1

Ellen Louise Axson, a Presbyterian minister’s daughter, met Woodrow Wilson, a Presbyterian minister’s son, in 1883. They married two years later.

1

Ellen Louise Axson, a Presbyterian minister’s daughter, met Woodrow Wilson, a Presbyterian minister’s son, in 1883. They married two years later.

4

Mary Allen Hulbert Peck met Wilson in Bermuda, where he sometimes took a respite from his duties at Princeton. Estranged from her husband, she was vivacious, intelligent, and sympathetic. When she and Woodrow became friends, Ellen suspected an affair. Both Woodrow and Mary denied it. The available evidence supports their denial, but his political enemies floated the gossip in hopes of derailing his 1912 and 1916 presidential campaigns.

5

Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey and his family, at Sea Girt, New Jersey, in the summer of 1912, when he received the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. (Behind Woodrow and Ellen, left to right: Jessie, Nell, and Margaret.)

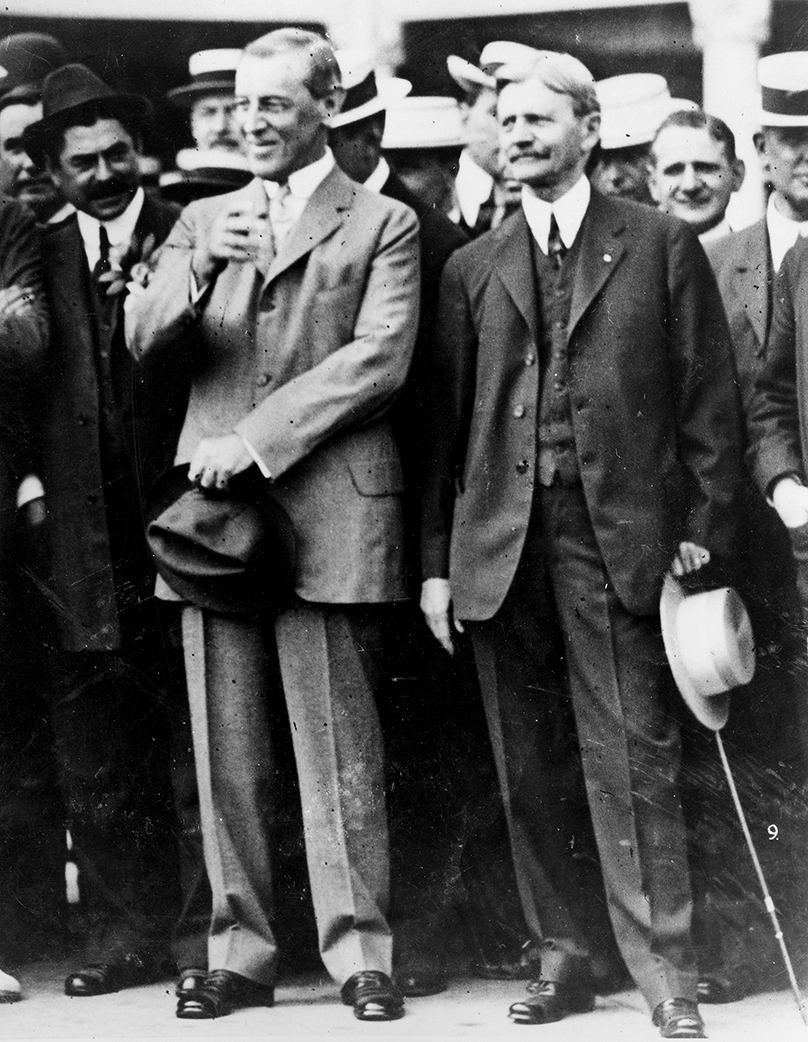

6

Wilson’s running mate, Governor Thomas Riley Marshall of Indiana, was chosen by party leaders with their eyes on Indiana’s fifteen electoral votes.

7

Ellen and Woodrow Wilson leaving Princeton for Washington on March 3, 1913, the day before his inauguration.

