6: Renewal and Reaction, 1880–1940

I. Literary Renewal, 1880–1893

Ton Anbeek

The Movement of 1880

At the end of the nineteenth century Dutch literature in the Netherlands was radically transformed by the appearance of the so-called Generation of 1880. Of course, even radical transformations never come completely out of the blue. Impulses toward change had been discernible before, but they remained isolated and lacked wider resonance; one example is Busken Huet’s novel Lidewyde, which was discussed in the previous chapter. The strength of the men of 1880 (women played virtually no role in the movement) was that they formed a united front in breaking with the literary conventions that had dominated Dutch literary life until then.

Significantly, they called the magazine that was to be their mouthpiece The New Guide (De nieuwe gids). Just as in 1837 The Guide (De gids) had asserted itself in opposition to an older periodical, so this new generation wanted to inject new life into literature — and not only into literature, for the magazine’s subtitle was “Magazine for Literature, Art, Politics, and Science.” The first year’s issues devoted more pages to political commentary than to all its poetry and creative prose combined. Their politics soon became radicalized, with socialists and anarchists campaigning against the heartless liberalism that dominated the political stage. The prosperous middle classes became the target of the left-wing contributors to the new magazine, just as poets and prose-writers pilloried the sedate literary taste of the liberal bourgeoisie. For the first few years of the periodical’s existence, artistic and political reformism seemed to be in unison — until both sides realized that while they might be fighting the same enemy, they were striving for very different ideals.

The Movement of 1880, with its two-pronged program of artistic and political renewal, may be seen as symptomatic of the rapid change that Dutch society was undergoing at the end of the nineteenth century. Later, one member of the Generation of 1880, the greatest poet among them, Herman Gorter, looked back at that change, having in the meantime converted to Marxism. After 1870, Gorter observed, the Netherlands saw the development of large-scale capitalism and the growth of an “industrial proletariat.” Amsterdam changed from an eighteenth-century town with a craft-based economy into an industrialized capitalist metropolis:

That transformation of things was a transformation of people! New powers were harnessed, new beings were forged, and we were those new beings. Society was to be changed utterly, new and greater forces emerged, a new and greater happiness was on its way. . . . Not a moment passed without something of those new forces being implanted in us. They were social forces, forces that affect society and hence each individual, and so we were constantly surrounded by them. All our senses, our heart, our head, our hands, our sex were touched by them.60

Many of the changes from this tumultuous period had a direct impact on literary history. In 1863 a new type of secondary school, the Higher Public School (Hoogere Burger School or HBS), was introduced alongside the traditional gymnasium. The new school was far more practically oriented than the gymnasium, which with its classics-based program prepared pupils for university. New sections of the population were now given the chance of further and higher education. It is striking that a number of members of the Generation of 1880 should have attended the HBS, suggesting a link between the emergence of a new literature and the emancipation of the bourgeoisie.

Yet however much political revolutionaries rubbed shoulders with their literary counterparts in the pages of The New Guide, the magazine owes its fame largely to the new poetry that emerged from it. The central figure in this trend was the former HBS pupil Willem Kloos (1859–1938). Kloos first caused a stir when he wrote an introduction to the posthumous poems of his friend Jacques Perk (1859–81) after the latter’s untimely death. In fact, Kloos did not simply publish the poems; he arranged and “improved” them as he saw fit. In this way he refashioned Perk to fit the desired image: that of a trailblazer for the new poetry and thus in effect for Kloos’s own work. Kloos’s “Introduction” (1882) amounted to a manifesto proclaiming the principles of a new poetry.

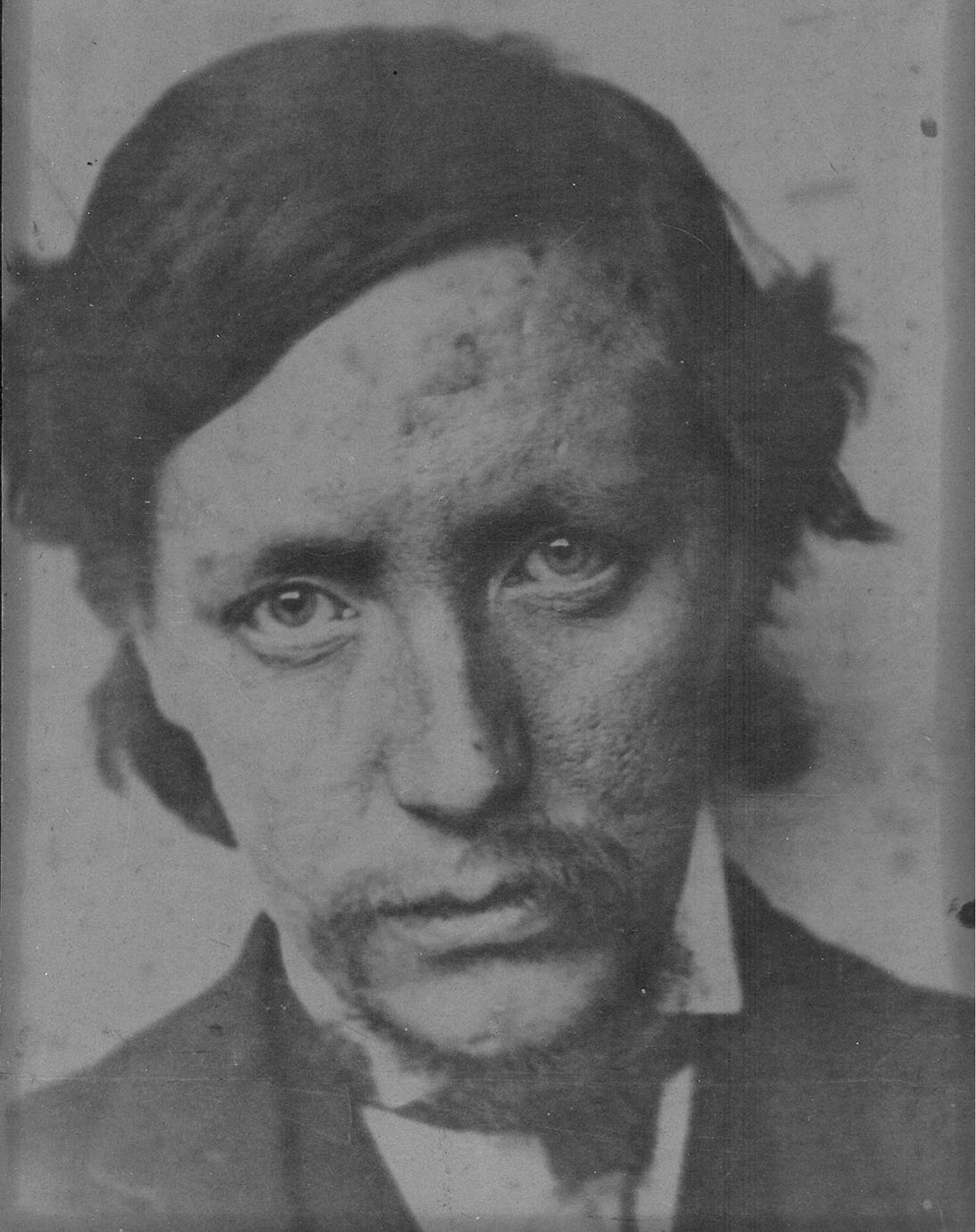

Willem Kloos. The Hague, Literary Museum.

In his preface Kloos explicitly states which poets served as his models; he names Shelley, Keats, and Wordsworth — in short, the English Romantic poets of over half a century before. Kloos’s stress on “emotion” is entirely in accord with the Romantic creed, as in Wordsworth’s celebrated definition: “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” Poets, Kloos maintains, can be recognized by the intensity of their emotions. He constantly alludes to traditional poets who mistook “sentimentality for feeling, conventional commonplaces for imagination, and an unruffled flow for deeper melodies.” He does not name names at this point, not wishing to make the introduction to the work of his late friend into a polemical pamphlet. His appeal to the English Romantics was meant to illustrate sufficiently what true poets were. This brings him to the following lyrical formulation:

Poetry is not some doe-eyed maiden who, lending us a hand along life’s path, teaches us with a smile how to tie a bouquet of flowers . . .: but a woman, proud and magnificent, . . . who turns the highest joy into the deepest suffering, but at the same time turns deepest suffering into the ecstasy of pain, presses the thorns into our forehead till we bleed, in order that the unique crown of immortality may blossom from it.

The poet who has the crown of thorns forced onto his head: the parallel with the figure of Christ is unmistakable. It reveals a characteristic trait of the kind of Romanticism that the Generation of 1880 embraced. During the early era of Romanticism, the period 1780–1830, we find various European adherents, including writers like Willem Bilderdijk, for whom religion and art are in fact one. But at a later stage a shift in emphasis takes place. Poetry is now no longer identical to religion: it replaces religion. In the Netherlands this new interpretation can be explained by the fact that Kloos and his followers were vehemently opposed to work that served the traditional bourgeois ideals of religion, virtue, and patriotism — the type of verse that had been churned out for decades by clergymen who were simply continuing their ministry in rhyme. To the Generation of 1880 such pious doggerel was anathema, and they worked hard to neutralize it.

The offensive gathered force with the appearance of The New Guide in 1885. That same year saw the publication of the collection Blades of Grass or Songs on Virtue, Religion and Patriotism (Grassprietjes of Liederen op het gebied van Deugd, Godsvrucht en Vaderland). The writer used the name Cornelis Paradijs (his real name was Frederik van Eeden). A “friend” of the author’s, writing as P. A. Saaije Azn. [saai = dreary], contributed an “Open Letter to the Writer,” which contains such paeans as “Your blades of grass will be as balm poured on the sore wounds inflicted on us by Naturalism, Socialism, and other such godless things.” Using the name Sebastiaan Slaap [slaap = sleep] Willem Kloos wrote a preface praising “the many excellent, first-rate poets in our country” whose lyre is ever at the ready to celebrate “religion, hearth and home, our native land, and the unforgettable House of Orange.” The collection is one long parody of the interminable offerings of the self-important clergymen poets, who are mocked in turn in “The Clergyman’s Song.” It is a classic example of a younger generation settling scores with a way of writing poetry that has become irrelevant.

