The primary figure behind all US naval strategy during World War II and the driving force for the offensive into the Solomons in August 1942 was Admiral Ernest J. King. After both surface ship and submarine billets, he transferred to naval aviation in 1926. He earned his wings in 1927, and assumed command of the carrier Lexington in 1930. In 1933, he was promoted to flag rank and assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics. In 1938, he was promoted to vice admiral and was appointed Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force. His career looked to be over in June 1939 when, instead of being promoted to Chief of Naval Operations, he was posted to the General Board. With America’s entry into the war looking more and more certain, King’s career was resurrected in January 1941 when he was appointed as the Commander of the Atlantic Fleet. No other admiral in the Navy possessed the undisputed toughness and leadership skills of King. Following Pearl Harbor, King gained more authority as the Commander-in-Chief US Fleet (COMINCH). In March, he was also appointed as Chief of Naval Operations, giving him ultimate authority over all US naval strategy and operations.

Admiral Ernest King, pictured here in 1942, was the guiding force behind US naval strategy worldwide. It was his vision to launch an immediate counterattack in the Solomons in the aftermath of the victory at Midway. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

With his sweeping authority, King expanded the Navy’s freedom of action in the Pacific, which, under the “Germany First” strategy, was clearly defined as a secondary theater. It was King that directed South Pacific strategy in 1941 and into 1942, not the Commander of the Pacific Fleet. He did not think that the Germany First strategy meant only defending key areas in the South Pacific and securing the sea lines of communications to Australia. Rather than conduct a passive defense, King was determined to begin offensive operations as soon as possible in the Pacific. The first step on the road to Rabaul was the invasion of Guadalcanal in August 1942.

The commander of the US Pacific Fleet, effective December 31, 1941, was Admiral Chester Nimitz. His early background was mainly in submarines, and later he served on cruisers and battleships. He had no background in naval aviation. Following the disaster at Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was the personal choice of President Roosevelt who had been impressed by Nimitz during his two tours in Washington. The qualities possessed by Nimitz would be in great demand as he tried to rebuild the fortunes of American naval power after Pearl Harbor. Besides being recognized as a capable administrator, his calm and determined demeanor made him the right person for the job. He also had an uncanny ability to pick good leaders and then give them the authority to accomplish their mission. Another trait which became increasingly apparent was his aggressiveness and strategic insight. These were displayed at the victories of Coral Sea and Midway. On April 3, Nimitz was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Ocean Areas in addition to his duties as Commander of the Pacific Fleet. This made Nimitz responsible for the execution of King’s plans to launch offensive operations as soon as possible in the South Pacific. However, Nimitz did not exercise direct control of operations in the South Pacific since this was the responsibility of the Commander, South Pacific Area.

Admiral Chester Nimitz, pictured here in 1942, was not in direct command of the Guadalcanal battle, but he was responsible for keeping the battle adequately resourced with assets from the Pacific Fleet. The relief of Ghormley by Halsey in October was a critical move. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, photographed here in 1942, possessed the capacity to lose the Guadalcanal campaign, with his lack of command experience and a pervasive pessimism about the prospect of success. Nimitz identified his harmful effect on American morale and relieved him just before the major Japanese offensive in October. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The finest moment of Vice Admiral William Halsey’s career was when he assumed command of the South Pacific area when American fortunes on Guadalcanal were at a low ebb. His fighting spirit provided an immediate boost to morale. However, his aggressiveness at Santa Cruz translated into recklessness. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley assumed the post as Commander, South Pacific Area on June 19. He held this position up until October 18, so he was in overall command during Eastern Solomons but was not present at the time of Santa Cruz. Ghormley was a controversial figure. While he has been described as possessing undoubted intelligence and a gift for diplomacy, he possessed no real command experience and was unable to provide confident leadership. The American campaign in the Solomons was a poorly resourced affair, and Ghormley was unable to work within that reality.

Vice Admiral William F. Halsey relieved Ghormley as Commander, South Pacific Area just before Santa Cruz. Halsey was the senior ranking US Navy carrier commander and, without a doubt, was the most aggressive. When Nimitz looked for an admiral to boost the morale of the men fighting in the Solomons, the natural choice was the flamboyant and ultra-aggressive Halsey.

