CHAPTER THREE

MY EARLY YEARS

The human memory is a wonderful thing. After spending seventy years on this earth, I can still remember snatches from the time I lived with my family on St. Jarlath Road in what is still called “Old Cabra” on the north side of Dublin. I was born on the twelfth of October 1938 in the Rotunda Hospital, Parnell Street, just off the top of O’Connell Street. My mother told me much of what I know now about those years, as I got older. She told me for example, that Éamon De Valera’s son was the consultant obstetrician, and he asked her what name she had chosen for me. She replied that she hadn’t yet decided, whereupon he suggested that she call me after his father. Being a Republican and an ardent admirer of “Dev,” she decided to do just that.

I can recall sitting on the curb-side near the number twelve bus stop, which was close to the traffic island that is there now with the shrine to “Our Lady” on it. My father was late and had missed the bus. One of our neighbours, who normally sat beside him on their way home from work, told me this and offered to bring me home. I wasn’t having any of his stories and refused to budge.

He called in to my mother on his way home to tell her about my father, and where she could find me. She almost had a heart attack. There were so many children in the house; she hadn’t noticed that I was missing, especially as she had a new baby to care for. She quickly despatched one of my sisters to get me. A short time later, she arrived at the bus stop and dragged me kicking and screaming all the way home. There was no consoling me by all accounts, as my mother tried to explain why my father was late and that he’d be home soon. One might be forgiven for thinking that my behaviour was that of an only child. But, I had been born into a large working class family of twelve children and I was ninth in line. That’s not quite accurate actually. While there were twelve of us in the family, the eldest was a half brother. My father had a relationship with another woman. He fathered a child who was three months older than my eldest sister. Why my mother didn’t throw him out, I’ll never know. Far from doing that… she took the child in when he was six years of age after his mother abandoned him. He was treated as a brother by all of us; this, despite our knowing that something wasn’t quite right when it came to birthday time for him and my sister Alice. He told me the whole story just before he died at eighty-three years of age.

My mother, like many women of her day, actually had twenty-three pregnancies. She lost at least two children in the four years that separated my older brother and myself. She certainly earned her sainthood. My sister Olive was born eleven months after me, and she was now the baby of the family. We were what became known as “Irish twins.” So there’s no explaining why my father took to me in the way that he did. We were great friends all through my life. He spent more time talking to me about things in general and his army service in particular, than any of my brothers and sisters. I hero-worshipped him anyway, and he obviously appreciated that. I think that the gap in years between my brother Jim and myself allowed my father to spend more time with me as a baby than he did with any of the rest of my brothers. Because of this, I became so attached to him that he couldn’t go anywhere without me following him. If he wanted to slip out for a pint or just leave the house on his own for any reason, he would leave his coat upstairs and tell me he was just going up to get something from the bedroom. He would then throw his jacket out of the bedroom window, come down again and tell me he had to get some coal for the fire from the outside coal-shed. He would then collect his coat from the garden and run down the road. I got wise to his tactics after a short while and I would insist on going outside with him.

So, he then took to bringing me up to bed, he would lie down beside me and twirl my hair, which I loved, and it would put me to sleep. I got used to that also and more times than not, my father would fall asleep instead. I got a terrible time from my siblings over this when my mother and father would reminisce about it, among other things as we sat ‘round the fire, years later.

I became known as “Daddy’s Blue-eyed Boy,” and I was subjected to some terrible verbal abuse. There was worse to follow at school. I became introverted and shy as a result, and I would blush terribly in the company of strangers, particularly women.

As I stated earlier, my father had been a member of “E” company 1st Battalion Old IRA, during the War of Independence. He stayed with the Republicans during the Civil War and kept his handgun fully loaded in an air-vent in his bedroom. As the family numbers increased, he and my mother moved into a smaller room (forgetting the gun) and gave up the larger one to my sisters. Alice, the eldest was searching around one morning and found the gun. She pointed it at May, another sister and said, “Stick em up,” she pulled the trigger and the gun went off with a tremendous roar. When the screaming stopped, it was found that the bullet had penetrated the bedpost just inches from my other sister’s head. My mother went ballistic and insisted that my father get rid of the gun. He took it with him next morning and threw it into the river Liffey.

