7: The Postwar Period, 1940–

I. From the Hunger Winter to the First Morning, 1940–1960

Ton Anbeek

Stone and Clouds

A young housepainter in a small provincial town in Flanders labors doggedly at his great novel. He has written more than four hundred pages and still there seems to be no end in sight. His wife, practical by nature, decides to intervene. She has read in the newspaper about a new prize for a book, a novel. So she sends her husband off to run some errands and takes advantage of his absence by writing at the bottom of the last full page, “And so on and so on.” She asks a girl in the neighborhood “who was learning to drum at a typewriter” to type out the text. Sure enough, the thick typescript wins the award. Louis Paul Boon (1912–79) receives the coveted literary prize for his debut, The Suburb Grows (De voorstad groeit). The book appears in print in 1943.

The factual truthfulness of the anecdote is less important than the story itself. At the very least it demonstrates Boon’s keenness to pass himself off as an “ordinary” writer, one who did not give a damn about literary pretensions of any kind. No muse, no divine inspiration, only a man who never stopped working. His book had been written at the kitchen table and completed by his wife, so it was she who should really be given the prize.

The Suburb Grows introduced a prose writer whose readers would be taken aback by the sheer epic force of his work. The reviewers voiced certain objections, of course, complaining that the structure was chaotic and the content excessively pessimistic. The accusation that he wallowed in misery would haunt Boon for the rest of his writing career, but the book signified a sharp break with prewar traditions. The composition was highly unusual. Unlike a traditional novel it features not one central protagonist but a series of characters, some of whom appear only briefly, while others are followed over a long period. If there is a central character in The Suburb Grows, it is the suburb itself. True, some earlier novels, notably those of Gerard Walschap, had featured a panoramic approach of this kind, but even in Walschap’s most famous novel, Houtekiet (1939), in which a village community figures large in the background, the main focus is on a single person or a small group of characters.

Boon himself pointed to John Dos Passos and Céline as sources of inspiration. It was probably Dos Passos who gave him the idea of using a kaleidoscopic perspective, such that the broad social canvas is more important than any in-depth psychological exploration of specific characters. The French author Céline reinforced Boon’s somber view of humanity. The Suburb Grows is a monument to pessimism, its message stark and clear: “Life is a wheel, and as it turns, the things you see are always new and always exactly the same.” Or, in another passage, “. . . have children, grow old, and die. Those who want a different life end up in prison or the madhouse.” There are quite a few people in The Suburb Grows who want a different life: artists with grandiose dreams, social reformers with high expectations; all are crushed by the same great wheel, which keeps on turning, regardless.