Still in the same year, 1885, Kloos and Albert Verwey published a long poem, Julia, a Sicilian Tale (Julia, een verhaal van Sicilië), a verse epic cobbled together to fool the critics. Sure enough, some reviewers responded enthusiastically to the string of clichés. The authors claimed victory, having demonstrated that the critics had no understanding of poetry and were hence unfit to judge, as indeed the two practical jokers explained for good measure in a venomous brochure. These successful stunts brought the young revolutionaries the publicity they needed, and showed that their appearance on the scene was meant as a radical break with the dominant poetic tradition. As late as 1884 one of the principal representatives of that tradition, Nicolaas Beets, had been fêted nationwide on his seventieth birthday.

The new-style poet was not a clergyman; generally he had no profession at all. He was not even a practicing Christian. The Generation of 1880 put an end once and for all to the hitherto axiomatic relationship between religion and art. After 1885 art and religion were to be continually at loggerheads: Christian literature — that is, literature based on traditional Christianity — was marginalized and virtually disappeared. When Christian motifs do appear in the work of such later poets as P. C. Boutens, Martinus Nijhoff, and Gerrit Achterberg, they are used in entirely unorthodox ways. Hence secularization began much earlier in literature than in Dutch society as a whole, where the process only really gathered momentum in the course of the twentieth century.

Religion disappears from literature; or perhaps one should say that Christianity is ousted by a private religion? Jacques Perk’s poem “Deinè Theos” illustrates the point:

Beauty, o thou whose name shall hallowed be,

Thy will be done; thy kingdom let us see;

No other god but thou shall be adored on earth!

Beholding thee, a man’s life is complete:

If death’s power now brings him to defeat . . .

What matter? His joy’s of highest worth.

Keatsian worship of beauty, but on the model of the Lord’s Prayer. In a poem that comes close to blasphemy, Perk, the son of a clergyman, professed his new religion. It was Kloos who would most forcefully advocate the art-for-art’s-sake argument against the clergymen who wrote poetry for the sake of the edifying message. Another celebrated thesis of the Generation of 1880 — “form and content are one” — may also be seen in this light, as it offered an implicit challenge to the clergymen poets, for whom form remained secondary. In practice the slogan “form and content are one” meant that the poets paid great attention to sound effects that heightened the mood being evoked.

In one of his columns in the The New Guide Kloos arrived at a definition of art that found its way into all Dutch textbooks: art, he claimed, was “the supremely individual expression of the supremely individual emotion.” This definition, too, can be seen as a reaction to clergymen’s poetry. The traditional poets proclaimed generally recognized ideals; their individuality was mainly expressed through the presence or absence of technical ability, not through any exceptional, utterly personal feelings. Utilitarian art is by definition not art that strives after the personal.

This hostility to the socially oriented art of their predecessors may explain why Kloos and his fellow poets adopted only part of the legacy of English Romanticism. The rebelliousness of Shelley, who challenged the powers that be, found no echo among them — that would have brought them much closer to those contributors to The New Guide who supported social reform, like Frank van der Goes. Instead the new poet shut himself off from society, which anyway was incapable of understanding his unique sensibility. But even if he had jettisoned Christianity, he still cherished the illusion that his loneliness and suffering had only one parallel in human history: the passion of Christ. As such, he derived his grandeur indirectly from Christianity.

The social isolation of the new artists associated with the Generation of 1880 had far-reaching consequences, and not only for the fortunes of The New Guide, which witnessed an increasing antagonism between art-for-art’s-sake devotees and social reformers. Kloos and his associates turned their backs on bourgeois society. A comparison with the feeble flicker of Dutch Romanticism around 1830 is instructive here. At that time a number of young students in Leiden enthused over English and French Romanticism. But they were preparing to become clergymen and were to assume a respected position in society; Byronic attitudes were not conducive to such a calling. Nicolaas Beets, the most important of them, soon realized this and foreswore his “black period.” Kloos and his circle, who lived in a much more dynamic world, dared to defy social norms. The resulting tension between the new artist and the bourgeois world created a kind of bohemian class, with artists living from hand to mouth on the fringes of society. Both the break with Christianity and the break with the bourgeoisie represent radical changes in the history of Dutch literature — changes that in other European countries had taken place earlier.

The poetry of Kloos is one long lament for the loneliness of the sensitive heart. “The Man must die before the Artist can live,” he wrote. Pride in his own art alternates with pessimism at the great suffering from which art must spring. The artist stands alone and misunderstood in the world, as he pursues his cult of Beauty. Megalomania and humility are strikingly expressed in this sonnet:

Deep in my inmost thoughts a God I tower,

And in my inmost soul enthroned I sit,

King of myself, the world, by royal writ

Of my own strife and triumphs, my own power, —

And when the hosts of wild dark faces lower,

Advance and jeer, then fly, defeat admit

At my raised hand and crown so brightly lit:

Deep in my inmost thoughts a God I tower.

And yet, sometimes so endlessly I yearn

To put an arm around your limbs so dear

And sob out loud, with glowing heart displayed,

With pride and glorious calm to disappear,

Swamped at your lips beneath a wild cascade

Of kisses, where words would serve no turn.

The poem appears to sing the praises of the poet’s own autonomy, but in the sextet this sense of superiority gives way to the longing to submit to a higher power (the beloved). However a Kloos poem opens, it usually ends in a lament at the loneliness of the sensitive poetic soul. Suffering is the key word in his oeuvre. For his own and many later generations Kloos became the symbol of the tortured poet. And that is what he must have looked like: photos show us a somewhat disheveled appearance with strikingly pale eyes. He may have later become a respectable citizen (after a mediocre female novelist “saved him from drink and poetry”), but he retained the aura of a Dutch Verlaine, a doomed poet who found it hard to survive the brutal realities of life.

Although Kloos was the most prominent representative of the new poetry and poetics and so became the representative of the Movement of 1880, he was not the most important poet of his generation. That honor belonged — as Kloos himself recognized — to a man five years his junior, Herman Gorter (1864–1927). In many ways Gorter’s development is symptomatic of the evolution of literary life in general at the turn of the century. His debut marked him as both an original and a highly accomplished poet. He began not with sonnets but with a long epic poem that has since become a classic, May (Mei, 1889). His contemporaries were immediately captivated by the grandeur of the poem, with its seemingly effortless opening:

A newborn springtime and a newborn sound:

I want this song like piping to resound

that oft I heard at summer eventide

in an old township, by the waterside —

the house was dark, but down the silent road

dusk gathered and above the sky still glowed,

and a late golden, incandescent flame

shone over gables through my window-frame.

A boy blew music like an organ pipe,

the sounds all trembled in the air as ripe

as new-grown cherries, when a springtime breeze

rises and then journeys through the trees.

The same contemporaries were confused when a year later Gorter published his collection Verses (Verzen). If one of the main aims of the Movement of 1880 was an “emancipation of the senses,” the expression of an original sensory view of the outside world, Gorter’s collection showed that emancipation in its most extreme form.

Herman Gorter. The Hague, Literary Museum.

Verses (1890) is a key volume in the history of Dutch poetry. Together with the work of Guido Gezelle in Flanders, it signals the beginning of modern poetry. Whereas Kloos retained the strict form of the sonnet to shape his poetic suffering, Gorter set aside all the existing rules, marshaling rhyme, meter, and imagery to record his extraordinary sensations. It is no accident that it was precisely this collection that inspired Kloos’s celebrated slogan about poetry being the supremely individual expression of the supremely individual emotion. In Gorter’s Verses all the traditional constraints yield to the need to give voice to exceptional, highly subjective perceptions.

The collection contains a number of poems that are easily accessible and whose distinctive feature is their charming simplicity, as well as several wonderful love poems. But alongside these are lyric poems that attempt to express what had never before been put into words. “The trees undulate on the hills,” begins one poem, and who can help but be reminded of that other obsessive, Vincent van Gogh, who, like Gorter, colors nature with his own feelings? Compared with lines like these, Kloos’s imagery looks conventional and predictable, like his sentiments, forever revolving around the torments of an exalted ego. Gorter goes much further, and his emotions sometimes border on madness:

The tower’s face aloft

in the midst still grandly shows the hours,

imagine hours, hours, hours —

they suffocate,

these moments that grate,

laughter itching there

is too much to bear,

I suffocate

under this demented light grand momentary weight.

To convey this extreme sensation all the conventional rules of versification are thrown overboard. Line length is arbitrary, with occasional rhyme, and the meter is halting: prosody is being mocked. This poetry is so individual that it is difficult to characterize. Is it impressionist, since Gorter is attempting to express unique impressions in language? Or does it prefigure expressionism, since the landscape is infused with the poet’s soul? Literary historians call these poems “sensitivist,” following the term coined by the critic Lodewijk van Deyssel, who wrote of Verses that it was “a book to sob over.” For Van Deyssel, “sensitivism” meant impressionism taken to its furthest extreme. For later readers the affinity with expressionism is unmistakable.

Gorter’s language is as daring as his treatment of the rules of prosody is idiosyncratic. As a result, contemporary readers of Verses faced a novel problem that has become familiar to today’s poetry lovers, in that a rational approach to the language used is virtually impossible. Associations and guesswork are needed to divine a meaning apparently in flux. Here a late-nineteenth-century audience was given a taste of what would not erupt with full force until over a half a century later: poetry in which the reader was expected to make sense of the supremely personal associations of the idiosyncratic poem. Not surprisingly, most readers in 1890 were at a loss as to what to make of this lyricism.