My godmother, Mrs. Alice Swords, lived across the road from our house. She looked after me most of the time, so my mother said. It always amused her that my godmother used me like the Artful Dodger in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist to steal vegetables from Reid’s shop on the Cabra Road. The footpath outside of the shop was very wide indeed (it now has a Service Road cut out of it) and Mr. Reid used to get his staff to display the fruit and vegetables on raised boxes on the footpath. It looked like a carpet to all intents and purposes. Mrs. Swords would park my pram right up against the side of the display. It was just the right height for me to reach out my hand and lift whatever goods were nearest. She would then come out of the shop with her bag of messages in hand and put it into the pram covering whatever I had taken. Whatever it was, my mother told me later that I was the best-fed kid for miles around. I wonder if that’s why I still love vegetables today, and have most of my own teeth and hair. The earliest photo of me certainly bears out what my mother said. I have a belly on me like an old beer drinker.

I don’t have any memory of leaving Cabra. But I do remember that the next place we lived in was not nearly as nice. It seems that my father was out of work, perhaps due to a strike, and as there was no dole in those days, he had to find some way of earning money to keep the wolf from the door. These were desperate times and service to the nation counted for nothing when it came to men of his ilk looking for a job. Many of the employers were British or Protestant anyway, so there was no hope of them employing an ex-IRA man. This included his ex-employer in the Marble Trade. The newspapers at the time carried job advertisements that stated, “No Catholics need apply.” He was prepared to do anything and spent many long hours seeking some sort of employment.

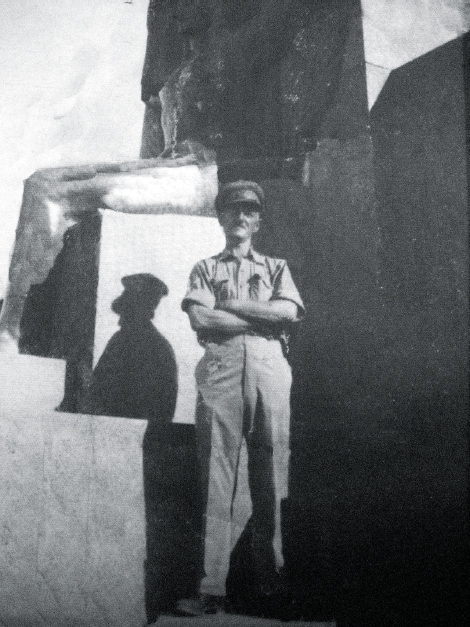

The Second World War had broken out and like many Irish men before him, he joined the British Army. This didn’t sit well with his old comrades, who were of the group of die-hards that had not accepted the Treaty with Britain. His only interest was feeding his family and paying the household bills, and since they weren’t offering financial help or employment, he felt he had no choice but to do what he was doing. After his basic training, he was posted to North Africa and was involved in the Desert Campaign with the 8th Army. He went on to Sicily and Italy after that. My eldest brother Paddy and my sister May left around this time to work in England. Paddy went to London and May worked in a cotton mill in Oldham, Lancashire.

During his time in North Africa, my mother received a telegram from the British War Office stating that he was missing in action, presumed killed. She, naturally, was in a hell of a state; she could not see how she could keep up with the rent on the house and feed a large brood. So she handed back the keys and moved into rooms in a tenement house in Bolton Street. The house stood on the site where the extension to Bolton Street College of Technology now stands. I’m not sure if the rent was in arrears anyway, but I do know that my father had been on strike for thirteen weeks at one stage without any strike pay, and this would certainly account for the dilemma my mother found herself in. No one has ever said this, though it seems logical to me. Dublin Corporation had a reputation as one of the most egregious landlords in the city. They didn’t hesitate to evict defaulting tenants even from the filthy tenements that they owned, and she wouldn’t have wanted the embarrassment of being evicted. People of that era were so private about things like that. They would’ve been ashamed to admit to anyone that they were in financial trouble.

That strike was a blessing in disguise for me, though. My father got some odd jobs to do for a doctor who lived in Ballsbridge, before he joined the British Army. He had a son who was about my age and the doctor gave my father some of his son’s cast-off clothing. At one stage, I went around dressed in a full naval captain’s uniform, complete with cap. My brother Jim used to go nuts when my sister Rosaleen would tell him that he went to school dressed as a Japanese General.

Six weeks after we moved, another telegram arrived announcing that they found him and he was on a hospital ship heading for Tripoli. I learned much later in life that he went to help a pal who had been hit and as he bent down to pick him up, a shell landed beside them, blowing him and his pal quite a distance into the desert. His unit moved on and a following unit found him. His pal had been blown to smithereens. When they found my father, he was bleeding from every orifice and it was touch and go as to whether he would survive. My mother was, needless to remark, overjoyed. I was too young at that time to appreciate the significance of it all.

