Dúngal opened his eyes. He was lying face down on a beach. A wave poured over his head, then melted away, and the white bubbles of spume sank into the wet black sand around him.

His belly gave a heave and seawater poured out of his throat.

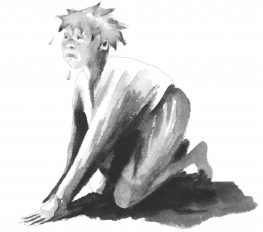

Another breaker rolled towards him. Retching and gulping, he struggled to his hands and knees and began to crawl up the beach. The broken end of the rope around his waist trailed behind. To his right reared the huge shadow of a cliff.

‘Thora?’ he called.

His cry was blown away by the wind and rain. He turned to look for the curach, but all he could see was empty sand. He stumbled to his feet and began to run, tripping and scrambling, across the beach. He reached the cliffs and searched frantically among the shadowy hollows and the stony shards. But there was no movement; no answer to his cries. Only the eerie scream of gulls.

Wrapping his arms around his wet, shivering body, he huddled against the rocks, feeling as lonely and helpless as a hatchling fallen from its nest. Rain pelted his face. He tilted back his head and opened his mouth, but only a few tantalising drops landed on his parched tongue. In desperation, he turned and licked the wet, glistening surface of the cliff.

It tasted of salt.

He slumped back and gazed across the cove.

‘I’m the only one left,’ he thought.

There was no sign of any people. No boats, no fishing nets. Nothing. Only a black void of sand and pebbles, and then more jagged rocks, more cliffs. In front of him, the pounding waves rolled empty and relentless towards the shore. He picked up a fistful of shiny pebbles, and hurled them across the beach.

There was a beating of wings as a cluster of kittiwakes, paddling in the spume, rose, startled, into the air. They coasted on the wind, circling and screeching. But on the rocks below, one pale wing still lifted and dipped, lifted and dipped. Dúngal watched it, puzzled. Then suddenly hope spurted through him. Maybe it wasn’t a bird. Maybe . . .

He leapt to his feet and began to run. And now he could see, draped across the rocks, a grimy, tattered cloth. His sail! Once again, a corner lifted in the wind, and beneath it he caught a glimpse of small, white toes.

‘Thora!’

He lurched forward, grabbed the edge of the sail, and yanked. Oddo was sprawled there, and beyond him, her fingers still twined around his belt, was Thora. She was lying against the boulders, her wet hair trailing like seaweed, her eyes closed.

‘Uch, Thora!’ Dúngal gripped her shoulder and shook. Thora’s head rolled and she let out a groan. Then her eyes flickered open. She stared at him.

‘Where’s Oddo?’ she whispered.

Dúngal pointed beside her. ‘There. You’re holding onto him!’

She turned to look, then let go of the belt, and rubbed her fingers. Shakily, she sat up.

At that moment, a wave slid up the beach. It curled around their legs and washed over Oddo’s face. ‘Help!’ Thora lifted Oddo’s head. ‘We’ve got to move him.’

Oddo’s limp body felt as heavy as a whale’s. Slowly, painfully, they eased him a short way up the beach, and paused, panting for breath. ‘All right, one more heave.’

Dúngal gritted his teeth, dug in his fingers and yanked. Oddo slid across the stones and ground to a halt. Dúngal and Thora collapsed beside him.

‘I’ll never move again,’ groaned Dúngal.

From the corner of his eye, he saw Thora struggle to sit up. He saw her stretch an arm to something green on the cliff above her head.

‘Dúngal?’ she croaked. ‘Can you reach? It’s sea fennel. Good to eat.’

He looked. He imagined the sweet juice running down his throat. Somehow he rose to his knees, and a moment later the two of them were greedily sucking the liquid from the long, fleshy leaves.

‘Better,’ said Thora. ‘Only . . .’ She frowned round, and then began to crawl across the sand. Dúngal gazed after her, but he had about as much energy as a strand of seaweed. He sank down and closed his eyes.

He was woken by the sound of crunching. A strong, sweet perfume drowned out the smells of sea and salt. Dúngal eased one eye open.

‘Want some?’ Thora was chewing on a thick, purple stem, while yellow juice dripped down her chin. ‘Angelica. It will make you feel better.’

Dúngal struggled to sit up and held out his hand. Thora was right. As he chewed, his body tingled back to life. In a few minutes he even felt strong enough to stand. He took a few tentative steps and grinned in delight. His legs felt almost normal. He glanced out to sea. A little head with perky black ears was bobbing on the surf.

‘Hey, look!’

The wave swept up the beach, and a wet, spiky bundle dropped onto the sand. It staggered to its feet, gave a feeble shake and tottered towards them.

‘Hairydog!’ Thora threw her arms around the shivering creature and offered her some leaves. ‘We’re all together again!’ she hooted. ‘And we’re all safe.’

‘But . . . We’re stuck here,’ stammered Dúngal, ‘with no boat. And Oddo . . . He’s still . . .’ He looked at the blank, staring face.

‘Then we’ll get a boat. And a fire.’

‘How?’ Dúngal looked around the empty cove. ‘Where?’

‘There must be some people in this place,’ said Thora. She pointed across the sand, and for the first time Dúngal noticed a patch of grass beyond the cove. ‘I reckon that’s a farm.’ She scrambled to her feet. ‘Let’s go and look. Hairydog, you stay with Oddo.’

‘Wait!’ Dúngal snatched up a length of driftwood and hefted it in his hand. ‘You take one too.’

‘What for?’

‘How do we know the people will be friendly?’

‘But . . . Oh, all right.’

They hurried past the walls of the cliffs, their feet scrunching on the sand and pebbles. Then they stepped out onto springy grass.