CHAPTER THIRTEEN

A NEW HOUSE IN NEWPORT

I had made it clear to Jo from the start of our relationship that I would be returning home as soon as an opportunity arose, and if she wanted to be my wife, she would have to get used to the idea of living in Ireland. The letter and the behaviour of the neighbours strengthened my resolve to seek employment back home, and I informed her of my intention. She didn’t seem to have a problem with this. If she did, she never said so. In the meantime, I began to scan the newspapers for new digs and noticed an advertisement for new housing in Newport Shropshire. The developer was having trouble selling the houses he’d built; he was offering to pay the deposit and help with the mortgage for suitable couples. The very next weekend, we drove the thirty-eight miles to Newport and had a meeting with the representative on-site. He was confident that we would qualify and we filled out the necessary paperwork.

A week or two later, we were contacted by the mortgage company, inviting us to come and pick up the keys for the house we had chosen. It would be a bit of a chore to drive that distance twice a day to get to work, but I was happy to do it. Within days of receiving the keys, we moved out of our digs. I had been attending a Judo Club for some time to keep fit and Reggie Bleakman, the black belt instructor with whom I had become friends, brought his van around to help with the move. Good people like Reggie, Mr. Balfry, and others proved to me that there were more decent English people about, than the other type. The difference, I found, laid in the degree of education, which the person had, or whether they had served in the armed forces. If they had, the odds were that they had Irish men and women serving alongside them, and they appreciated the contribution made by their Irish comrades. It amused me how naïve some of the English could be where the Irish are concerned. I remember being asked by a fellow office worker one day, if I missed the Saturday Night Fights in Dublin. He seemed awfully disappointed when I explained to him that this didn’t happen, at least not in the area where I was raised.

Newport was a growing village and the local people were concerned that there was little for the youth to do. I had a sign on the rear window of my car, advertising the Kyu Shin Kan School of Judo. I was approached by some of the local adults and asked if I would consider setting up a club in the village. A meeting was arranged with the interested villagers; soon afterwards, a committee was formed, and a club was founded. One of the members of the committee had a connection with a local army camp, and arranged for us to borrow their mats until such time as we could afford our own. We met in the parish hall and I arranged for Reggie to attend on Saturdays, to instruct the members. About three months later, we entered a number of members for “Grading.”

The first belt is white in colour, followed by yellow. The organisation doing the grading was different from the one I was a member of, so I had to grade along with the rest. As I held a yellow belt with the British Judo Council, it didn’t count with the British Judo Association, the local organising body. I applied to contest for two grades and was successful. The rest of our club entrants won their white belts, and we returned to Newport a very happy bunch. The army unit whose mats we borrowed were leaving to serve overseas and they donated the mats to us at no cost. We found Brian Evison, a local farmer who was a black belt, and he was willing to act as our permanent “Sensai” or teacher. He was a great character and the club progressed very well under his tutelage. The year was 1963; as we made our way to a demonstration evening in Shrewsbury, we stopped at a petrol station. The station attendant informed us that President John F. Kennedy had just been assassinated. We carried on to our destination with heavy hearts. That same evening Brian, our instructor, was demonstrating how to disarm an assailant wielding a knife. The opponent tried to be smart, and deviating from the rehearsed routine, he began switching the knife from hand to hand in the crouching position. Brian simply punched him on the nose, knocking him out. When he came to, he complained that that wasn’t Judo. “Maybe not,” said Brian, “but it was effective and that’s all that matters.” We had a great laugh about it later over a pint in the pub.

The next grading brought us further success. I was now a green belt, while the other members won yellow. The Shrewsbury Chronicle, the local newspaper, reported our progress much to the delight of everyone involved. Because of this, the club secretary approached the managing director of Audco Valves, Ltd., the company he worked for as an engineer and asked for financial help. His boss agreed to help, provided we fought under the title of Audco. Stan also informed me that one of the members of the company sports committee objected to my being the club captain, because I was Irish. He was promptly told that there would be no deal if I were removed.

At the following committee meeting, all members agreed with the proposal to accept the new name, and we became Audco Judo Club. The managing director was true to his word, and he arranged for the company to build a club premises on the company land. It was fully equipped with showers, etc., and soon became the focus of much attention in the village. The club returned his kindness by becoming County Champions within the next eighteen months. All was going well, and we trained five nights a week. We also had a weekend session every month with the Olympic Coach. All the clubs in the County gathered for this, and for two days training, all we paid was half a crown (two shillings and sixpence). A couple of my neighbours joined the club and Brian asked me to help with their instruction. I was demonstrating a throw and had one of them in front of me, as I pointed out the correct way to unbalance an opponent, and throw him. I had him under my point of balance, and was telling the rest of the class that all he now needed to do was continue bending, and the throw would be complete. Suddenly and without my telling him, he slammed me into the mat. Not being prepared, I landed awkwardly and as a result hurt my arm. Thankful that I had reacted fairly quickly, the damage wasn’t as great as it might have been. A couple of evenings later, one of my other neighbours approached me and asked how my broken arm was. I assured him that my arm was far from broken and asked where he got such an idea. “Oh, Colin across the road told me that he beat you on the mat at the club the other night, and that he had broken your arm.”