However, I wasn’t too young to remember being called by my brother Jim one day and him saying, “Look… look,” as he pointed to the sky. What I witnessed is still as clear in my mind today as if it had just happened. There were two planes, one chasing the other, with its guns blazing away. I later learned that it was a Spitfire chasing a German bomber. I believe that the bomber crashed into the sea near Howth.

My mother told me that I accused my uncle, James Byrne of being responsible for my father going away in the first place. All the family called him Jamesie. He had lost a leg in the First World War, while serving in France with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. He was wounded on the Somme in July 1916. He had helped my father with filling in the forms for joining up. My father had brought me along to 61 Upper Dominic Street where the Byrnes, among others of our family lived, including my Grandparents and I witnessed what went on between them. It was an old tenement, and various relations completely occupied it.

The Campbell’s lived on the ground floor, the Byrnes on the first floor, then the Ryan’s on the second floor and finally my father’s parents on the top floor front. All of these were closely related, i.e., brothers and sisters, cousins and aunts, with their respective wives, husbands and children. It still puzzles me even today as to why my grandfather, who had a good job as a coachbuilder with the Great Southern Railways, lived in a tenement.

Jamesie was quite a character and liked his pint of stout. The British Medical people had issued him with two wooden legs. One of these was a spare. So he pawned it for drink money. I wonder if my uncle is the same man that Timmy “Duckegg” Kirwan speaks of in his account of tenement life, when he says that he witnessed a man pawning his wooden leg so as to have money to buy drink. It is such an unusual story, that I feel it most likely was Jamsie. His wife used to hide the other leg to prevent him from going to the pub. When she wouldn’t tell him where it was, he would hop outside, hold on to the iron railings that surrounded the basement of the old house to get his balance right, before hopping across the Road to Levy’s Pub that was almost directly opposite. She would then have to bring him his leg so that he could get home again.

I had been born into a house with electricity, running water, a bath and toilet and gardens front and back. How my father managed to secure a house in what at that time would have been on the outskirts of the city I will reveal later. The tenements were something strange and frightening to me. The only lighting was by gas and this I found fascinating. I can remember seeing the “Lamplighter” doing the rounds on his bike and lighting up Mountjoy Street as he went from lamp-post to lamp-post. Years later, I would come to appreciate the song entitled, “The Old Lamplighter.” There was no lighting on the stairs in the house, and it was an eerie experience to have to walk up those stairs at night. It had a unique pungent odour that would immediately assault your nostrils as soon as you opened the hall door. The walls were painted with what was commonly known as “Red Raddle.” This was a strong mixture of lime and water with a colour added. It not only served to colour the walls, it also kept some of the vermin at bay, and it was very difficult to remove if you got it on your clothes.

My mother told the family that two maids had burned to death in the upper rooms in Dominick Street. Fires were not uncommon in these dilapidated old Georgian houses. My younger brother Bill swears that he saw the spectres of both of these ladies. But he firmly believes that they watched over him and kept him safe from the other ghosts that occupied the place. Because of the dark, and the likelihood of seeing something you didn’t bargain for, we would open the hall-door wide; then, using the available light from the street, try to reach the top floor before it closed. He held the record for getting there before the door slammed shut.

In those days, people were obsessed with Ghosts, Spirits, and the “Banshee.” The Banshee is an Irish word that translates into English as “fairy woman.” She is reputed to follow the old Irish families and forewarn them of an impending death. She is said to be a very old woman with long grey hair and grizzled features. Those people who claim to have seen her, state that she would sit on a window-sill or a nearby wall, close to the chosen family. She would wail and comb her hair as a warning.

Death would visit that family very soon afterwards. Alternatively, a picture would fall off the wall in the family home. The nail would still be there and the picture wire would be intact. This was another sign. I heard so many of these stories growing up, that I became frightened of the dark. A cold sweat would break out on my forehead and back as I walked passed certain dark alleyways or entered a dark hallway. Was it due to the fact, I wonder, that I was more attuned to the spirit world as a child than I am now? On a very odd occasion, I do get that eerie feeling in certain places, and I know when my family or close friends are in trouble. I am prompted to pick up a phone and call to see them when this happens. The dark doesn’t frighten me anymore. I out-grew that fear before I reached adolescence. In fact, I cannot sleep properly unless the room is dark. I came to realise, as I grew older that “Spirits” cannot hurt us. Except the ones you find in a bottle.

People used to entertain each other with ghost stories in those days. A good story-teller could keep a group enthralled for a whole evening. I remember on one winter’s evening, listening to one of the “bigger boys” telling a group of us gathered under a lamppost in Cabra West about the film he had just been to see. He told the story right from start of the film to the end. He was so good at it that we felt as though we had actually seen the film ourselves.

