The carrier force

The United States Navy began the Pacific War with a total of seven carriers. After Pearl Harbor, the carrier task force became the primary fighting unit of the Pacific Fleet. Three of the seven carriers began the war assigned to the Pacific Fleet. Fortunately for the Americans, none was present at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The three Pacific Fleet carriers, Lexington, Saratoga and Enterprise, were soon joined by Yorktown in early 1942 and later by Hornet. The last prewar-built carrier to move into the Pacific was Wasp. After flying British fighters into the island of Malta in the Mediterranean in April and May 1942, she arrived in the Pacific in June 1942.

The two carriers of the Lexington class were the largest in the world at the start of the war. Lexington was sunk at Coral Sea. Saratoga was commissioned in 1927 after being converted from a battlecruiser, and displaced 48,500 tons. She had a top speed of 33.5 knots, but since she was the longest ship in the world, she was difficult to maneuver under attack. She had a disappointing war record going into the Guadalcanal campaign since she was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in January 1942 and thus missed the battles of Coral Sea and Midway.

The three-ship Yorktown class proved to be a very successful design. These 20,000-ton ships were large enough to permit the incorporation of protection against torpedo attack. A 4in. side armor belt was fitted over the machinery spaces, magazines and gasoline storage tanks. Vertical protection was limited to 1.5in. of armor over the machinery spaces. At Midway, Yorktown took a beating from torpedoes and bombs in excess of the expectations of her designers before finally succumbing. The primary design focus of the class was to provide adequate facilities to operate a large air group efficiently. This design emphasis, combined with the practice of operating a deck park of aircraft, meant that American carriers routinely embarked more aircraft than their Japanese counterparts.

Hornet joined the Pacific Fleet in April and had a short career before being sunk at Santa Cruz in October. The ship is shown here in May wearing her Measure 12 (modified) camouflage scheme which she wore her entire Pacific Fleet career. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Yorktown class also mounted a heavy defensive armament to counter air attack. This class represented some of the first US Navy ships equipped with the new 5in./38 dual-purpose guns that proved to be the best long-range antiaircraft weapons of the war. Four 1.1in. quadruple mounts were placed fore and aft of the island and 24 .50-cal. machine guns were originally fitted for close-in protection. By October 1942, the ineffective machine guns were being replaced by 20mm automatic cannons. Hornet received 32 20mm guns and Enterprise received 38. Both ships were also fitted with a fifth 1.1in. quadruple mount on their bows. Enterprise mounted the improved CXAM-1 radar. Hornet was initially fitted with the disappointing SC radar but then received a CXAM from the sunken battleship California. In service, the CXAM-1 was capable of detecting a formation of aircraft flying at 10,000ft at 70 miles.

During the Guadalcanal campaign, each American carrier embarked an air group of four squadrons. This composition was unchanged from the beginning of the war. One squadron was a fighter unit (designated VF and referred to as a “Fighting” squadron), two were equipped with dive-bombers and designated Scouting (VS) and Bombing (VB), and the last squadron was equipped with torpedo bombers (designated VT). By the time of the Guadalcanal campaign, the complement of a fighter squadron was authorized to increase from 27 to 36 fighters in response to experience at Midway where there were not enough fighters to fulfill combat air patrol (CAP) and strike escort requirements. Each of the dive-bomber squadrons had a nominal strength of 18 aircraft, and the torpedo squadron had 18 aircraft. The commander of the air group had his own aircraft, usually a torpedo bomber.

By August 1942, the prewar structure of the carrier air groups had fallen apart after the strain of eight months of war. Heavy losses at Midway and the wise policy of rotating veterans back to training commands had necessitated that the carrier air groups be rebuilt. Saratoga’s air group was composed of a collection of experienced squadrons. The fighter squadron was VF-5. Though the squadron had seen no combat action in the war, it possessed a number of experienced pilots. The dive-bombing squadrons included Bombing Squadron Three (VB-3) which had fought at Midway aboard Yorktown and destroyed Japanese carrier Soryu. Scouting Squadron Three (VS-3) had yet to see any combat action. The torpedo squadron was VT-8, rebuilt after it had been all but annihilated flying off Hornet at the battle of Midway.

Enterprise was the most storied carrier in the fleet. She had sunk carriers Kaga, Akagi and Hiryu at Midway. Her air group suffered heavy losses, and after the battle had to be rebuilt. For the first carrier battle in the Guadalcanal campaign, the fighter squadron was VF-6, which had experienced an almost total turnover of the veterans who fought at Midway. Bombing Six (VB-6) and Scouting Five (VS-5) from Yorktown comprised the dive-bomber squadrons. The torpedo squadron was VT-3, rebuilt after it was virtually destroyed at Midway flying off Yorktown.

When Enterprise returned to Pearl Harbor in September to repair battle damage from the Eastern Solomons, she received a new air group, Carrier Replacement Air Group Ten (CRAG-10). This unit was formed in March 1942 and was one of the first two replacement air groups. They were the first to have a number designation instead of their parent ship’s name. The group consisted of Replacement Fighting Ten (VRF-10) under the redoubtable Lieutenant-Commander James Flatley, Replacement Bombing Ten (VRB-10), Replacement Scouting Ten (VRS-10) and Replacement Torpedo Ten (VRT-10). The air group was commanded by Commander Richard Gaines. Each of the squadrons possessed a cadre of seasoned aviators and strong leadership, but was filled out by a majority of new officers directly from the training command. When the new air group went aboard Enterprise in October, it dropped the “replacement” and became Carrier Air Group Ten (CAG-10).