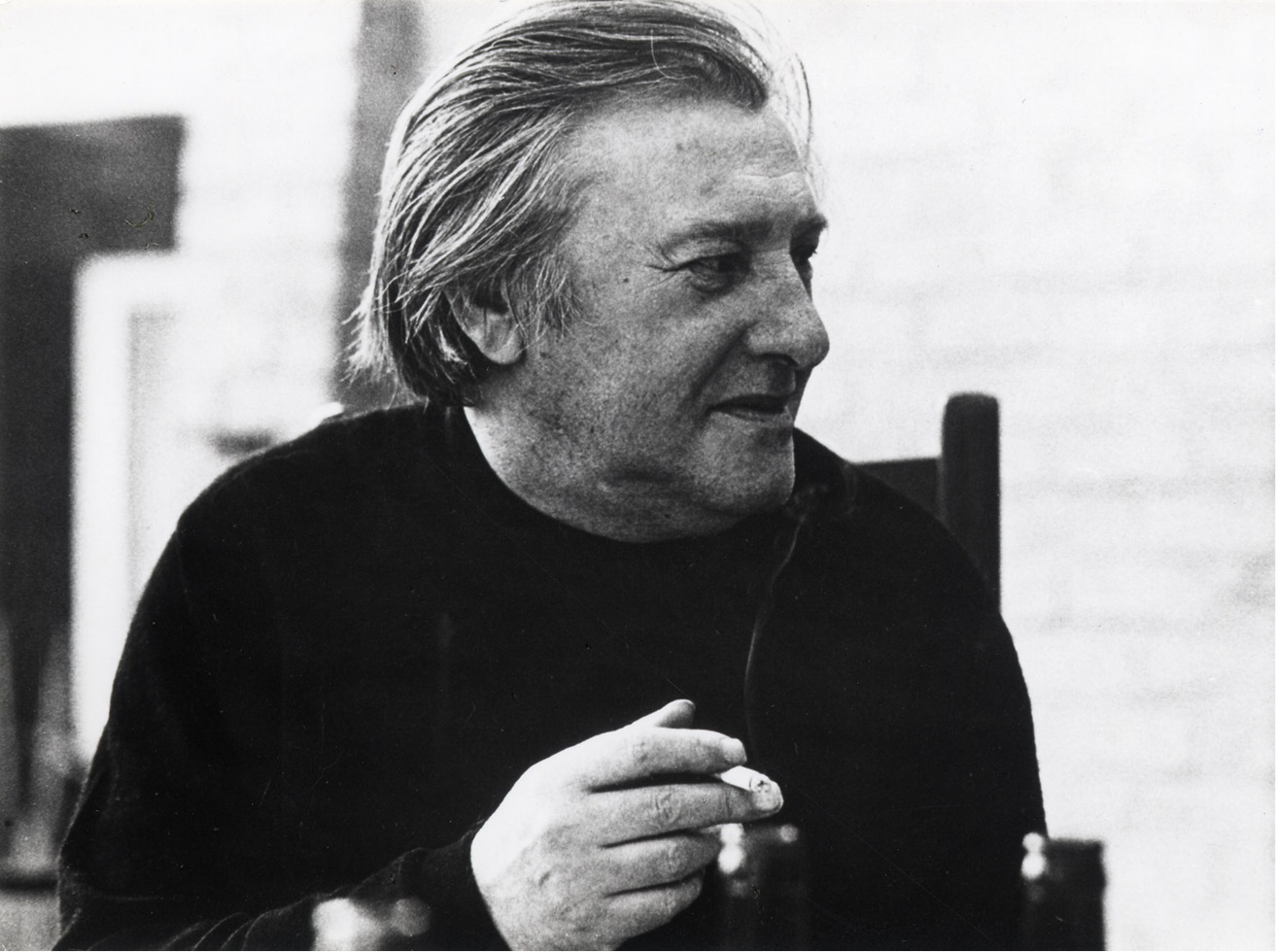

Louis Paul Boon, c. 1977. Antwerp: AMVC House of Literature.

Although Boon’s first novel holds out little hope of a better world, it does condemn the misery people inflict on each other. His entire oeuvre would address these two issues: although he remained deeply pessimistic, convinced things would never improve, he was also a moralist and a socialist, unable to resign himself to a situation in which a few had everything while most had nothing. In his third novel, Forgotten Street (Vergeten straat, 1944), he describes a curious experiment. Accidental circumstances cause a residential district to become completely cut off from the outside world. An anarchic community arises spontaneously, giving residents a brief illusion of freedom. But here, too, the ineradicable selfishness of humankind puts an end to the dream. As ever with Boon, greed and lechery operate as disruptive forces. Like The Suburb Grows, the book features a multitude of characters, presenting a panorama of human possibilities and, more especially, weaknesses.

Boon’s My Little War (Mijn kleine oorlog, 1947), a collection of anecdotes based on small newspaper items, is no less original. Taken as a whole, the stories reveal how ordinary people experienced the war, in particular life under occupation in small-town Flanders. Fear and hunger, collaboration serious or trivial versus quiet heroism, everything is seen through the eyes of a narrator who observes with astonishment how individuals behave in periods of extreme stress. The main character — Louis, or the author — does not make his presence felt to any great extent, although reading between the lines it is clear that his sympathies lie with the Communist resistance. This explains why the first edition of the book ended with the cry “Kick the people until they get a conscience.” The author added a new ending to later editions, closing the book with a sigh: “What’s the point of it all?” Boon the pessimist had defeated Boon the socialist.