Although I do not place any credence in the stories about the Banshee, I cannot deny that on the night before my mother died, I heard what I thought was a dog howling. I was an officer in the Reserve Defence Forces at the time. I was on duty in Griffith Barracks (the same barracks where my father had been held prisoner, all those years ago) when I heard the awful mournful howling. I asked a colleague if he could hear it. He gave me a very puzzled look and said that he couldn’t hear anything. Next day, I had word that my mother had passed away.

It amazes me when I think of what the people endured while living in these rat-infested tenements. The unbearable stench, the single toilet, in the yard, one water tap and the “slop” bucket for nighttime use, which someone discreetly emptied next morning, or not so discreetly in some cases. It was not uncommon to find human excreta scattered about the yards. I can testify of this, for as young as I was, I can still remember this awful scene. Although, for some reason I don’t know of, there was a second tap and sink outside of the Ryan’s door on the third floor landing in No. 61. The death toll in these horrible places from diphtheria, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, and typhoid, etc. was at unbelievably high levels, particularly among the children.

Because of the filth lying about the yard, Mrs. Campbell would tie the ends of her washed bed-sheets across two lines hammock style, so that they didn’t trail on the ground and pick up dirt. One lazy “get,” (the word “get” is peculiar to Dublin people, while “git” is used in England,) who lived in the top floor back room, emptied his bucket out of the window. This practice was not at all uncommon. The contents included “brown trout” (excrement) and it landed in the sheets. While this may bring a laugh, it explains nevertheless, the mentality of some who lived in the tenements. It is hardly surprising then, that human excrement was littering the ground.

I cannot understand why my mother would move into such an awful place as Bolton Street. I can only assume that she fell into arrears with the rent and had to leave our house in Cabra. My father had already left home to join the British Army. Economic reasons forced him to take the pragmatic approach, like many other Irishmen before him. She must have been in a desperate situation, especially when she received the telegram informing her that he was missing in action. It wasn’t long before the younger ones in the family contracted “scabies” (which was endemic in the tenements). People used to blame returning soldiers for this. That might have been true after the Great War, when men had numerous diseases in the trenches, and returned home crawling with lice, etc. But it was not the case in this instance; particularly as the war was still in progress, and the men were still serving at the front.

The cure for scabies was quite radical. We first went to the South Dublin Union. This had been a workhouse that had been converted into a hospital for the poor people of Dublin. I can still remember arriving outside of the gates in an ambulance. The high walls and locked entrance were frightening to see, and we felt as though we would never see our mother again. Once there, we were assessed and stripped of all our clothing. They then shaved our heads and sent us to the “Iveagh Baths,” off High Street, where we got into a bath of very hot water and left to soak. Next, the nurses took us out, dried off, and painted us from head to toe with an ointment that burned like hell. Then they gave us a gown to wear that promptly stuck to the ointment, making life even more uncomfortable, before we returned to the hospital. This treatment was repeated a number of times in the succeeding days. I loathed the porridge that they gave us for breakfast. It was really thick, and there was no sugar to sweeten it or milk to thin it down. Occasionally they gave me a boiled egg. That was a real treat. But they flatly refused to serve this every day, when I asked.

While most tenement people were happy to move out to the new housing estates, it took some time before the tenement ethos moved out of the people. There were some who just couldn’t settle in areas such as Cabra West, and returned to live in a tenement. Cabra is approximately four miles from the city centre yet there were those who felt that this was too far away from what they had become accustomed to, and they just couldn’t take it. I do remember one family in particular whose mother died shortly after moving to Cabra West, blaming her death on the move and vowing to go back to “town” as soon as they could.

Professor Aalen of Trinity College states, with regret, that much of what’s been learned about tenement life has been filtered through the minds of outsiders looking in. He explains also that only through oral history can we reliably capture the life experiences of tenement folk. Since the tenements continued on into the late forties and to some extent, dare I say it, into the fifties, I trust that the experiences related here will help in some small way to fill the gap. For we, as a family, continued to visit our relatives in Dominick Street and Bolton Street.

When visiting my grandmother I noticed, as evening fell, that she would turn a tap on the wall at the side of the mantelpiece, above which projected a swan-neck shaped piece of pipe with a white globe, called a mantle, on the end of it. She held a lighted match to this and it lit the gas flowing into the globe, giving light. The globe was very delicate and if one wasn’t careful when lighting it, one could easily damage it and it would have to be replaced. When lit, its area of cover was very limited and there were dark shadows in the corners of the room. This, together with the light from the fire lent an air of mystique to the surroundings. On the one hand, it was warm and homely, and on the other, it felt ghostly. Only the spirits of the dead could live in the dark recesses of the shadows, and if you looked hard enough, you could see the misty form of those spirits beckoning to you. On more than one occasion, I felt the hair rise on the back of my neck and a quick shiver would run down my spine causing me to shudder. “Has someone just walked over your grave?” my grandma would ask as she touched my hair smiling benevolently.