Hornet’s air group comprised VF-72, VB-8, VS-8 and VT-6. After a rough beginning at Midway, the air group was well trained, if lacking in combat experience.

The standard American carrier fighter from the start of the war through 1942 was the Grumman F4F Wildcat. The F4F-4 variant was a sturdy aircraft with a top speed of 278 knots (320 miles per hour). Its strengths were a heavy armament (six wing-mounted .50-cal. machine guns) and superior protection including self-sealing fuel tanks and armor for the pilot. However, when compared with its Japanese counterpart, it also possessed several key weaknesses. Its top speed was slightly less than the Zero’s and its climbing rate and acceleration were dramatically less. The Zero was also far more maneuverable. The Wildcat’s combat radius was limited to about 175 miles, making it the limiting factor in the attack range of an American carrier air group. Overall, the Wildcat was an inferior aircraft, but it could overcome its technical limitations with superior gunnery skills and better tactics.

The real stalwart of an American carrier air group in the early war period was the Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bomber. Given the troubles with American air-launched torpedoes, the Dauntless constituted the primary offensive punch of an American carrier air group. The Dauntless was a stable bombing platform, and, once into its steep bombing run, was very difficult to stop. It could carry two sizes of bomb. If a 1,000-pound bomb was carried, the maximum strike range of the Dauntless was 225–250 miles. A 500-pound bomb was carried on scouting missions, and in this role the Dauntless had a combat radius of up to 325 miles. The Dauntless had a top speed of 255mph and was rugged enough to withstand combat damage. Defensive armament included two .50-cal. machine guns firing forward and a twin .30-cal. machine gun fired to the rear by the radioman.

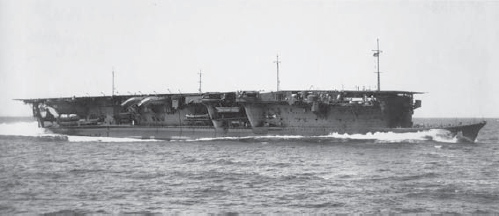

Saratoga pictured in 1942. The carrier was present at Eastern Solomons where her aircraft sank light carrier Ryujo, but damage from a submarine attack kept her out of Santa Cruz. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

A Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat aboard Enterprise in April 1942 in early war markings. The Wildcat possessed a heavy armament and was heavily protected, but remained inferior overall to the Zero. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bombers in early war markings on Enterprise during February 1942. Nicknamed “slow but deadly” by its crews, the Dauntless constituted the primary striking power of American carrier air groups during 1942. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

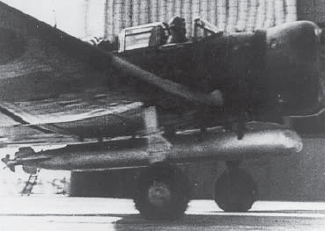

The new addition to the air group by August 1942 was the Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bomber which replaced the obsolescent Douglas TBD-1 Devastator. The new Avenger was such an improvement from the Devastator that American commanders were still learning to exploit its capabilities. Executing a torpedo attack at low altitudes and at low speed was a perilous undertaking, but the rugged Avenger improved the chances of survival, if not success. The standard American air-launched torpedo remained the Mark XIII aerial torpedo which was unreliable. Aside from carrying a single torpedo, the Avenger could alternatively carry two 1,000-pound or four 500-pound bombs. The aircraft carried three defensive weapons – a .50-cal. machine gun in a dorsal turret, a forward-firing .30-cal. machine gun, and a rear-firing .30-cal. machine gun mounted ventrally. The combat radius of the Avenger was slightly greater than that of the Dauntless.

The biggest question still facing American admirals in August 1942 was whether or not to concentrate their available carriers. Two schools of thought contended for primacy. The first, led by Fletcher, believed that carriers should be operated in the same formation to enhance mutual support and protection. This would allow for the massing of fighters and even escorts to increase the defensive power of the task force. This is what Fletcher had done at Coral Sea. At Midway, Fletcher’s single carrier fought separately from Spruance’s other two carriers; Yorktown was too far away for effective support and was lost.

The opposite view was held by most other commanders, including most of the aviators and the all-powerful King. They believed that carriers should be separated by 15–20 miles and operated in single-carrier formations. Doing so would decrease the likelihood that a single Japanese search aircraft could find both groups, and therefore increased the possibility that one group could evade attack. Aviators believed that operations by more than two carriers in the same formation were too unwieldy. At Eastern Solomons, Enterprise and Saratoga did not operate together, and Saratoga escaped being attacked. Aviators attributed this to the distance between them, but Fletcher believed (accurately) that it was because of the effective fighter defense.

Kinkaid agreed with the separation school. Halsey also shared this view. Halsey took the concept further and advocated a tactic in which carriers would be concentrated until they suspected or detected a Japanese strike to be imminent, at which time they would separate to a distance twice that of the prevailing visibility. This would reduce the possibility of the Japanese strike spotting both formations.