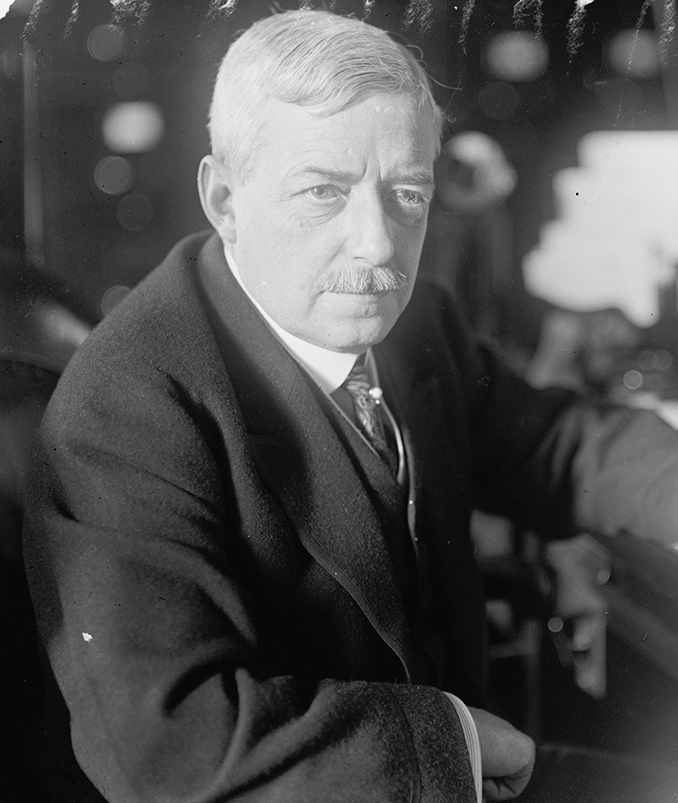

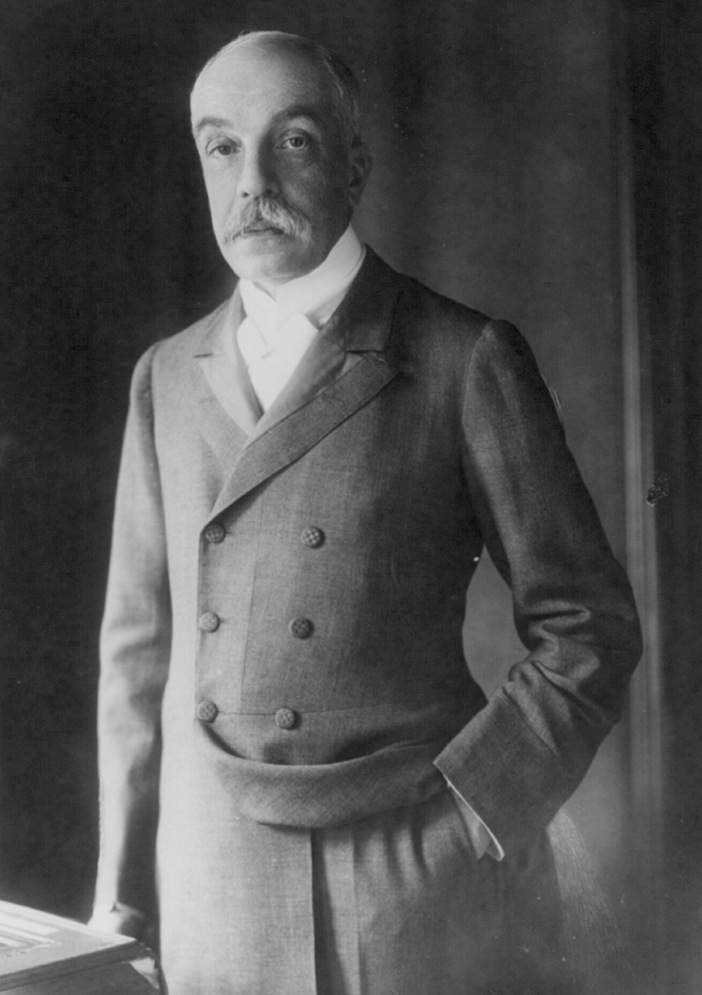

11

Wilson’s most trusted advisors: his wife, Ellen (First Image); his secretary and chief aide, Joseph P. Tumulty; his minister without portfolio, Edward M. House (Third Image); and his physician, Captain Cary T. Grayson (Fourth Image).

15

Wilson had cool relationships with the four cabinet members he needed most. Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson (First Image) and Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo shepherded the president’s legislation through Congress. Determined to act as his own secretary of state, Wilson was relieved when William Jennings Bryan (Third Image) resigned in 1915. Five years later, Wilson fired Bryan’s successor, Robert Lansing (Fourth Image), accusing him of disloyalty.

19

The United States was a neutral in the world war until 1917, but soon after the war began, in 1914, the U.S. government and the Great Powers found themselves at odds on a host of issues. Wilson involved himself in critical situations, but most problems were addressed by the secretary of state in consultation with the key ambassadors: Cecil Spring Rice of Great Britain (First Image), Jean Jules Jusserand of France (Second Image), Johann-Heinrich von Bernstorff of Germany (Third Image), and Konstantin Dumba of Austria-Hungary (Fourth Image).