The most combat-experienced American carrier commander going into the Guadalcanal campaign was Vice Admiral Frank “Jack” Fletcher. He was in command of the American carrier force at the battle of the Coral Sea and was commended by Nimitz for his performance. This success, and the fact that Halsey fell ill, prompted Nimitz to place him in overall charge of the American carrier force operating off Midway. It’s important to remember the major role Fletcher played in executing the initial strikes which caught the Japanese carriers flat-footed. He was described by his peers as unpretentious and possessing strength of character, but tended toward caution unless he thought risks were warranted. By the time of the Guadalcanal campaign, especially after his early withdrawal of the carriers immediately following the landing, the criticism of his being overly timid grew louder. Fletcher had the backing of Nimitz, but not of King. After the Eastern Solomons, Fletcher was due for a rest period back in the US, and King made sure he never received another carrier command.

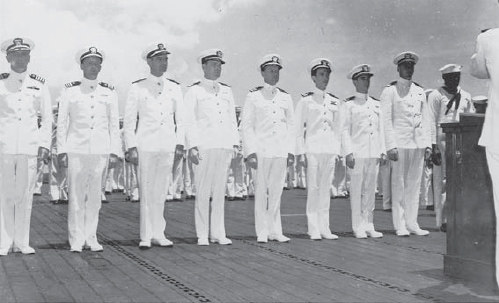

George Murray, shown here on the left as a captain during an awards ceremony on Enterprise in May 1942, was commander of TF-17 at Santa Cruz. He was one of the pioneers of American naval aviation. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher photographed on September 17, 1942. Shortly thereafter, he was sent home for leave and never returned to a carrier command. He is the forgotten hero of Coral Sea and Midway. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid exercised overall command of the American carrier force at the battle of Santa Cruz. He was a veteran of Coral Sea and Midway. When Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance was moved from commander of Task Force (TF) 16 following Midway to be Nimitz’s chief of staff, and with Halsey still laid up since May 26 with a skin disease, command of TF-16 was given to Kinkaid. His peers described him as a clear-headed professional. Kinkaid was the last non-aviator to command an American carrier task force in battle. After Santa Cruz, he was relieved by an aviator. Kinkaid went on to have a fine war record as the commander of the amphibious forces tasked to recapture Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians and then as commander of the 7th Fleet.

The commander of TF-17 was Rear Admiral George D. Murray. He was a pioneer naval aviator and formerly the commanding officer of the carrier Enterprise and was close to Halsey, his old task force commander.

By law, commanding officers of US Navy carriers were required to be aviators. The captain of the carrier Saratoga was Captain Dewitt W. Ramsey. Hornet was commanded by Captain Charles P. Mason. Enterprise’s skipper was Arthur C. Davis at Eastern Solomons and then Captain Osborne Hardison at Santa Cruz.

The Commander of the Combined Fleet was Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku. He had assumed this position after being a Navy Vice Minister when he fought a prolonged action to delay the IJA’s drive to assume total control of Japan’s foreign and security policies. His assumption of the command of the Combined Fleet was an effort to get out of Tokyo and out of the line of fire of radicals who had threatened to assassinate him. Despite being a forceful advocate of avoiding war with the United States, he now found himself in the position of having to discharge his professional duties by preparing for the war he sought to avoid. He promptly proceeded to make the biggest mistake of his professional life by personally and powerfully advocating that the war against the Americans should begin with a blow against the heart of American naval power in the Pacific at Pearl Harbor in order to crush American morale. Of course, the attack had just the opposite effect. Though marginally successful in a military sense, its political ramifications forever undermined any prospect of a negotiated peace with the United States. Nevertheless, Pearl Harbor and the ensuing period of Japanese expansion, cemented Yamamoto’s reputation for brilliance while confirming his predilection for gambling. Yamamoto’s performance after Pearl Harbor was less than stellar. His overconfidence led to the fatal compromise with the Naval General Staff which in turn led directly to the failed offensive into the Coral Sea in May 1942 and the disaster at Midway in June.