In 1953 Boon published the book now regarded as his masterpiece, Chapel Road (De Kapellekensbaan). It took him ten years to write. A large and complex novel, it involves several interwoven storylines, including a historical strand in which he describes the rise of socialism. Boon chose to focus not on a socially committed leading figure (as he was later to do in Pieter Daens, 1971) but on a middle-class girl who looks down on socialist riffraff and prefers to associate with gentlemen of standing, who exploit and then abandon her. There is also a story with a contemporary setting, in which we encounter the author’s double, Boontje. He and his friends are forced to conclude that socialism has entered a sad decline; the old élan has been smothered by party discipline and cultural conservatism — the party opposes such modernist inventions as abstract art and “bourgeois” nihilist literature. The ex-Communist Boon has clearly been left with no illusions about a socialist utopia: What stance remains for a person refusing to conform to any party or doctrine? This dilemma is further explored in a third strand to the book, which tells the medieval story of Reynard the fox. Boon sees Reynard as a cunning non-conformist who curries favor with the upper classes in order to cheat them. Combative anarchism is the last resort of the vulnerable loner. Boon lays out this vision in a book that overwhelms the reader with its richness and multiplicity of voices.

Boon’s work breathed fresh life into Flemish — and, more broadly, Dutch — literature in different ways. First of all it introduced narrative techniques capable of evoking not just an individual life but the life of a community or an entire era. In this sense he expanded even further the broad vision of writers like Walschap. Second, he expressed, with devastating force, a deep social pessimism that had until then been merely a marginal presence in the Flemish novel. His fictional world negated the life-affirming attitudes in such prewar novels as Timmermans’s Pallieter and Walschap’s Houtekiet. Nor surprisingly, Boon’s nihilism met with a hostile response in the largely conservative Catholic Flanders and made him a hugely controversial figure. Finally, Boon’s work marked a decisive shift from the countryside to the city. His world is one of industrialization, exploitation, and social unrest. Just how much this setting differs from that of earlier Flemish prose becomes very clear when his work is compared with a novel published in 1952, a book that could be said to sum up all the major obsessions of the Flemish novel of the interwar years. Like Chapel Road, Wrestling with the Angel (Het gevecht met de engel) by Herman Teirlinck (1879–1967), by then the grand old man of Flemish letters, was a monumental work that presented a broad social and historical panorama.

Teirlinck’s novel pits two hostile groups against one another: the French-speaking aristocracy and the Dutch-speaking population. Theirs is an animosity all too familiar from prewar Flemish novels, but here Teirlinck seems to bring it to a head. He describes a Flemish family of more or less feral humans in a state of nature, a law unto themselves. In this sense they resemble Houtekiet. At the other extreme we meet the lord of the manor and his wife, specimens of degenerate nobility. Teirlinck neglects no opportunity to describe his ruling-class characters at their most decadent; the lady of the house, for example, indulges in sadomasochistic games with her maid. The narrator’s sympathies clearly lie with the uncivilized characters. A few years later Teirlinck would revisit the topic with a deft portrait of a decadent life in his novel The Man in the Mirror (Zelfportret of het galgemaal, 1955), in which an egocentric protagonist looks back on his cowardly life.

In Wrestling with the Angel the familiar contrast between blue-blood degeneracy and raw Flemish life-affirmation is taken to almost absurd extremes. In this sense the book provides a summary of fifty years of Heimat literature. By the time of its publication, however, the world around it had already moved on. Boon had published his urban novels and two years earlier, in 1950, a novel had appeared by a young man who was to play a unique role in Flemish literature: Hugo Claus (1929–2008).