I showed him my arm, explaining what had happened and telling him that it was my fault I got injured and that I should’ve been ready for what he did. The following evening, I bowed in front of Colin. The bow in Judo indicates a challenge, and an opponent is not allowed to refuse. He nervously stepped onto the mat and as I took hold of his jacket, he asked me to go easy with him. “I’ll be as easy as you were with me,” I said as I threw him. He no sooner stood up than I slammed him down again… and again. When he was completely exhausted and could no longer carry on, I told him to be very careful with his tongue in future. I also warned him that I would be informing the neighbours about his performance that night. That was the last I saw of him in the club. He’d learned not to mess with a Sheridan.

Things were going so well that I decided to settle down in Newport. The locals had taken to the Irishman who was a member of the church choir, and who was also responsible for setting up their very own Judo Club. Then, as luck would have it I received a reply to a letter that I had written earlier to a firm in Dublin, inviting me to an interview. I found myself in something of a dilemma, having decided only a short time before that I would settle in Newport, now I had to make up my mind whether I should resurrect my plan to return to Dublin. I felt that there was nothing to lose by at least attending the interview.

By this time, I could run a printing machine and make plates, etc. The application that I had written was in response to an advertisement in the Evening Press, an Irish newspaper. The company was looking for a machine operator. As already stated above, I decided to attend and at least find out what the conditions were and what wages was on offer. When I presented myself at their office, I was given an IQ test and a mechanical aptitude test before the actual interview.

The general manager was friendly and we got on very well. He perused the results of the tests and stated that he was very happy with them. He was so pleased, that he offered me the job of Department Supervisor. He explained that the printing department was a new addition and that he needed someone who could get it up and running. He felt that I was the right person for the job. The wages started at £900 per annum, with the promise of a bonus at Christmas. This may seem very small money, but in 1964, it was a decent wages. It was £150 more than I was earning in my present job, and it meant that I could come home at last. I was given a month to wind up my affairs in England.

I returned to Newport, overjoyed at the prospect of what lay ahead and I could hardly contain myself as I told my wife what had happened. I would be sorry to leave Newport and the club and my friends; I realised that I had decided that I was going to settle permanently there. My wife was not aware of this however, as I hadn’t said anything to her. I probably would’ve stayed if it hadn’t been for the fact that her mother and sisters came visiting a short time previously and I overheard her mother saying that she would love to come and live with us. “Not on your life,” I thought, “That is never going to happen.” My wife seemed to be in favour of my taking the job. That’s what I thought at least, because she never raised any objections. So I went to see the local auctioneer and put the sale of the house in his hands.

Back to Dublin.

The month flew past and before I knew it, I was waving goodbye to my wife, my daughter, and our son, Eamonn Junior, who had been born in Newport and was now four years of age. I hated to leave them, but it was necessary to do so while I set about finding a house in Dublin, etc. The Judo club secretary was almost in tears when I told him that I was returning home. He felt that it might have had something to do with the comments passed by the person who didn’t want me as team captain. I assured him that it had nothing whatever to do with his racism, and that it had all to do with my wanting to live in my own hometown. I had arranged to stay with my sister May, who now occupied the old family home, and arranged to pay her what she thought was fair.

Before long, I was immersed in getting the printing department set up. There was much to do and it kept me busy late into the evening at times. The company was very efficiently run. Most of the staff was of Leaving Certificate Standard and the layout of the plant, (it wasn’t permitted to call it a factory,) was excellent. There was a first rate Restaurant (not Canteen) that was heavily subsidised. It meant that the staff could buy a hearty meal at a very reasonable price. It also took the onus off my sister, as she didn’t have to cook any meals for me except on Sunday.

I spent Saturday afternoon visiting housing developments, and soon found a beautiful four-bedroom house in the suburbs. It had a double garage and under floor heating and at £3,500.00, I felt that it was a bargain. I went to visit my Bank Manager and ask if he would be prepared to advance me sufficient funds for a deposit. He wasn’t too keen at first, but I convinced him after telling him that I had a house in England that was up for sale. He recommended a solicitor and after giving him the same assurances with regard to repaying the loan, it was arranged. I didn’t wait until the following Saturday, but arranged to leave work early enough to catch the sales people on site that Monday and secured the house.

I phoned my wife to tell her the good news but she didn’t sound very enthusiastic. “Perhaps she was tired,” I told myself. “After all, she has the two kids to look after.” “Any word from the estate agent?” I enquired.

“No, nothing yet,” she said. That was the usual comment as the weeks went by. The new house was almost ready and I was getting concerned that the builder would be looking for the rest of the deposit. So I decided to arrange to take a Friday off and travel over on Thursday night. I would go speak to the estate agent, and try to get things moving.

Imagine my surprise when he informed me that my wife had told him the house was no longer for sale. “I had a couple who were prepared to pay more than the asking price, because they had family living on the estate.” he said, showing a good deal of annoyance.

“Can we get in touch with them now?” I asked.

“It won’t do any good,” he said. “When your wife told me the news, I went knocking on doors and found a couple who had been thinking of moving and they decided to go ahead. The deal was done very quickly, so that’s that I’m afraid.”