“N… no grandma,” I would lie, putting on a brave face, averting my eyes, not wanting to get the reputation of a scaredy-cat.

Most of the tenants used buckets (mentioned above) for urinating into after dark. Perhaps it was because of the lack of light on the stairs. But I believe that it had more to do with their reluctance to go all the way down to the yard in the cold of the night. So they left the bucket on the landing. One night when I was with my father visiting my grandmother, I asked to go to the bathroom! “Sure use the bucket,” said my grandmother. I refused and so my father took me down the stairs in his arms to the toilet in the back yard. The dark didn’t mask the obnoxious smell and I refused to enter the cubicle. My father felt compelled to take me home to Cabra. Weeks later, when my mother was visiting, my grandmother told of my behavior, and asked how the little “Duke” was. My mother used that name for me from then on.

My family tried its level best to keep the yard and the toilet clean. But there was no way of controlling entry to the house or its surrounds, because the hall door could not be locked. Vagabonds could enter during the hours of darkness and they weren’t too fussy about where they defecated. Many of the tenement dwellers were sympathetic to the homeless (and there were lots) and allowed them to sleep on the landings and in the hallways at night. It at least gave them shelter from the elements. But it did nothing for the general hygiene, as it increased the occupancy of the house dramatically at night. Another good reason for using the bucket! This did not help the situation were the toilets were concerned. There was no agreed roster for cleaning the toilet either, and when it got blocked no one wanted to put it right. So it overflowed, and it would remain like that until someone finally gave in and unblocked it. All of this added to the risk of infection and this, coupled with the rampant malnutrition, resulted in a very high death rate.

The Campbell’s who lived on the ground floor of Number 61 were related to my maternal grand- mother. Johnny, the father, was a Belfast man and he had an accent that was a typical town centre rasping type. He missed nothing during the day because the door to his room was always open and he would sit there watching everyone who came and went. My father didn’t like him and only tolerated him because he was a Catholic. Many years later I learned why. My grandparents were not married, and Johnny Campbell had made the mistake of referring to my father and his sister as bastards. The use of that word by anyone in those days, whether true or not, was suicidal. Had he been a younger man, my father would have beaten the living daylights out of him. But he did warn him that he ran the risk of severe sanctions if he ever repeated what he had said. So we kids were told to ignore him, and not to go into his room, visiting. His wife was a lovely woman. Her name was Byrne, and she was warm and friendly, and always smiling. This was a common feature of tenement dwellers. Despite the desperate plight they found themselves in, there was always a smile and great humour. Perhaps this is where “Dublin Wit” was born.

Later in life I informed my father that I was going to research the family tree. He told me that I would discover certain information that would be best kept to myself. When I asked him to tell me what this was, as it might just save me save me unnecessary hours of work, he refused. I was to discover much later, that we certainly had a cupboard full of skeletons. It turned out that my grandmother had been married to the foreman of a brewery in Chapelizod, in County Dublin. He was violent and beat her regularly. She left him after he threw pepper in her face, before giving her a good hiding. Her eyes suffered badly as a result of this attack. Beating women was a common occurrence in those days also. The drunken thugs, whom they had the misfortune to marry, treated women appallingly. I cannot think of a more cowardly act than a man doing what this one did.

I was listening to a friend of mine delivering a lecture at a meeting recently and he stated, “The only time a man ought to raise his hand to a woman or a child should be to bless them.” How profound this statement is.

She met my grandfather, a gentle man, who treated her like a lady. He also looked the part and presented a very elegant figure in his bowler hat. It was the custom in those days for tradesmen and professionals to wear a bowler hat. This distinguished them from the labourer, who wore a flat cap. They fell in love and set up home together, despite the fact that she was considerably older than he. The implications of this are enormous, when you think about it. No one pays any attention to unmarried couples living together these days. But imagine how it must have been for them in the early part of the 20th century, particularly as my grandfather sang with the choir in Halston Street chapel, and this would have brought him into close contact with the clergy.