By the Guadalcanal campaign, the TBF-1 Avenger was the standard torpedo bomber in American carrier air groups. A TBF-1 is shown here dropping a Mark 13 torpedo. At this point in the war, the Mark 13 was unreliable, but after these problems were finally addressed, the Avenger became a formidable ship killer. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

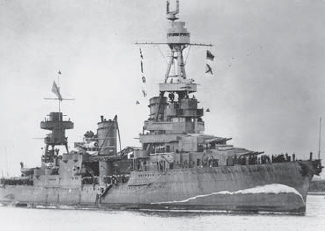

Northampton was typical of the heavy cruisers employed in carrier escort duty. She is shown here in August 1941. She was one of the few ships fitted with a CXAM radar before the war. The ship and her radar performed well at Santa Cruz. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

At Santa Cruz, neither concentration nor a more extreme separation tactic was employed. The two groups were operated only 10 miles apart. This was the worst of both alternatives. It was too far away to allow concentration of CAP or escorts, and not far enough away to confuse the Japanese. It was also far enough away to complicate further the coordination of operations, especially given the requirement to operate in radio silence or under conditions of bad communications which seemed to be the norm for 1942.

A continuing weakness of the US Navy’s carrier force in 1942 was its difficulty in conducting coordinated air operations. Even at the victory at Midway, lack of coordination was especially prevalent. According to existing doctrine, once a suitable target was located, each carrier launched its entire air group, minus any fighters withheld for defense. This could be a lengthy process since it required the launch of two deckloads of strike aircraft. After launch, different aircraft speeds and altitudes of the various squadrons made it difficult to maintain a joint formation. Once bad weather and poor communications were thrown into the mix, the invariable result was confusion with squadrons ending up proceeding separately to the target. Doctrine did not even provide for the coordination of multiple air groups from different carriers even if they had the same target.

In the second part of 1942, the Americans were putting together the pieces for creating a formidable capability to defend their carriers against Japanese air attack. However, by the time of Santa Cruz these capabilities were not fully mature. The salient American tactical advantage during the early carrier battles was the possession of radar. All carriers and some escorts were equipped with radar which could provide warning of the approach of a large group of aircraft from some 70 miles away. This provided enough warning to marshal a fighter defense. However, early radar was unable to ascertain the exact height of incoming aircraft which precluded truly efficient fighter control.

Fighter direction was still a rudimentary art in August 1942. Problems with radio discipline hampered communications with fighters aloft and the few channels available often made control impossible. The performance of fighter defense at Coral Sea was poor, but at Midway progress was evident. At Santa Cruz, the fighter direction officer (FDO) on Enterprise was assigned as lead FDO for the entire task force. On October 23, just before the battle, Enterprise’s FDO, Commander Leonard Dow, who had been Enterprise’s FDO since before the war, transferred to Halsey’s staff. Halsey said later that he debated this move, but Dow’s replacement was the former head of the Fighter Direction School on Oahu, Lieutenant-Commander John Griffin. Despite Griffin’s undoubted theoretical knowledge, he possessed no combat experience. Enterprise’s radar officer was also new, and, to make matters worse, other key radar personnel had also just transferred off the ship. During the battle, both Enterprise and Hornet experienced flaws with their radars.

Once Japanese aircraft broke through the fighter defenses, they still faced the antiaircraft guns aboard the carrier and its escorts. American antiaircraft defense doctrine placed the carriers inside a ring of escorts to increase the weight of antiaircraft protection. American carrier task groups maneuvered as a single entity under air attack to keep formation and maintain antiaircraft protection to the carrier. American ships were equipped with some of the best antiaircraft weapons of the Pacific War. The standard long-range air defense gun during the war was the 5in. dual-purpose gun. The 5in./38 gun was fitted aboard the Yorktown-class carriers and escorting destroyers. It was also reaching the fleet in increasing numbers aboard the new class of light antiaircraft cruisers and the new battleships. It was an accurate gun and possessed a high rate of fire. The escorting cruisers were equipped with the older 5in./25 gun, which was still a capable weapon but had a shorter range. Later in the Guadalcanal campaign, the 40mm quadruple mount began to enter service on the North Carolina- and South Dakota-class battleships; at Santa Cruz, South Dakota had four of the new mounts. This was the most effective intermediate-range antiaircraft weapon of the war. For short-range antiaircraft protection, two weapons were employed in 1942. The 1.1in. machine cannon was a four-barreled, water-cooled system that could deliver a rate of fire of 140 rounds per minute per barrel. However, in service it proved disappointing because of continual jamming problems. Last-ditch air defense protection was provided by an increasing number of 20mm Oerlikon automatic cannons. However, with an effective range of 2,000 yards or less, these weapons were unable to destroy Japanese aircraft before they dropped their weapons. Though American antiaircraft fire by itself could not prevent an attack by determined Japanese aviators, it did take an increasingly significant toll on attacking Japanese aircraft. This culminated at Santa Cruz where antiaircraft fire took a toll on attacking aircraft equal to that of defending fighters.

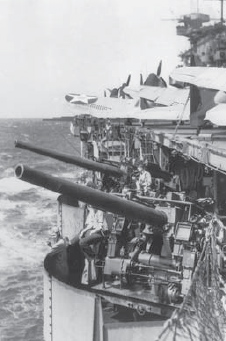

This is the port quarter 5in./38 gun battery aboard Enterprise pictured in February 1942. The Enterprise and her sister ships each carried eight of these formidable weapons which were considered to be the finest long-range antiaircraft weapons of their day. Above the guns are Dauntless dive-bombers. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The standard long-range gun on heavy cruisers and the older carriers was the 5in./25; one is shown here on cruiser Astoria in 1942. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