“Could you put mine on the market again?” I pleaded, trying to conceal my frustration. I’m not given to using violence against women, but I felt as though I could wring my wife’s neck as I walked the mile or so back to my house. She flatly denied any knowledge of what the agent said. She was so convincing in fact, that I believed her. “After all,” I thought, “haven’t estate agents as bad a reputation as second-hand car dealers?”

I arrived back at work in Dublin early on the Monday morning, tired and worried. “What the hell am I going to do now?” I thought. There was nothing else for it but to bluff my way with the bank manager and hope that the house in England sold quickly. But somehow, I felt the opportunity wouldn’t come again so soon. It was time to bite the bullet.

The new house was ready, so I paid the remainder of the deposit and arranged to draw down the mortgage. There was nothing for it but to move the family over. I realised that this would add to the difficulty of selling the house in Newport, but I needed my family with me. In any event, the longer my wife stayed in England, the more difficult it would be to sell, if it was true that she had already put the estate agent off once. So I went to the bank manager again and borrowed the money to pay for the furniture removal. I was getting further and further in debt, and this began to cause me some concern.

I travelled over once again. Leaving on Friday evening, I arrived in Newport on Saturday in time to meet the removals people and help to pack our belongings for the journey home to Dublin. I had little or no sleep, but the excitement of the move and having my family with me again boosted my adrenalin to the extent that I didn’t notice any tiredness. I realised that the furniture would not reach our Dublin address until later in the week, and as my wife wanted to say goodbye to her family it was agreed that she would stay with them until I took delivery. By the following Wednesday, the truck had arrived outside the new house and I set about preparing the house for my family. I phoned my wife after arranging the flight from Birmingham, and told her that I would be at the airport to meet them on Saturday. All went well, and my heart leapt as I saw my family come through arrivals.

Almost as soon as I arrived back in Ireland to take up my new job, I phoned my old company commander in the Army Reserve. After visiting him in the barracks, he insisted that I sign on again. He was also a director of Ballsbridge Motors, Ltd., as mentioned earlier and when he heard that I needed a car, he kindly arranged to supply a ten-year-old Volkswagen at a very reasonable price. So I met my family, and with joy in my heart drove, them to see their new home.

The house was in immaculate order and as I proudly opened the hall door, I thought my wife would be as excited as myself. I was to be disappointed, however. She didn’t show any emotion. Matters were soon to deteriorate to a stage where I felt that I was on my own, as far as worries where concerned. The house in England sold eventually, but for much less than the asking price. By the time the agent and the solicitor got paid and the mortgage was cleared, there was very little left. I can’t remember what the actual amount, was but I do know that it didn’t go anywhere near clearing the debt in the bank. When I visited the bank manager to pay what money I had, and to explain the situation, I got no sympathy. He suggested that I sell the house and pay my debts. I countered with the suggestion that his idea wouldn’t help matters as there were still houses for sale on the estate and there was little or no chance of making a profit. I informed him that I was an honourable man, and that he would get paid if he would just wait a little longer. When he insisted on my selling, I told him that I would declare myself a bankrupt, and that he would have no chance of getting his money. His face lit up like a beacon, and I thought for a minute he was about to hit me. He demanded that I report to him on a weekly basis to discuss the situation. I asked my wife if she would consider getting a job to help out. She was rightly concerned as to who would look after the children. I explained that my mother and father wanted to return home, and that they could take care of the kids. She agreed and promised to start looking for work straight away.

While all of this was going on, I was trying to run my department at work as efficiently as I could. I was working long hours and getting nothing extra in my pay packet because I was a staff member. Being a member of “staff,” in my opinion, is a way of being screwed by the employer. My apprentice had more money in his pay packet some weeks because he wasn’t staff and got paid for overtime. I had no complaints, however. My belief, rightly or wrongly, is that if one agrees to take a job, knowing what the terms and conditions are, then you just get on with it.

Bombs and Bums and Buggers with Guns.

I was also progressing at a rapid rate in the army reserve. My corporal stripes had been restored within weeks of my signing on again, and I was nominated for a sergeant’s course almost immediately after that. Time was flying by, and at the end of summer of 1964, I had my sergeant’s stripes up. Earlier in the year, I had been a member of the most successful 81mm mortar team ever. Our score had been higher than anything previously achieved in either the regular army or the reserve. During the course of the shoot, there was a misfire in the number two gun. A bomb was jammed in the tube. The gun controller called out misfire, and both gun crews quickly ran for cover in accordance with procedure, in case the bomb blew up. After waiting the required time with nothing happening, the gun crew are then obliged to disarm the gun. The crew approached the gun, and gently undid the collar-locking device. This frees the barrel and allows it to be turned so that the number two on the gun can raise it. By so doing, the number three puts both hands in front of the barrel opening, so that he can catch the bomb as it slides out. This is a highly dangerous manoeuvre, and an officer must supervise it. In this case, it was the duty of the regular training officer to oversee things. He stood there behind the gun crew as Private Willie Phelan raised the barrel but nothing happened. The bomb was stuck fast. So Willie gently shook the barrel from side to side. Still nothing happened. So he shook it violently saying, “Move, yeh f….r.” On seeing what he was doing, the officer retreated backwards at a faster rate than I’ve seen some guys run. The final shake did the trick, the bomb was dislodged and the number three caught it before it hit the ground. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Here we were on “Cemetery Hill,” and if the number three hadn’t caught the bomb, there would have been bodies blown all over the place. The handling of the misfire was noted and the crew complimented for their efficiency. The officer got one hell of a slagging afterwards, and didn’t live it down for years afterwards.