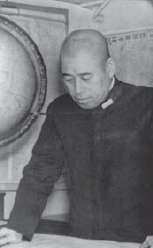

Yamamoto’s conduct of the Guadalcanal campaign was weak and indecisive. His failure to recognize Guadalcanal as the decisive battle he had been seeking condemned the IJN to a battle of attrition it could ill afford. Ironically, Yamamoto was killed a few months after the end of the struggle for Guadalcanal by American fighters based on the island. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Vice Admiral Nagumo Chuichi was the most experienced carrier commander in the world by the start of the Guadalcanal campaign. Unfortunately for the IJN, not all of his experiences were good. After the defeat at Midway, he showed great caution during the two carrier battles at Guadalcanal. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake was an important, if overlooked, figure in the naval battles for Guadalcanal. He held important commands during Eastern Solomons, Santa Cruz and at the climactic naval battles in November. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The defeat at Midway ended Japanese expansion and seemed to throw Yamamoto off balance. When the Americans grabbed the initiative in August by landing on Guadalcanal, Yamamoto was slow to respond. Though the Combined Fleet still possessed a significant margin of strength over the Pacific Fleet, Yamamoto always seemed one step behind during the Guadalcanal campaign which turned into a grinding battle of attrition which the Japanese could only lose. After presiding over the Japanese defeat at Guadalcanal, Yamamoto was killed in April 1943 when his aircraft was intercepted and shot down over the northern Solomons.

The officer in command of the Japanese carrier force during most of the Guadalcanal campaign including the battles of Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz was Vice Admiral Nagumo Chuichi. Though he had no background in aviation, Nagumo was appointed in April 1941 to assume command of the Kido Butai. His command style was marked by overconcern with detail, a lack of decisiveness and extreme reliance on his staff. In spite of this, he led the Japanese carrier force to a series of victories from Pearl Harbor through the Indian Ocean Raid in April 1942. At Midway, Nagumo’s luck ran out. Condemned by a faulty operational plan from Yamamato’s Combined Fleet staff and sloppy tactical planning by his own staff, Nagumo’s lack of aggressiveness was a notable factor in the Japanese defeat during which all four of his carriers were sunk. After the battle, he pleaded with Yamamoto to be given a chance to gain revenge, and Yamamoto relented. During the Guadalcanal carrier battles, Nagumo’s caution was even more pronounced.

Nagumo’s chief of staff was Rear Admiral Kusaka Ryunosuke. He had an extensive background in naval aviation, but he was not an aviator and did not possess a deep knowledge of aviation. He was cautious and outspoken by nature, and his cautiousness must have reinforced Nagumo’s natural inclinations.

Rear Admiral Kakuta Kakuji was commander of Carrier Division 2. During the Midway battle, he led his force capably and covered the capture of two islands in the Aleutians, which turned out to be the only successful part of the entire operation. His performance at Santa Cruz showed him to be an aggressive officer.

Other important command figures included Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake, who commanded the Advance Force after the Combined Fleet’s reorganization after Midway, which actually included Nagumo’s force. A member of the so-called “battleship clique,” he was also known for his aggressiveness. Though he performed well at Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz, in November at the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, his botched tactics helped lose that pivotal battle.

Rear Admiral Abe Hiroaki was commander of the Third Fleet’s Vanguard Force. He was familiar with carrier operations as he had been in charge of the heavy cruisers in the Kido Butai since the beginning of the war. Following Santa Cruz, he was in charge of the bombardment force at the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November where his mission was defeated and he lost the first Japanese battleship of the war. As a consequence, he was forced to resign from the IJN in disgrace.

Rear Admiral Hara Chuichi, commander of Cruiser Division 8, was assigned to command the detached carrier strike group at the battle of Eastern Solomons. He had been commander of Carrier Division 5 at Pearl Harbor and the battle of the Coral Sea.

Carrier Shokaku was commanded by Captain Arime Masafumi who took command on May 25. He was noted for his extreme aggressiveness and did not hesitate to challenge Nagumo. He later died as a rear admiral leading strikes against American carriers in October 1944. Zuikaku was commanded by Captain Nomoto Tameki who assumed command on June 5. The captain of carrier Junyo was Okada Tametsugu. As was customary in the IJN, carrier captains were not aviators.