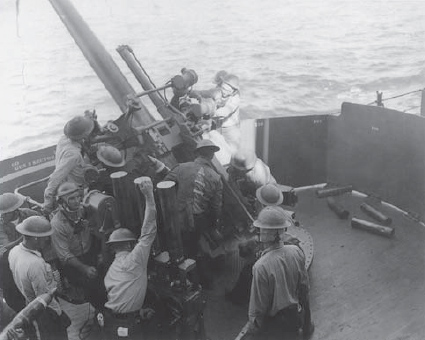

The primary intermediate-range antiaircraft weapon through most of 1942 was the 1.1in. quad mount. This one is on Enterprise. Persistent jamming problems reduced the effectiveness of the weapon. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

20mm Oerlikon mounts began to replace the ineffective .50-cal. machine guns throughout the fleet in 1942. These are on carrier Yorktown before she was sunk at Midway. Since they did not require a power supply and were optically guided, these guns were easily placed anywhere with a clear field of fire. They were to take a deadly toll of Japanese aircraft throughout the war. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Intelligence

For the first two carrier battles of the war, American commanders had been well served by their intelligence sections. While intelligence had provided advance notice of major Japanese moves, it was by no means omniscient. This was shown by the fact that at Coral Sea the path of the Japanese carrier force into the Coral Sea was unknown and even at Midway the full scope of the Japanese order of battle was unknown, though intelligence on the order of battle and intended operations of the Kido Butai was very accurate.

Going into the first carrier battle of the Guadalcanal campaign, Ghormley and Fletcher did not possess solid knowledge of Japanese intentions or their order of battle. Available intelligence was confusing; so unclear was Fletcher about Japanese intentions that he detached one of his three carriers for refueling just before Eastern Solomons. The problem was complicated when on August 18 the IJN changed its radio call signs temporarily making analysis of Japanese radio traffic impossible. As late as August 21, the Pacific Fleet intelligence officer assessed that the Kido Butai was in Japan.

The standard US Navy long-range search plane of 1942 was the PBY Catalina. On occasion, it was also used as a bomber, but only at night and not as shown in this photograph. These aircraft, operating from Espíritu Santo and tenders in the Santa Cruz Islands gave the Americans an important advantage in the two carrier battles fought off Guadalcanal which was squandered owing to communication problems. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The intelligence with which Nimitz and Halsey were provided before Santa Cruz was not only vague, but turned out to be incorrect. The Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, DC provided a weekly assessment of the dispositions and intentions of Japanese naval units. In the weeks before Santa Cruz, these had been consistently inaccurate. Nimitz was able to warn Halsey of a major impending Japanese operation as early as October 17, but the estimates he provided of Japanese force dispositions were off the mark. Of the five Japanese carriers, Nimitz’s intelligence officer placed only Shokaku and Zuikaku in the South Pacific. The two carriers of Carrier Division 2, Hiyo and Junyo, were still assessed to be in Japanese home waters. In reality, they had arrived in Truk on October 9. Light carrier Zuiho was unlocated. This faulty intelligence provided the basis for Halsey’s risky plan of sending his two carriers into action well north of Guadalcanal.

The new Kido Butai

The Japanese carrier force had taken severe losses in both ships and aircraft before the Guadalcanal campaign began. For the first phase of the war from Pearl Harbor until May 1942, losses had been relatively light. This changed at Coral Sea in May 1942. During this first clash with American carriers, light carrier Shoho was sunk and all 18 of her aircraft lost, but worse was the damage to Shokaku and the loss of 69 aircraft from the air groups of Shokaku and Zuikaku. The bomb damage to Shokaku and heavy losses to Zuikaku’s air group kept both carriers from participating in the Midway operation in June.

Losses in the disastrous Midway operation totaled four carriers with all 248 of their embarked aircraft. As heavy as these losses were, at least aircrew losses were not correspondingly heavy. Still, 110 aircrew were lost and the survivors were exhausted after six months of non-stop operations.

The losses and lessons learnt from Midway required a wholesale reorganization of the IJN’s carrier force. On July 14, the Combined Fleet was reorganized and the carriers placed in the paramount position for future operations. The First Air Fleet became the Third Fleet which was now clearly established as the Combined Fleet’s primary offensive force. The Second Fleet, composed of fast battleships, heavy cruisers and destroyers, was to be used as an advanced screen for the carriers. This force was deployed between 100 and 150 miles ahead of the carriers. In this position, they would be in place to finish off any American ships crippled by air attack. Another benefit was that it would siphon off some of the American air attacks intended for the Japanese carriers.

Even after the heavy carrier losses at Midway, the Japanese still retained five carriers suitable for fleet work with another soon to be completed. These six ships actually outnumbered the four carriers remaining to the Pacific Fleet, but the aircraft capacity of the six Japanese carriers totaled about 300 aircraft, smaller than the total number of aircraft carried aboard the four American ships. The new Third Fleet was composed of two carrier divisions. The centerpiece of the rebuilt Kido Butai was the two carriers of the Shokaku class, Shokaku and her sister Zuikaku. Formerly Carrier Division 5, this was renamed Carrier Division 1 and was under Nagumo’s direct control. Shokaku had been under repair at Kure since May 17 and would be ready by late July. Joining the two big carriers was the converted light carrier Zuiho. The old Carrier Division 4 was now redesignated as Carrier Division 2 and was placed under the command of Rear Admiral Kakuta. It included the converted carriers Junyo and Hiyo and the light carrier Ryujo. Hiyo was due to be completed in July.