The following year, 1965, around the same time of the year, I was back in the Glen of Imaal, this time as a sergeant. We arrived in Coolmooney Camp on the Saturday afternoon and offloaded the ammunition, putting it in the camp magazine. After tea, we were back in the magazine priming the bombs in preparation for the shoot next day. This involved taking the detonators from a box, setting the fuse on instantaneous, and screwing the fuse into the top of the bomb. This might sound dangerous and it is, but not as much as one might think. The bomb is detonated when it strikes the ground. It is shot from a tube that is set into a base plate. After reaching the zenith of its travel, it falls back to earth and explodes when it hits the ground. Everything within a hundred-yard radius, depending on the type of ground that it lands on, is in danger. The idea behind it is to drop a pattern of these on an enemy position, causing death and terror. So unless someone drops the bomb while it is being primed, there is no danger. We made sure that the bombs stayed in their cases while the priming was taking place, as a precaution. The only other way they would explode is if someone hit the fuse with a hammer or something similar, and none of those present had a death wish. So there was not a lot to worry about when a corporal lit a cigarette while he worked. I told him to get the heck out of the magazine anyway, as the younger private soldiers were about to panic. Besides, he hadn’t asked permission to smoke. He left the force not long afterwards and joined the Gardaí. The last time I met him he had been promoted to sergeant in the motorcycle section. He’ll be in no danger there, as long as he doesn’t light up while riding the bike.

Our job was finished within the hour and I reported to my commanding officer that all was in readiness. He was pleased that it had been done so quickly. He informed me that one of the senior officers was returning to Dublin shortly. As my wife was due to have our third child very soon, he thought that I might like to spend the night at home. The colonel would be returning to camp next morning, and he would give me a lift back. I thanked him for his kindness and accepted the lift with gratitude. I met the colonel shortly after that, and we headed out of the camp in his car. Just as we turned left out of the gate to head for Dublin, we passed a group of four hikers. He stopped the car. “You’d better tell those lads that we’ll be dropping high explosives into the Glen tomorrow and they need to get up over Table Mountain tonight for their own safety.”

“Right sir,” I said and got out of the car, calling to the hikers. They stopped and turned round to face me. As I explained the situation, I realised that one of them was an electrician who was carrying out maintenance work at the plant where I worked. “Hi,” I said smiling.

“Hello,” they replied…

“Ah, howareyeh?” said the electrician, “I didn’t know that you were a member of the Free Clothing Association. What are yeh at.” I explained about the shoot and ignored his smart-ass remark. “No problem and thanks for the warning” said the one who appeared the leader of the group.

Back on camp next morning, I thanked the colonel for his kindness, and set about getting the teams ready for the shoot. Everything we needed was loaded onto trucks and we headed off to Cemetery Hill, which would be our firebase. The hill is so named because of an accident that occurred there during the Emergency. An officer was demonstrating how to arm a landmine to a platoon of soldiers who were seated amphitheatre style on the side of the hill. He did something wrong and the mine exploded, killing him and most of those seated nearby. The remains of many of them are buried on the top of the hill. The graveyard acts as a reminder to all of how careful we need to be when handling weapons or explosives.

The sun shone in a cloudless sky that morning, displaying the beauty of our surroundings. Mother Nature was at her best as she raised the curtain of early morning mist from the land to expose the exquisite beauty of the scene set out before us. The sun warmed our bones as it took the chill out of the air, promising a day that would be remembered with fondness by all who were privileged to witness the sight before them.

It seemed that the sacrilege of doing this on Sunday would be compounded by the assault that was about to be perpetrated on this beautiful scene. I was reminded of similar days in Kilbride Camp in the Dublin Mountains when, during a break, I sat on a rock in the rushing waters of the river that runs through it. I was prompted to pen the following verse as I looked at discarded rubbish that was polluting the crystal clear water.

I wonder if man will ever see

That a river, running wild and free

Is far more beautiful than he

Or, does he know, and through jealousy

Pollutes it.

Back at work on Monday morning, the electrician approached me. “Your shooting wasn’t very good,” he jibed.

“What do you mean?” I asked, ignoring the mocking attitude he had adopted.

“Me and the boys were sitting on the side of the hill opposite, watching you through binoculars and your bombs were landing all over the place.”

“If you knew anything about mortar fire, you’d know that the whole idea is to drop them in a pattern on an area, so as to catch the enemy as he tries to run in any direction. Anyway, I thought you and the boys were supposed to be heading over the mountain into Glenmalure?”

“Oh yeah we did that last night and spent most of the night stripping and assembling the Thompson Sub-Machine Gun in the An Oige Hostel. We told the rest of the boys there about the shoot and it was decided to watch how you did.”

