Those who have tasted a summer tomato sun-sweetened on the vine or a crisp cucumber plucked from under the leaves that nourished it know the intense flavor of fresh-picked produce is unrivaled by anything found in a supermarket.

Perhaps our taste buds detect what our eyes cannot. Truly fresh produce is more nourishing and deeply satisfying to the senses. The nature of the American food system means the fruit, vegetables, and herbs found in grocery stores have often been grown hundreds of miles from our kitchens and packed, shipped, distributed, and displayed, all while being refrigerated—a process that can wreak havoc on the flavor and nutrients of delicate plants.

When food is flown or trucked to your local store, days pass between harvest and your table. Even the most perfect specimen will begin to decline before you bring it home—it loses moisture and vitamins and begins to metabolize its own reserves. Some foods, like sweet corn or snap peas, begin to transform altogether directly after picking (converting sugar to starch and losing sweetness and flavor). Although our remarkable food-distribution system provides a diverse selection of foods year-round, cost and quality are inevitably compromised.

Only a few generations ago, most of the food on the dinner table had been growing in a garden only hours before it was served. While it would be a full-time job these days to feed your family this way, it feels surprisingly good to grow some of the staples on your grocery list.

One perk of gardening is the exposure to new varieties you may not have seen or tried before. Seed catalogs and garden centers offer seemingly endless options in varying colors and shapes, often with charming historical names. Thousands of varieties of tomatoes are at your fingertips, versus the simple red, round tomato in supermarkets. A tomato grower who supplies a large market needs to grow varieties that ripen all at once for a more economical harvest that can survive shipping in good condition, while a home gardener can select tomatoes for flavor, extended harvest, and color. The same is true for many other crops.

If you buy in bulk and clip coupons for a variety of packaged foods, gardening may not cut the cost of your regular grocery bill. But if you love to buy fresh produce—especially organic—you can confidently reduce your monthly expenditures. Cost efficiency is an age-old reason to grow your own food since seeds, sun, and nature’s soil are not expensive. However, like any hobby, gardening can get pricey if you choose to purchase lots of equipment or gardening gadgets.

Backyard gardens teach children about the origin of food, creating a powerful connection to the dinner plate that’s simply magical. Kids can help plant, water, weed, and harvest produce, and after spending time caring for the plants, they’ll be more apt to eat the fruits of their labor. This same magic has an effect on adults, too. When you toss a homegrown salad together, cook a pot of greens, or serve a stir-fried medley of vegetables, you have a deeper appreciation of its amazing path to your plate.

When a family gardens, their diet is more diverse and inherently healthier, packed with vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Food in its purest, freshest form is not only the tastiest way to enjoy it but also the most beneficial nutritionally.

When you grow your own food, you know what goes into it: how it’s fertilized, what pesticides are used, and overall care. If you grow organically, you can eat organically. Not only is that beneficial for you, but also fewer chemicals and less distance traveled to get the food on your plate make for a smaller carbon footprint.

Exercise is another bonus. Anyone who says that gardening is not aerobic has never raked leaves or shoveled compost.

Keep Your Garden in Shape

• Work in moderation. Though it is easy to excitedly begin big and bold, don’t overdo it. Set achievable goals that don’t tax your muscles or your time to the point of pain. Like exercise, gardening has no finish line. One season leads to the next. The idea is to enjoy the journey and gather your rewards along the way.

• Challenge your mind and your body. If you are intellectually engaged in the garden, you’re more likely to be fulfilled by it. Each season is different. Try new varieties. Research the history on how a vegetable came to be in America today. Lay out new garden plans each year. Research a pest or problem and figure out how to deal with it. Then take comfort in the fact that you’ll never know it all. Whether it’s your first season or your fortieth, there will always be something new to grow, learn, and do.

• Adapt your garden to your life. If you have difficulty bending, plant in raised beds or containers. If you have sore joints, choose tools with large, padded handles. If there are tasks that are difficult for you, such as turning the soil or bringing home a quantity of mulch, get help, and then do the work that you can enjoy.

• Be optimistic. Try a new plant or variety each season. If a plant dies or doesn’t grow as it should this season, there’s always next year. Research, learn, and look forward to applying the lesson the next time.

• Be creative. Vegetable gardens are particularly fun because they are replanted often, sometimes three or more times each year. Think of fun ways to make a trellis for tomatoes and cucumbers, arrange your veggies in an ornamental pattern, and mix in flowers with your vegetables to use as table decorations or garnishes.

• Be social. Gardeners learn from one another. Sign up for a gardening class. Volunteer at a local botanical garden. Rent a plot in a community garden. Visit other gardeners and invite them to visit you. Get online to share and learn; many social media sites are fantastic resources for virtually visiting any garden or sharing recipes.

• Relax. Time spent weeding or doing other mindless chores is a great time to work out frustration, daydream, and problem-solve. Many gardeners find that working with their hands frees their minds.

Fruit, vegetables, and herbs almost universally require the energy of the sun to be productive, so it’s important to select a site that receives a minimum of six hours of sun each day, preferably eight hours. If your garden is close to a structure, such as your house, choose a spot on the west or south side, provided tall trees or an adjacent house or building does not shade the site in the afternoon.

Deep soil and good drainage are also crucial. If your sunny spot has compacted soil or the land is low and apt to be wet for days after a rain, consider building raised beds. The ideal size is 4 feet wide so the middle is easily reachable from both sides. Beds that are 4 x 4 or 4 x 8 feet are the most manageable; they can be built from stock lumber, work in a variety of patterns, and allow for neat and tidy configurations.

The height can range from 10 to 12 inches of mounded soil with no permanent edging to several feet tall—high enough to provide seating on the edge or easy access from a wheelchair.

The soil for a raised bed can be bagged garden soil or a mix of local topsoil and organic matter. Ask your garden center for brand or supplier recommendations. Many municipalities encourage composting by collecting organic matter and selling finished compost to residents at low or no cost—a great additive for large beds. Before filling, be sure to remove turf, loosen the soil beneath the raised bed, and amend it with organic matter so deep-rooted plants can benefit. Building and filling raised beds is heavy work in the beginning, but gardening will be easier in the long run.

Water supply is also essential. If there’s not a spigot nearby, call the plumber before you do anything else. Consider collecting rainwater runoff in rain barrels at your downspouts, too.

Soil Testing

A soil test is the smart way to assess your soil’s pH and any nutrient deficiencies. The results will help you determine what types of amendments or fertilizers are needed and how to apply them in the correct amounts. You can have your soil tested by a private lab or through a kit obtained from your local garden center or Cooperative Extension office (www.csrees.usda.gov/Extension).