The Duck Hunt (De Metsiers, 1950), Claus’s first book, has the traditional rural setting, but he certainly does not describe the Metsiers, the farming family at the center of the book, in traditional vitalist terms. They are an eccentric lot living quite literally at the margins of society. Their isolation is broken by the arrival, at the end of the war, of American soldiers, two of whom are billeted at the farm. In the ensuing tragedy, described with ingenuity and to great effect, nothing remains of the joyful religiosity professed by Timmermans before the war. The central characters want no truck with religion; the one son who does have faith is left alone with his doubts at the end of the book.

In a series of short chapters The Duck Hunt evokes the inner life of each character in turn, a technique borrowed from William Faulkner. The retarded Bennie is Claus’s version of Benjy in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929). Given that both Boon and Claus borrowed techniques from American literature, Dos Passos and Faulkner respectively, it could almost be said that the billeting of American soldiers at the Metsiers farm is symbolic of developments in the new Flemish prose in the wake of the Second World War. This does not mean that everything in Claus’s work is borrowed. The presumption of influence is always a matter of recognition and attribution. The figure of Bennie, for example, the retarded boy in The Duck Hunt who represents a purity lost by the adults who have adjusted to the realities of life, returns time and again in Claus’s work.

In his second novel, The Dog Days (De hondsdagen, 1952), purity is embodied in the young girl Bea, the subject of the protagonist’s quest. As soon as she begins to behave too much like an adult he leaves her, thereby saying goodbye to his own youth. It is no accident that she is called Bea; Claus repeatedly alludes to Dante and his Beatrice. In this novel he introduces something that will become a constant in his work: a perpetual intertextual game with older literary sources, including Greek myths and, in a more general sense, the vegetation myths described by J. G. Frazer in his study The Golden Bough (1890–1915). Another important influence emerged in The Dog Days, that of existentialism. It declares itself in sentences like, “Who will ever hear this game, this game of goose, that I regard as a game but that others, those lumps of meat on two legs who surround me and whom I mimic and apparently have to mimic in order to exist, will regard as a tragic dilemma?” On another page the “lumps of meat on two legs” are described as the “collections of arteries, nerves, small bellies, small heads, that become big bellies, big heads and each in their own time split open and eventually stick together.”

In the prose of the period such passages abound. The 1950s were not a cheerful time in Flemish literature — or indeed in Dutch literature more generally, as we shall see. Take for example the first novel by Ward Ruyslinck (1929–), The Depraved Sleepers (De ontaarde slapers, 1957), in which a married couple live out their lives in total apathy. The husband, a pathological liar, uses every possible means to avoid work. The wife, traumatized by the war, expects military conflict to erupt again at any moment. When she sees signs that it has begun, with her husband apparently the first victim, she commits suicide. This depressing story is told in sober, lucid prose.

The same is true of The White Wall (De witte muur) by Maurice D’haese (1919–81), which also appeared in 1957. It deals with the confessions of a murderer, written in his cell. Again we encounter a protagonist who simply lets life wash over him, and once more a shocking picture of human existence emerges. The style fits the character’s somber vision: “The gray, sick morning crept slowly and thickly over the roofs and slid like a cold, slimy reptile in through the window, until the sun stood big and hateful on the red, gleaming skyline of the woods.” At the end of the confession we learn that the main character has shot a man dead, “just like that.” The fact that the victim is of North African origin brings the book even closer to its model, The Outsider (L’étranger, 1942) by Albert Camus, in which the anti-hero commits a murder “because of the sun.”

D’haese’s novel reads like an existentialist catechism, at least for existentialism’s early, non-political, phase. While the plot derives from Camus, the viscous style is reminiscent of Jean-Paul Sartre. Contemporary French literature had a profound effect on the young Flemish writers of the immediate postwar era. Sartre and Camus showed them a world they recognized all too well, a world both pointless and disgusting. In an author with such a rich imagination as Claus this was a passing phase, and the same can be said of Ruyslinck, whose many subsequent books would focus on the lonely struggle of the individual against the collective. Nevertheless, the novels of the 1950s display a surprising similarity of theme. In an absurd world, people appear as “lumps of meat” (Claus) or “filthy, useless animals” (D’haese); life is “a book of which one would read the first chapter attentively before slamming it shut, knowing what would happen in subsequent chapters, knowing that all books were like this” (D’haese). For that matter, this last description could apply to all these novels of the absurd.