In these poems Gorter evokes extreme sensations. He sometimes even seems to be on the verge of madness — here too a comparison with Van Gogh suggests itself. However, realizing the danger of abandoning himself to these frenzied sensations, he took a step back and chose the stable form of the sonnet for the poems he published in the following year, which have gone down in history as the “turning-point sonnets.” The turning-point referred not only to the verse form. Gorter had come to the conclusion that the truly great poets such as Homer and Dante owed their superiority to their coherent worldview. It meant the beginning of his search for a comparable intellectual foundation for his own poetry.

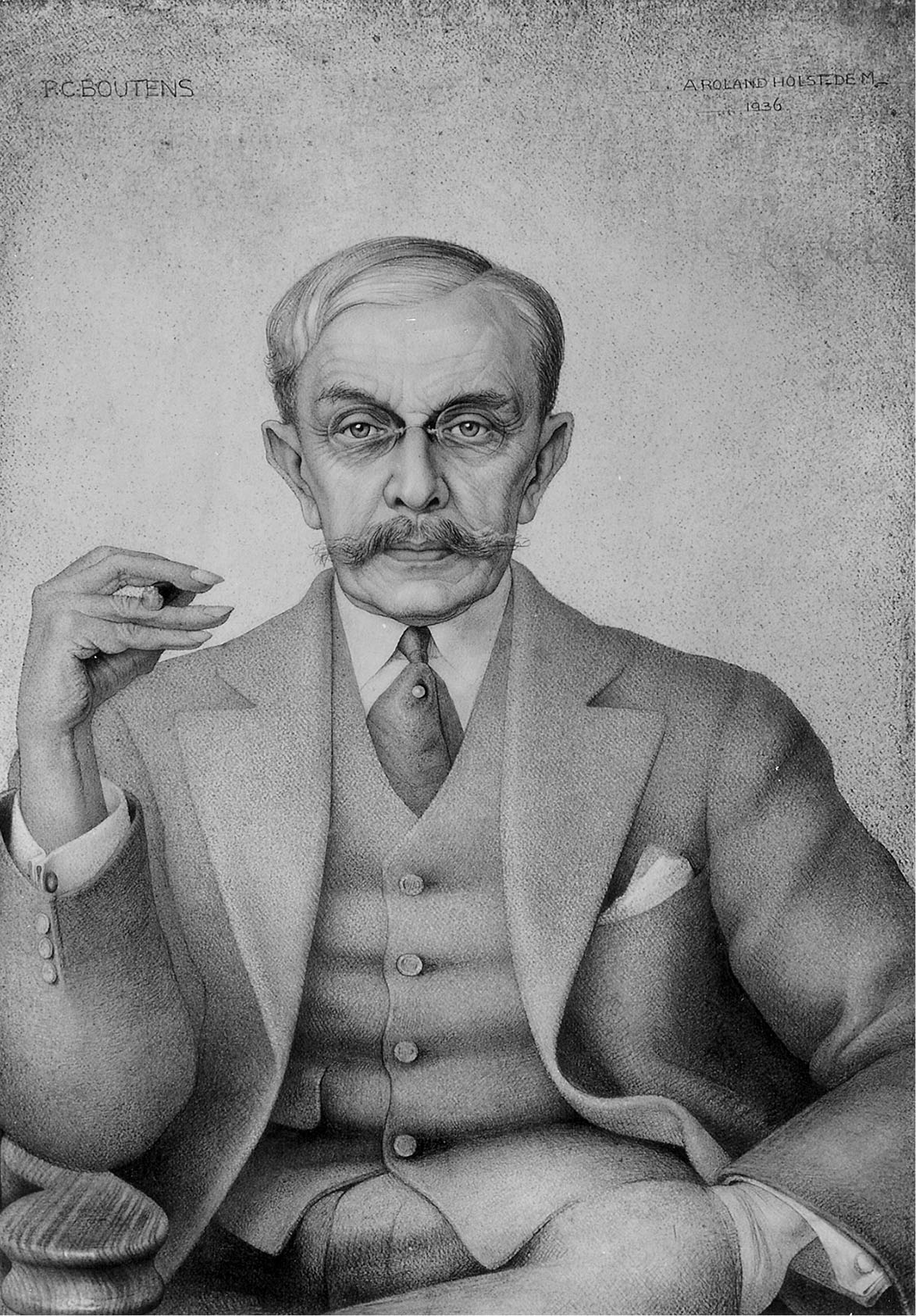

Lodewijk van Deyssel. The Hague, Literary Museum.

For a while he found a philosophical anchor in the work of Spinoza, a philosopher who had a great appeal for some of his contemporaries, such as Albert Verwey and Frederik van Eeden, who had turned their backs on Christianity but had not yet found a replacement. Unfortunately Gorter’s philosophical study did not produce any compelling poetry. He eventually concluded that he was “on the wrong side,” that is, on the side of capitalism. In 1897 he joined the newly founded Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP), the party that was to represent constitutional socialism in Dutch politics. This, however, soon proved too tame for Gorter. He began to advocate what he saw as a purer Marxism, which led to his joining smaller and smaller splinter groups. In his view even Lenin was not far enough to the left. Eventually his party became so small that it could no longer exercise any concrete influence on Dutch political life, whereas the socialists were increasingly inclined to participate in government.

Gorter’s conversion to “scientific” Marxism meant that henceforth his poetry, too, was harnessed to the class struggle, so that the Netherlands’ greatest poet subordinated his unmistakably sublime talent to politics. The step of course provoked widespread debate. Supporters and opponents judged Gorter’s transition according to their own political leanings, and Gorter’s reputation as a poet dipped sharply. Few critics or readers put the later epic poetry of the convert on the same plane as his debut May. Nevertheless the later work, particularly the shorter lyric poems, contains some superb lines.

The incomprehension with which Gorter’s defection was met in literary circles is not hard to understand. Just when poetry had finally freed itself from the yoke imposed by Christianity, it bowed to the dogma of Marxism! But although Gorter’s radical volte-face remained unique, his attempt to find a philosophical anchor was not uncharacteristic of the spirit of the 1890s. The short period of the uninhibited celebration of the senses was followed by a period of introspection. Submersion in the world of the senses is obviously not satisfying in the long run, at least not for Dutch poets. They lacked the foundation that Christianity had once offered, became disoriented in their intoxication, looked madness in the face and hastily took a step back. A need “for more style and certainty, a firmer direction and belief” (as the historian Johan Huizinga characterized the period), became apparent everywhere in the 1890s. Individualism proved a dead end, art for art’s sake no longer an adequate premise. The result was a series of great tensions within The New Guide, which never fully recovered from the crisis.

Quite early on there had been clashes between the five founding editors: Frederik van Eeden, Frank van der Goes, Willem Kloos, Albert Verwey, and Willem Paap. The last of these bowed out after only a year. The talented Albert Verwey (1865–1937) also departed fairly quickly, following a conflict with Kloos. An ideological confrontation with Frank van der Goes (1859–1939) proved equally inevitable. Van der Goes was a political activist who advocated progressive policies; later he became one of the founders of the SDAP, to which Gorter briefly belonged. Sooner or later a showdown with the advocates of art for art’s sake was inevitable.

The crisis was triggered by an article by Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932) in which his dislike of Van der Goes’s rationalism became evident. One of Van Eeden’s targets was a popular book by the American author Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, 2000–1887 (1888), in which this utopian thinker sketched a vision of a future society where equality ruled. As it happened, it was Van der Goes who had translated it (under the title In het jaar 2000). The rifts in the editorial board soon widened as a result of this vision of the future.

The great propagandist of the new prose, Lodewijk van Deyssel (1864–1952), adopted an extreme, Wilde-like position. Art, he claimed, being a luxury, cannot exist in an egalitarian society. When all incomes are the same there will be no room left for the luxury that is art. Consequently universal suffrage will be the death knell of “Personality and Intellect, Thought, Art, every exalted achievement of mankind up to now.” Van der Goes opposed the view of the gifted polemicist Van Deyssel with supreme sobriety and objectivity. But a full-scale conflict could no longer be avoided when Kloos joined the debate and stated bluntly: “Social reformers, in the nature of things, in the core of their being, are anti-artistic.” Kloos saw the notion of equality as an offshoot of “that accursed nuisance Christianity! We thought we had been freed from it for ever.” This outburst also stung the religiously inclined Van Eeden. From that moment the rift between the ivory-tower writers and those with more social awareness at The New Guide became unbridgeable.

By the end of the magazine’s seventh year, in 1892, each of the editors stood alone: Van Eeden with his religious humanism, Van der Goes as a Marxist theoretician, and Kloos with his anti-Christian elitism, supported by the polemical power of Van Deyssel. It is an irony of history that at the very moment that The New Guide had won the battle for literary power its editorial board disintegrated. The discussion on the place of art in society would continue to preoccupy young artists in subsequent years. Increasingly they abandoned the art-for-art’s-sake thesis of Kloos and Van Deyssel and searched for new anchors. Some found it in socialism or anarchism; others in Spinoza, in theosophy, which enjoyed great popularity at the time, or in Oriental religions. A few returned to that “accursed nuisance Christianity.” Gorter’s development from unbridled abandonment to the senses to doctrinaire Marxism is symptomatic of the artists’ search for a new ideology in the 1890s.

Naturalism in the Netherlands

In the late nineteenth century two questions determined whether or not one was a progressive artist. Do you like Wagner? And what about Zola? The latter enjoyed an unprecedented reputation in the Netherlands. Gorter put him on a par with Homer and Shakespeare — borrowing this ranking from Lodewijk van Deyssel, the propagandist of the new prose. No doubt Emile Zola played a decisive role in the development of Dutch literary prose. He was very widely read. In 1885 Busken Huet mentions in passing that each new novel by Zola attracted two thousand advance orders in the Netherlands. “Germinal is already among our compatriots’ favorite books.”