Once you decide where to grow, it’s finally time to break ground. Preparing the soil is essential to success. Mark off the space for your garden using spray paint or stakes and string. If there is grass, it’s best to remove it or kill it rather than turning it into the soil—it’ll be a constant weed-producing nuisance. If the area is large, consider renting a sod cutter and transplanting the turf to another part of your property. Otherwise, cover the area with a plastic drop cloth or sheet, weigh down the edges with boards, bricks, or stones, and then wait. The heat generated by the sun will kill the lawn in two to four weeks, depending on the time of year. Take caution: Before choosing a chemical solution to kill your lawn, read the herbicide label carefully. You don’t want to apply any product not labeled for use with food crops.

For an in-ground garden: Once the grass is gone, the next step is loosening the soil. Assuming you have average topsoil that is 4 to 6 inches thick, cover the area with at least a 2-inch layer of organic material, such as homemade compost, municipal compost, rotted sawdust, bagged garden soil, aged manure, or whatever is affordable and available where you live. Turn it in using a rototiller or a garden fork, depending on the size of the plot. If you already know the garden’s layout, till just the beds and simply cover the paths with mulch to save you time and energy.

For a raised-bed garden: If you are building above the soil in raised beds, you’ll still need to remove turf. It is possible to grow atop concrete; read online to find construction plans. Prefab raised-bed kits make for easy installation.

If you don’t have much land—or your only direct sunlight falls on a paved surface such as a driveway, porch, patio, or deck—plant in containers. Select large pots or a grouping of pots in different sizes so you can grow a variety of fruit, vegetables, and herbs. You’ll be surprised how productive they can be. What you lack in surface area you make up in soil depth. Roots grow deep in a pot, while they tend to grow horizontally in a garden. Follow these tips to get the most from your container garden:

• Select a good potting soil for optimum plant growth. For best results, don’t use soil from your garden. Purchase potting soils from recognizable brands or those recommended by your local garden center. Look for a potting mix, rather than a bagged product labeled “garden soil.” Avoid those that are dense and heavy when wet. If in doubt, try small bags of different kinds. You’ll find your favorite pretty quickly, based on plant growth.

• Do not overfill your pots. Leave about an inch of the rim above the soil so that water is forced to drain down through the potting mix, rather than spilling over the edge. The soil warms quickly in a container, so gardeners may find containers helpful in getting an early start for a few plants.

• Ensure proper drainage. Use pots with drainage holes or drill sizable ones.

What’s the Right Size?

If in doubt, use a larger container than you think you’ll need. You can always add more plants later, but don’t underestimate how large these tiny seedlings can grow.

Hanging basket: strawberries, parsley, thyme

6-inch pot: lettuce, spinach, chives

8- to 12-inch pot: strawberries, beets, carrots, lettuce, radishes, spinach, chives, dill, parsley, sage, thyme

14-inch pot: arugula (3 plants), cabbage and collards (1 plant), spinach and loose-leaf lettuce (3 to 4 plants), all herbs

18-inch pot: low-bush or dwarf blueberries, strawberries, broccoli, cauliflower, large cabbage, small eggplant, all greens (in multiples), small peppers, determinate tomatoes

24-inch pot: small citrus, melons, artichokes, cucumbers, large peppers, pumpkins, summer squash, indeterminate tomatoes, cherry tomatoes, various combinations of vegetables and herbs

See our suggestions for plant combinations.

Containers are available in a variety of materials to suit your space and aesthetic. Pot feet (or any piece of brick or stone) raise a container off the surface below so as not to block the drainage hole. This also preserves surfaces like wooden decks that may rot under constant moisture.

• Terra-cotta pots are traditional and look great, but they dry quickly due to evaporation from the sides of the pot. Also, if you have freezing temperatures in your area during winter, the pots need to be stored in a dry place. The moisture that is absorbed into the terra-cotta will freeze and crack the pot.

• Glazed ceramic pots come in a variety of colors, sizes, and shapes for design-conscious gardeners. They survive mild freezes, but where the soil freezes, it may crack the pot as it expands.

• Resin or plastic pots have the advantage of being lightweight and durable. Nice ones can be costly, but they’ll last for years.

• Wooden pots or whiskey barrels are favorites of gardeners everywhere because of their generous size and rustic appearance. You can grow mixed plantings in a container this size.

• Concrete pots are an excellent choice, as long as you don’t like to rearrange your container garden very often. They can be extremely heavy, but they’re durable. It’s a good idea to place the empty pot where you want it permanently, fill it with potting mix, and then plant.

• Fiberglass pots resemble stone, wood, terra-cotta, or any material the maker wants to replicate. They’re lightweight and durable, albeit costly.

Deciding what to plant depends on the season, your site, and of course, your taste buds. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

• Cost. Growing the highest-value fruit, vegetables, and herbs can be a smart way to save on your grocery bill. Bell peppers and heirloom tomatoes, particularly if you buy organic, can be costly, so consider planting those in your summer garden. Likewise, leaf lettuce and mesclun blends can be harvested repeatedly by picking the outer, mature leaves and leaving the plant in the ground to continue growing. With any luck, you’ll be able to strike salad greens off your grocery list for half the year.

• Quality. Sometimes you can’t buy the same standard of produce that you can get from the garden. If small, tender okra is nowhere to be found in the grocery store and your growing season is long and hot enough, then grow your own.

• Convenience. If basil is an herb you love and often purchase, you may want to include it in your garden or grow it in a container so that you always have fresh leaves on hand to add to a sandwich or mix into a salad. Lettuce, cilantro, and dill all have an extended season in the spring and fall garden, but they spoil quickly in the refrigerator.

