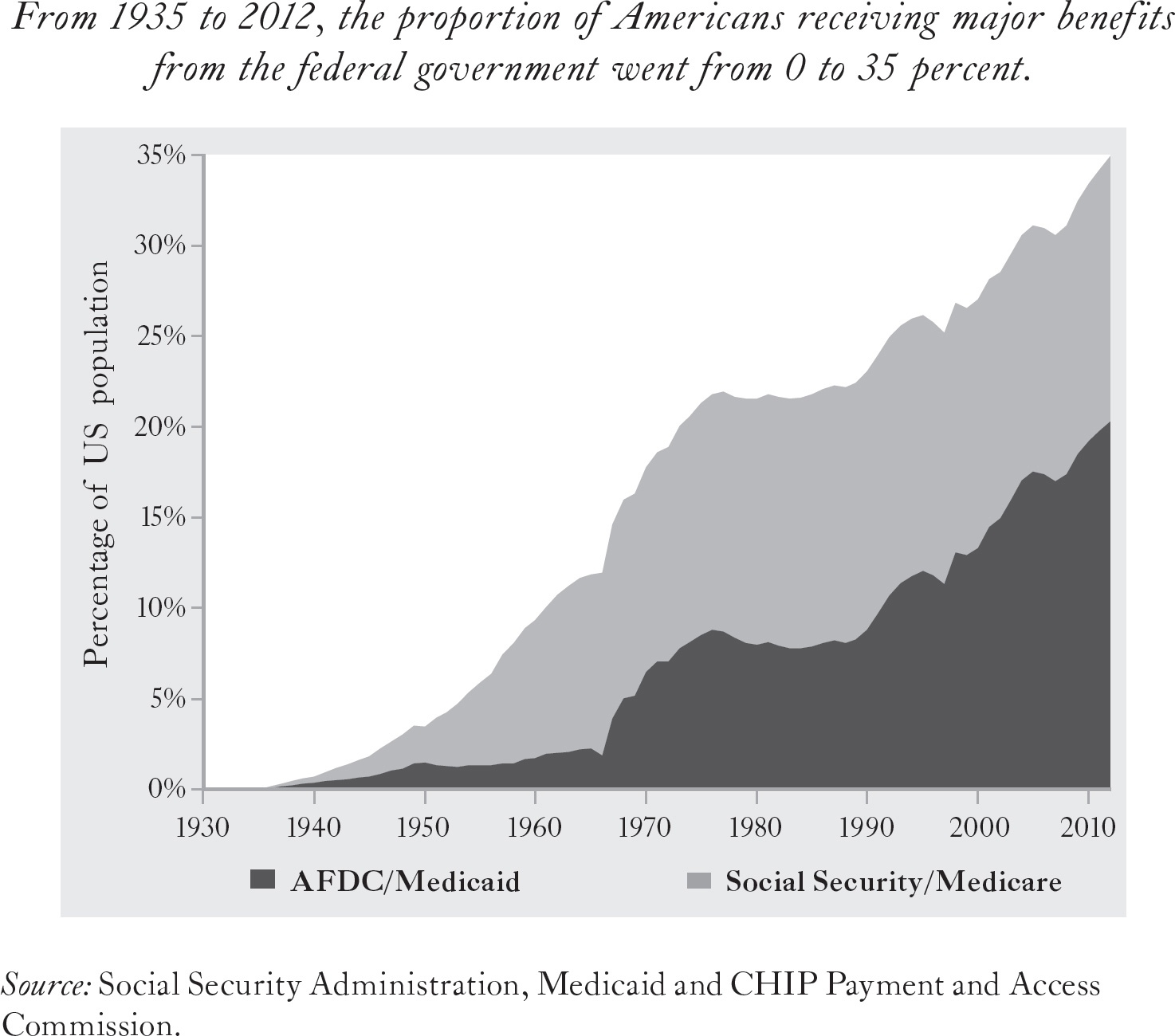

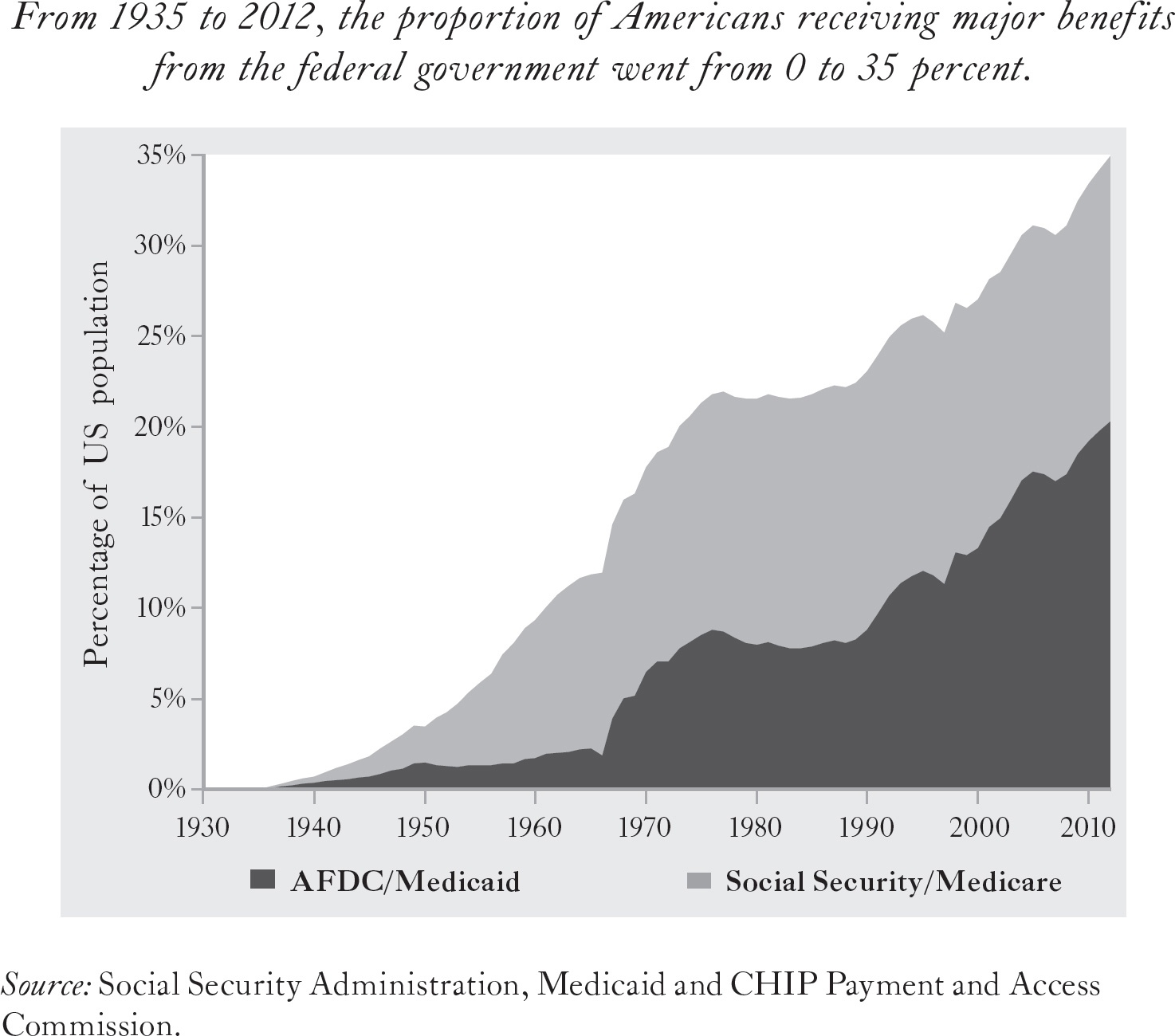

The figure below shows the percentage of the population receiving those benefits from the New Deal through Barack Obama’s first term.