All the same, Zola owed a large part of his reputation to the controversial nature of his work. His novels seemed to offer everything that the Dutch most abhorred and hence devoured. They were raw, unrelenting, and intensely realistic — and that when far into the 1880s virtually all Dutch novels followed the virtuous, idealistic pattern, with noble heroes, a complicated plot with an edifying denouement, and preferably a deathbed reconciliation. Those narratives had little to do with realism, and of course the authors knew that perfectly well: realism was coarse. Realists flouted the constitution of nineteenth-century Dutch literature, which stipulated that art must offer the prospect of a better world. Critics toiled to safeguard the high moral level of Dutch prose.

Zola’s naturalism seemed to make a mockery of all these noble principles. Accordingly, critics responded with manifestos like this one (from 1880):

Much has been said for and against the modern way of writing and it will be quite some time before the last word is spoken on the subject, but for ourselves we shall always maintain that the ordinary reader, who is already surrounded by mundane and ugly things, must wish, at least when reading, to inhabit for a moment a different kind of environment; one may occasionally read out of curiosity a work in which a great literary talent gives us a photographic impression of real life, but we prefer to return as quickly as possible to something that really enthralls us and transports us to a more beautiful imaginary world.

One finds comparable statements of principle even in the writing of the first serious critics of Zola’s work. Yet gradually new ideas started to percolate into the practice of prose writing. Reviewers objected more frequently to improbable plots. Narrative convolutions became less acceptable. Instead books appeared with characters that were no longer extremely good or extremely bad. From action to greater character analysis — this would be one way of characterizing the development that began in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and subsequently accelerated under French influence.

This shift has been of great importance to the development of the Dutch novel down to our own day. What it meant in practice was that novels driven primarily by action and plot became marginalized. Suspenseful books were no longer seen as literature but as reading matter, like detective fiction or thrillers. Serious literature experienced a marked introspective turn, with every appeal to outward suspense dismissed as trivial.

Around 1880 the first Dutch advocates of naturalism appeared. Marcellus Emants (1848–1923), for example, in a preface to Three Novellas (Een drietal novellen, 1879), took a clear stand against the idealizing prose of his age. He condemned the wrong-headed criticism with which “sterile little idealists dare to dismiss even a masterpiece like L’Assommoir.” In 1879 it required some courage to call an offensive novel like Zola’s L’Assommoir (1877) unreservedly a masterpiece. Still, Emants’s great model was not Zola but the Russian realist Ivan Turgenev, on whom he published an admiring essay in 1880, calling Turgenev a pioneer “of that new movement in literature that aims, with science as a scalpel in its hand, to penetrate as deeply as possible into human nature, and in recording nature to keep more closely to truth than was the case with the moribund school of entertaining narrators.”

Emants’s comments show how at the end of the nineteenth century writers all over Europe began defending a new point of view, which stressed the need for truth in art. The writer was no longer to act as a Sunday school teacher but as an anatomist. Zola empathized with the new tendency and exploited it by presenting himself as its embodiment. He established a close link between literature and science. The analogy proved highly effective, because science, especially medical science, was making great strides during this period through Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and others. Hence Zola became the champion, and the most vociferous advocate, of a movement that was in fact much broader than he would have us believe. From the point of view of literary history Emants’s perspective on these developments may be more accurate. Nevertheless, Zola successfully claimed the leading role for himself, so that in the Netherlands and Flanders too he was seen — and denounced — as the prophet of the new literature, the devil incarnate.

Around 1885 a number of articles appeared in the Dutch press explaining and defending naturalism. In that year Frans Netscher published “What Does Naturalism Want?” a not very imaginative compilation of Zola’s ideas, hailing naturalism as “the literature of our scientific age.” At the same time the young Cooplandt (pseudonym of Arij Prins, 1860–1922) published a series called “The Young Naturalists.” Cooplandt was also the first to publish a collection of naturalist sketches with the significant title From Life (Uit het leven, 1885), sparingly told stories, sad to the point of bitterness. More interesting is another collection, which appeared a year later, again with a telling title: Life Studies (Studies naar het naakt model). Its author was Frans Netscher (1864–1923), Zola’s spokesman in the Netherlands, who had previously published some remarkable sketches under a pseudonym. Netscher’s work is less bleak than that of Cooplandt, its extensive evocations of atmosphere reminiscent of impressionist painting. That both pleased and annoyed a man anxious to play a decisive role in Dutch literary history: Lodewijk van Deyssel (1864–1952).

Lodewijk van Deyssel (pseudonym of K. J. L. Alberdingk Thijm), the son of a well-known Catholic writer and art critic, encountered modern French literature at a young age. As early as 1883, when he was nineteen, he stated jauntily that naturalism would be the art of the future: “Our generation recognizes only physics, so our Dante will have to be Mr. Zola.” Not long afterward, however, he deployed his considerable polemical talent against the man who had so loyally defended Zola. His article was given the terse title “On Literature (Mr. F. Netscher).”

In it Van Deyssel summed up his main objection in one of his inimitable turns of phrase: “Zola is the chicken that came and laid the egg called Netscher in the lee of the Dutch dunes.” Everything about Netscher seems to annoy Van Deyssel, who rejects the notion that naturalism is a body of teaching, a doctrine. On the contrary, Van Deyssel argues, naturalism is “anti-school, anti-teacher, anti-regimentation.” It has only one principle: “The artist should confront real nature and record the impression nature makes on him, that is to say on his own, unique, individual temperament, his artistic consciousness.” In this formulation the accent has shifted from objectivity to subjectivity, from science to temperament. Van Deyssel is unequivocal on this point: science must lead to art and art is always superior to science. Zola’s positivist pretensions are relegated to the background. Van Deyssel also refuses to take Zola’s supposed objectivity seriously. Beneath that so-called objectivity, he (quite rightly) hears the artist “lamenting and weeping.”

Van Deyssel’s real motives become clear in a passage in which he once again strongly qualifies Zola’s aims and in fact bids them farewell. Naturalism, he claims, will be succeeded by a new current. Indeed, anyone really wanting to raise the literature of his country to a higher level should not slavishly imitate an existing movement imported from abroad but strike out on a new path. Van Deyssel provisionally calls it “sensitivism.”

Van Deyssel’s ultimate aim, then, is a nationalistic one: to launch a Dutch art that, succeeding or following on from naturalism, will contribute something new to world literature — no more and no less. One could also put it less kindly. Van Deyssel had nothing to gain as a propagandist of naturalism after the pioneering work of Netscher, “that rehasher of Zola’s used ideas,” and hence he sought a new direction. But in so doing he again encountered Netscher, because some of Netscher’s stories undeniably prefigured sensitivism — and indeed had been lavishly praised by Van Deyssel before he knew that their author was Netscher writing under a pseudonym. Van Deyssel’s polemic against Netscher really served a different purpose: it cleared the way for his own prose, the novel A Love (Een liefde, 1887).

A Love appeared in the bookshops in January 1888. In the same year, between 17 June and 4 December, Eline Vere, the first novel by the young Louis Couperus (1863–1923) was published in installments in a Hague newspaper. Also in 1888 Marcellus Emants brought out his Mistress Lina (Juffrouw Lina). The breakthrough of the naturalist novel was a fait accompli.

For all their differences in setting and style these books display a number of striking similarities. In all three novels the main character is a hypersensitive woman, or as it was termed at the time, a woman of nervous temperament. In the first chapter of A Love we read of the periodic bursts of feverish excitement that sweep the protagonist Mathilde along. In Couperus’s novel the eponymous heroine is first mentioned as follows:

“What is the matter with her?”

“I don’t quite know. Nerves, I think.”

“She really ought not to give herself up to these fits. With a little energy she could easily get over that nervousness.”

“Well, you see, aunt, this nervousness is the modern bane of young women, it is the fin de siècle epidemic,” said Betsy, with a faint smile.61

Mistress Lina’s husband, a farmer, says of his wife: “That woman is eaten up with nerves and everything she does comes from stress.” Van Deyssel saw this portrayal of a nervous temperament as a typically naturalist trait. He wrote of Emants’s novel: “He has become more of a pure naturalist in the careful observation and recording of the neurosis in Lina’s system.”

These three over-sensitive women live among more level-headed characters who fail to understand them. In all three cases the protagonist’s high-flown expectations end in disillusion. Both Eline and Mathilde feel an intense longing for love, a feeling that is frustrated; Lina is convinced that she is highly esteemed by those around her, but this turns out to be an illusion. In two of the three novels the disillusion leads to a more or less voluntary death. Eline takes an overdose, Lina contrives to have her daughter throw her under an oncoming train and on the last page of A Love Mathilde becomes “just another respectable lady” — not an enviable fate.