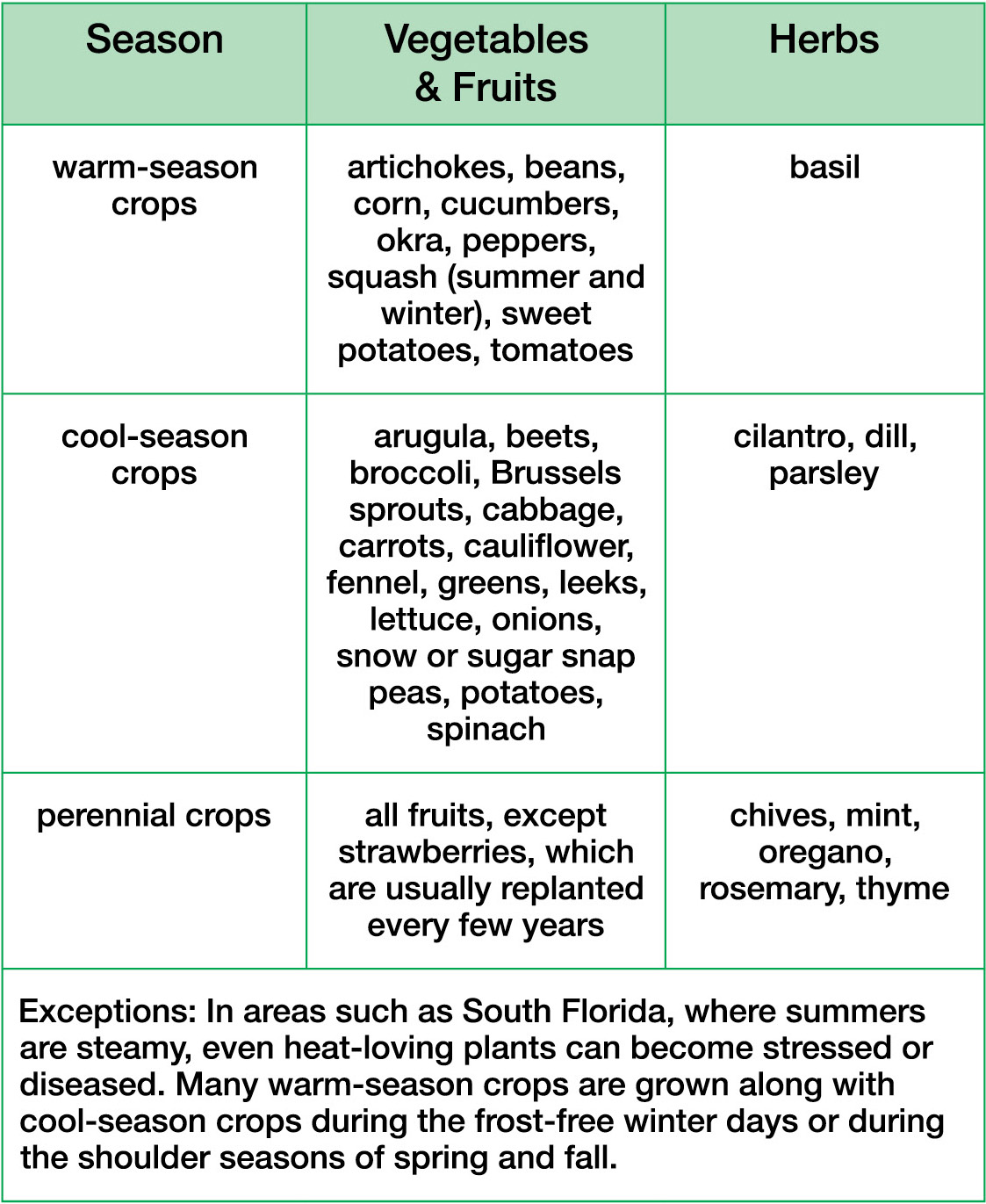

Once you know what you’d like to grow, the question is when to grow it. Most vegetables and herbs fall into one of three groups, and sometimes the group changes depending on where you live.

Frost dates for spring and fall are the most important dates on a gardener’s calendar, as they are the benchmarks for planting. Years of weather records have resulted in fairly accurate predictions of when to expect the last killing freeze in spring and the first killing frost in fall in areas around the country. Consult the chart on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website (cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/climatenormals/clim20supp1/states) to find the spring and fall dates for your area.

In addition to the plant profiles throughout this book, you’ll find planting instructions (i.e., “plant in spring two to four weeks before the last expected frost”) on seed packets and plant labels. It’s important to note that a light freeze will not kill cool-season crops. Even lettuce can withstand temperatures in the mid- to high 20s. However, warm-season plants, such as basil and squash, will show damage from the slightest 32° frost.

Most vegetables and herbs can be grown from either seeds or transplants, while most fruit mentioned in this book (except melons) must be grown from transplants.

When the season is short, vegetable and herb transplants have the advantage because you get a jump start on the growing season with a healthy, sizable plant. If you don’t have space to start your own seedlings indoors, it’s often easier and more successful to buy transplants. For beginning gardeners, it’s best to start with mostly transplants and mix in seeds as you learn.

If the season is appropriate, seeds are always a good idea. They’re simply more economical. A seed packet might produce 50 lettuce plants for the cost of one cell pack of six transplants. Some items, such as carrots or radishes, must be grown from seeds.

Availability will also dictate what you choose because your local garden center might not carry the particular variety you want to grow. You’ll need to plant seeds directly in garden soil or grow your own transplants by sowing seeds indoors in containers prior to planting outside.

Space is at a premium for many gardeners, but with careful planning you can have a fruitful garden no matter the size. Here you’ll find plans for all seasons to give you some ideas for your garden.

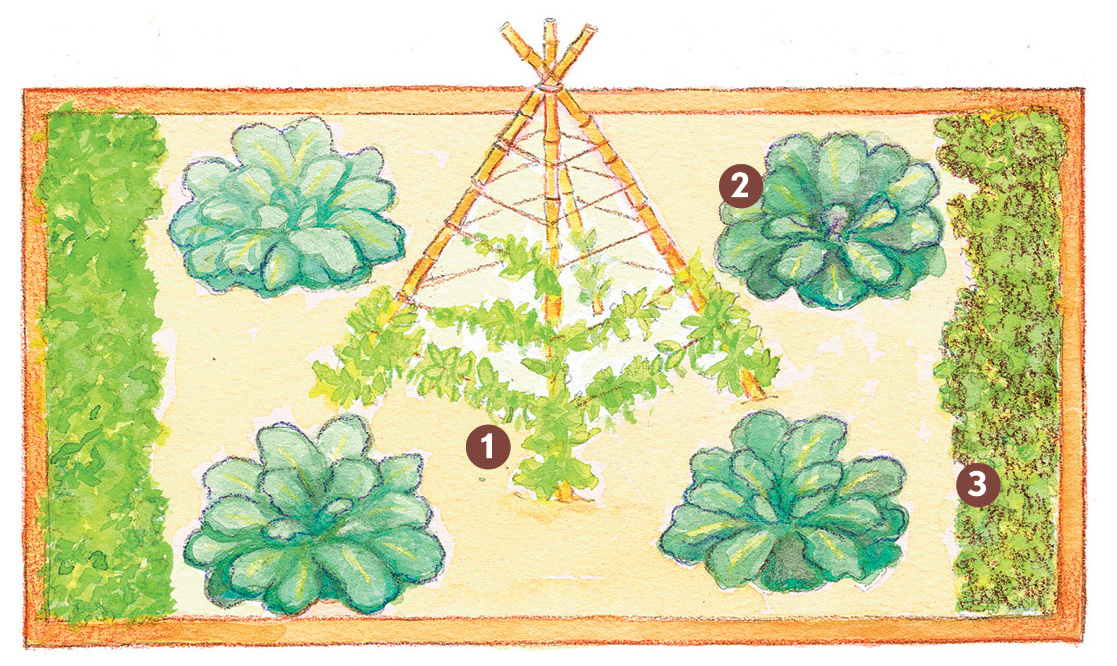

Beds The plans shared over the next few pages were designed for 4 x 8–foot beds that can take you from cool to warm season. The plant combinations are flexible and meant to serve as a guide to help you get started. Follow these specifications exactly or customize your garden to suit your taste buds by planting any of the recommended substitutes.

