15

A Mite o’ Dickerin’

EVERYTHING worked out fine Friday morning. Philip went to Medford Square to order the lumber and get the paint, and Mr. Durant said it would be all right for him to work in my place. As soon as school was out in the afternoon Grace met me at the streetcar line, and from the way she acted anyone might have thought she was my mother. She had on her high-heeled shoes, and her Christmas gloves, and she was carrying Mother’s handbag over her arm as if she were a grown-up lady.

All the way to Sullivan Square, Grace kept scolding at me because I’d forgotten to shine my shoes. And she wanted to see if my fingernails and ears were clean. I tried to tell her those things didn’t make any difference when we were only going to dicker with a Chinaman and buy irons, but she wouldn’t let me alone. “Hmmmf!” she sniffed. “That’s what you think! Maybe you didn’t know that Mother gave me Uncle Levi’s address, and if he takes us to a restaurant for supper, I don’t want to be ashamed of you.”

“Well, you won’t have to be,” I told her. “If you could see the daub of paint on the top of your own ear you wouldn’t worry so much about how I look.” That was the only thing that kept her from scolding at me clear to Essex Street. She was so busy peeking at the little mirror inside Mother’s handbag and scratching paint off her ear that she didn’t have any time to pester me.

Mr. Haushalter was right when he told me the streets in the Chinatown district ran all cattiwompus, and even if we’d had a compass we couldn’t have gone straight to the eastward. So we kept turning corners till we found a street where all the stores had Chinese writing on the windows and signs. There was a Chinaman standing in the doorway of nearly every one, hiding his hands inside his sleeves and jabbering at us as we looked in the windows.

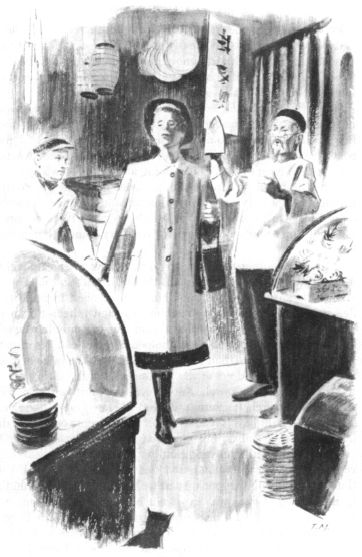

We were sure we must be in just about the right place, but we didn’t see any store with new irons in the window, so Grace took Sam’s note out of the handbag and showed it to a Chinaman who was standing in the doorway of a secondhand store. From the way he’d been jabbering I didn’t think he could understand a word of English, but he could certainly read Chinese. As soon as he glanced at Sam’s note he opened his door and bowed us in as if we’d been a king and queen. Then he went to the back of his shop, rummaged around for a few minutes, and brought back an old iron with a little crack down one side. He held it out to us, with his thumb over the crack, and said, “Velly good. Four dollar.”

Grace shook her head and said, “No, that one’s no good; we want a new one.”

Instead of taking it back, the Chinaman held it farther out toward us and said, “Sree-nine’y-fi’e.”

“No,” Grace said, “we don’t want it. We want a new one.”

The storekeeper looked at her blankly, then said “Sree-nine’y.”

“It’s no use,” Grace said to me. “He hasn’t anything but secondhand junk in here; let’s go somewhere else.”

If that Chinaman couldn’t understand every word she said, he certainly knew what she meant. “Jus’ a minute, jus’ a minute,” he said, reached under his counter, and brought up a brand-new iron, just like Sam Lee’s. He pushed it across the counter toward us and said, “Six dollar,” just as plainly as I could have said it.

For a minute I was sort of stumped. I’d expected him to say, “Four-fifty,” and I was all ready to say, “One-fifty,” but with him starting at six, I didn’t know just where I ought to begin. Grace helped me a little bit by giving the pocket of my coat a twitch. “No! One dollar,” I said.

It must have taken at least half an hour for him to get down to four-fifty, and I must have lost track somewhere along the line; I was already up to a dollar sixty-five. Grace twitched my coat pocket again, then walked away from the counter where she could whisper to me. “You’re doing all right,” she whispered, “but be careful of him from now on. Once he made you go up a dime when he only came down a nickel, and if he does it many more times we’ll get stuck. It’s all right to go to three twenty-five, but don’t you go any higher. We’ll try some other place first.”