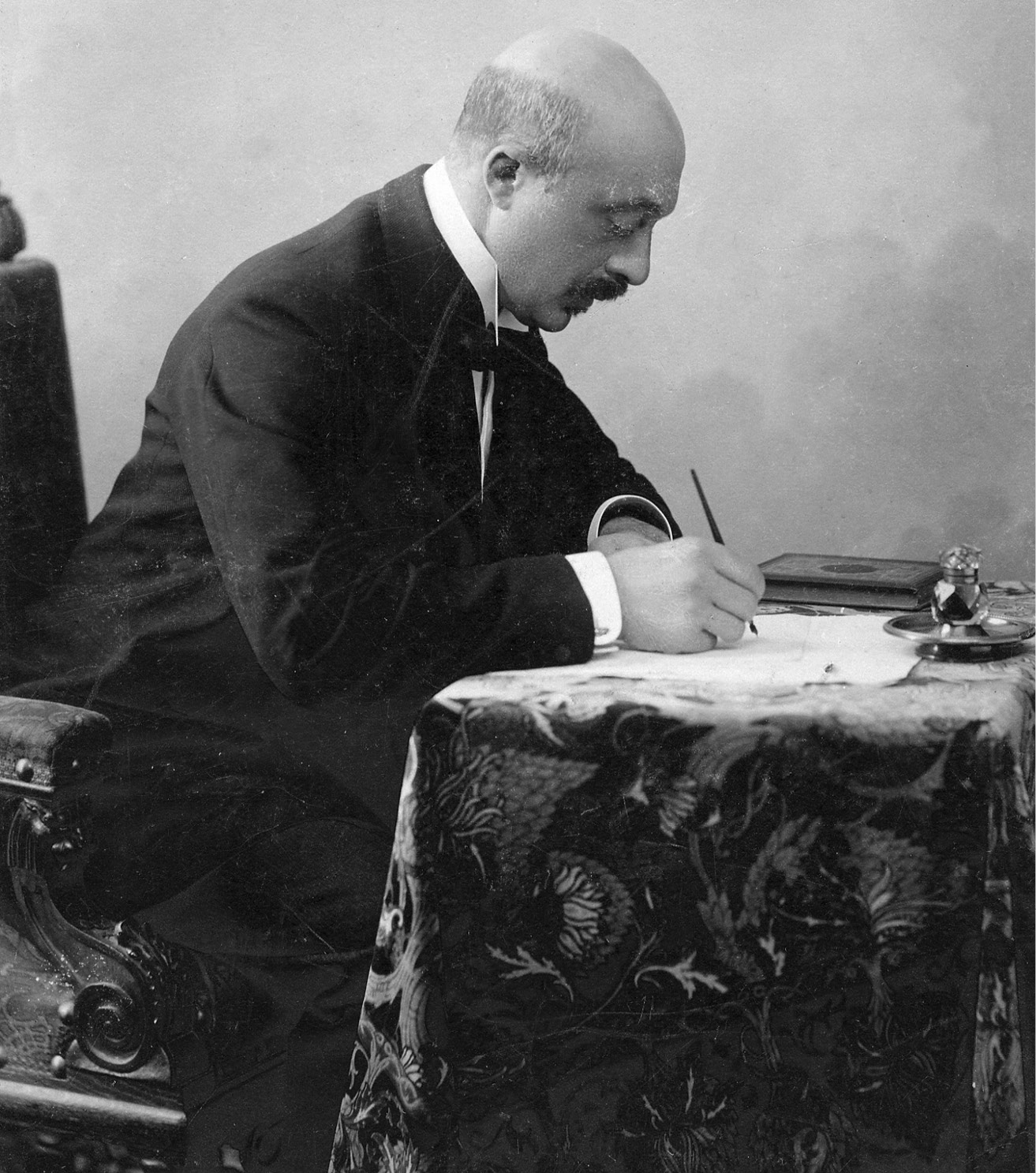

Louis Couperus. The Hague, Literary Museum.

In terms of both content and narrative technique all three novels contrast sharply with the traditional kind of idealizing prose. The old-fashioned novel often featured an omniscient narrator, who inspired confidence, took the readers (“dear lady readers”) by the hand, and guided them through the story. With the new prose there is no such guide. The narrator’s comments tend to be covert; they never use the inclusive “we.” Narratorial judgments on the moral value of individual characters are rare. Instead of standing outside or above the fictional world, the narrator rather inhabits the characters. There is consequently a marked increase in the number of passages using free indirect discourse. Van Deyssel, for instance, experiments with a stream of consciousness technique that was later to be fully exploited by James Joyce in Ulysses:

He read the Foreign News. That Emily Hartse, Mrs Berlage, was an attractive woman! He put the paper flat on the table and smoothed out the creases to be able to read it better. She was so lively, and had nice breasts too, he liked her. He read about the unpleasant business pending between the French and German governments . . . How on earth could she have chosen that fool Berlage!

A final similarity: in all three novels the laws of heredity have a disruptive effect. It is least marked in A Love. The wife looks like her mother, the husband takes after his father. It is more serious in the case of Mistress Lina. Upon hearing that her father died “in a madhouse,” the reader fears the worst. The weight of heredity is presented most subtly in Eline Vere. In the third chapter of Couperus’s novel we are already told that the heroine has the same “fine-strung temperament” as her father. Later a doctor, always the man of science in a naturalist novel and hence authoritative, arrives at this diagnosis:

But apart from that he saw something in Eline that might be called the fate of her family. Eline’s father had had it. Vincent [her cousin] had it. It was a psychic imbalance caused by her nerves, which were like the tangled strings of a broken and smashed harp.

Of course there are also differences between the three books, which can be traced back to the individual concerns of the separate authors. The story of Eline Vere — by far the best novel of the three — is that of an over-sensitive girl growing up in high social circles, a world of exquisite superficiality. In his first novel Couperus underlines the impact of hereditary factors, as was mentioned above. But there is more. There is also a mysterious force nudging Eline with invisible hands toward her doom, a force she cannot withstand. It is fate that drives her.

In Couperus’s second novel, which is indeed called Fate (Noodlot, 1890), heredity plays a much smaller part. The story exudes an oppressive atmosphere and culminates in a double suicide. It contains passionate scenes that recall Zola, including a realistically described murder, but despite these obvious naturalist features, the metaphysical destructive force of fate remains paramount. That force was to retain its devastating impact throughout Couperus’s work. Time after time he evokes characters who resist their destiny, in vain. His novels sometimes read like relentless chronicles of doom. In the course of the 1890s, influenced by the prevailing climate, the author tried to embrace a more optimistic view of life, the theosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson. One of the few positive forces in Eline Vere is embodied by an American character, but typically his influence comes too late. Despite flirting with all kinds of fairly whimsical philosophies Couperus remained generally a fatalist.

Not only does Couperus follow individual characters closely in their hopeless struggle with the forces of fate, but in some of his best novels he focuses on the downfall of a whole family. In The Books of the Small Souls (De boeken der kleine zielen, 1901–3), he describes “The Decline of a Family” — to quote the subtitle of Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks (1901), with which Couperus’s work bears comparison. We are again in The Hague, among the higher echelons of society, whose financial, moral, and physical decline is closely chronicled. In this masterpiece Couperus showed himself much more critical of these circles, with which he was intimately acquainted, than in his first novel, Eline Vere. Hypocrisy is a particular target: everything is subordinated to one’s good name, and empty conventions are supposed to give meaning to life.

The Hague has long been one of the most traditional cities in the Netherlands, partly because, as the seat of government, it houses foreign embassies and their diplomatic corps. There is another aspect of the city that is relevant to Couperus’s oeuvre. Many Dutch people returning from the East Indies and others with a colonial past settled in The Hague. Couperus, who spent part of his childhood in the colonial Dutch Indies (now Indonesia) — his father was a senior civil servant in the colonial administration — seems to have believed that an exotic origin pointed to a passionate temperament. In this respect he remained a naturalist: hereditary characteristics are a crucial part of one’s pedigree. It is therefore no accident that the crime of passion central to his best-known novel, Old People and the Things That Pass (Van oude menschen, de dingen die voorbijgaan, 1906), takes place in the colonies. The story again traces the disintegration of a well-to-do family, in this case through the fateful repercussions of a murder from the past. Although a naturalistic novel, Old People also highlights another theme that fascinated Couperus: decadence. Whereas in the Indies his characters appear highly emotional, the gray Dutch climate transforms them into indolent figures incapable of resisting the course of fate. It is precisely in the dissection of these unstable characters that Couperus shows his mastery, and herein resides the lasting value of a number of his novels.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Couperus’s work became well-known in the English-speaking world, thanks in no small part to his translator and former school friend Alexander Teixeira de Mattos, a naturalized Englishman who was completely bilingual. Teixeira de Mattos accompanied Couperus on his trip to England in 1921, where the writer was feted in literary circles.

Such success was not to be the lot of Couperus’s fellow-townsman Marcellus Emants. Emants’s most acclaimed novel, A Posthumous Confession (Een nagelaten bekentenis, 1894), departs from the usual naturalist pattern in that it is written not in the third but in the first person. It describes the life history of a man, Willem Termeer, who presents himself explicitly as a degenerate. In the usual naturalist way, Termeer sees his life as determined by the sins and shortcomings of his ancestors:

In those crystal-clear, sober moments when I discerned my past stretching out behind me like a series of links forged together by necessity, and saw this chain run onward to the furthest horizon of my future, I began to understand that my awkwardness, my lack of courage and perseverance, my want of feeling, my bent toward the forbidden, were nothing but the poisonous blossoms of seeds germinating in my ancestors. The roots stretched behind me into closed-off lives, therefore I would never be able to eradicate them.62

In other words, the heredity thesis serves him as an alibi for all the negative qualities he discerns in himself. As the son of a father who late in life, after “his passion has subsided,” married a loveless woman, Termeer cannot help being an emotional cripple. His gaucheness and timidity constantly thwart his attempts to relate to women, and so he resorts to paying for sex. His half-hearted attempts to find a role in life are equally unsuccessful. Being wealthy, he is free to devote himself to daydreaming and dissipation, but that brings no satisfaction. But then the tone changes. Like his father, Termeer finally marries a woman he cannot handle. She finds consolation of sorts with a neighbor, a former clergyman. Termeer looks on sardonically as this defender of morality and self-control tries to seduce his wife, and draws his own conclusion, which is that so-called normal people are in fact the worst hypocrites. They bandy fine words about but scarcely believe in them. Society is based on an absurd comedy. Termeer may be degenerate but he regards himself as no worse than the “so-called normal people,” just more honest. Emants’s choice of a marginal figure as a protagonist may have been inspired by Russian fiction, which he knew well; Gogol’s Diary of a Madman (1835) and Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864) may have been his models.