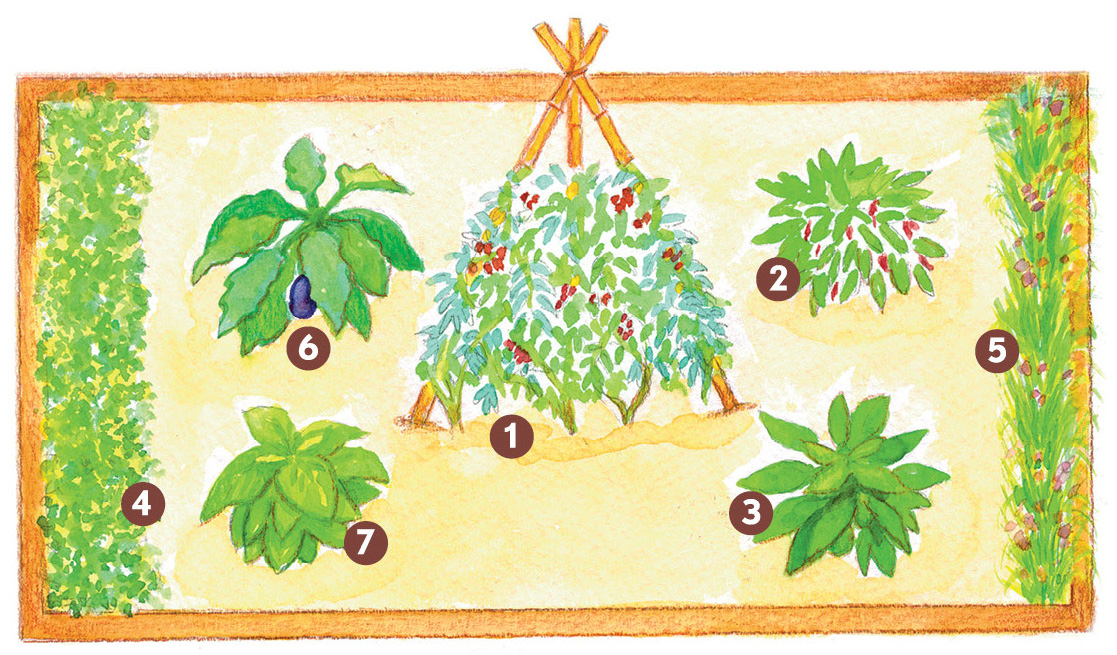

A semipermanent tepee constructed of three to four vertical stakes made of bamboo, spiral stakes, or rebar provides support for vining plants season after season. Wrap the tepee with twine to give the plants horizontal supports on which to climb.

Sugar snap peas (1): Substitute green peas or snow peas.

Collard greens (2): Substitute cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale, or mustard greens.

Lettuce (3): Substitute carrots, radishes, dill, parsley, or cilantro.

This bed shows a variety of plants, but if your family doesn’t care for one of the vegetables or herbs shown, feel free to make substitutions.

Cherry tomatoes (1): The plant has rambling vines that bear fruit all summer. Training the vines around the tepee and not just up the legs of the support will help handle the plant’s vigorous growth. You can also tame unruly vines by pruning them midsummer.

Peppers: Plant any variety you like, including serrano, cayenne (2), bell (3), habanero, jalapeño, and Thai chile. If your plants grow large, add a tomato cage for additional support.

Lemon thyme (4) and chives (5): These are perennial herbs that, once planted, will carry through from season to season unless they’re transplanted to another location.

Eggplant (6) and basil (7): Plant any varieties you like.

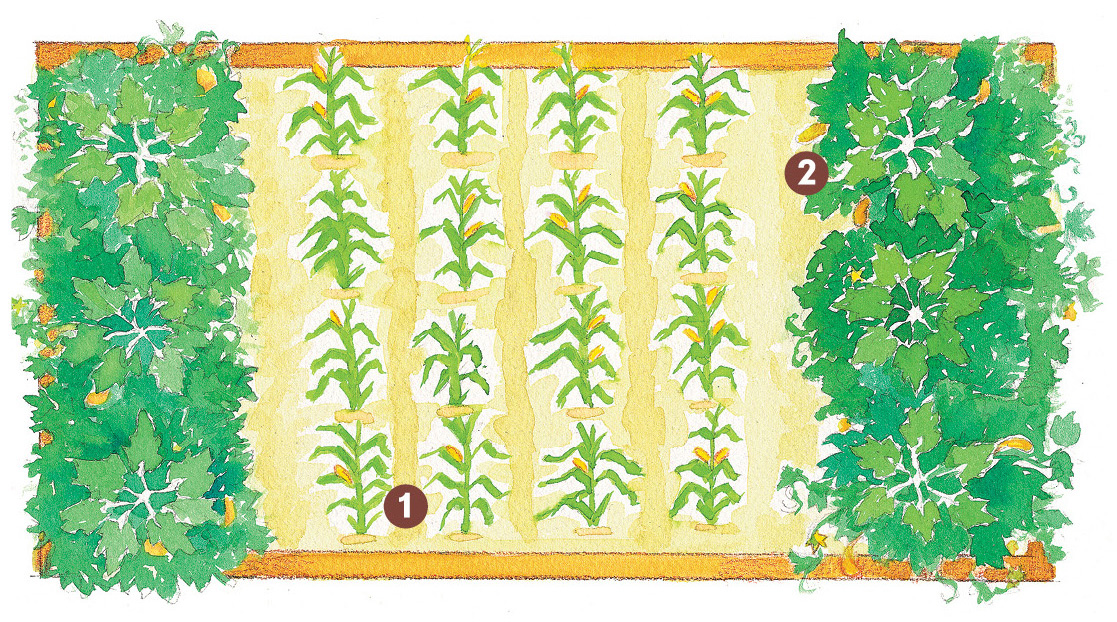

Corn (1): Plant in a block of four rows by four rows for the best pollination.

Squash (2): Substitute crookneck, straightneck, zucchini, or pattypan squash.