The most original work of this type is a novel by Jan Walravens (1920–65) with the characteristic title Negative (Negatief, 1958). Again it is a novel in which all kinds of awful things happen, and the protagonist is a marginal figure, in this case a kleptomaniac who has committed two murders as well as several other abhorrent acts, such as giving a child a razor blade to play with. His unhappy childhood — he was beaten by his parents, moved between children’s homes, and so on — is supposed to explain his extreme malevolence. The book’s originality lies in the way the unsavory anti-hero is confronted with an unexpected insight at the end, when his opposite number asks: Does not the negative always assume the positive? “And how could that shadow exist unless there was an object that, within light, casts a shadow? That object, the sun, the positive, is present everywhere, is presumed anywhere where there is a shadow, a darkness, or a negation.” The main character has no defense against this intelligent argument; in fact he feels defeated, although he clings to the idea that “A failure like mine is almost a success.” Negative employs all the clichés of the period but ultimately turns them on their heads. Walravens had the talent to grow into a major novelist, but he died young; he was one of the key figures of postwar Flemish literature, and later in this chapter we will look at his role in defending the new poetry.

Each of these writers illustrates the extent to which prose emerging after the Second World War differs from that of the interwar period. There are no longer any life-sized characters like Houtekiet. Instead, grubby marginal figures observe a human society in which they no longer wish to participate. Vitality has been replaced by revulsion.

Ivo Michiels (1923–) is a novelist who, like Claus, passed through an existentialist phase before going on to carve out a path of his own. His development is typical of many young Flemish writers of the time. Once a good Catholic and a conservative reviewer, he became a prophet of the new take on life. The experience of war had destroyed his old ideals, as he describes with great clarity in his early coming-of-age novel, The Crusade of the Young (Kruistocht der jongelingen, 1951). His first major work of fiction, The Parting (Het afscheid, 1957), echoes several other existentialist books of the 1950s. The main character finds himself in a situation fully deserving of the epithet absurd. Every morning he has to report to a ship about to leave on a secret mission, but his departure date keeps being postponed. Time and again he has to say goodbye to his family as if setting out on a long journey. His past, dominated by war and death, is sketched in flashbacks. The book’s atmosphere is heavy with fear and uncertainty. The only person who manages to maintain some dignity in these distressing circumstances is the protagonist’s wife. She represents a positive factor, if a very small one, in an otherwise relentlessly existentialist novel.

The Parting contains various stylistically interesting passages that foreshadow the author’s later work. Michiels was to emerge as an experimental prose writer without equal, as demonstrated by his next novel, Book Alpha (Het boek alfa, 1963). This work marks the start of a period in which experimentalism would flourish throughout Flemish prose. For this reason alone, Book Alpha deserves to be assigned a key position in the history of Flemish literature. This is not to say there was no experimentation before 1963. Boon’s Chapel Road, with its ingeniously interwoven storylines, was certainly no traditional novel, and the same goes for Claus’s The Dog Days, with its clever alternation between past and present. But at the very least Michiels reinforced and redirected a tendency to experiment with the novel as a form.

Despair, disgust, the shattering of the ego — in many West European literatures the Second World War seems to have left a desolate scene. Interestingly, there was also a countermovement in Flemish prose in the magic realism of Johan Daisne (1912–78) and Hubert Lampo (1920–2006). Daisne published his first novel, The Staircase of Stone and Clouds (De trap van steen en wolken), in 1942, long before the war ended. The title is programmatic: life consists not only of hard reality (stone) but equally of imagination and dreams (clouds). Two stories, one quasi-realistic, the other more like a fantasy, are interwoven to such an extent that ultimately the reader cannot tell what is “real” and what is not. Many years later the novel would be recognized as an early example of postmodernism; Daisne himself used the term “magical realism,” a symbiosis of dream and reality.