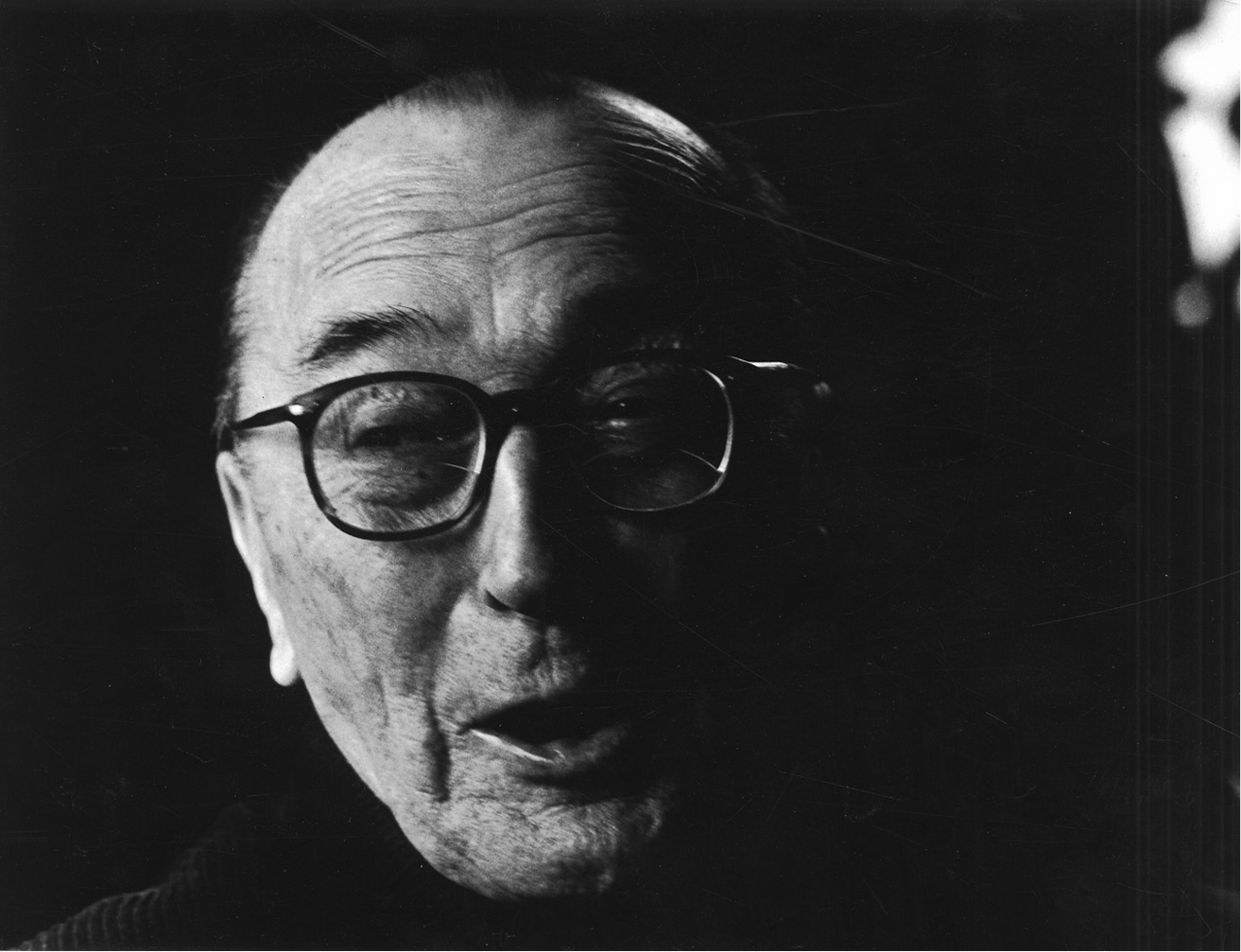

Marcellus Emants. The Hague, Literary Museum.

In Emants’s work a disappointment in love often leads to a disenchanted view of society in general. This is what happens to a young lawyer in the novel Initiation (Inwijding, 1901). Under the influence of his love for the woman he keeps, he briefly toys with militant ideas quite alien to his deeply conservative environment and goes so far as to defend a socialist. But eventually he opts for the security of his class. He lacks the strength to continue thinking and acting for himself. Like Couperus’s Books of the Small Souls Emants’s novel, subtitled “Hague Life,” paints an unforgiving picture of the upper middle classes. Both books are imbued with a sharply critical view of existing social relations, and in this respect both Couperus and Emants are followers of Zola’s, whose comment “What blackguards gentlemen are” (Quels gredins que les honnêtes hommes) recurs several times in Initiation.

As a novelist Lodewijk van Deyssel pales beside Couperus and Emants. His work consists mainly of embryonic sketches and ideas; he realized only a tiny proportion of his innumerable plans. Nevertheless, his influence on Dutch prose was considerable — though not always in a positive sense, at least in the view of later observers. Van Deyssel’s A Love was the first Dutch naturalist novel to be published, but, as was mentioned above, while the youthful writer was working on his first work he was already distancing himself from naturalism — with an ambivalent book as a result.

Three-quarters of the novel is devoted to describing the meeting and subsequent collision of two temperaments. Mathilde, whose solicitous father has given her a protected upbringing, is a hypersensitive girl who imbues reality with Romantic ideas acquired from her reading. One day Joseph enters her life, an eligible suitor who gains her father’s consent. Joseph, an otherwise unremarkable businessman, feels the time has come to end his bachelor existence and make a good match. He puts an end to his unrestrained womanizing, but on the evening of the day of his proposal he is so aroused that he meets up with an old girlfriend. The relationship between the two disparate main characters is bound to end in disappointment. Joseph thought he was marrying a spirited wife who would bring him prestige, but finds himself with a sickly stay-at-home. Because Mathilde’s expectations were unrealistically high, the down-to-earth Joseph is soon toppled from the lofty pedestal on which she had placed him. Each had seen the other as a fantasy figure, and the sober truth leaves both of them disillusioned. Joseph consoles himself with the maid, Mathilde with another child.

All in all A Love tells a banal story. Van Deyssel simply recorded the “physio-psychological process” of the clash between two temperaments in a naturalist manner, as Kloos put it. But the outline of the story does not do justice to the novel. In the controversial thirteenth chapter the factual record recedes into the background and a new kind of writing suddenly erupts. For page after page we are privy to Mathilde’s perceptions and sensations. Her fevered vision is rendered in such sentences as: “The purple turned blue-black in the sky, the purple and violet went browny-black, greeny-black, gray-black.” What Van Deyssel was trying to do here was paint in words. The chapter represents impressionism in language, always rather tiring to read since the writer has to evoke with a series of adjectives what a painter can show at a stroke. This long chapter is totally out of proportion to the rest of the book, as Van Deyssel later admitted. It is as though once he had found his new style he did not know how to stop.

A Love shocked and delighted its readers. Critics were irritated by certain risqué expressions and offended by the — in fact fairly veiled — treatment of female sexuality. “Brothel literature,” one reviewer declared. But prurient readers must have been seriously disappointed by the interminable descriptions of the thirteenth chapter, which was precisely the part that the avant-garde greatly admired.

Van Deyssel developed his experiments in various prose pieces, to the point of incomprehensibility. He was putting into practice the view of art that he had previously dubbed “sensitivism.” He found this art in Gorter’s Verses of 1890 and consequently acclaimed them (Gorter, in turn, had carefully read Van Deyssel’s critical prose.) He devised a system in which he distinguished a series of graduated stages: from observation to sensation. This sensation, “the supreme existential moment,” he defined in mystical terms: it takes us “into the reality of the higher life.” By the mid-1890s Van Deyssel was trying to develop a personal form of mysticism based on increasingly intense sensual experience. As early as 1891 he described his own evolution as “From Zola to Maeterlinck.” It is no accident that his quest for a new certainty should have brought him to the Francophone Belgian symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck, the writer who seemed to personify the quest for a higher dimension.

Though Van Deyssel was the first Dutch naturalist to leave naturalism behind, his contemporaries continued to see him as the movement’s champion. As the most acute critic of his generation Van Deyssel remained influential, and his prose experiments had a great impact — perhaps an inhibiting one, since almost all Dutch naturalists, following the thirteenth chapter of A Love, indulged in écriture artiste, or “fine writing,” succumbing collectively to the misconception that a writer can paint with words and use the dictionary as his palette (in the words of the historian Johan Huizinga). The result is not the colorful image that impressionist paintings present but a plethora of adjectives that obscure rather than illuminate.

One naturalist who remained unaffected by the vogue for écriture artiste was P. A. Daum (1850–98), who worked as a journalist in the Dutch East Indies throughout the 1880s. Dissatisfied with the kind of fiction that appeared in newspapers (“boarding-school reading,” he called it), he wrote a story in installments for his own paper. It met with a warm reception, and by the end of the century Daum had published ten or so novels that still fascinate with their unerringly exact descriptions of colonial society. Van Deyssel praised his first books but later rejected them as insufficiently artistic and too journalistic — a capital crime in the eyes of Dutch literary critics, then and now.

Although Daum’s sober prose differs from the aesthetic style the naturalists in his homeland strove for, he is still a naturalist. He learned much from Zola, whose novels he often praised in reviews. What annoyed Daum about colonial literature as it existed at the time was the lack of realism, particularly in the stilted dialogues and stark characterization. A person is never either completely good or completely bad, he said, echoing Zola. In his novels he aimed to give a lifelike portrait of Dutch East Indies society. The protagonists of his novels display weaknesses that eventually prove their undoing: addiction to gambling, dissipation, or religious fanaticism; in this respect his last novel, Aboe Bakar (1894), is very topical.

The novel Ups and Downs in Indies Life (“Ups” en “Downs” in het Indische leven, 1892), which paints a splendid picture of colonists who amass quick profits and subsequently meet disaster, features the only figure in Daum’s fiction whose behavior is determined by hereditary factors. He is a suicide, whose poignant death is one of the most powerful scenes in the first part of the novel. The second part is less strong, tending in parts toward old-fashioned idealizing prose. This literary hesitancy is one of the ambiguities of this intriguing author — both a exponent and a merciless chronicler of the colonial society he described.