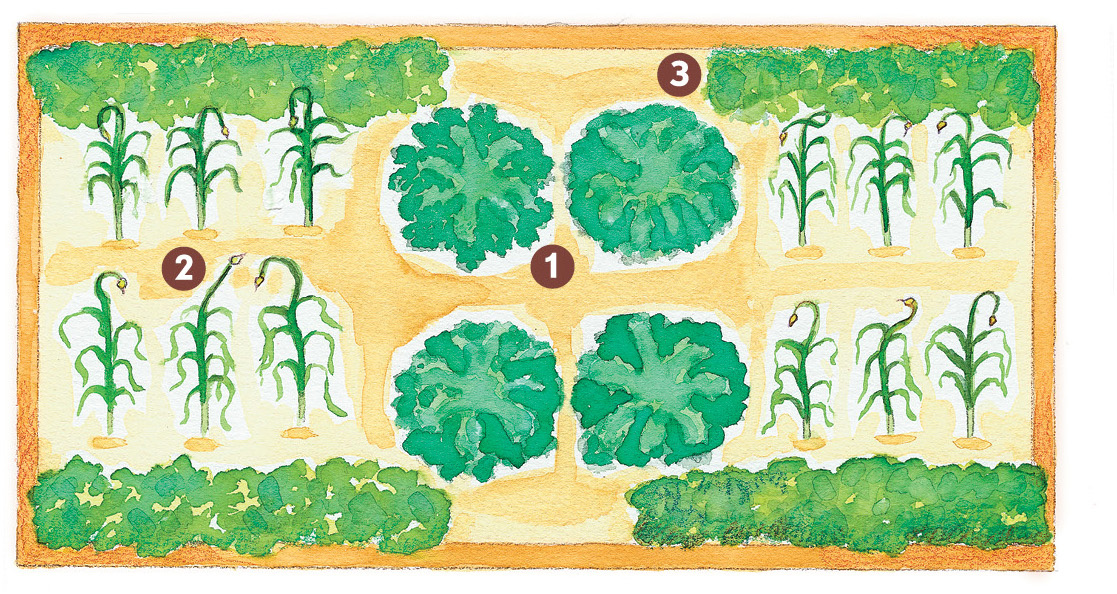

Kale (1): Substitute collards, broccoli, cauliflower, or Brussels sprouts.

Garlic (2): Substitute onions.

Arugula (3): Substitute lettuce or other salad greens. Stagger planting one corner every few weeks for a continuous harvest.

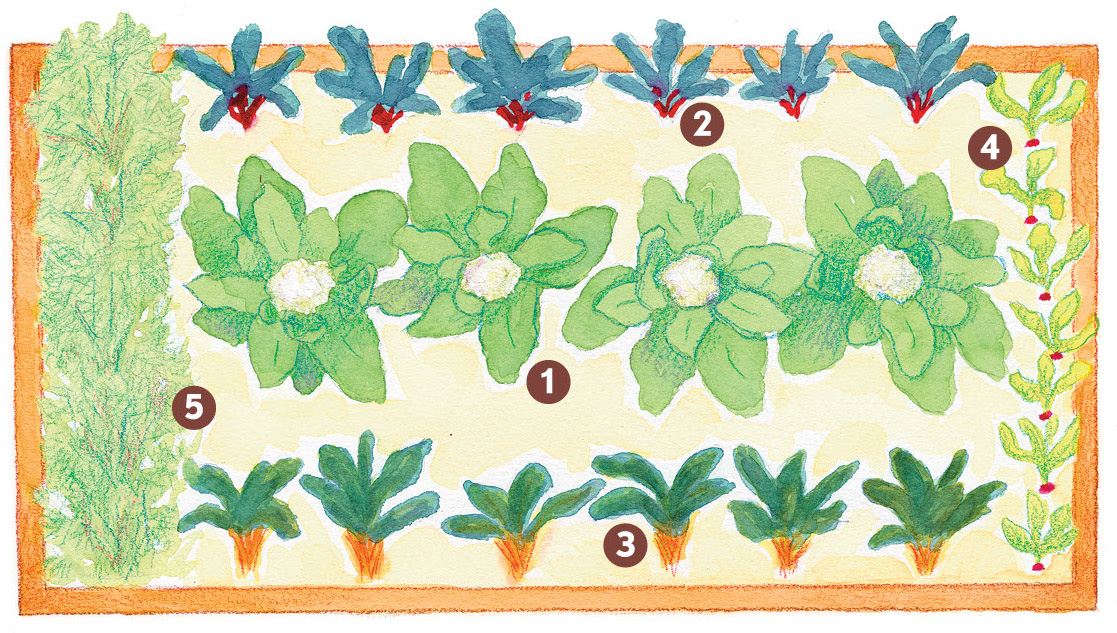

This bed features a raised diamond-shaped bed in the center, which is intended to be elevated with additional timbers to create deeper soil.

Broccoli (1): Substitute cauliflower, cabbage, kale, or collards.

Carrots (2): Substitute radishes, parsley, or arugula.

Green (3) and red (4) lettuces: Substitute leaf lettuce, romaine, or a mix of different types.

Sunflowers and pole beans (1) : In the summer, plant the center section with sunflowers. After they reach 3 to 4 feet tall, sow pole bean seeds at the base of the stalks, using the sunflowers as a homegrown trellis.

Bush cucumbers (2): Substitute summer squash or bush-type watermelons.

This traditional row-type layout lends itself to a variety of options.

Cauliflower (1): Substitute cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale, or mustard greens.

Swiss chard: The red (2) and yellow (3) varieties shown in this design make a pretty contrast to the blue-green of the cauliflower in the center of the bed. Substitute Asian greens, such as pak choi or bok choy.

Radishes (4) and dill (5): Radishes grow quickly, which means you can replant as soon as they’re harvested and get in a few plantings each season. Substitute cilantro or parsley for both the dill and the radishes, if you like.