He gave convincing form to his artistic creed in The Train of Inertia (De trein der traagheid, 1950). A man sitting in a train on his way home finds himself, after an unscheduled stop, in the borderland between life and death along with several fellow passengers. At an inn, where an unfamiliar language is spoken, he encounters a beautiful, enigmatic woman. Each of his fellow travelers “recognizes” her in a different way. Eventually the main character wakes up in hospital: he seems to have survived a train crash. Daisne elaborates upon this strange fact with great lucidity and in the process his narrator clearly defines his beliefs: “In my own way, . . . I clung then, as I do now, to life, to the delightful significance of this reality.” The phrase “the delightful significance of this reality” is unique in a period dominated by the existentialist prose of despair and disgust. The magic realist embraces life, because for him it consists not merely of raw reality but just as much of magic and mystery.

In the most famous novel by Daisne’s fellow magical realist Hubert Lampo, The Coming of Joachim Stiller (De komst van Joachim Stiller, 1960), the protagonist receives a letter from the past. The atmosphere is filled with a sense of apocalypse. His contact with the sender of the letter, a certain Joachim Stiller, intensifies, and it seems they will finally meet, but at the crucial moment Stiller is run over: he lies in the road as if crucified. The Christian symbolism is reinforced three days later when the body has apparently vanished. The book explores the interference of the supernatural in earthly affairs, a phenomenon both frightening and comforting. Lampo further developed his theory of magical realism in later years, drawing on Carl Jung. His novels were appreciated by a wide range of readers, who clearly valued Lampo’s worldview more highly than the depressive prose of the existentialists. Lampo chose a traditional form for his novels, making them a good deal more accessible, in spite of their magical elements, than the work of experimental writers like Ivo Michiels. Literary criticism became increasingly hostile to magical realism and dismissed it as cheap hocus pocus, but readers remained loyal to Lampo for many years.

Lessons of the Hunger Winter

Our survey of modern Flemish prose began with Boon’s novel The Suburb Grows, published in 1943. People in Holland often find its year of publication surprising. How could a novel with such a pessimistic tenor, a book so diametrically opposed to Nazi propaganda in all its forms, have been published in the middle of the war, in a country living under occupation?

The riddle is easily solved. Occupied Belgium was run by a military regime, which left room for a degree of cultural freedom. In the Netherlands the Nazis established an ideologically motivated civilian government that tried from the outset to reform Dutch society in a spirit of National Socialism. As early as August 1940 it was announced that no printed texts could be distributed without the prior approval of the occupying regime. By the end of the year libraries were forbidden to lend out books with anti-German content. Most important of all was the establishment in November 1941 of the so-called Chamber of Culture (Kultuurkamer). Anyone who declined to join the Kultuurkamer was banned from exhibiting art or publishing literary work. In other words, after 1941 normal cultural activity became impossible. Anyone unwilling to comply with Nazi demands and who wanted to publish had to do so clandestinely. In the Netherlands a book like The Suburb Grows could never have been published during the war, let alone have won a prize.

There were other differences, too, between Dutch and Belgian wartime circumstances. The German invasion of May 1940 had come as a greater shock to the Dutch than to those Europeans, including the Belgians, who had been affected by the First World War. Many Dutch people believed, or hoped, that their country would be able to maintain its neutrality in the current conflict as it had in the last. This attitude, now considered naive, is quite understandable. The Netherlands had seen no enemy troops on its native soil since the days of Napoleon. Apart from some minor unrest over the border in Belgium around 1830 and various colonial conflicts, the country had been spared any kind of military confrontation. This period of tranquil detachment came to an abrupt end on 10 May 1940. The experience of occupation was completely new to the Dutch, in contrast to the Belgians who had seen their country turned into a European battlefield by foreign powers in 1914–18.