The most striking feature of Dutch naturalism, apart from écriture artiste, is a predilection for nervous temperaments. Avant-garde writers had the whole of reality to choose from for their subject matter, yet they concentrated stubbornly on the neuroses of upper-class men or (more often) women. The fact that the upper middle classes were targeted by Dutch naturalists may have contributed to the emergence of a rift in reading patterns at the end of the nineteenth century. Just as clergymen poets wrote for and were in turn read by their parishioners, male and female novelists before 1888 produced literature that was read mainly by middle-class women — the higher orders read French and the men were too busy. These ladies found little appeal in prose that no longer offered them model characters or edifying endings. What good were the sordid lives of marginal neurotics to them? What is more, the increased openness in sexual matters made such novels “unsuitable” for respectable lady readers. The result was that the new prose initially had almost no readership; Eline Vere, a chaste book, is an exception. Readers continued to prefer the old historical novels of Jacob van Lennep and Geertruida Bosboom-Toussaint. Only when the rough edges of naturalism had worn away did the new novel find a popular audience.

Flemish Naturalism

The last quarter of the nineteenth century was a period of change in Flanders too, mainly because of the rapid pace of industrialization. However, literary renewal was a long time coming. Indeed, up to 1875 there was general apathy, causing one literary historian to speak of a “golden age of genial narrow-mindedness.” An inhibiting factor was undoubtedly the continuing use of French by large parts of the middle classes and certainly the grande bourgeoisie and the nobility.

Unsurprisingly, French-speaking Belgium was much quicker to respond to naturalism. Signs of innovation were visible from an early date in journals such as Current Affairs (L’Actualité, 1876–77), which in 1877 merged with The Artist (L’Artiste, 1875–80), and especially the highly influential Young Belgium (La Jeune Belgique, 1881–97). Not only did these magazines publish essays on innovative French prose, but Zola himself was a regular contributor. What is more, since 1881 Wallonia had had a full-blooded representative of naturalism in the shape of Camille Lemonnier (1844–1913), characterized by a hostile Flemish critic as “Zola’s Belgian monkey.” Lemonnier’s literary followers referred to him more flatteringly as “the field-marshal of Belgian letters.” With the novel A Male (Un mâle, 1881), which deals with the love affair between a poacher and a farmer’s daughter and provoked controversy, Lemonnier introduced harsh, raw naturalism into Belgian letters. He went on to produce a number of naturalist novels, the best known of which is Ne’er-Do-Well (Happe-chair, 1886), about the wretched lot of workers in the steel industry.

Besides Lemonnier there were others, such as Georges Eekhoud (1854–1927). His Kees Doorik (1883) was set in a rural environment, which Eekhoud exchanged for the industrial docklands of Antwerp in his best-known novel, The New Carthage (La nouvelle Carthage, 1893). Lemonnier’s Ne’er-Do-Well, which depicts the survival of the fittest, may well have influenced the Flemish author Cyriel Buysse in his later novel Might Is Right (Het recht van den sterkste, 1893). However a direct connection is difficult to prove since both authors are indebted to Zola and his Germinal (1885).

Cyriel Buysse. Antwerp, AMVC House of Literature.

Initially, at least, the revival of French-language Belgian literature seemed to have little impact in conservative, agricultural Flanders, where the Catholic church played a key role. There are a number of reasons for the delay. In prose the idealizing tendency was still dominant, and art had been assigned a didactic function by clericals and liberals alike, its aim being to edify the backward Flemish people. The aversion to French and hence also to “French literary fashions” was a contributing factor. It deprived Flemings of the connection with Parisian culture that was so much easier for Belgium’s French-speakers. In addition Flemish cultural life was in the hands of schoolmasters and junior civil servants, for whom literature was a hobby and who could scarcely afford the leisure required for profound reflection. All this changed only very gradually as the end of the nineteenth century approached.

The Flemish public received their first taste of Zola’s work in their own language when a stage adaptation of L’Assommoir was produced with the emphatic title Drink!!! A Drama of the Common People in Nine Scenes (Drank!!! Volksdrama in negen tafereelen). The production was not reviewed by a single newspaper. Similarly, Zola’s individual novels received no critical attention. The appropriate response to the new fashion of dubious French origin seemed to be to ignore it. The most innocuous stories were torn to shreds if the reviewer detected even the slightest trace of Parisian degeneracy. “The [narrative under stricture] is a sample of the kind of work of which modern French literature produces a plethora, but which we sincerely wish to be spared,” wrote the critic Max Rooses — who, it is fair to add, revised his opinion after he had read Zola properly.

The first person to defend naturalism in a Flemish magazine was the Dutchman Frans Netscher. His article was one of the few indications that the mood was beginning to change. Gradually it became no longer possible simply to sweep Zola’s work under the carpet. Nevertheless, its influence was resisted tooth and nail, as something alien to the Flemish character. In 1888 a critic wrote: “Chasteness is the most splendid quality of our Flemish literature. Let us not rob it of that pearl. Let us never start rooting about on the dunghill of Zola and his ilk.” Another quote from the same period: “The Flemish novel, to its great credit, can in no way be compared with those rotten and pestilential growths that are today germinating and springing up in vast numbers on French soil. With us virtue and morality are the first prerequisite for the success of a writer of fiction.”

The first Flemish naturalist novel, Cyriel Buysse’s Might is Right (Het recht van de sterkste), did not appear until 1893, and it was a further two years before the more progressive periodical The Dutch Literary and Artistic Gallery (De Nederlandsche Dicht- en Kunsthalle) published the first full survey of Zola’s life and writings. This marks the end of the period of critical silence and mudslinging. Ironically, by that time Zola was regarded as passé in Paris, while in the Netherlands Van Deyssel, ever sensitive to the latest trends, had pronounced naturalism dead.

Cyriel Buysse (1859–1932) published his first naturalist novella, The Rush Weaver (De biezenstekker), in the Dutch magazine The New Guide in 1890; the mere fact that he published it in Holland says a great deal about the cultural situation in Flanders at the time. Three years later Buysse offered his novel Might is Right to the same magazine, but editor Willem Kloos felt that it contained too much of a sexual nature, which rendered it “unacceptable as a whole.” The magazine did, though, feature a prepublication, including a number of hard-hitting scenes that must have shocked contemporary readers.

In this first Flemish naturalist novel Buysse depicts the bleak life of Maria, a sensitive girl growing up in a rough slum populated mainly by poachers, drunks, and criminals. “For years she had cherished an ideal, a dream. Nature had fashioned her in startling contrast to her environment. Surrounded by thieves and villains, real scoundrels with appalling morals, she herself had remained honest and pure, the purer and more honest the lower the level to which she saw the others around her descending.” She wants to escape this pernicious environment and marry “a good honest fellow.” But this flower on the dunghill is cruelly snapped off. After visiting the fair, she is flung down in a cornfield like an animal and raped by the brutal Reus [Giant]. Reus asserts the right of might and she, as the weaker, must submit to his male strength. Although he subsequently tries, for a time at least, to mend his rough ways and treat her with more consideration, soon after their wedding he reverts to the merciless beast he was before. When he loses his job, he seeks out his old friends and resumes his criminal activities. Only when he is detained in prison for a while does Maria find some rest. After giving birth to her second child she falls gravely ill. Reus sexually assaults her sister before her eyes, and Maria finally dies a martyr’s death.

This heart-rending tale shocked readers with its realistic depiction of the lowest rungs of society. In a world of degenerates and criminals, Maria is seen as an unblemished exception. In portraying his heroine Buysse clearly gave in to his Romantic side, which comes to the fore particularly in his depiction of women — generally as the victims of brutal men. The figure of Maria is an idealistic remnant in the story, which, as Buysse himself indicated, was heavily influenced by Zola’s novels, especially Earth (La terre, 1887). What fascinated Buysse in Zola’s work was “the colossal movement of the masses.” The ability to create scenes involving a number of characters was also Buysse’s great strength as a storyteller. Like no other writer in Dutch he was able to depict the movement and turmoil of a wedding imploding, a poaching expedition, or a scene in a pub.

One of the most striking features of Buysse’s prose is the constantly recurring figure of the brute who acknowledges no law but the survival of the fittest. Time after time female figures longing for a better future fall victim to such bestial types. In his second great naturalist work, Jack of Spades (Schoppenboer, 1898), such an unreasoning individual is the book’s central character. Jan, the youngest of three unmarried farmer’s sons, is annoyed by the laziness of a cousin whom they have had to take into their home. His irritation mounts when this good-for-nothing marries a rich woman, who also comes to live with them. Dislike of his cousin and powerful desire for the beautiful Rosa unhinge the primitive mind of the young farmer, for whom possession of the girl would mean the ultimate revenge on his cousin. He tries no fewer than three times to rape her. When he at last succeeds, it proves fatal, as his cousin responds to the violation by murdering him.

Buysse tells this dramatic tale with a perfect sense of pace, and carefully records Jan’s moods as he is torn by hatred and desire. There are deceptive periods of calm, which lead the reader to think that the protagonist will be able to keep himself under control. The narrator only rarely distances himself from his characters, as in this passage, describing a fire on a farm: “And the people, not otherwise handsome, acquired, through this drama that affected them all so deeply, a picturesque and almost noble quality.” The passage comes at the beginning of the book; in the rest of the story the narrator is not a detached observer but writes from the perspective of the unruly main character. After Jack of Spades Buysse’s work changed. The intense, violent, Zola-like scenes were replaced by an ironic tone that softened the bleakness.