When Dwight Eisenhower was elected in 1952, Medicare and Medicaid didn’t exist, and the combined number of welfare and Social Security beneficiaries amounted to only 4 percent of the population. Eight years later, when John Kennedy was elected, the percentage had more than doubled, to 9 percent of the population. By the time Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford in 1976, 22 percent of the population fell into those two groups. When Barack Obama was reelected in 2012, more than 1 out of 3 Americans was the recipient of one of those two extremely important packages of government assistance.8

Those aren’t the only people whose votes are determined in part by the role that government money plays in their lives. First, add the 22 million employees of federal, state, and local governments.9 Then add all the people who are not carried on federal payrolls but instead are working for contractors in the private sector and nonprofits receiving government grants. Nobody knows how many there are, but the federal government alone spends more than $500 billion on contracts with for-profit firms.10 Then add all the people who work for nonprofit organizations that depend on government grants for most or all of their income. Again, nobody knows how many people that amounts to, but such organizations got about $700 billion from government in 2012.11

Precise estimates of how many votes are swung because people depend on checks written by the government are impossible but also unnecessary to make my point. To illustrate: The voting group that is most intensely interested in Social Security and Medicare consists of those age fifty-five or older. In the typical presidential election, more than 40 percent of the voters come from that age group. In the typical congressional election, they approach half of the voters.12 In the General Social Survey Polls from 2000 to 2012, only 28 percent of them identified as Republicans, 18 percent identified as “conservative,” and 4 percent as “extremely conservative”—and even the votes of Republicans and conservatives can’t be counted upon when Social Security and Medicare benefits are on the table.13 Put bluntly: When more than 40 percent of people who actually cast votes have an active interest in the preservation and expansion of Social Security or Medicare, no Congress will have the votes to pass major structural reform that entails significant cuts in those benefits until fiscal catastrophe is imminent. And perhaps not even then.

The large number of beneficiaries of transfer payments further explains why principled fiscal conservatives are always a minority among Republican representatives and senators. A principled fiscal conservative may win the Republican primary, but winning the general election is nearly impossible in all except the nation’s most conservative districts. Instead, the Republicans who actually get elected are mostly fair-weather fiscal conservatives who talk a good game during the campaign, sticking to generalities, but don’t support cuts in the government benefits that are most popular with their constituents once they are in office.

What About the Growing Size of Ethnic Minority Groups?

The media and Internet are full of analyses predicting that the GOP’s future is bleak, but usually focus on the role of ethnic minorities as the cause. Blacks, Latinos, and Asians all vote Democratic by large margins, and they constitute a growing share of the electorate. They will probably constitute a majority of the population by midcentury.

These analyses are correct about the long term, but the consequences in the next few presidential election cycles will be minor, because of the much lower voter turnout among minorities than among whites. See the note for details.[14] The 35 percent of the population who are major beneficiaries of government transfers is already a potent political force regardless of the recipients’ ethnicity and will continue to gain strength independently of the growing numbers of ethnic minorities. Ethnicity does not drive the politics of a welfare state. Benefits do.

The proportion of Americans who depend on the federal government to put food on the table, whether through welfare, Social Security, a government paycheck, or a paycheck financed by a federal contract, will continue to increase, and it will push the Republican Party to the center in all presidential elections. The number of Madisonians in the Senate will always be in single digits, because only a handful of states have electorates that would conceivably elect someone committed to genuine limited government. Only the House of Representatives will continue to have an active minority of Madisonians elected by extremely conservative congressional districts, but even in the House they will be a minority of the Republican caucus.

Combine the effects of institutional sclerosis with the effects of a growing percentage of Americans who depend on the benefits provided by the welfare state, and the political landscape for Madisonians is already bleak and getting worse. A successful agenda for rolling back government through the normal political process would require Madisonian majorities in both houses and a Madisonian president. It’s not going to happen. Nothing will change that situation. It is built into the way that advanced democracies function.