Shokaku in August 1941. When launched, Shokaku and her sister ship were the most powerful carriers afloat possessing a fine combination of striking power, speed and protection. Since neither was present at Midway, both survived and became the backbone of the Kido Butai during the Guadalcanal campaign. (Yamato Museum)

Zuikaku in 1941 showing the elegant lines of her design. Abaft the small island are two downward-sloping funnels which vented exhaust gasses. Zuikaku was the last prewar fleet carrier to be lost; she was sunk by carrier air attack at the battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. (Yamato Museum)

Third Fleet also received an increased number of supporting ships, addressing one of the lessons learned at Midway. These included battleships Hiei and Kirishima, and four heavy cruisers (Kumano, Suzuya, Tone and Chikuma). The two ships of the Tone class were the most modern Japanese heavy cruisers and carried a large number of float planes (five) which were useful for scouting missions.

The only surviving fleet (heavy) carriers from before the war were Shokaku and Zuikaku. These were large (26,675 tons standard displacement) ships with an aircraft capacity of 72 aircraft. They were fast (34 knots) and well armed with antiaircraft weapons. Unlike other Japanese carriers, they proved able to sustain battle damage as proven when Shokaku took three 1,000-pound bombs at Coral Sea and survived. In August, Shokaku received a No. 21 radar with an effective range of about 60 miles against a group of aircraft. She was the first Japanese carrier to receive radar. The Shokaku class was the finest carrier afloat at the start of the Guadalcanal campaign.

The other two heavy Japanese carriers were the two units of the Hiyo class. These were not designed as carriers, but were conversions from the largest passenger liners in the Japanese merchant fleet. They were requisitioned in February 1941 and converted into carriers. Junyo was completed in time to see action at Midway, but Hiyo was just entering service when the Guadalcanal campaign began. Each carried up to 48 aircraft making them useful additions to the carrier force, but they were not as effective as design-built carriers. Their maximum speed was 26 knots, barely adequate for fleet work and their level of protection was minimal. Their machinery, destroyer-type boilers mated to merchant turbines, proved troublesome. This was demonstrated when engine problems forced Hiyo to miss Santa Cruz.

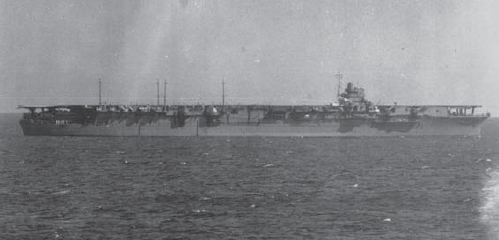

This is a photo of Junyo taken on June 3, 1944. Her appearance was similar in October 1942, but she lacked the radar mounted on the island. This view clearly shows her lineage as a merchant ship, but also demonstrates her large size which enabled her to carry a relatively large air group. (Yamato Museum)

Light carrier Ryujo dated from 1933. The ship was designed with a capacity of 48 aircraft but carried fewer in service. Ryujo was an unsuccessful design with a relatively slow speed and unsatisfactory aircraft handling arrangements which impeded flight operations. On the other hand, light carrier Zuiho was more successful in service though she was a conversion from a submarine tender.

Each of the Shokaku-class carriers embarked an air group with three squadrons. These air groups were named after their parent ships and were permanently assigned to the ship. The composition of the air groups changed in light of the Midway experience. The fighter squadron was increased to 27 aircraft as was the number of dive-bombers. In order to increase the overall number of aircraft that could be carried, the number of torpedo bombers was reduced to 18. The reduction of the number of torpedo aircraft also reflected the Japanese belief that these aircraft were more vulnerable. The aircraft complement of the two Hiyo-class carriers reflected the same priorities as the Shokaku-class ships. Each of these converted carriers carried 48 aircraft broken down into 21 fighters, 18 dive-bombers, and nine torpedo planes. The aircraft of the two light carriers reflected their new air defense mission. Ryujo carried 24 fighters and nine torpedo planes while Zuiho carried 21 and six, respectively.

The post-Midway reorganization was still under way when the Americans landed on Guadalcanal. For the first Japanese offensive against the Americans in the South Pacific, Yamamoto could bring only Carrier Division 1 into action with Shokaku, Zuikaku and Ryujo. To put 177 aircraft on these ships, the Japanese had to strip Hiyo, Junyo and Zuiho of fighters and dive-bombers making them 29 fighters and 16 dive-bombers short of establishment (though they did retain an extra 15 torpedo planes). Carrier Division 2 would take until September to achieve readiness, and thus was totally available by the time of Santa Cruz in October.

Ryujo after her second major refit in 1936 to correct stability problems. As designed, Ryujo was to carry 48 aircraft, but she carried far fewer in service. The ship was assigned to secondary duties in the first part of the war because of her small aircraft capacity and inefficient layout which hampered flight operations. At the battle of the Eastern Solomons, she carried only 24 Zero fighters and nine Type 97 attack planes. (Yamato Museum)

Light carrier Zuiho in December 1940 after her conversion was completed. Zuiho proved a useful addition to the Kido Butai. She earned the reputation as a lucky ship and was not sunk until October 1944 at the battle of Leyte Gulf. (Yamato Museum)

Carrier Division 2 arrived at Truk on October 9 after completing training in the Inland Sea. Both ships had a full-strength air group with the exception of Junyo which was deficient by three fighters. Both of the fighter squadrons contained a large number of veterans, and the attack squadrons were also led by experienced aviators.

Japanese carrier air groups remained superior to their American counterparts throughout 1942 in two areas – fighters and torpedo bombers. The Japanese dive-bomber was also a capable design, but was inferior overall to the American Dauntless. The Japanese used a design philosophy that stressed maneuverability and range. This gave Japanese carrier aircraft superior range compared with their American counterparts, but this was achieved at the cost of inferior protection.