It took us another half hour to do it, but we ended up right on three twenty-five. I’d fallen a little bit behind, so that I was at three twenty-five when the Chinaman reached three forty-five, but when we started to go out he came down the last twenty cents in a single jump. That first dicker was our only hard one, and I think our starting to go out helped a great deal. We didn’t have to wrangle more than twenty minutes over the price on the smaller gas irons, and not at all over the price of the spring-pole, the spray can, or the starch. And Grace was positive it was the right kind of starch, because it was in little fine grains, like rice.

I think I might have saved as much as fifty cents on the small irons and other things, but Grace nodded her head before I was nearly through dickering, and you can’t do any dickering with a Chinaman after your sister has nodded her head. Until the things were all wrapped up and we’d paid our bill, I couldn’t figure out why Grace was in such a hurry to trade. Then she asked the storekeeper if he could tell us the quickest way to get to Scollay Square. The map he drew for us was easy to follow, and by six o’clock we were rapping on the door of Uncle Levi’s room.

Just after Grace knocked there was a tinkling sound, and when Uncle Levi came to the door he was sort of smacking his lips and brushing his mustache with the back of his hand. “Come in! Come in!” he half shouted when he saw who we were. “Gracie, girl, how be you? What in tunket did you fetch along, Ralph; a wagon tongue and anvil? How’s Mary Emma?”

Uncle Levi was the only one besides Mother who ever called Grace “Gracie.” She’d have skinned anybody else who tried it, but I think she liked to hear Uncle Levi say it. She didn’t act a bit prim when he hugged her up tight and kissed her, but giggled like a five-year-old, and at first she didn’t give me a chance to get a word in edgewise. As soon as Uncle Levi let her go she told him we were fine, and that Mother was fine, and that it wasn’t an anvil I was carrying but gas irons and a push-down pole. Then she began telling him about our going to Chinatown and dickering for the irons, and I think she’d have run on all evening if he hadn’t cut in and asked, “Et your victuals yet?”

“No, sir,” I said before Grace had any chance to head me off.

But I guess she didn’t think that was polite enough, and that she could fix it up so we wouldn’t sound too anxious. “Oh, we mustn’t stop . . . long,” she said, “Mother might worry about us. But, being right in the neighborhood, we thought we’d just stop in for a minute and say hello.”

“Thought you said you was down to Chinatown,” Uncle Levi said.

“We were,” Grace told him. “We just stopped by on our way . . . on our way to the subway.”

“Why, child alive,” he said, “there’s half a dozen subway stations twixt here and Chinatown. Didn’t you see. . . .”

When we’d come in I’d set the box of irons down right by the door, and as Uncle Levi was talking he bent over to move it. He’d just lifted it off the floor when he stopped in the middle of what he was saying and asked me, “You didn’t lug this cussed anvil all the way from Chinatown, did you?”

Grace started right in to tell him again that it wasn’t an anvil, but that time I interrupted her and said, “Yes, sir. It got kind of heavy along toward the last end.”

“It’s a God’s wonder you ain’t pulled your arms out,” he told me. “By hub, it must weigh nigh onto forty pounds. You children hold on till I go wash my hands, and we’ll hunt up some victuals. Want to come along with me, Ralph? Gracie, you’ll find the place where ladies wash their hands down t’other end of the hall.”

I’d bet almost anything that Grace found a big mirror in that ladies’ washroom. We had to wait nearly fifteen minutes for her, and when she came back she was all primped up, with little spitcurls peeping out from under her hat. Maybe it was just as well she took so long. It gave me a chance to tell Uncle Levi about our renting the big house on Spring Street, and our fixing it up, and Mother’s getting two customers, and about the shelves and table I was going to build for her.

When Grace finally did come back Uncle Levi sang out, “By hub, if you ain’t a spittin’ image of Mary Emma whenst she was commencin’ to grow up, my recollection’s playin’ tricks on me. Now, m’fine lady, where’d you like to eat your victuals?”

Grace patted her hair a couple of little dabs, and said, “Oh, we really mustn’t . . .”

I didn’t let her get any further, but said, “I saw a place in Scollay Square where a man in a white uniform was frying biscuits in the window.”

“Griddle cakes,” Uncle Levi said, “and tolerable good eatin’, too, along with a couple o’ pork chops and applesauce, and mashed potatoes and pan gravy, and butter beans and squash pie. Them Childs folks whacks up a larrupin’ good squash pie. How’d you like that, Gracie?”