“What boys are you talking about?” I asked.

“The IRA boys, who else?”

“Would yeh get lost,” I said, in as derisory a tone as I could muster. “The IRA are dead and gone, so you’re just shooting your mouth off… right!”

“You can mock all you like,” he said, taking a step nearer, “but we have a surprise in store next year for you and your guys, just wait and see.”

“Oh, give over will you?” I said, half laughing. “You lot weren’t up to the task in the 50s and you won’t have any success in the future. So what’s the big surprise, or are you just talking through your hind-quarters.”

“We’re going to blow Nelson Pillar down, and that same night, we’re going to wipe out the high-ranking army officers and politicians. So how will you like taking orders from us in the future?”

“Would yeh ever go and get yourself seen to?” I said mocking him, “You’re raving and you’d best see a shrink before you lose the run of yourself altogether. Now get lost, I’ve got work to do.”

“We’ll see,” he said as he walked away his face red with anger.

I thought long and hard on what he’d said to me as the day wore on. The business about Nelson certainly tied in with what a school friend had said to me ten years previously. He was a member of Sinn Féin, and I hadn’t put any store by what he’d said at the time. But now it was being repeated and I supposed that there had to be some truth in what I’d just heard. I want to make it clear to the reader that I didn’t like the idea of a British Admiral looking down on us from a pillar in the middle of the main street of our capital city. To be honest, I wasn’t too concerned about whether they blew up the pillar or not. But the rest of it concerned me very much. We had experienced the horrors of a civil war once already, and the legacy was still alive to a large extent in the 1960s. There had been no contact with my father’s uncle, or his side of the family, since that time when he was part of the escort, which took my father to the train that would take him to prison during the Civil War. I didn’t want to see that happen to anyone else’s family. So I decided after pondering on it for three days, to phone my company commander and discuss it with him. I was at pains to point out that I felt what I’d heard was bravado and may not amount to anything. He agreed and asked if I would be in barracks the following night for the usual parade. I confirmed that I would, and he said we’d talk further then. Feeling a bit more relaxed I got on with my work.

The next day, Thursday, seemed to fly by. There was lots of work on and we were busy all day. The only break in the schedule was a visit from the General Manager, who told me that a new girl would be starting work on Monday and that she lived on the same estate as myself; he asked me if I would be willing to give her a lift in the mornings and drop her home in the evenings. I agreed and he thanked me. I didn’t say anything to my wife when I got home. It slipped my mind and I didn’t think it was important anyway.

When I arrived in barracks that evening I was met by the Company Sergeant, who asked me to report to the CO’s office. The place where we paraded (gathered,) for training was the top floor of a very large three-storey block. It was a total shambles when we took it over, with paint peeling off the walls and generally filthy. The post-colonial thing was very much in evidence. A chapter in the Crane Bag talks about the neglect that happens when a country throws off the yoke of oppression. The contempt held by the newly freed people for the buildings, etc., of the oppressor leads to complete neglect and vandalism to a large extent. This is because the new occupiers don’t view the buildings as being theirs. In our case however, the unit got together at the request of the CO and stripped the walls and woodwork and painted them. One of the other sergeants in the unit was an accomplished artist and he painted the cap badge on the end wall of the billet. It was four feet in diameter and done in black and gold on a cream background and it looked magnificent. We were very proud of what had been achieved, particularly as it was done in our own time. The CO of the barracks tried to take it off us when he saw it and give it to the regular unit for their use. But our CO was made of sterner stuff and told him where to go.

I knocked on the door of the office and waited until I heard the CO invite me in. He stood behind the table that acted as his desk in that dingy place. It had an army blanket thrown over the top of it to mask the damaged surface. A single light bulb with no shade hung on its original flex from the very high ceiling, casting shadows in the corners of the room. The only thing that lent any cheer to the surroundings was a lighted fire in the large grate. Standing next to the CO was a tall man, wearing a greatcoat over his uniform against the chill of the night. I noticed that he had what we other ranks referred to as “custard” on the peak of his cap. “Ah… hello sergeant,” said my CO. “This is Colonel Fitzgerald, the Brigade Commander. He’s interested in what you told me on the phone yesterday.”

Before he could say any more, the Colonel stepped forward as I lowered my hand from the salute I had just given both of them. He held his hand out and took mine. His hand was bony, but his grip was firm. There are some people who are the wrong shape for a uniform. No matter how they try not to look like a sack of potatoes, they just don’t succeed. Not this man. He was tall and slim and the uniform hung on him as though it had been painted on his frame. He held his head high and looked every bit a soldier.

“Would you mind repeating what it is you told the Commandant?” he asked, while looking me straight in the eyes.

This man could read what is imprinted in the back of your brain, I remember thinking to myself. I told him the story and how it came about that I should be talking to an alleged member of the IRA. He was particularly intrigued when I told him that a school friend had told me practically the same story ten years earlier, all except the bit concerning a possible coup d’état.

“You’re probably right about this fellow being a braggart, but I’ll report it to the Garda Special Branch anyway and we’ll see what they have to say.” He thanked me and I saluted and went about my duties.