The standard Japanese carrier fighter was the A6M Type 0 (called “Zero” by both sides). The Zero had met the Wildcat for the first time at Coral Sea and its superiority was acknowledged even by the Americans. It possessed exceptional maneuverability, great climb and acceleration, and a powerful armament. However, this performance was largely achieved by lightening the airframe as much as possible which translated into a lack of armored protection and self-sealing fuel tanks.

An A6M Type 0 carrier fighter being launched from Zuikaku on January 20, 1942 during the strike on Rabaul. The fine lines of the Zero are evident in this scene. Possessing excellent range and a good armament, the Zero was the outstanding fighter in the early part of the Pacific War. (Yamato Museum)

Type 99 carrier bombers spotted aboard a Japanese carrier early in the war. Despite its ungainly appearance, the Type 99 was a deadly accurate bombing platform and would take a heavy toll on Allied shipping during the war. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The Japanese called their dive-bombers “carrier bombers.” The standard carrier bomber through 1942 was D3A1 Type 99 Carrier Bomber (later codenamed “Val” by the Allies). The Type 99 was well designed for conducting precision dive-bombing attacks. It was a deadly weapon in the hands of an experienced pilot as proven by the fact that it had sunk more Allied ships than any other Japanese aircraft up to this period of the war. Though rugged enough to withstand up to 80-degree dives, it did not carry self-sealing fuel tanks and carried a smaller bomb load than the Dauntless.

The real edge possessed by Japanese air groups during the Guadalcanal campaign was the fact that they possessed a viable torpedo attack capability. This was provided by the B5N2 Type 97 Carrier Attack Plane. Later codenamed “Kate” by the Allies, this aircraft was primarily designed to act as a torpedo bomber, but could also carry bombs. The Type 97 was inferior in performance to the new American Avenger, but what made the Japanese torpedo bomber so formidable was that it could employ a dependable air-launched torpedo. This was the Type 91 Mod 3 Air Torpedo which contained a 529-pound warhead and was capable of traveling at 42 knots for up to 2,000 yards. The importance of the combination of the Type 97 and its reliable and effective torpedo cannot be understated. Both at Coral Sea and Midway, this combination gave Japanese air groups an effective ship-killing power not possessed by American carriers of the day. At both battles, once an American carrier was struck by an air-launched torpedo, it did not escape destruction. However, the Type 97 (like any torpedo bomber) was required to fly relatively low and slow toward the target making it very vulnerable to enemy fire. This weakness was exacerbated by the fact that the aircraft had exchanged range for a lack of protection.

The Japanese carrier force changed its doctrine and tactics after Midway. In each of the two carrier divisions, the two heavy carriers were seen as offensive platforms while the light carrier was to be used primarily as a provider of fighters for CAP. Despite heavy losses, an important strength of the Kido Butai was its ability to conduct coordinated, large-scale, air operations. Going into the Guadalcanal campaign, the Japanese had shown they were able routinely to orchestrate air attacks by multiple carriers. Unlike their American counterparts, Japanese carriers did not operate as single tactical units. Rather, all carriers in a carrier division acted as a single unit and routinely operated their aircraft as a single tactical unit. This meant that, during the course of 1942, the Japanese were able to handle their carrier aircraft in a manner far superior to that of the Americans. Japanese offensive air operations were better coordinated, and because they did not depend on a single carrier, were usually larger.

A type 97 carrier attack plane landing on Shokaku in March, 1943. During the Guadalcanal campaign, the Type 97 was approaching obsolescence, but the aircraft was still a formidable threat. (Yamato Museum)

A Type 97 carrier attack plane taking off with its primary weapon, the Type 91 Mod 3 Air Torpedo. This weapon had a 529-pound warhead and a top speed of 42 knots which made it a formidable ship killer. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Another lesson from Midway was the vulnerability of torpedo bombers. During the first part of the war, Japanese tactics when attacking heavily defended naval targets were to attack simultaneously with dive and torpedo bombers to overwhelm the defenses and minimize losses to the more vulnerable torpedo bombers. Going into the Guadalcanal campaign, the Japanese decided to hold their torpedo aircraft in reserve until the dive-bombers had crippled the American carriers. This tactic proved unsuccessful at Eastern Solomons, and by the time of Santa Cruz the Japanese had returned to their more traditional combined-arms attack with simultaneous dive and torpedo bomber attacks.

These tactics had a probability of success as long as they were being executed by highly trained and aggressive aircrew. By August 1942, Japanese carrier air groups still possessed these types of aircrew in abundance. Overall, they possessed a higher level of training and experience than American air groups of the period.

Throughout the first phase of the war, at Coral Sea, and to a lesser degree at Midway, the Kido Butai had shown itself to be a formidable offensive weapon. This was in accordance with the IJN’s overall emphasis on the offensive. However, though the Japanese were demonstrably proficient at massing and coordinating offensive air power, they also demonstrated an inability to defend their carriers properly. This weakness was laid bare at Midway when lack of radar, poor CAP doctrine, weak antiaircraft capabilities and weaknesses in damage control combined to destroy four carriers.

At Midway, the most glaring weakness was a lack of early warning. Each of the four Japanese carriers sunk during the battle had been surprised by American dive-bombers taking them under attack. The principal reason was the total lack of radar on any Kido Butai ship during the battle. Shokaku was equipped with radar before Eastern Solomons. However, since the equipment was still new in fleet use, it did not provide complete coverage. It was used with some success at Santa Cruz and the employment of the Advance Force tactics which acted as an air defense picket greatly diminished the likelihood that Japanese carriers would be totally surprised as at Midway.