If Grace ever had an idea that Mother would be worried about us she forgot it as soon as we sat down at the table in Childs. She didn’t usually talk very much, but that night she was wound up tighter than a dollar watch. She told Uncle Levi about Mother’s buying a whole houseful of real nice furniture for only fifty dollars, and about Mr. Perkins having the new soapstone tubs put in the laundry room, and everything else she could think of.

I ate so much that it’s a wonder I didn’t pop, but that was only because I didn’t have anything else to do. Grace didn’t let me get more than two or three words in until she’d told Uncle Levi about Mother’s insisting that all the laundry work be done in the basement, and about our cleaning up the laundry room, and what color she and Mother had painted it that morning, and that there was nothing left to be done except for me to build the shelves and table.

I think she’d have kept right on going if Uncle Levi hadn’t looked over at me and asked, “What kind o’ nails you goin’ to use?”

“Eight pennies, and sixteen-penny spikes,” I told him.

“Commons?” he asked.

I didn’t know just what he meant, so I said, “Well, just ordinary nails and spikes; I suppose they’re common.”

“Got ’em bought yet?” Uncle Levi asked me.

Before I could answer him Grace said, “Yes, sir. And the lumber and the ton of coal we’ve been waiting for, too. The men were just delivering them when I left the house.”

“You don’t say,” Uncle Levi said, sort of as if he were thinking about something else. Then he asked, “Frank’s folks been over since you got the place fixed up?”

“Uncle Frank has been over several times,” Grace told him, “but Aunt Hilda and the children haven’t. Mother says that when we get everything all finished we’re going to have a housewarming. Then they’ll all come over for a Sunday dinner with us, and we hope you’ll be able to come, too.”

“By hub, I will. I will,” Uncle Levi said quickly. “Always did like a housewarmin’. Like to see all the little shavers roundabout a big table, pokin’ away the victuals till they’re fit to bust. Always did calc’late that folks ought to move about onct a year, so’s to have plenty of housewarmin’s.”

As Uncle Levi spoke he took his big watch out of his vest pocket, glanced down at it, and said, “By hub, here it is nigh onto eight o’clock. If Mary Emma’s goin’ to worry about you children she’s likely hard at it a’ready. Leave me lug that anvil, Ralph; I’ll see you over to the subway and get you headed in the right direction. For folks that ain’t used to it, Boston can be devilish hard to find your way about after nightfall.”

Uncle Levi took us as far as the entrance to the subway station, and after we’d thanked him for our supper he told us, “Don’t never thank me for victuals! If there is anything in this world I like to see better’n a parcel of little shavers sittin’ up to table and stuffin’ their bellies, I don’t know what it is. You tell Mary Emma I ain’t goin’ to wait much longer for that housewarmin’ of hers.”

I was so full of supper that I couldn’t help going to sleep on the subway train, so I don’t remember much about that trip home, except that our feet nearly froze on the way from the carline to our house, and that the box of irons grew heavier with every step.

Mr. Haushalter told me that Philip did a real good job at the store, and at nine o’clock that Saturday night Mr. Durant called me over to his desk and gave me a two-dollar bill. “I didn’t pay your brother,” he told me. “You can settle that between you. The extra fifty cents is for those rough evenings we had during the storm.” Before I left for home I changed the bill, so I’d have a fifty-cent-piece for Philip.

Hal and Elizabeth had gone to bed before I got home, but the rest of the family was in the parlor, and Mother was reading aloud. I came in through the kitchen door, put my dollar and a half in Mother’s purse, and took the fifty-cent-piece in to Philip. He grinned from ear to ear when I gave it to him, and then took it over to Mother. “Isn’t that nice?” she said as she looked up from the book. “Why don’t you put it in that little bank that came with our furniture and save it?”

“Doesn’t Ralph put his money in your purse?” he asked her.

“Why yes,” Mother told him, “but, you know, Ralph is the man of our family, and . . .”

Mother must have noticed as quickly as I did that Philip’s lip was beginning to tremble, because she hesitated for only a moment before she went on, “. . . and you are my man, too, so you run right out and put your half-dollar in with Ralph’s.”

I think Philip was as proud of earning that fifty cents as if it had been fifty dollars, and he was all smiles again when he came back to the parlor. Mother read to us that night until after eleven o’clock.