The pessimism in the work of Gustaaf Vermeersch (1877–1924) is all-pervading. He is one of those authors with a gloomy vision, whose life and work seem equally sad. A railway man who suffered from epilepsy — a disastrous combination of occupation and constitution — Vermeersch left a number of naturalist novels, of which his debut, The Burden (De last, 1904), is best known. The book’s cover shows a naked man struggling to carry a heavy cross. The content of The Burden makes it abundantly clear that the image represents the sexual desire that weighs on the main character. In a pub this shy young man plucks up the courage to speak to a girl, who despite other people’s warnings becomes his wife. The wedding degenerates into an orgy, in which the bridegroom sexually assaults his niece. It is an appropriate prelude to a thoroughly miserable marriage. At first the young couple live with the girl’s parents, a dreadful period for the protagonist, who again takes to drink. For a while he manages to resist the interference of his malevolent mother-in-law, but when, after an absence, she reappears, things go rapidly downhill. His wife neglects and abuses their child. When he is finally told that he is not the father, he drowns himself.

The following passage from the opening, where the protagonist reflects on his hopeless life after a bout of heavy drinking, sums up the book’s unrelenting grayness of mood:

He got up lazily, stretching repeatedly. Then he wandered aimlessly over the floorboards, flopped into his chair, and sat there at length without moving a muscle. He rubbed his forehead, which was pounding and full of stabbing pains, and his skull, which was burning hot. Slowly he began putting on his shoes, sometimes pausing to contemplate the thoughts that surfaced.

These were all gloomy and sad, the melancholy memories of lonely, bored wandering, with the occasional smudge of shame at humiliations he had undergone at hearing an unpleasant comment, at the sight of a hostile person. Immediately regret at the money he had frittered away welled up; he groped in his pocket and counted the ever-diminishing remainder. This was never accompanied by any satisfaction at pleasures he had enjoyed; they remained there in the twilight, where they could be just made out, though always in the distance. The aspirations and the longings never came to anything, and nor did any firm resolution. . . .

So his days passed in the silent town.

In a later work, Life on the Tracks (Het rollend leven, 1910), Vermeersch describes the wretched life of train guards, a life that he knew at first hand. His last novel was never completed, a fitting end to this naturalist life story.

Naturalism in North and South

There are striking differences in emphasis between naturalism in Flanders and in the Netherlands. In his great series of novels, Les Rougon-Macquart, Zola had juxtaposed two families, one, the Rougons, sanguine in temperament, the other, the Macquarts, of a more nervous disposition. Interestingly, the Flemish naturalists showed a preference for the sanguine types, violent and often rural, the Dutch for highly-strung individuals and refined city-dwellers. The differences are relative rather than absolute. For example, Buysse’s works also feature the kind of languid neurotic so well represented in the North. But in contrast Buysse’s great novels are full of larger-than-life primitive types, whose strength lies in their unrestrained passions. Northern novelists on the other hand liked to focus on unraveling weak, neurotic temperaments, while southern writers saw things in a broader social perspective. One could argue that Dutch naturalism was more psychologically oriented, while Flemish novelists painted a sociological panorama. In that respect the Flemish variant remained closer to Zola, who saw himself as something of an amateur sociologist.

Of course, the novelists were describing very different social strata. In Holland the upper and wealthy middle classes were scrutinized in novels that were virtually always set in towns — The Hague, Amsterdam, Rotterdam. Emants’s Juffrouw Lina, about a farming community, is an exception. Van Deyssel once moved to the country in order to write “a novel of the land,” but as usual he never got beyond the planning stage. Flemish naturalist literature almost invariably opted for the countryside as its setting, and indeed that was where the majority of Flemish speakers lived.

One thing that North and South have in common is that the element of social criticism, so prominent in Zola, is very muted. The novel rarely functions as an explicit social indictment. Interestingly, in both North and South social messages were more likely to be aired on the stage. Herman Heijermans’s play The Good Hope (Op hoop van zegen, 1900), an attack on the unscrupulous ship owners who pocketed fat insurance payments after the loss of their unseaworthy ships, and Buysse’s The Van Paemel Family (Het gezin Van Paemel, 1903), in which a family is torn apart by social divisions, both enjoyed huge popular success. Nevertheless, social activism is far less developed in Dutch-language naturalism than, for example, in its German counterpart.

A second parallel between North and South is the lack of response to Zola’s theories. In the North the scientific aspects of naturalism were questioned at an early date by the sharp-witted Van Deyssel. There are, admittedly, occasional traces of the theory of heredity, but the emphasis on the blind power of the genes often seems perfunctory and unconvincing. One novel, for instance, features a hunchback whose deformity stems from his father’s “somewhat debauched” sex life, while in another a girl in a dysfunctional lower-class family speaks upper-class Dutch due to the genetic influence of her father, a minor aristocrat she has never seen. In Flanders the scientific dimension was never very prominent, as Zola’s theories were largely ignored. It is symptomatic that in his later work Buysse played down the theory of heredity even further. In the second edition of Might is Right he scrapped a passage in which a criminal environment had been characterized as “degenerate.” One might ask, of course, what is left of naturalism without the theory? Would “realistic” not be a more accurate description for Buysse’s prose or the average Dutch naturalist? Though there is something to be said for this view, Zola remains the first great model. As Louis Couperus put it, Zola taught young writers “how to see Life as it was, without sentimentality, without romanticism, cruel and fatal.”

Whatever epithet one uses, there is one idiosyncrasy in the development of Dutch-language literature that distinguishes it from other literatures. The first stirrings of realism date from well before before 1885, but they are smothered by the conciliatory, idealizing context in which they invariably appear. In other words, literature in Dutch has almost no pre-naturalist realism. There was no Stendhal or Balzac, no Jane Austen or George Eliot. The realist novel emerged only after Zola’s sledgehammer had demolished the edifice of idealism. In that respect it is hard to overestimate his significance for the Low Countries.

One last question remains: why did naturalism persist for so long in Holland, in a watered-down form until 1930, while in Flanders it produced no more than a handful of novels? A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the fact that naturalism is scarcely compatible with a positive view of religion. This would explain why Buysse’s work, which showed little sympathy for the church, long met with such resistance in Flanders. By 1910 the naturalist impulse, which from the outset had been weak, had run its course there. The raw presentation of reality was replaced by a mythologizing or an idealizing depiction of country life in the work of Stijn Streuvels and Felix Timmermans respectively. Only around 1930, with the generation of Gerard Walschap, does realism make a strong comeback in the Flemish novel.

II. A New “Spiritual” Art, 1893–1916

Anne Marie Musschoot

Spiritual Art or the Rise of a New Mysticism

Albert Verwey and Willem Kloos had been the leading lights of The New Guide in its early days. However, Verwey left the journal’s editorial board as early as 1889 because of a personal rift with Kloos. Shortly afterward he also distanced himself from the hyper-individualism and aestheticism of the Generation of 1880 and went his own way. In 1894, with Lodewijk van Deyssel, he founded the Bi-Monthly Magazine (Tweemaandelijksch tijdschrift), which from 1902 onwards appeared as The Twentieth Century (De XXe eeuw). But it is mainly in the journal The Movement (De beweging, 1905–19), of which he remained the driving force throughout, that he corrected the course plotted by The New Guide. This gained Verwey a dominant position in Dutch literature that he was able to maintain into the 1920s.

Verwey took the view that the artist’s first task was not to express his individual emotions or record his sensual impressions. On the contrary, he should strive for an art that expresses an idea, a spiritual power that embraces the individual and the collective, that unites dream and reality and achieves a synthesis between artist and society. As mentioned in the previous section, Van Deyssel had prefigured this change of direction in 1891, when he described his own evolution from naturalism to mysticism in the essay “From Zola to Maeterlinck.”

The movement away from materialism and positivism was a phenomenon on a European scale. In the Netherlands there was talk of a “new mysticism” as early as 1900. A monograph on the subject called mysticism “the whole complex of approaches . . . used by our contemporaries to make contact with the world beyond the reach of our sensory perception.” This broad metaphysical orientation manifested itself in diverse forms, including theosophy, Buddhism, Neo-Platonism, spiritualism, occultism, magic, cabala, anthroposophism, and Satanism. Jules Huret’s Inquiry into Literary Trends (Enquête sur l’évolution littéraire, 1891), which showed that in France naturalism was on the wane and giving way to a whole variety of literary currents, was hailed by Dutch critics; the evolution observed by Huret corresponded with their own findings. The term “neo-mysticism” has since disappeared from literary histories, leaving only the designations “spiritual art” (or, in the case of Verwey, the “art of the idea”) and “symbolism,” while “neo-Romanticism” is used to designate a third variant of the same approach.

The Francophone Flemish author Maurice Maeterlinck, who was a passionate admirer of the fourteenth-century Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec as well as of Thomas à Kempis and Plotinus, played a major part in the spread of the fashion. Added to this there was the rapidly growing popularity of the dramas of the Norwegian Henrik Ibsen, in which critics identified mystical elements, while Leo Tolstoy, the prophetic advocate of a spiritual reawakening, also attracted a great deal of attention. Another telling indication is the great ceremony with which Sâr Peladan, the founder of the Rosicrucians and catalyst of the occult movement in France, was received on his visit to Holland in 1892. He made a particularly strong impact on a number of visual artists. In upper-class circles in The Hague people flocked to join the theosophical movement. Many of the ideas in a book like Madame Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine (1888), the bible of theosophy, found their way into in the work of Louis Couperus, including androgyny, spiritism, and various other occult phenomena. Frederik van Eeden, though a trained doctor, also experimented with spiritism.

Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949) was born in the Flemish city of Ghent but received his education in French, as did most of his upper-class contemporaries. He was in contact with the younger French symbolist poets, including Villiers de l’Isle Adam, and from 1895 he settled permanently in France. His early poetry, collected in Hothouses (Serres chaudes, 1889), is characterized by a decadent, oppressive atmosphere. However, it was his drama Princess Maleine (La princesse Maleine, also 1889) that marked his sudden breakthrough and quickly brought him international acclaim; in England he was heralded as “a new Shakespeare.” The poetical essay Wisdom and Destiny (La sagesse et la destinée, 1898) appeared simultaneously in Paris, London, and New York and was followed by a long series of influential philosophical treatises.