Direction for Japanese fighters performing CAP was still a problem. The Japanese used a system of standing CAP with additional fighters on alert to scramble as needed. True fighter control was impossible because Japanese aircraft radios were virtually worthless making it impossible to control aircraft once airborne.

All Japanese carriers were equipped with long-range (5in. guns) antiaircraft weapons and short-range 25mm guns. The 5in. gun was the Type 89 dual mount, but the effectiveness of this weapon was handicapped by inadequate fire-control systems and a doctrine which called for barrage fire against quickly maneuvering targets. The Type 96 25mm gun served as the short-range weapon and was fitted on all carriers and escorts in both double and triple mounts. Unfortunately for the Japanese, the selection of this weapon proved to be a poor choice since it possessed a number of weaknesses. These included an inability to handle high-speed targets (it could not be trained or elevated fast enough and its sights were inadequate), excessive vibration and muzzle blast which affected accuracy, and an inability to maintain high rates of fire because of the need constantly to change magazines. Because the gun fired such a small shell (.6 pounds), it lacked stopping power against the rugged American Dauntless and Avenger. As a result, American aircraft losses to antiaircraft fire were low.

The weakness of Japanese shipboard antiaircraft gunnery meant that the most effective form of defense from American air attack was skillful maneuvering. When Japanese carriers came under air attack, the ability of the carrier’s captain to execute timely maneuvers was critical. The escorts around the carrier were expected to allow it to execute whatever maneuvers were required. Radical maneuvering made it more difficult for the carrier’s gun crews to generate correct fire-control solutions for accurate antiaircraft fire. The primary threat from American carriers was posed by the accurate Dauntless dive-bomber; on the other hand, the American Mark 13 air-launched torpedo could easily be defeated by timely maneuvers since its top speed was only 33 knots. The faster Japanese carriers had the speed simply to outrun the torpedo.

Intelligence

The Japanese had only a vague notion about the intentions and operations of American carriers. They had no ability to read American codes, but analysis of radio traffic did provide indications of impending operations. For example, when Enterprise departed Pearl Harbor in mid-October following repairs after Eastern Solomons, the Japanese correctly deduced she was headed for the South Pacific. The best sources of information on major American fleet movements were spotting reports from long-range flying boats from the Shortlands. In addition, float planes from battleships and cruisers performed tactical scouting and performed well in this role. Japanese analysis of the basic American carrier order of battle was weak. By Santa Cruz, the Japanese believed that the Americans had already produced a second and third generation of carriers with the same names of carriers previously sunk which prevented them from even understanding how many carriers the Americans had available for operations.

All strengths as of 0500hrs, August 24, 1942

( ) denotes operational aircraft

Third Fleet (Main Body) (Vice Admiral Nagumo Chuichi aboard carrier Shokaku)

Carrier Division 1 (Nagumo)

Carrier Shokaku (Captain Arima Masafumi)

Shokaku Air Group Commander (Lieutenant-Commander Seki Mamoru)

Shokaku Carrier Fighter Unit 27 (26) Type 0

Shokaku Carrier Bomber Unit 27 (27) Type 99

Shokaku Carrier Attack Unit 18 (18) Type 97

Carrier Zuikaku (Captain Notomo Tameteru)

Zuikaku Air Group Commander (Lieutenant-Commander Takahashi Sadamu)

Zuikaku Carrier Fighter Unit 27 (25) Type 0

Zuikaku Carrier Bomber Unit 27 (27) Type 99

Zuikaku Carrier Attack Unit 18 (18) Type 97

Destroyers (from Destroyer Divisions 10 and 16): Kazegumo, Yugumo, Makigumo, Akigumo, Hatsukaze, Akizuki

Vanguard Force (Rear Admiral Abe Hiroaki in Hiei)

Battleship Division 11

Battleships: Hiei, Kirishima

Cruiser Division 7

Heavy cruisers: Kumano, Suzuya

Cruiser Division 8

Heavy cruiser Chikuma

Destroyer Squadron 10

Light cruiser Nagara

Destroyers from Destroyer Divisions 4 and 17: Nowaki, Maikaze, Tanikaze

Detached Carrier Strike Force (Rear Admiral Hara Chuichi in Tone)

Light carrier Ryujo (Captain Kato Tadao)

Ryujo Air Group Commander (Lieutenant Notomi Kenjiro)

Ryujo Carrier Fighter Unit 24 (23) Type 0

Ryujo Carrier Attack Unit 9 (9) Type 97

Heavy cruiser Tone

Destroyers (from Destroyer Division 16): Amatsukaze, Tokitsukaze

Advance Force (Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake in Atago)

Cruiser Division 4

Heavy cruisers: Atago, Maya, Takao

Cruiser Division 5

Heavy cruisers: Haguro, Myoko

Destroyer Squadron 4

Light cruiser Yura

Destroyers from Destroyer Divisions 9 and 15: Kuroshio, Oyashio, Hayashio, Minegumo, Natsugumo, Asagumo

Seaplane carrier Chitose with 22 aircraft

Task Force 61 (Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher)

Task Force 11 (Fletcher)

Saratoga (Captain Dewitt C. Ramsey)