My father grew up a tough man as a result of his “illegitimacy” to give it the legal term that was used until recently. It was a bit like the song “A boy named Sue” sung by that great Country & Western singer, Johnny Cash. On more than a few occasions it was as the song goes, “the mud and the blood and the beer,” as he defended his and his father’s honour. His father was a coachbuilder, as mentioned earlier, and worked for the Great Southern Railways. He was also a very talented man with a wonderful singing voice. He won the gold medal at the Feis Ceol in 1900 (the year my father was born). I learned in later years that he had performed during the interval at the Abbey Theatre. He also sang on the same show as Count John McCormack, the renowned Irish Tenor, who had the title “Count” conferred on him by the Pope as a reward for singing at the Eucharistic Congress, which was held in Dublin in 1932. My grandfather was a Baritone, so there would’ve been no conflict with the “great man.” The Rotunda, which was originally the lecture hall of the maternity hospital, had been converted into a theatre in those days, and he performed there also. I can just about recall being at a show in the Rotunda with my parents. Afterwards, we called into Larry Sherby’s Fish & Chip Shop in Lower Dominick Street on our way home. Larry’s was a very popular shop and had booths where the customer could sit and enjoy the delicious fare that he produced.

The theatre was one of the treats that the tenement people looked forward to. They were to be found in what was commonly known as the “Gods.” This was the highest gallery, at the back of the theatre. My father decided to go the whole hog and bought seats for my mother and him in the stalls, which are the front of the house and on the ground floor. My mother had borrowed a large, wide-brimmed hat from a friend and she felt that she really looked the part of the moneyed lady. Friends in the “Gods” spotted her and began to shout down at her. When my mother tried to ignore them, they began throwing things at her. She was mortified at the time, but she could laugh at it years later.

Tenement life was the cause of my paternal grandfather’s death, through cardiac failure brought on by influenza, at the age of fifty-nine. This was not uncommon in the damp draughty conditions in which he lived. He managed to last a bit longer than my mother’s father however, who died as a result of tuberculosis, which was rampant among tenement dwellers. Billy Miller was a young sailor. At thirty-six years of age, he spent the last days of his short life in the hospital at the Pigeon House in Ringsend. It is said that Billy was a protestant, and that he came from a fairly well-off family. He met my grandmother, who was catholic, and they fell in love. His family, in a fit of pique, refused to attend their wedding. On the birth of their first child, so it is told, they offered to pay for the children’s education and see to it that they wanted for nothing as they grew up, if he would raise them in the protestant faith. He refused and they had no further dealings with him until he lay dying. They made it known that they wanted him buried in Mount Jerome, a protestant cemetery. He wasn’t having any of that, so he changed his religion and became a Catholic. He was a very good-living man by all accounts, and despite his protestant beliefs, would insist that the children attend confession on Saturday evening. They then had to come straight home afterwards, and they would not be allowed outside of the door until Sunday morning to attend Mass and receive Communion.

The Byrne’s were related to my mother’s mother. A little woman called, “The Nan Byrne” occupied one of the rooms. She read fortunes and had clients come to her from all over the city. Many of these were women, who travelled across town from the wealthy suburbs. I remember her very well. She had a Harpsichord in her room and she would let us kids play it whenever we came to visit her. She would ask Jim and me to go over the road to the Model Stores and get her supply of snuff. She let us sample it one day. We sneezed for ages afterwards and it cured us of asking again.

She was great fun and taught me the rhyme, “Holly and Ivy went to fair. Holly brought Ivy home by the hair. Holly and Ivy went for a glass. Holly brought Ivy home by the arse.” Another one went as follows, “A ch ch chee cauliflower sittin’ on the grass, up came a bumble bee and stung her on the a ch ch chee.” My mother roared laughing when I repeated them for her, but told me not to say it to my father, as he might get annoyed. He was very strait-laced in many ways, which puzzled me, considering what I was to discover later in life about my brother Paddy. My father had an affair after he had married my mother and Paddy was the result. In my whole life I never heard my father swear or use bad language of any description. He wouldn’t tolerate it under his roof and as a result, none of the family ever used foul language within our home. Nor, for that matter, did I ever hear him argue with my mother or raise a hand to any of us. He was unique among the men of his day. When he gave an order, you just carried it out and there was no dispute.