20

In March 1915, seven months after the death of Ellen Wilson, Woodrow was introduced to Edith Bolling Galt, a Washington widow sixteen years his junior. Adventurous and glamorous, she was the first woman in the capital to own an electric car. He proposed in May, their engagement was announced in October (a few days before they were photographed at a World Series game), and they married in December.

23

When Wilson’s reelection campaign adopted the slogan “He kept us out of war” in 1916, many voters thought it meant that he would keep country out of the world war—a promise he never made. Above all, he feared that a German U-boat attack with substantial American casualties would sweep the United States into war. It almost happened a month before the 1916 election, when the U-53 (above) sank nine merchant ships off the New England coast. But none of the ships was American, the raid took place just outside U.S. waters, the U-53’s commander allowed the crews to evacuate, and all hands were rescued.

24

“He kept us out of war” referred to war with Mexico, where a long revolution had caused widespread losses of American lives and property. In March 1916, after the rebel leader Pancho Villa stormed into New Mexico and killed more than fifty Americans, Wilson authorized a five-thousand-man “punitive expedition” into Mexico under the command of General John J. Pershing. The mission: capture Villa and defeat his army. Villa remained at large.

27

Like Wilson, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (Second Image) and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels (First Image) were pacifists.

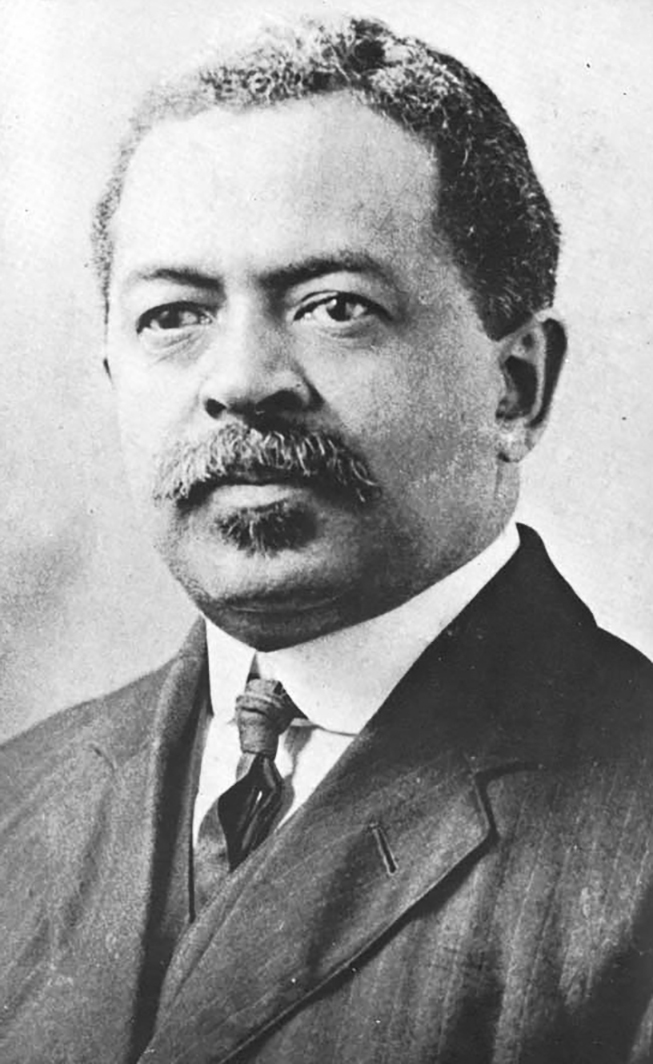

30

Wilson was a frequent target of protest by women who wanted the right to vote, African Americans in search of equal rights, and citizens who opposed U.S. involvement in the world war. Eugene V. Debs, leader of the Socialist Party of America (Second Image), went to prison for obstructing the draft. William Monroe Trotter (Third Image) of the National Equal Rights League pressed Wilson to end his administration’s segregation of the civil service.