Saratoga Air Group (Commander Harry D. Felt) 1 (1) SBD-3

Fighting Five 27 (27) F4F-4

Bombing Three 17 (17) SBD-3

Scouting Three 15 (15) SBD-3

Torpedo Eight 13 (13) TBF-1

Utility Unit 1 (1) F4F-7

Heavy cruisers: Minneapolis, New Orleans, HMAS Australia

Light cruiser: HMAS Hobart

Destroyer Squadron 1

Destroyers: Phelps, Farragut, Worden, Macdonough, Dewey, Patterson, Bagley

Task Force 16 (Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid)

Enterprise (Captain Arthur C. Davis)

Enterprise Air Group (Lieutenant-Commander Maxwell F. Leslie)

Fighting Six 29 (28) F4F-4

Bombing Six 17 (17) SBD-3

Scouting Five 18 (16) SBD-3

Torpedo Three 15 (15) TBF-1

Utility Unit 1 (1) F4F-7

Battleship: North Carolina

Heavy cruiser: Portland

Light cruiser: Atlanta

Destroyer Squadron 6

Destroyers: Balch, Benham, Maury, Ellet, Grayson, Monssen

All strengths as of 0500hrs, October 26, 1942

( ) denotes operational aircraft

Support Force (Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake in Atago)

Advance Force (Kondo)

Carrier Division 2 (Rear Admiral Kakuta Kakuji in Junyo)

Carrier Junyo (Captain Okada Tametsugu)

Junyo Air Group Commander (Lieutenant Shiga Yoshio)

Junyo Carrier Fighter Unit 20 (20) Type 0

Junyo Carrier Bomber Unit 18 (17) Type 99

Junyo Carrier Attack Unit 7 (7) Type 97

Carrier Hiyo and destroyers Isonami and Inazuma detached October 22 for Truk

Battleship Division 3

Battleships: Kongo, Haruna

Cruiser Division 4

Heavy cruisers: Atago, Takao

Cruiser Division 5

Heavy cruisers: Maya, Myoko

Destroyer Squadron 4

Light cruiser Isuzu

Destroyers from Destroyer Divisions 15, 24 and 31: Kuroshio, Oyashio, Hayashio, Kawakaze, Suzukaze, Umikaze, Naganami, Takanami, Makinami

Third Fleet (Main Body) (Vice Admiral Nagumo Chuichi aboard carrier Shokaku)

Carrier Division 1 (Nagumo)

Carrier Shokaku (Captain Arima Masafumi)

Shokaku Air Group Commander (Lieutenant-Commander Seki Mamoru)

Shokaku Carrier Fighter Unit 22 (18) Type 0

Shokaku Carrier Bomber Unit 21 (21) Type 99

Shokaku Carrier Attack Unit 24 (24) Type 97

Carrier Zuikaku (Captain Notomo Tameteru)

Zuikaku Air Group Commander (Lieutenant-Commander Takahashi Sadamu)

Zuikaku Carrier Fighter Unit 21 (20) Type 0

Zuikaku Carrier Bomber Unit 24 (22) Type 99

Zuikaku Carrier Attack Unit 20 (20) Type 97

Light Carrier Zuiho (Captain Obayashi Sueo)

Zuiho Air Group Commander (Lieutenant Sato Masao)

Zuiho Carrier Fighter Unit 19 (18) Type 0

Zuiho Carrier Attack Unit 6 (6) Type 97

Heavy cruiser: Kumano

Destroyers (from Destroyer Divisions 4 and 16): Amatsukaze, Hatsukaze, Tokitsukaze, Yukikaze, Arashi, Maikaze, Teruzuki, Hamakaze

Vanguard Force (Rear Admiral Abe Hiroaki in Hiei)

Battleship Division 11

Battleships: Hiei, Kirishima

Cruiser Division 7

Heavy cruiser: Suzuya

Cruiser Division 8

Heavy cruisers: Chikuma, Tone

Destroyer Squadron 10

Light cruiser Nagara

Destroyers from Destroyer Divisions 10 and 17: Akigumo, Makigumo, Yugumo, Kazegumo, Isokaze, Tanikaze, Urakaze

Task Force 61 (Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid)

Task Force 16 (Kinkaid)

Enterprise (Captain Osborne B. Hardison)

Carrier Air Group 10 (Commander Richard K. Gaines) 1 (1) TBF-1

Fighting Ten 34 (31) F4F-4

Bombing Ten 14 (10) SBD-3

Scouting Ten 20 (13) SBD-3

Torpedo Ten 9 (9) TBF-1

Battleship: South Dakota

Heavy cruiser: Portland

Light cruiser: San Juan

Destroyer Squadron 5

Destroyers: Porter, Mahan, Cushing, Preston, Smith, Maury, Conyngham, Shaw

Task Force 17 (Rear Admiral George D. Murray)

Hornet (Captain Charles P. Mason)

Hornet Air Group (Commander Walter F. Rodee) 1 (1) TBF-1

Fighting Seventy-Two 38 (33) F4F-4

Bombing Eight 15 (14) SBD-3

Scouting Eight 16 (10) SBD-3

Torpedo Six 15 (15) TBF-1

Heavy cruisers: Northampton, Pensacola

Light cruisers: San Diego, Juneau

Destroyer Squadron 2

Destroyers: Morris, Anderson, Hughes, Mustin, Russell, Barton

Task Force 64 (Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee)

Battleship: Washington

Heavy cruiser: San Francisco

Light cruisers: Helena, Atlanta

Destroyers: Aaron Ward, Benham, Fletcher, Lansdowne, Lardner, McCalla