My Aunt Molly and Uncle Sean were my grandmother’s children by her husband. Molly used to look after us like an old mother hen. She would inspect our heads for “Nits,” and make sure that we were kept free of infestation. Sean was a quiet man and kept very much to himself. He worked for a potato merchant called Lambe Brothers. They had their yard in Mountjoy Street, just across from the house where they lived. Molly always insisted on being called Gaffney, her father’s name, despite the hard life that she had with him. After our family moved to England in the fifties, she became a patient in Portrane Hospital, her condition as a result of depression. On hearing this, my parents returned from England to visit her with the intention of taking her back with them. She refused and no amount of persuasion would change her mind. I accompanied my parents on that visit. It was heartbreaking to witness the mental decline she was suffering. She was surrounded by some seriously ill people, and a nurse explained that she ought not to be there. But try as we might, she just would not agree to go to England. We went away frustrated and feeling powerless by her refusal. Not many months later, we were back there again, this time to remove her remains to Glasnevin Cemetery. My uncle Sean had left the house in Upper Dominick Street and seemed to disappear without trace. Before he left, he disposed of all of the family records that were kept in a chest at the end of my grandparent’s bed. My eldest brother Paddy, finally found him in the Iveagh Hostel, off High Street where he died, to the best of my knowledge. Here was an example of the effects of the break-up of a closely-knit family. While my aunt and uncle had the rest of us around them, they were fine. But once the companionship and protection of the family was removed, physical and mental deterioration set in, finally resulting in death.

The Ryan’s were my mother’s sister Peggy, who was married to Michael Ryan. He had been a Sergeant Major in the Free State Army. He was in charge of the Detention Centre on the Curragh Camp in County Kildare and allowed a prisoner to escape. An Army court-martial demoted him to Corporal and he never got over it. His army buddies knew him as “Cushy File.” He was also quite a man for the ladies, so my aunt Peggy told me, and he didn’t care too much about who knew. That included her. He had the gall to bring one or two home with him, so she said. When he retired from the army, he worked as a labourer for a construction company. There was no health and safety organisation in those days, and on a very windy day he was blown off the scaffolding surrounding the “Bus Árus” (Central Bus Station). He fell several floors and cracked his skull, suffering a stroke shortly afterwards, that left his face disfigured. Safety nets were installed following his accident.

The company gave him a couple of hundred pounds and promised him a job for life if he kept it out of court. He agreed and they quickly found a way of getting rid of him anyway. He proceeded to drink all the money. My aunt didn’t get to see one penny of it. That’s how it was in the “Good old days.” Women were the property of their husbands. If my memory serves me correctly, they were no more than “chattel” according to the law, and they were treated as such. No one interfered between man and wife, no matter what the circumstances. If the woman went home to her parents, she was told to go back to her husband. “You’ve made your bed, now you lie in it,” she’d be told. Or, if she went to the priest and told him that she was denying her husband his “Conjugal Rights” because of his bad behaviour, she was refused absolution for her sins. Things have changed for the better, I am pleased to say.

One night, my aunt Peggy woke to find that the floor was on fire. Embers fell out of the grate, rolled across the hearth and set light to the tinder-dry floorboards. She woke “Mikie” and told him to get out of bed and get some water to put the fire out. He, in a half daze from sleep and too much booze, jumped out of the bed and stood on the burning floorboards. Letting out an expletive, he ran out onto the landing where their tap and sink were. When he didn’t reappear, my aunt called out to him asking what the delay was, as the fire was getting worse. “Eff that,” he yelled, “I burned me effen foot and I’m cooling it off.” He had his foot in the sink with the cold water running on it. She had to jump over the fire and get a pot, fill it with water while he complained that he needed it for his foot, rush back into the room and douse the flames. On another occasion, he complained to her about the “Hoppers” (fleas) that were in the bed. These were nasty little things that were brown in colour and sucked your blood when they bit. The more they sucked, the fatter they got. She said that everybody had them and she had killed some earlier. “Is that right,” said he, “well, there’s a few thousand at the funeral then and they’re all wearing hobnail boots.” He was quite the comic and his favourite song was, “The Ragman’s Ball,” which he sang at weddings and funerals.

Funerals could be more fun than weddings. There was a wake being held in one of the rooms. I’m not sure if it was when the Nan Byrne died. Anyway, the booze flowed freely; throughout the evening more and more people arrived to pay their respects. Pretty soon the room was full, so they moved the coffin into the corner to create more space. Someone had the bright idea to put the lid on the coffin and used it as a bar. It was done and a jolly good singsong got under way.

On another occasion at a different wake, the corpse was laid out on the bed and my grandmother tied a piece of twine around the deceased person’s foot and looped it over the lower bar on the iron bedstead. As the evening wore on and the visitors got more and more inebriated, she pulled the string. The leg of the corpse rose and the crowd, on seeing this, made a mad dash to get out of the room. One of the women broke her arm when she got jammed in the doorway by others rushing to get past her. Weddings and funerals attracted gatecrashers; smart-alecks looking for free drink and entertainment. This often resulted in a “ruggy-up,” (fight) and that proved to be even more entertaining. At one wedding, there were so many guests jammed into the room where the breakfast was being held that the floor collapsed and descended like a lift, and everybody wound up in the cellar.