During the next week or so, I set about contacting my parents and arranging for them to return home. I got their room ready and awaited their arrival. My mother’s face lit up when she saw me waiting on the pier at Dun Laoghaire. “Howareyeh Ma?” I asked, “Did you have a nice trip? Hi Da, are you well? Was the journey alright?”

“Yes,” they both replied, not showing any sign of the tiredness that I knew from experience was a feature of travelling by boat and train. We headed for home and after they had settled in, I invited my father to accompany me to the local pub for a pint and a chat.

“It’s great to have you home, and I’d just like to ask a favour of you, if you wouldn’t mind,” I said, as we sat down with our drinks.

“What’s that?” he said with a puzzled look on his face.

“I want you to promise me that if a problem should arise, no matter what it is, that you will ask me down here for a pint and tell me. There may never be a need to do this, but I’m just making sure that you know there is nothing that can’t be sorted out over a pint. It’s possible that there might be a disagreement with two women in the kitchen, who knows, but whatever it is, we can resolve it by discussing it. Will you do that for me?” He agreed and I felt that all would be well, as I trusted him to keep his promise. Next day was Saturday, and I took them to visit the rest of the family who were living in Cabra West, Finglas, and Dorset Street in the city centre. Everything seemed to be working out fine, and I returned to work on Monday, happy in the knowledge that at last my wife had the babysitters that would allow her to find a job. I could at last see some light at the end of the tunnel. My job was going very well and I was happy that I had been able to help my parents in a small way.

The company commander called me into his office when I arrived in barracks the next day. We paraded on Sundays from eleven until one o’clock, and on Thursday evenings from eight until ten. “I’ve just had word that a potential officer course will be starting soon, and I want you to go on it.”

“Thanks sir, but I’m happy as a sergeant,” I said.

“I’m not effen asking you, I’m effen telling you,” he said, while blowing a stream of smoke from the long draw that he had just taken on his cigarette. “There’s an interview in Army Headquarters on Thursday next at eight… be there.”

“Right sir… and thanks again.”

“Here, have a fag,” he said holding out the packet of Player’s.

“Thanks, but I don’t smoke,” I said politely.

“Have an effen fag,” he insisted. So I took one, wondering if this was a test of my obedience. If it was, he needn’t have worried. All he had to do was give me an instruction and I would carry it out. He would have known that anyway. We puffed and made small talk until we’d finished our cigarettes and I returned to my duties once again.

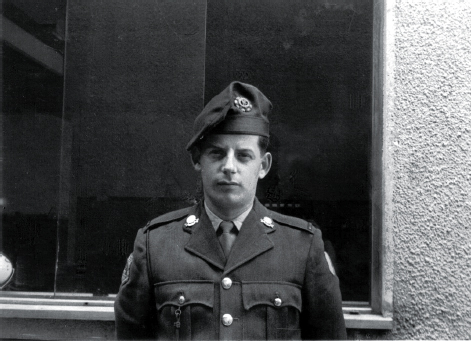

My parents were proud to see me in uniform. My mother said that she was delighted to see that at least one of her sons had put on the “green jacket” that her husband had left off. This was a reference to his IRA service. I got the camera out and had my wife take a photo of me with me parents standing in the front garden. They were delighted to hear that I was nominated for an officer course and wished me well for the upcoming interview. Life was great, I thought, and it would be a whole lot better if my wife could get a job and help out with the finances. But she kept claiming that she was being discriminated against, because she was English. I found that hard to accept. Most Irish people were inclined to go out of their way to be polite to visitors. But she insisted that this wasn’t the case. Then one evening when I arrived home, I noticed that me mother had been crying. I asked her what was wrong, assuming that she’d had a disagreement with my father. She said that she had a cold. I didn’t want to pry, so I accepted her explanation, though I knew in my heart that a cold wasn’t the problem. I thought that there had been an argument with my father and I didn’t want to interfere.

The interview at Army HQ was in front of a panel of senior officers, and it went so well that the Battalion CO rushed back to the barracks to inform my Company CO that I had taken first place. There was great jubilation. Anyone would’ve thought that I’d won a major battle. But learning later that my performance would reflect on both of my senior officers, I understood their reason for celebrating. It gave me great satisfaction also, I have to admit. The course would start in a couple of weeks and I looked forward to it with great anticipation. I was to learn from my boss later that one of the senior officers in the battalion was a close friend his. They apparently compared notes on my performance, both in the force and at work. My future seemed assured.

Back at work the following day, one of the male staff came into my department and asked if I had seen the new girl in quality control. I said that I hadn’t, and he said just wait and see… she’s a beauty. There was a tea break at ten o’clock each morning, and I promised I’d check the QC department on my way to the dining hall. Ten o’clock came and I headed for the dining hall, via Quality Control. I saw a new girl and wasn’t particularly impressed. She was nice enough, but not someone that I’d be excited about. After the break, the same guy came over to my department and asked me if I’d seen the new talent. “I did and I’m not impressed,” I said in answer to his question.

“You’re one fussy bugger,” he said, and disappeared as quickly as he’d come.