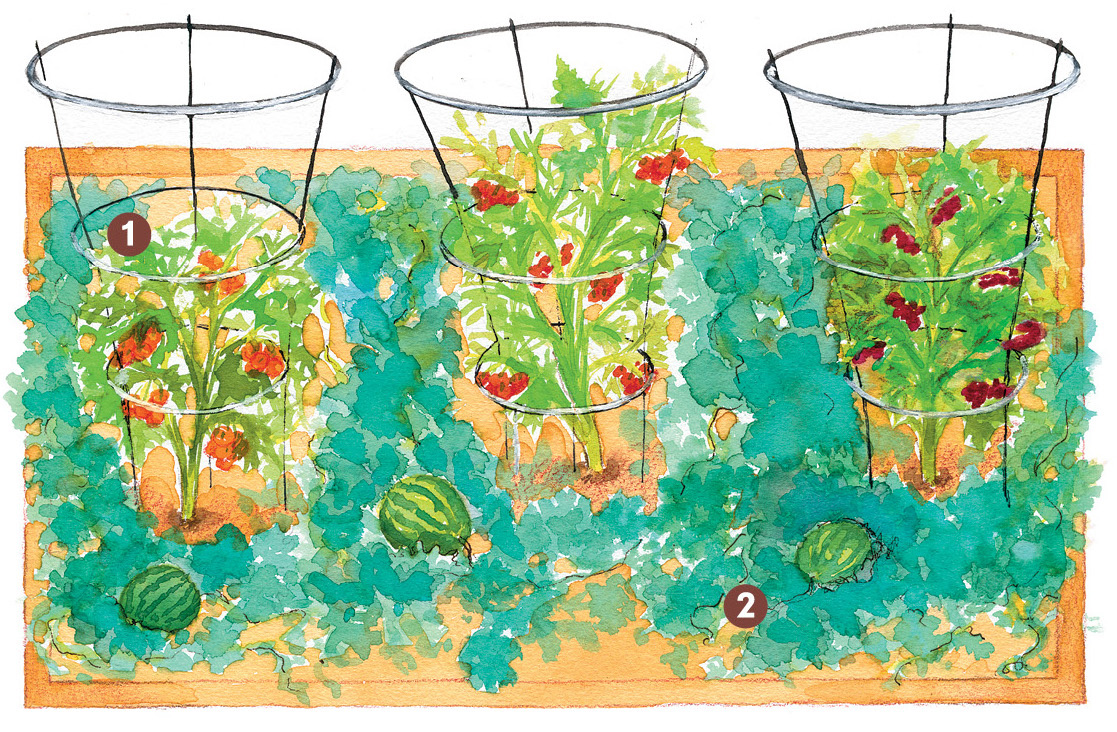

Tomatoes (1): Three tomatoes grown in cages give you an opportunity to try a few different varieties. Choose three options for variety in color and timing so you’ll have tomato-y goodness all season long. Determinate varieties are recommended for these smaller tomato cages, but if you prefer indeterminate tomatoes, use two large cages that are 3 feet in diameter and 6 feet tall. They’ll need to be made of sturdy wire fencing with openings large enough for you to reach through. Be sure to anchor these larger cages by tying them to rebar hammered into the soil.

Watermelon (2): Unlike the bush type, vine watermelon needs room to ramble. Plant just one, and train the vines to cover the bed rather than the path around the bed. Substitute pumpkins, winter squash, or melons.

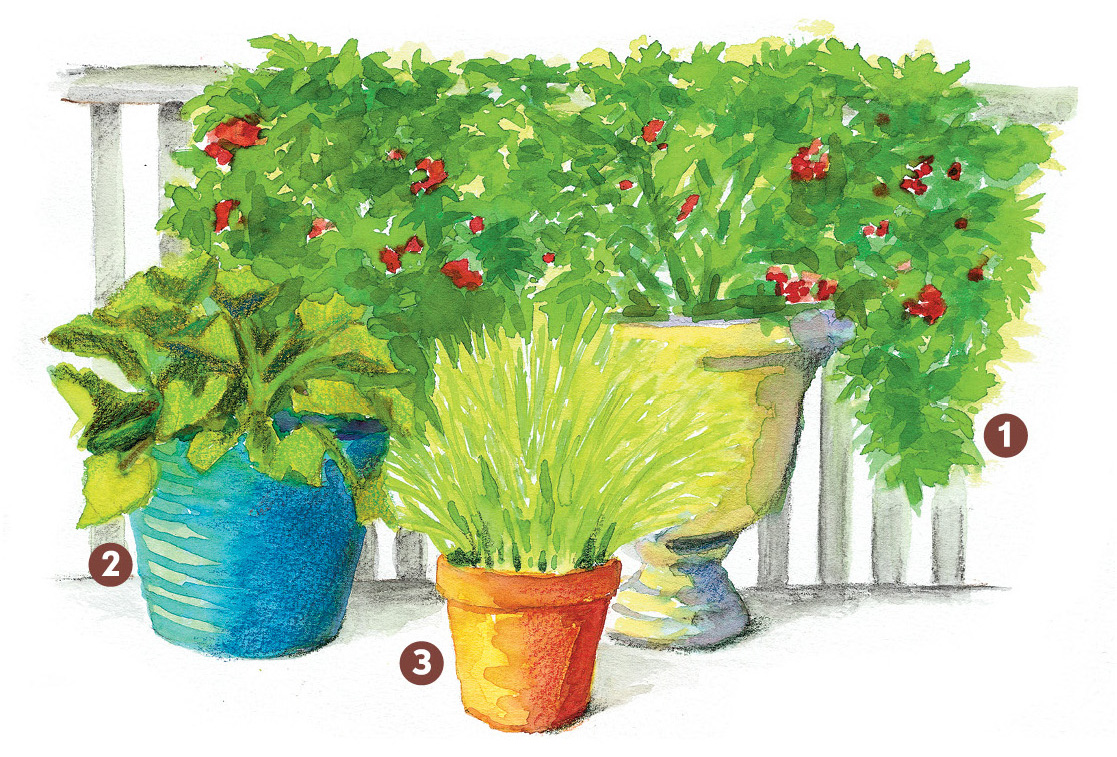

Containers For containers, a grouping of three or more pots of differing sizes is a great way to get a variety of produce from a limited amount of space. A good base will include a large urn with lots of room for roots, accompanied by an 18- to 24-inch pot and a smaller 12- to 14-inch pot. Choose lighter-weight material for those placed on a patio or balcony, which may not be able to handle the weight of heavier containers.

Tomatoes (1): Plant tomatoes in a larger urn, and choose varieties bred for containers, such as Patio or Sweet ‘N’ Neat, which can be grown without support. You can also plant a determinate (Better Bush, Bush Early Girl, Bush Goliath) or dwarf indeterminate (Husky Cherry Red) that can be supported using a tomato cage or homemade tepee. If you have an area next to a railing or fence that gets adequate sunlight, you’ll have more options because the vines can use it for support.

Zucchini (2): One plant can be quite prolific in an 18- to 24-inch pot. Substitute crookneck, straightneck, or pattypan squash.

Chives (3): Perennial herbs such as chives or thyme can remain in a small pot year-round. Substitute creeping thyme or Spicy Globe basil.

If the plants don’t live through the winter, replant them again in early spring before the last frost.