After recovering from his injuries, my father arrived back home on leave from the British army. Seeing the conditions under which we were living, he went to visit an old IRA friend who worked in the housing department of Dublin Corporation. They arranged for us to move to the new scheme of houses in Cabra West. Now you know how we got the house in Old Cabra in the first place. Well, what are friends for?

Charles Darwin is quoted as saying, “A class will exist in the crowded poor districts, indifferent to insalubrities, indifferent to their surroundings, and sunk in ignorance. Even when change means improvement this class abhors it… …they prefer the old insanitary rookeries to the modern comforts of block dwellings.”

This may be true of some, but it would be unjust to generalise. All of the people who moved to Cabra were from the slums of Dublin. The vast majority of them were glad to be rid of the filthy hovels that they had been forced to live in through economic circumstances. They appreciated their new homes and set about improving the surroundings by cultivating their gardens, etc. I doubt if Mr. Darwin had studied the situation in Dublin. It seems as though he was referring to the tower blocks in London. That being so, perhaps it would have served all concerned better if he had understood that the people were fearful of being herded into vast ghettos. With so many living in close proximity to each other, the conditions would rapidly deteriorate to the same level, or worse, than what had been left behind. The Ballymun project is a clear representation of what I mean.

Bolton Street still holds certain fond memories for me, although I never realised until I read in a book by Kevin Kearns that it was famous for its brothels. During our time there, the Nazi’s bombed the North Strand. It was claimed later by them that it was a mistake. But that fooled nobody. Everyone thought that they were aiming for Amiens Street (now Connolly) Railway Station, where the trains ran north to Belfast, and the bombs overshot the intended target. Although I was only three years of age, I remember being taken to the air-raid shelter that stood in Kings Inns Street, close to our house. The shelter reeked of urine and excrement. Those who had nowhere else to relieve themselves used it as a toilet. I could see the beam of the searchlights as they scanned the sky, looking for the offending airplanes.

I had fun playing with my pal Sheamie Towel, who lived at the top of the house. We had been born on the same day in 1938, in the same hospital and almost at the same time, so my mother said. We would put the sweeping brush between our legs to simulate a horse, and race off like cowboys, round the corner into Kings Inns Street and shout at the women in Williams & Woods factory where my two sisters, Alice and Rosaleen now worked. I would shout at the workers “Hey that shook yeh, and the brown bread run ya!” We would hit the trail quick, whooping as we went, and shoot a few red Indians on the way home.

There was the time also, when workmen were resurfacing the road and laying tar. I noticed that every so often, a woman or a man would appear with a child, and one of the workmen would lift the child, and hold him or her over the hot tank. I got a hell of a fright thinking that they were burning the children. I called my mother and in shock pointed to what was happening across the street. “Ah! Don’t worry,” she said soothingly, “they’re only trying to cure them of the whooping cough.” Whooping cough was yet another disease in the tenements, and it was believed that breathing the fumes from hot tar would cure it.

So wherever there was road works, there would be a queue of people with their children waiting their turn to have them treated.

I remember also going to McLaughlin’s shop on the corner of King’s Inns Street, just across from our house. My mother had asked me to get a stone of potatoes. I had no bag and Mrs. Mac, who ran the shop, put the spuds into a newspaper for me. I struggled as I made my way out of the shop holding the parcel, cradled in my arms. I had my arms so high that the paper blocked my view and I forgot about the steel lamppost on the corner of the footpath. I walked into it and fell, spilling the potatoes all over the footpath. The people who came to help me were tut-tutting about the unkind mother who would send someone so young on such an errand. I was not more than four years of age at this stage. What would they know? One thing’s for sure… we kids from large families learned to stand on our own two feet at a very early age. My mother was the kindest and most loving woman you could meet. She was humble and meek, and has earned her sainthood as already mentioned.

One thing she wasn’t however was a seamstress. Someone gave her a length of cloth one day and she decided that she would make me a pair of pants. She wrapped the cloth around me, marked the end and cut the piece. She then joined the ends together like a skirt and stitched it. Next she found the middle of the piece and hand-stitched the back and front together for about three or four inches. This formed the openings through which I put my legs. In no time the stitching came undone in the middle and I was left wearing a skirt. At my age, I couldn’t have cared less. The problem was, when I sat down on the front step, my credentials were exposed for all to see because I had no underpants.