‘It’s a woman,’ breathed Oddo.

Dúngal, too, saw the long robe flowing to the ground. It was the colour of the rocks, and girded at the waist with a cord. But then he noticed the hair – long on the neck, but shaven from ear to ear.

‘That’s no woman!’ he cried, his voice ringing in excitement. ‘That’s a priest!’ He ran forward, shouting in his own tongue. ‘A Athir! A Athir!’

The priest turned in astonishment and put out his hands to catch Dúngal as he hurtled forward.

‘Fáilte!’ he cried, and at the sound of the Irish greeting, Dúngal thought he would burst. ‘Uch, boy, what are you doing so far from home? How came you here?’

Dúngal stared with delight at the shaven chin, so different from the Vikings’ long, rough beards. He looked into eyes that were the pale, transparent blue of the sky.

‘I was captured by Viking raiders. I built a curach and tried to get home, but . . .’ Dúngal’s chin quivered and he felt tears welling up. He gulped. ‘But I ended up here!’

‘And who are you, child? What is your name?’

‘I’m Dúngal macc Flainn of Laigin.’

‘And I hail from the monastery of Cill Dara. My name is Connlae.’

Father Connlae’s voice was soft and rustling, like the wind through leaves. He was a small man, elderly and shaky. His hand trembled as it rested on Dúngal’s sleeve. But his face was curiously unlined, just like the abbot’s at the monastery where Dúngal had learnt his letters.

Dúngal heard Thora and Oddo coming up behind him, and Hairydog’s panting breath. The dog’s muzzle butted his knee and he stroked her head. ‘This is Hairydog, and these are my friends, Oddo and Thora. They’re Vikings, but they helped me. And now, because of me, they’re stranded too.’ He looked around at the bulky shape of the mountain and the shadowy trees. ‘What is this strange land, anyway?’ he asked. ‘Are there other people here from Ériu?’

Father Connlae shook his head.

‘No longer. I am the only one from Ériu now. There were other Brothers with me, but they have left. For the Vikings are arriving now. Even here, in this place of peace and prayer, they find us and harass us.’

‘Vikings? Where? We didn’t see them!’

‘No, as yet there are but few. They have settled yonder.’ He lifted a trembling hand. ‘In the west.’

Dúngal felt Oddo pinching his arm.

‘What is it? What are you saying? What’s he telling you?’

‘He says there are Vikings here.’

‘Here? But what is this place?’

Dúngal turned back to the priest and caught a puzzled expression on his face. ‘You can speak to these people in their language?’ he asked.

Dúngal nodded proudly. ‘And they’re asking you the name of this place,’ he said.

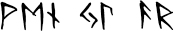

‘The Vikings call it Iceland.’

‘Iceland? But what about the fire? I’d call it Fireland!’

‘Yes,’ said the priest. ‘Buried beneath the mountains of ice, there is a heart of fire. But it is a land of bounty, too. My goats and I never want for food. The rivers teem with fish, there is endless pastureland . . . It was a haven till the dreaded Vikings came. And now, I live in fear that they will find me and make me their slave.’

‘Why don’t you go back to Ériu, then?’

‘Uch, how I long to leave. But I have no boat. I chose to remain when the other Brothers left, and now . . .’ Sadly he shook his head. ‘But enough about me, you are weary and hungry. Come, bring your friends and share my supper.’

He ushered them towards a crevice in the side of the mountain, and they squeezed through to find themselves in a cave. There was dry grass on the floor, and furniture made from branches and rough-hewn logs.

‘This must be his house,’ whispered Thora, her voice faltering as she eyed the laden table in the middle of the room.

‘Father Connlae says have biad – food!’ said Dúngal.

They all dived at the table. There was a round, flat bread made from wild grass seeds, strips of dried fish topped with a sweet relish of sea fennel, and a bowl of white, lumpy curds.

Dúngal snatched up the bread and crammed most of it into his mouth at one bite.

‘Hey,’ said Oddo, ‘how about the rest of us?’

Dúngal felt his face burning. He pulled the loaf out of his mouth. It was damp and slightly mauled.

‘Sorry. Want some?’

‘Not now!’

‘Please don’t argue. There is plenty of food.’ Father Connlae heaved open a wooden chest. He drew out handfuls of shrivelled fruit, nuts and seaweed and poured them on the table. ‘Here, here.’ With shaky hands he thrust them towards the children. ‘Eat.’ He beamed and nodded, picking up titbits and pushing them into their hands whenever they paused.

‘Tell him I can’t eat any more!’ said Thora.

‘Me neither!’

The three friends collapsed on a heap of soft heather at the side of the cave.

‘What’s this?’ Thora picked up a book lying on the floor and lifted the cover. ‘It’s names, like you drew in the dirt, Dúngal. Lots of names!’

Dúngal took the book and read a few lines.

‘It’s not just names. It’s a story.’

‘A story?’ Thora brushed her hand over the soft, white page. ‘And what’s this stuff it’s drawn on?’

‘Skin from a . . . lóeg . . . a calf.’

Thora and Oddo looked inquisitively around the room.

‘And what are those funny torches made from?’ Oddo pointed at candles stuck on rocky projections around the walls.

‘I . . . don’t know how to say it in your tongue. It comes from the bees.’

‘Is that what you have in Ireland? Why don’t you just use wood, or fish oil, like we do?’

‘It lasts longer, I think.’

‘It smells nicer too.’

The priest was watching them talk, beaming, his head moving from side to side as each one spoke. Then the candle over Thora’s head gave a sputter and began to smoke. Father Connlae rose to his feet.

‘It is time to sleep.’ He snuffed out the sputtering candle. ‘Please, lay your heads here.’ He patted the heather they were sitting on. ‘And cover yourselves with these.’ He handed them a bundle of goatskins, then moved around the room, snuffing the other candles.

‘He says to go to sleep.’ Dúngal yawned, and leaned back.

‘Tomorrow,’ said Thora, ‘we’ll find those other Vikings. And their longships!’

‘No!’ Dúngal shot up again. ‘You can’t do that! If they see me, they’ll make me into a thrall again. And Father Connlae too!’

By the faint glow of a single candle, Oddo and Thora gaped at him.

‘Then how are we supposed to get out of this place?’

There was no answer. The last light went out. In miserable silence, the three weary travellers lay down. They were shivering now in their cold, wet clothes. Groping in the darkness, Dúngal tugged a goatskin over himself and curled up, trying to get warm.