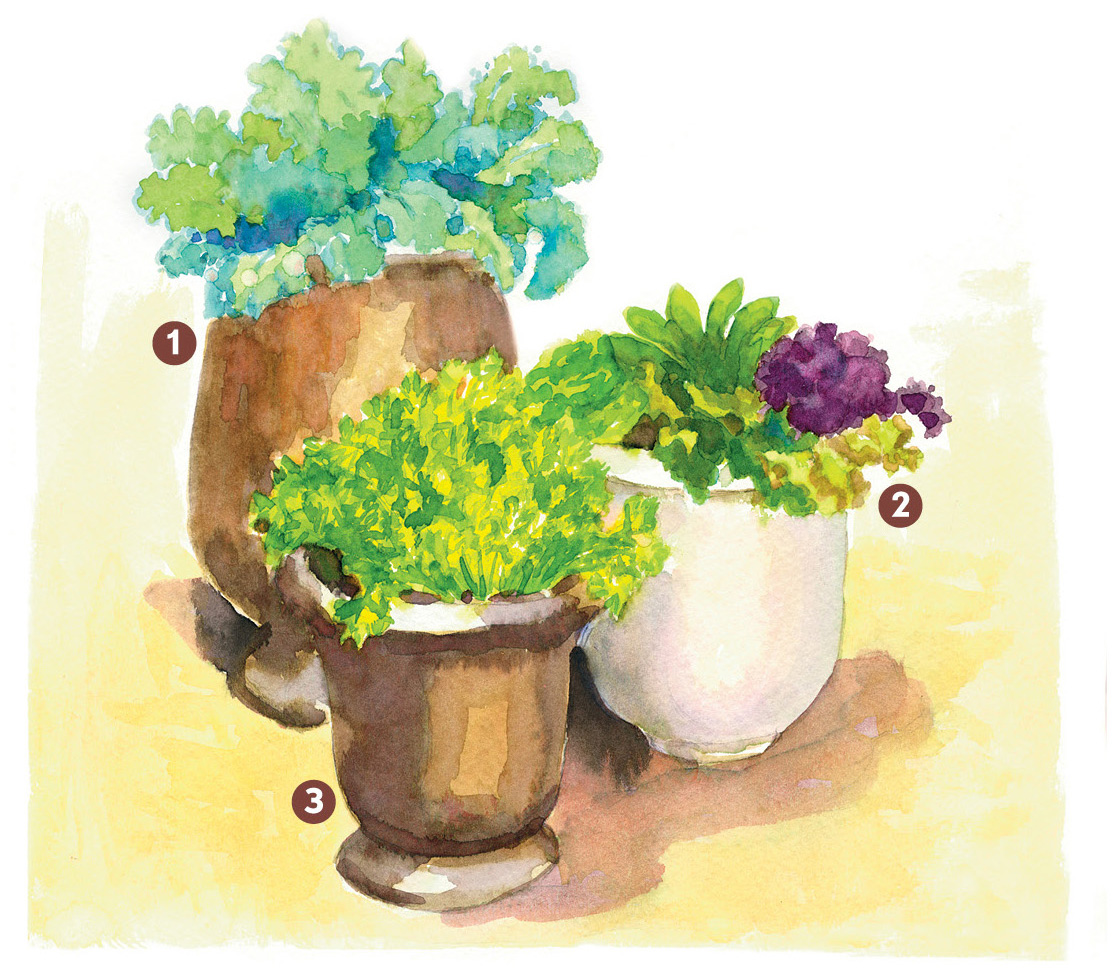

Kale (1): Substitute cabbage, broccoli, mustard greens, cauliflower, or Brussels sprouts.

Lettuce (2): Potted lettuce won’t provide endless salads, but it’s ideal to supplement store-bought greens and provide enough for sandwiches.

Cilantro (3): Substitute parsley, chives, or dill.

Potted herbs are ideal for those who’d like year-round seasoning at their door.

Rosemary (1): A large urn is perfect for a large plant like rosemary. This woody shrub is cold-tender and better suited for gardeners in warmer states, although it will tolerate temperatures in the 20s without a problem. Choose a cold-hardy variety, such as Hill Hardy and Arp, for those areas where temperatures dip into the teens. Until the rosemary grows large, creeping thyme (2) can be planted on the sunny side (south or west) of the pot to trail over the edge.

Basil (3): Plant basil in an 18- to 24-inch pot. This annual is only perennial in gardens that are frost-free. Plant any variety you’d like.

Parsley (4): Plant parsley in a small pot. Substitute chives, creeping thyme, or mint.

Water is essential and is at times in short supply. To make it through the good times and bad, encourage deep rooting by having loose, porous soil and keeping your garden covered with mulch to minimize water loss through evaporation. Drip irrigation, a method of trickling water from tubes slowly and directly onto the surface of the soil, is recommended for gardeners in drought-prone areas. It’s beneficial because no water is lost to evaporation or runoff.

A good rule of thumb is that gardens need about an inch of water each week. However, this measurement doesn’t take into account variations in water use due to temperature, humidity, and how close plants are spaced from each other, so you may need to tweak this to fit the needs of your garden. By regular observation, most gardeners quickly figure out which plants wilt first, which is a useful indicator when you are first learning watering cycles. Ideally, you should avoid stressing the plants: Apply water before the soil dries out. Wet the soil thoroughly to encourage deep rooting, and then avoid watering again until it’s needed. Overwatering can be just as detrimental as underwatering.

The same principle applies when watering containers, although container-grown plants will need water more often than in-ground plants. Be sure to water containers until you see water spill from the bottom of the pot to ensure the soil is thoroughly moist. When the weather is hot, they may need water daily. Mulch will also help conserve moisture in containers: Use small bark nuggets; they’re easy to turn into the soil at season’s end to enrich it further. Also, mulch herbs with small pea gravel; it protects foliage from soil splatter and is helpful in humid climates.

Fertilizer is one way to supply the nutrients essential for a productive garden. The key is to use the right kind and apply it in moderation.

The most common fertilizers are made from salts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, nutrients used by plants in the largest quantity. You’ll see them labeled as N-P-K: 5-10-10, 20-20-20, or similar. The three numbers are the percentages of those three nutrients in the product. Because they are salts, too much can kill your plants. Use the product in the amount recommended on the label to help your plants flourish.

Overfertilizing can also delay harvest. Plants that must bloom in order to produce their fruit (tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, squash, cucumbers, melons, beans, peas, and okra) need a balanced approach to nutrition. If they get too much nitrogen, they’ll grow a lot of foliage and flowering will be delayed.

Usually a dilute liquid fertilizer is used when transplants are set in the soil, followed in a week or two by granular fertilizer or timed-release granules applied at the rate recommended on the product label. Reapply as recommended, as different products remain active in the garden for varying lengths of time.

Organic gardeners use compost and other amendments, such as kelp, fish emulsion, cottonseed, and soybean meal to enrich the soil and feed the worms and soil microbes. This plant-feeding system works quite well, and it has long-term benefits.

