‘What are you going to tell your parents?’ asked Oddo. ‘They won’t want you to sail to Ireland in that silly curach.’

Thora shrugged. ‘It wouldn’t worry them. They know I can look after myself. But I don’t think I’ll tell them, anyway. I’ll just say I’m going to Gyda’s to fetch the silver.’ Oddo was silent. ‘It’s not a lie. I will go to Gyda’s – on the way back.’

‘Not if the boat sinks, and you’re drowned.’

‘It won’t sink. Dúngal’s going to cover the leather with fat to make it waterproof.’

‘And where does he think he’s going to get all the fat from?’

‘I’ll get it. I’ll go round and ask all the farmers to save me their fat next time they kill a sheep. I’ll pretend I need it for my potions.’

Oddo shook his head. ‘You’re mad, risking your life for that poophead.’

But the next time Bolverk slaughtered a sheep, Oddo filled a bucket with blood-streaked lumps of yellowy fat and carried it through the wood to the house-over-the-hill. He found Thora in a cleared patch among the weeds, tending her herb garden.

‘Look how everything’s growing,’ she called excitedly. She showed him the little pea plants with their tiny curling shoots, the buds of baby cabbages, the scented rosemarin. ‘I could do with a bit of rain, though.’

Then she noticed the bucket in his hand. ‘Oh! Is that for the boat? I can boil it right now.’

‘Can’t let you both drown,’ growled Oddo.

The sound of raindrops followed them into the house.

Inside, the room was thick with smoke. Oddo picked his way across a floor covered with mysterious lumps. He trod on something by mistake, and it squelched unpleasantly under his foot. Screeching figures leapt out of the gloom. Oddo dodged as Granny Hulda, followed by Astrid and Edith, danced round him, tossing objects in the air and singing a strange chant. Something landed on Oddo’s head and bounced onto the floor. It was a dead bird. Thora swooped on it eagerly.

‘That’ll do for supper,’ she said happily.

Oddo felt a sticky cobweb trail across his face; and the herbs hanging from the rafters sprinkled dusty, scented leaves on his hair.

They reached the firepit where little Ketil was rolling a lump of dough on the floor.

‘Cook it now!’ he said, holding it up. It was grey and covered with lumps of grit and feathers.

Thora’s mother, Finnhilda, took it from him. But instead of setting it to cook on a griddle, she thrust her bare hand into the flames, and held it there, muttering a spell.

Granny Hulda stopped prancing, and hovered, her beady eyes roving around the room, her thin fingers plucking the air. She looked like a small, curled-up beetle.

‘Is that the farmer’s boy,’ she asked, ‘the one who thinks he can do spellwork?’

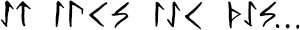

A lanky boy shot up in front of Oddo. ‘What runes do you know?’ Erik demanded.

‘I . . . can’t do runes,’ said Oddo.

‘Huh.’ Erik tossed a stone that almost hit Oddo in the face.

‘Can you turn invisible? I can turn invisible.’ Ketil leapt up from the floor and ran to fetch his goatskin cloak.

‘What about flower spells? Can you do this?’ asked Edith. ‘Show him, Sissa.’ A tiny girl with wide eyes and wispy hair picked up a log from the woodpile. A moment later, leaves and flowers sprouted all over it. The child chuckled, and Oddo shook his head.

‘He can’t do anything,’ sneered Astrid. ‘It’s just Thora’s boasting.’

‘He can too!’ Oddo was startled by the fury in Thora’s voice. ‘Show them, Oddo.’

Embarrassed, Oddo glanced at the chimney hole. Everyone was watching. He was about to call for a spot of rain, when a siskin darted across the space with a flutter of yellow feathers.

‘Hey,’ he called. ‘Come here.’

The little bird turned in mid-flight, dived through the hole and alighted on his outstretched hand.

‘That’s not hard,’ said Astrid.

Oddo bent his mouth close to the feathered head, and whispered.

The next moment, the siskin swooped across the room, and grasped a strand of Astrid’s hair in its tiny beak.

‘Ow!’ squealed Astrid, and tried to pull free. But the bird kept tugging as if it was pulling on a juicy worm. ‘Ow! Make it let go!’

‘What a pity,’ said Oddo. ‘I’m not very good at spellwork. I don’t know how to make it stop.’

He winked at Thora. Hastily she bent her head and tipped the lumps of fat into a cauldron.

While Astrid ran around the room squealing and holding her head, Thora added water and hung the pot on the fire. Her other brothers and sisters chased after Astrid, shouting instructions. Oddo caught the siskin’s eye. It let go and flew away.

Astrid came to a halt, panting, her face scarlet. ‘You . . . You . . .’

‘You asked for it, Astrid,’ chortled Harald, and skipped out of the way as she spun towards him.

The fat in the cauldron began to bubble. Shrivelled grey cracklings and bits of blood and foam rose to the surface. ‘Like boats in a sea,’ said Harald, peering over the edge.

Oddo stared at the crispy curls swirling among the bubbles.

‘Bet they float better than Dúngal’s curach,’ he muttered. He glanced at Thora.

She ignored him, and used a wooden ladle to skim the surface. Harald snatched a piece of crackling and popped it in his mouth. Oddo stared as his teeth crunched it into flakes, and imagined a tiny boat, disintegrating . . .

‘Thora, you’re not really planning to go off in that joke of a boat, are you?’ he demanded.

Thora pursed her lips, sat down and began to pluck the feathers off the dead bird.

‘Stir the pot for me, will you?’ she said.

A whirlwind of floating feathers was added to the fumes of smoke and boiling fat.

Oddo stared at his friend, and imagined her trying to sail all the way to Ireland in the curach. With only that blockhead for company.

At last, Thora covered the opening of an empty keg with a piece of weaving, and asked Oddo to hold it while she tilted the cauldron. He turned his face away as the liquid fat poured out in a stinking, steaming stream – through the cloth and into the keg.

‘Now, I’ll leave that in the storehouse to cool,’ said Thora. ‘Tomorrow there’ll be a clean layer of white fat sitting on the top, and that’s what Dúngal will use on his leather.’

On the way home, clothes and hair reeking of fat, Oddo passed the bramble patch where Dúngal was building his boat. He halted, and looked around. There was nobody in sight, and no sound coming from the brambles. Furtively, he slid into the tunnel.

On the other side, he scrambled to his feet and gazed at the curach. It was even smaller than he’d remembered. Compared to a wooden Viking ship, it looked as fragile as the skeleton of a bird. Could it really cross the sea to another land?