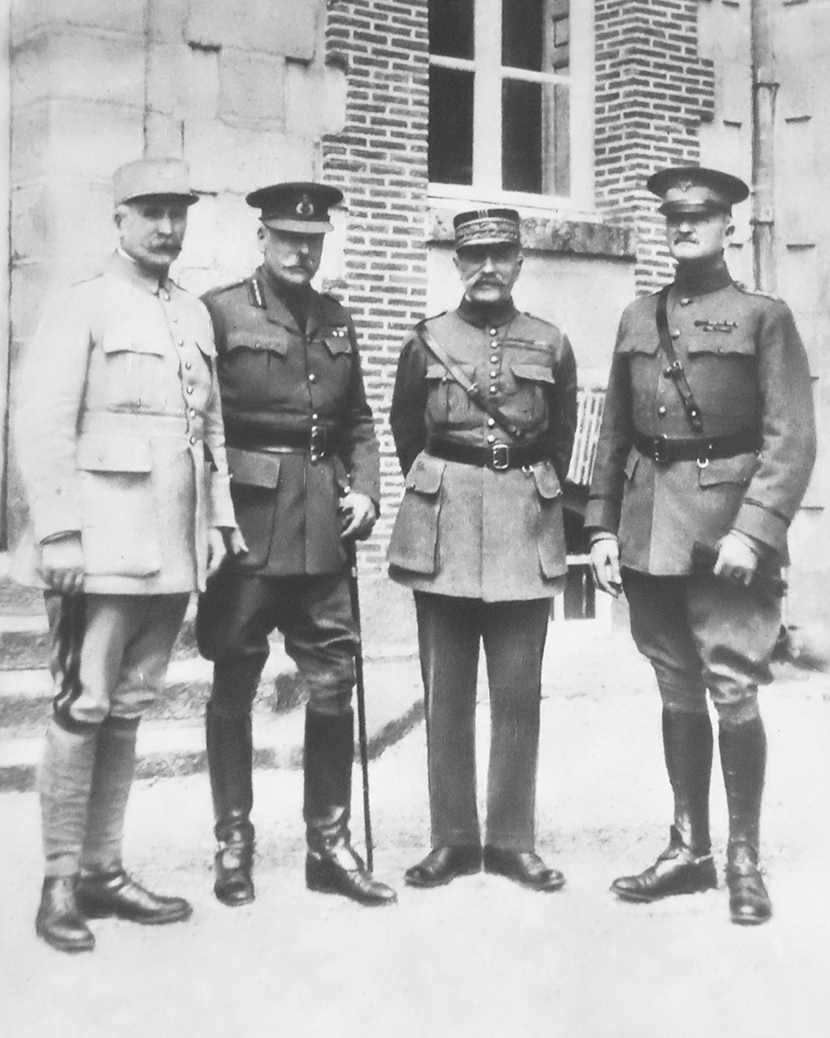

31

As the U.S. commander on the Western Front, General Pershing fought one war on the battlefield and another with French and British commanders who wanted to put American troops into their lines. Pershing cooperated with the Allied armies but fielded an independent force—with Wilson’s blessing—to ensure that U.S. military contributions were plain to all.

35

(First Image) Baron Nobuaki Makino, Japan’s chief negotiator at the peace conference. Wilson blocked the Japanese delegation’s efforts to include a clause on racial equality in the covenant of the League of Nations. (Second Image) V. K. Wellington Koo, the thirty-one-year-old leader of the Chinese delegation to the peace conference. During the war, Japan captured Germany’s leasehold in the Chinese province of Shantung. Afterward, China wanted the peacemakers to restore its sovereignty over the region. At Wilson’s urging, the Japanese promised an exit in the future but balked at putting their pledge in the Treaty of Versailles. Bitterly disappointed, the Chinese refused to sign the treaty.

38

On October 2, 1919, Wilson had a stroke that permanently paralyzed his left side and rendered him nearly blind. Dr. Grayson and Edith Wilson orchestrated an elaborate cover-up of the seriousness of his physical condition. Eight months later the Wilsons posed for this photograph in hopes of convincing a skeptical Congress and the public that the president was in good health, of sound mind, and on the job. Wilson was still seriously impaired. His adamant refusal to consider Republican modifications to the Treaty of Versailles contributed significantly to its defeat in the Senate. As a result, the United States never entered the League of Nations, which Wilson had given his all to establish.

40

Believing himself much healthier than he was, Wilson made a covert bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1920. He sent his new secretary of state, Bainbridge Colby (First Image), to the party’s national convention with instructions to wait for a deadlock and then put Wilson’s hat in the ring. Party leaders who got wind of the scheme convinced Colby that nominating Wilson for a third term would ensure the Democrats’ defeat. The eventual nominees for president and vice president, Governor James M. Cox of Ohio (Second Image) and Franklin D. Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the navy, visited Wilson at the White House a few days later.

42

Woodrow and Edith Wilson took part in the funeral procession for the American Unknown Soldier, whose coffin was carried through the streets of Washington to Arlington National Cemetery on November 11, 1921. Unable to negotiate the stairs at Arlington’s amphitheater, Wilson left the procession near the White House. A crowd of five hundred admirers fell in behind his carriage and followed him to the house where he lived after his presidency, at 2340 S Street.