Later however, as I made my way back from lunch, I realised why he was so excited. Two new girls had started, and the one he was talking about was standing near one of the folding machines, surrounded by six guys who were behaving like dogs in heat. I decided that she needed rescuing and poked my head between two of the guys and asked, “When?”

“When what?” she asked smiling.

“When you’re finished with this lot, call over to the printing section and I’ll tell you the rest.” I had just reached my desk when she appeared beside me.

“So do you have something to say to me?” she asked. I must admit that I was aroused just to be standing beside her. Her name was Linda and she was seventeen, I learned. “Is that short for Belinda?” I asked.

“No, just Linda,” she said.

“Never heard of it before. It’s beautiful.” She seemed amused and we talked rubbish for the remainder of the lunch period. “Talk to you again,” I said as the bell went to signal the end of lunch break.

“Looking forward to it,” she said, as she walked away. For the rest of the afternoon, I kept getting phone calls from the other guys, calling me a dirty so and so. How people’s minds work! If there’s nothing to talk about, they’ll make things up. We were very busy over the next week or so, and things soon quietened down again.

When I got home, I noticed once again that my mother was crying, and she tried to hide her tears from me as I walked into the sitting room. “What’s the matter, Ma?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s nothing,” she said.

“Are you having trouble with me Da?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“Is there anything that I can do?” I asked.

“No,” she said. So I let it go again, not wanting to interfere. Little did I know what was to come.

The following day, I got a visit from my eldest sister Alice, accompanied by May and Dick, the two older siblings. Dick was fired up and ready for a fight.

“What going on with me Ma and Da?” he demanded. I could see that there was trouble afoot from the faces of all three, especially as Alice lived in England.

“Just hold on a minute,” I said to Dick. “Come with me and let’s have a chat.” I walked out into the hall and up the stairs. When we reached my bedroom, I told him that he could have trouble if he insisted, but first tell me what this visit was all about.

“Right,” he said. “Are you telling me that you know nothing of the way that your wife has been treating me Ma and Da.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “She’s been giving them a terrible time since they arrived, and your daughter keeps asking them when are they going home. Now, I know that she’s too young to make that up herself. She’s obviously been put up to it. Me Da opened a letter addressed to J. Sheridan, thinking that it was for him. When he discovered that it was for Jo, she abused him terribly over opening private mail.” There was a whole list of things he told me that left me dumbfounded.

“You can believe me or not, but this is the first I’ve heard of any problems.” I told him about what I’d asked my father to promise.

He knew nothing of that, of course. “We’re here to take them away,” he said, “They’re going back to England with Alice tonight.”

“What?” I said, “They can’t do that. Let me talk to them.”

“It’s too late,” he said. “They’ve already made their minds up.”

“Right,” I said, “I’m going for a pint.” I was fit to be tied as I sat in the bar sipping my beer, not knowing what to do for the best. I decided to try to talk to my father, and at least ask him why he didn’t keep his promise.

“I didn’t want to interfere between man and wife,” he said.

“I wouldn’t have considered it interfering,” I said. “What’s going to happen to my mother? She’s not able for this.”

“I’ll look after her, as always,” he said. “Won’t any of the family put you up here in Dublin? You can’t be taking her back to that awful place.”

“We asked, and the answer is no, so Alice has a house for us, next to hers in Oldham.”

It had only been two months or so since they had arrived. Now in this cold October, they were heading back to England. I was devastated, particularly when I thought that they didn’t even get to spend Christmas in Ireland. The seeds of separation between my wife and myself had been sown much earlier, and now they were blossoming. It took all of the control that I could muster to keep from exploding into a rage. Again, my wife denied everything. No, she hadn’t prompted our daughter to ask her grandparents when were they going home. No, she hadn’t verbally abused my father for mistakenly opening her letter. No, she couldn’t get work, because she was being discriminated against. Finally, no… she no longer wanted any sexual relations with me because she had, “done her duty.” If she felt that way, she said, she would let me know and as we were practicing Catholics, any contact in future would have to be at the safe time of the month. Love and all that flowed from it was a spontaneous thing, I told her. I wasn’t about to be controlled in that way. I couldn’t compartmentalise my love life, in spite of the disciplined way I ran my job and behaved in the Armed Forces.

I arrived in work on Monday, mentally bruised and quietly seething with anger. No one would’ve known from my demeanour, however. I was good at disguising my feelings and in any event, all of what had gone on was private, and I didn’t believe in bothering others with my personal problems. As things turned out, I found myself standing next to the new girl, Linda, in the queue for lunch that day. She seemed as pleased to see me, as I was to see her. After some small talk, I asked her if she liked Chinese food. Chinese Restaurants were new to Ireland at that time and they were regarded as a novelty.

“Yes,” she said.

“Well, how would you like it if I took you to one?” I asked, fully expecting her to laugh it off as a joke. After all, why would a beautiful girl like her be interested in a guy ten years her senior, when she could have the pick of the crop.

My heart leapt in my breast when she said, “Yes.”

