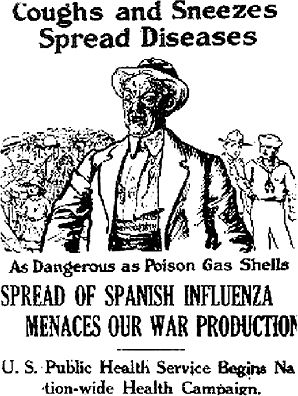

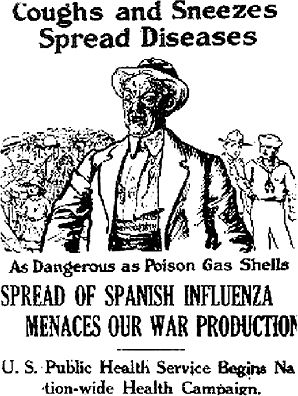

The year from spring 1918 to spring 1919 saw one of the worst epidemics — perhaps even the worst — in human history. The Spanish flu raced around the globe, killing 20 to 50 million people. That's a higher body count than World War I. More than the “Black Death” in medieval Europe. The Human Virology website at Stanford University explains:

An estimated 675,000 Americans died of influenza during the pandemic, ten times as many as in the world war. Of the US soldiers who died in Europe, half of them fell to the influenza virus and not to the enemy. ...

The effect of the influenza epidemic was so severe that the average life span in the US was depressed by 10 years. The influenza virus had a profound virulence, with a mortality rate at 2.5% compared to the previous influenza epidemics, which were less than 0.1%.

The Encyclopedia Britannica avers: “Outbreaks of the flu occurred in nearly every inhabited part of the world...” Some people died less than 24 hours after catching the bug. Oddly, it was most likely to cut down young adults, rather than the usual targets of influenza — children and the elderly.

You get the idea — it was a worldwide catastrophe that could've easily caused societies to crumble. Thank goodness it could never happen again. Well, that's actually not a sure thing. Not content to leave well enough alone, scientists are in the process of recreating the Spanish flu virus.

Dr. Jeffrey Taubenberger from the US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology found portions of the killer in tissue samples from the time period. He and his colleagues were able to decode several genetic sequences, which they published.

Taking it to the next level, they teamed up with other scientists to partially resurrect the virus. In 2001, they spliced a gene from the 1918 flu into a run-of-the-mill flu virus. The next year, they did the same trick, only this time they added two 1918 genes into the mix. The resulting patchwork virus killed mice at a much higher level than current strains. The Sunshine Project, a watchdog organization fighting the development of biological weapons, warns: “This experiment is only one step away from taking the 1918 demon entirely out of the bottle and bringing the Spanish flu back to life.”

Why take such a huge risk by reanimating a defunct killer of millions of people? The scientists have varying explanations. To study influenza in general. To figure out what made this virus so deadly and if it could happen again. To develop a vaccine against the 1918 virus (which no one would need if the virus weren't brought back in the first place). Simply because the scientists wanted to test out some new techniques, and, as Taubenberger told the American Society for Microbiology: “The 1918 flu was by far and away the most interesting thing we could think of...” Yet another reason was to keep the Institute's massive collection of 60 million tissue samples from being tossed out as a cost-cutting measure. Taubenberger: “Everyone was bending over backwards to see what part of the government they could cut away next, so I want to make my own little contribution and point out why it would be prudent to keep this place in business.”

While those first two goals are worthwhile in theory, we might sleep more soundly if they were approached in different ways. Couldn't scientists just examine the genetic code without actually cooking up the virus? Won't computer simulations work? If you trust that harmful viruses don't escape from labs, you haven't read the Department of Agriculture Inspector General's report on lax conditions at facilities housing these nasty beasts. This 2003 tongue-lashing said:

Security measures at 20 of the 104 laboratories were not commensurate with the risk associated with the pathogens they housed. These 20 laboratories represented over half of the laboratories in our sample that stored high consequence pathogens. Alarm systems, surveillance cameras, and identification badges were commonly lacking in buildings housing the laboratories, and key-card devices or sign-in sheets were not generally used to record entries to the laboratories.

It gave this reassuring example:

We discovered a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) select agent at one institution that was kept in an unsecured freezer and for which no risk assessment had been made. The agent, Yersinia pestis, causes bubonic and pneumonic plague and requires strict containment. The freezer that stored this agent had not been inventoried since 1994, when a box of unidentified pathogens was already noted as missing.

Hmm, I'm feeling a little feverish....