Mulch is organic material that hasn’t yet decomposed. It reduces evaporation, which keeps soil moist and cool. It also prevents weeds. Common choices include pine needles, tree bark from various species, wheat straw, and even newspaper and pasteboard boxes. If papers are used, be sure to cover them with another mulch or they’ll blow about on windy days. Areas covered with four to five sheets of newsprint or flattened boxes are certain to be weed-free. Avoid rubber mulches that don’t break down; you want mulch to decay and enrich the soil.

Pests are part of gardening and take many forms: mildew that disfigures your cucumber foliage, tomato hornworms eating every leaf from your plant, or deer feasting on blueberries. Solutions vary, too, from chemicals that require careful and knowledgeable application to traps that simply capture the problem.

One of the most common problems is the havoc hungry wildlife can wreak on your garden. Birds peck ripening fruit, opening them to invasion by bacteria and ants. To keep them at bay, drape small and medium-sized fruiting plants with bird netting, use fake snakes and owls to scare them away, hang reflective tape on the plant, or simply plant enough to share with them. Remember, some birds damage fruit, while others eat the caterpillars that are eating your plants.

Deer can also be troublesome, eating fruit and foliage and trampling your hard work. Where there is consistent damage, try repellents or use motion-activated sprinklers and lights to keep them away. If those fail, consider installing a deer fence to protect your produce.

Keep in mind that any chemical used in the garden should be considered carefully before applying since it will also affect the fruit, vegetables, and herbs you’re growing and could harm the bees that pollinate the flowers. General insecticides also harm beneficial insects that deter or rid your garden of troublesome ones. There are many solutions, from organic to homemade to commercial tried-and-true. Please consult your garden center or Cooperative Extension office for guidance.

Compost is a simple way to add nutrient-rich organic matter to your soil. Whereas fertilizer feeds the plants, compost feeds the soil, promoting the health of microbes that aid in plant growth. In addition, the organic matter in compost helps clay soils become lighter and more porous, and it helps sandy soil hold more moisture. No matter what kind of soil you have, compost makes it better. You can buy compost, but homemade is best.

Composting may sound intimidating, but it’s easy. A mounded pile of leaves, branches, and other trimmings in a corner of your yard will eventually decompose without any work required, yielding a rich soil amendment. This process can take up to a year to produce results, but can be sped up by creating optimum conditions for the helpful organisms responsible for decay. You’ll need the right mix of air, water, and materials rich in nitrogen and carbon. Sound complicated? It’s not.

Anything that was once a plant can be composted. Your kitchen and yard will provide plenty of material. You’ll need about twice as much by volume of brown matter as green matter. Brown matter comes from trees and is high in carbon. It includes dry leaves, hay, sawdust, wood chips, and woody trimmings. Green matter is fresher, wetter, and high in nitrogen. Generally, it comes from garden and kitchen waste, such as grass, food scraps, and animal manure (but not dog or cat droppings). Avoid plants that are diseased or infested with insects, weeds with seeds, or hardy weeds that could survive composting. To speed the process, shred or chop large materials. The summer season is rife with green matter, so be sure to layer in plenty of browns to keep the compost from getting soggy. If you lack brown matter, use shredded newspaper.

Include:

Browns

• Leaves

• Twigs

• Pine needles

• Shredded newspaper or cardboard

• Straw

• Sawdust

• Cornstalks

Greens

• Fresh grass clippings and weeds

• Eggshells

• Coffee grounds

• Tea

• Fruit peels and trimmings

• Vegetable trimmings

Avoid:

• Meats

• Bones

• Dairy products

• Oils and greasy waste

• Pet droppings

There are a number of composting options to suit your space and needs: freestanding piles; homemade structures; or plastic compost bins, tumblers, or barrels sold at garden centers.

To create an open-air pile, begin by layering materials until the pile is 3 to 5 feet tall and wide—anything larger may not allow enough air to penetrate to the center. Apply water between each layer, but don’t add so much that the pile becomes soggy or saturated. Once you’ve finished layering, sprinkle the pile with topsoil or previously composted material, which will infuse it with the microorganisms needed to start the decomposition process. The pile will heat up in just a few days. If left unattended, the pile will decompose slowly on its own. Turning it regularly introduces oxygen to the interior, which will speed the process. As you add new scraps, completely cover them within the pile.

If you don’t have room for a compost pile, you can leave one garden bed unplanted each season and bury buckets of scraps from the kitchen every day or two. The earthworms will have a feast. After two weeks you’ll find little left but the eggshells, which take a bit longer to break down. Just keep it covered in mulch to keep weeds down.

If most of your compost materials come from your kitchen or if you don’t have the yard space, an enclosed container is a good option and will keep animals at bay. Layer as you would in an open-air pile, and turn it regularly.

Good compost has an earthy smell. If your compost smells rotten, it’s a sign there’s too much water or too many greens. Turn it more often, reduce the amount of greens you add, or apply more brown ingredients to balance the pile.

If you opt to go organic in your garden, these are the common practices. Always read labels carefully. Just because they’re safe for food does not mean that they won’t irritate or harm you if used improperly.

• Bt, or Bacillus thuringiensis, is a bacterial parasite of the larvae of butterflies and moths that can be sprayed or dusted. It combats troublesome larvae, including cabbage worms, cabbage loopers, tomato hornworms, and corn earworms.

• Copper fungicide is used to prevent fungal diseases of fruit. It can also be mixed with a dormant-oil spray in winter.

• Horticultural oils include dormant-oil sprays applied to fruit trees to smother overwintering insects. Use growing-season sprays carefully, as sun can be damaging after spraying.

• Insecticidal soap kills mealybugs, aphids, spider mites, and more with no residual effects.

• Kaolin spray is used as a protective coating on fruit trees for a variety of insect pests, as well as on some garden plants, such as squash, that are vulnerable to borers. Spray before the problems arise.

• Lime sulfur spray has long been considered the least toxic treatment for fungal problems, such as brown rot on peaches and cherries.

• Neem oil comes from the seed of a tropical tree and is effective against certain insects, mites, and fungi, but it should be used with caution. Apply when bees are not working.

• Spinosad is a biological insecticide used to control pests in organic gardens. Use against fire ants in the food garden, as well as against roly-polies (pill bugs). Use sparingly in consideration of beneficial insects.

• Sulfur spray can be used as a fungicide, insecticide, and miticide. It is commonly used for powdery mildew on grapevines. It can be irritating, so wear protective clothing as recommended on the label.

Gardening is a simple yet rewarding way to spend time outdoors, reconnect with nature just outside your door, and have something delicious to eat. Not everything will work out like you plan, but some of it will—in fact, most of it will. If you have fun growing the greens for your salads or pears for preserves, then your hard work has been rewarded.