There were others around us on the queue, and from the looks that we were getting; I thought I’d better end the conversation good and quick. “I’ll ring you later,” I whispered. We had reached the top of the queue anyway, collected a tray, chosen our lunch, and moved on. I could hardly wait to finish lunch, as I felt that everyone in the dining room was looking at me. Back at my desk, I wondered as I eyed the telephone, whether she would reject me if I made the call. She’ll have taken it as a joke, I kept telling myself. Don’t ring, you’ll only make a fool of yourself, my inner voice kept saying besides… you’re a married man.

I resisted the temptation and congratulated myself on my self-control. Just as well that I did, because the word had got around about our conversation, and she was being watched like a hawk watches his prey. In fact, one of the older male staff came to me during the course of the afternoon and reminded me of my obligations as a married man. I had seen him in the local church a number of times when I’d called in to offer a prayer before starting the day’s work. He reminded me about this, and pointed out the consequences of what I was doing. I thanked him for his concern and informed him that I wasn’t doing anything except having a laugh with a young woman that I admired. I reminded him about the scandalmongers and what their fate should be, according to the Bible. I also told him as politely as I could to mind his own business.

When I got home that evening, I found my wife sitting by the fire, staring into the grate. The breakfast dishes were on the draining board unwashed, and there was no dinner prepared. It was usual for me to get up very early and prepare breakfast before I left for work. I saw to it that the kids were fed, and that my wife got some tea and toast in bed. The unwashed dishes had now become the norm. But no evening meal was a new departure. When I enquired of my wife why this was so, she said that she had been too busy. Now, I knew that it couldn’t have been from cleaning the house, because that was my job on Saturdays, (shades of her father in Birmingham). The children were well-behaved so it couldn’t be them. She obviously wasn’t interested, and she constantly reminded me that we didn’t have money problems in England, and that she would easily find a job if we were to return. I must admit that I gave it serious thought. The bank manager was at me again, too; and the strain of it all was beginning to wear me down.

I had finished the potential officer course and though I’d passed it, I was somewhat disappointed with my performance. I finished eighth in a class of ten. The pressure that I was under was affecting my performance, and I realised that I needed to keep things together. Whatever about my hobby, and that’s what the reserve was, in effect, I wasn’t going to allow it to affect my job. So I took whatever steps I needed to in order to keep on top of things.

There was free medical cover available to all of the employees at work. The doctor would visit twice a week, on Monday and Friday. I was running a temperature, and decided to pay him a visit. My head felt is if it was about to explode. After checking me over, the doctor asked why I had come into work in the first place. I told him that a simple cold wouldn’t keep me away. He said that it was anything but a cold, and told me that my temperature was dangerously high. I was ordered to go home straight away, get into bed, and call my local GP. I reported to my immediate boss and then to the General Manager. They insisted that I leave for home immediately. By the time I got there, I was sweating profusely, and my chest felt as if it had a ton weight on it. My GP called, and confirmed that I had a bad dose of pneumonia. He was quite concerned, particularly when I told him that I had had pneumonia previously. He visited me every day for the next week to make sure that I didn’t need to be transferred to hospital. I was completely run down, and to add to my woes, I had an abscess on my elbow, and to make things even worse, I got shingles.

During the second week, the young lady that I gave a lift to every day called to the door enquiring about my health. It was a lovely sunny Saturday and I was sat on the settee in the living room watching the television. My wife showed her in with a look of distain on her face. The young woman apologised for disturbing me and told me that her mother, who was waiting at the bottom of our driveway, insisted that she call. It was the least she could do, in return for my kindness in giving her a lift, she said. We talked only briefly and I informed her that I would be off work for at least another week. Following her visit, my wife went into a jealous huff. When I enquired as to what was bothering her, she informed me through gritted teeth that she knew about me and the other woman. One of the neighbours, whose house faced up the road had seen me pick the girl up and drop her off each day, and she reported this to my wife.

“All I do is give her a lift,” I explained, “and that was at the request of my boss. She lives on the estate. Don’t you think I’d be more discreet if we were up to anything?”

“You weren’t discreet when this was taken,” she said, handing me a photo. I almost had a relapse. It was a picture of me sitting beside the secretary from work in Birmingham. It was taken at the last office Christmas lunch. We were sat beside each other, and I was looking at her. Both of us were obviously enjoying whatever remark had been made, but that’s all. Where she got the photo from, I will never know. I still don’t know to this day. No amount of explaining on my part would mollify her. Perhaps I should’ve told her about the lift right at the start. But it just didn’t strike me as important. Besides, I was also picking up a woman who lived on a nearby estate. When I told her this it only made her worse. She began harping on about returning to Birmingham and how much better off we were over there. I told the two women about her comments, fearing that she might be at the top of the road one morning, making a show of herself. They immediately dropped me and found other means for getting to work. It caused me considerable embarrassment when my boss approached me and mentioned it.

It was three weeks before I was fit enough to return to work anyway. The abscess that was followed by shingles had followed the pneumonia. Just as I thought I was clear, I went for a drive on Friday of the second week at the doctor’s suggestion, and struggled back to his surgery with pleurisy. My boss was very understanding, and insisted that I was not to worry about missing work. It was nice to have a friend. Particularly as I was feeling so isolated. My wife was of no help, and I couldn’t talk to my family. They didn’t want to speak to me since my parents went back to England. If I am totally honest, I didn’t want to speak to them either.