One of the hot curl boards I built. Mickey Muñoz

The Evolution of Speed

One of the hot curl boards I built. Mickey Muñoz

The paipo boards from Hawai‘i influenced me the most as I started to understand, through repetition and observation, more about surfboard design and what really works in the water.

Paipos, made from plywood veneers, were almost triangular in shape with the front point of the triangle tipped up and the two opposing corners tipped down like fins. They had pretty flat bottoms and were planing vehicles. They were very radical and very efficient. You had to take off really late because you were swimming into the wave, but once they got up and planing, they were fast.

Proof of that speed could be seen at Waimea Bay on big days when Buzzy Trent was riding one of his 11-foot, radical, pintailed guns. He would drop into these horrible maws and aim for the bottom; if he could make it to the bottom, he could make the wave. Nobody on a surfboard was going faster, deeper, or bigger than he was at the time. Those paipo guys would drop in after Buzzy would be a third of the way down the face of the wave; once they got up to speed, they would rocket by him like he was standing still.

The problem with standing on something like that, though, was that the board was going airborne. At that time, to go airborne on a board and still maintain your balance was not easy. The boards were bigger and heavier and not as maneuverable; if you did go airborne and you didn’t land perfectly, you went down. On paipo boards, the rider was prone, hanging onto the board, and just rocketing.

The next influence, George Greenough, came a little later. I was at Rincon on a really good day, and it was the first time I saw somebody make a full carving S-turn without breaking the plane. Again, he was on his knees holding onto the board, still able to go airborne and maintain, but he could carve that board while he was going really fast.

Simmons had the same vision with his boards – concave bottoms, turned down rails in back, and twin fins – they were ahead of their time. The paipo board and the Greenough spoon were both basically the nose and tail of a Simmons board stuck together. Shorten the Simmons board from 10 feet to 4 or 5 feet, and you’ve got what Greenough and the paipo guys were riding.

Long and narrow was not necessarily better than short and wide. Shaping is all about balancing control and speed. We love to go fast; speed is your friend but only if you can control it. So you juggle and balance those two factors when you are shaping. I found it fascinating then, and I still do.

Waves in Hawai‘i have plenty of speed. The wave train is moving faster than the coast here, because Hawai‘i doesn’t have a continental shelf. Our bottom gradually gets shallower and shallower, and the wave train slows down earlier. By the time it gets to the point where it can trip and break, it’s slowed down considerably compared to Hawai‘i, where waves come in from very deep water. There are places in California like Black’s Beach or Hollywood by the Sea that have a trench or underwater canyon. The wave trains getting into those spots don’t slow down as much; it breaks substantially harder and quicker at Hollywood than it does at C Street just up the coast.

Building speed into your boards is no good unless you can control it. You are trying to make the boards fast but controllable. It’s a balance that depends on where you are surfing, the type of wave, and how big it is. Up in Ventura, you’ve got two radically different waves within 10 miles of each other. You would design a different board for Hollywood by the Sea than for C Street.

The next influence came from a trip to Australia in the early ‘60s when the shortboard thing was just starting. As soon as we landed in Sydney and I met Bob McTavish, we were like long-lost brothers; he really influenced me. McTavish showed me one of his radical concave, vee-bottom boards, and after I came back, I made a bunch of very short boards with wide tails and deep-vee bottoms. Those boards were both faster and more maneuverable than the standard boards of the day.

Phil Edwards working on El Gato, the catamaran he designed and built. Poche. Mickey Muñoz

One of my experiments; I think it ended up as a twin fin. Mickey Muñoz

A couple of replica boards I made for Pete Siracusa to hang in his restaurants. San Onofre. Mickey Muñoz

A nicely foiled fin. Mickey Muñoz

I helped build this composite motorcycle fuselage for a guy that was trying to break the world speed record. He went 120 mph without even getting out of second and was well over 300 by the time he got through the rest of the gears. Bonneville Salt Flats. Mickey Muñoz

For every board you shape, your point of view is from the past; it’s based on what you’ve learned in the past. You carry all this stuff in your head – you may not overtly think about it, but it’s there – and it’s expressed every time you shape a board. My boards are shaped by those encounters with paipos and Greenough and McTavish and countless other experiences.

My friend Richard Tracy, an aeronautical engineer who got a PhD in hypersonic aerodynamics at Cal Tech, has been mucking around with foils most of his life. He’s pushing 80 now and that’s all he’s done. A few years back, he made an incredible breakthrough on a foil that he had been working on for 20 plus years. He made a subtle change from the shape he had been doing. That subtle change made a huge difference in the overall design and performance of the plane he is designing and building. That plane can fly supersonically, and also subsonically, with much greater efficiency. It was just a subtle tweak in the shape of the foil. That’s why surfboard design and surfing is such a hook for me: If the last wave or the last board shaped was good, the next one is going to be better.

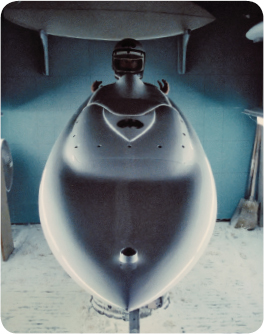

Bob Montgomery came to me for help building his concept of a jet board. This is what we came up with after a year or so of hard work. With a 40-horse engine and 120 pounds, he got it up to 50 mph and could surf waves with it. He’ll get them into production one day. Mickey Muñoz Collection