Another factor was that the Second World War lasted longer in the Netherlands, across most of its territory, than in Belgium. By the autumn of 1944, Belgium and the southern part of the Netherlands had been liberated, but after the Allies lost the Battle of Arnhem in September of that year, the region of the Netherlands north of the Rhine remained under German occupation for another nine months. The winter of 1944–45 was particularly harsh and brought terrible suffering to the urban population. A lack of food and fuel forced city dwellers out into the countryside to exchange any valuables they had for potatoes. Death by malnutrition was widespread; exhaustion and cold finished off those weakened by starvation. The state of utter desolation brought about by what became known as the “hunger winter” was to make a profound impression on the young writers who would shape Dutch literature after the war.

When the country was finally liberated in its entirety in May 1945, every effort was needed to enable normal life to resume. The few voices calling for radical political and economic reform elicited little response. Straitened circumstances did not encourage revolutionary change. In political terms the country that rose again after 1945 was almost identical to that of the prewar years; the separate ideological currents or “pillars” that dominated political and social life were exactly like those prior to 1940. It seems that distressing living conditions drove individuals to seek support within their own ideological pillar.

At first the literary life of the nation presented a rather similar picture. Despite calls for “renewal” there were no serious attempts to define what the new literature should look like. At most there was agreement on the importance of an author’s “personality,” on the rejection of purely aesthetic art and the glorification of form in favor of social commitment, and on the need for a broadly international outlook. All these requirements clearly reflected the program of the prewar Forum writers.

Shortly after the liberation, therefore, Dutch literature found itself in a paradoxical situation. In theory there was plenty of room for reform and renewal. After all, three of the leading literary figures of the interwar years had not survived May 1940: Hendrik Marsman had drowned, Edgar du Perron had died of a heart attack, and Menno ter Braak had committed suicide. Dutch literature had been decapitated, but as a result writers turned more than ever to the work of Ter Braak and Du Perron, authors who had vigorously opposed the Nazis. The Forum duo of Ter Braak and Du Perron overshadowed literary production in the early postwar years. Only very gradually did a handful of writers manage to wrestle free of their influence.

It would be wrong to conclude that these years were devoid of significant novels. In 1948 an author of the older generation, Simon Vestdijk, published Pastorale 1943, which paints a sobering picture of a resistance group in rural Holland. Three times they try to kill a pharmacist suspected of treachery. The failure of the first two attempts is described in comical detail, yet the most disturbing aspect is that the pharmacist is innocent of the crime for which he is eventually killed, as the reader is aware early on.

Vestdijk appears to have precious little respect for the resistance. Here is the protagonist thinking about a fellow resistance fighter: “He even asked himself whether, if the little man had been born in Germany, or in the Netherlands under different circumstances, he might not have become an extremely useful member of the Nazi party, aggressive, vain, and intolerable as he was.” Being on the right or wrong side, it appears, is largely a matter of accidental circumstances. This attitude was highly unusual in the early postwar years, when a myth was being created of a nation that had resisted the Nazi occupation practically to a man. The image was reassuring, particularly for those who had cooperated to a greater or lesser extent with the Nazis — in other words practically the entire population. Not until the late 1990s did the Dutch acknowledge that only a tiny number of people had been active in the resistance. An equally small number had actively collaborated, out of personal conviction or for profit, while the large majority had accommodated the Nazi regime in one way or another. Remarkably, this unblinkered view of life under occupation is reflected in literature at a very early stage, not only in Vestdijk but also, for instance, in Willem Frederik Hermans (about whom more later), and in a book like Louis Paul Boon’s My Little War.

Pastorale 1943, published in 1948, was not reissued until 1966. Its publishing history is symptomatic of waning interest in the Second World War. Bookshops were selling off war books at half price, so publishers felt little inclination to put more on the market. Several factors may account for this repression of the collective memory of the war. Attempts to bring collaborators to justice had ended in a fiasco: too many had been arrested and locked up in camps on the basis of spurious allegations; the camps were run in ways which, to everyone’s dismay, strongly resembled those of the Nazis; and those who had profited most from collaboration, the contractors and industrialists, seemed to escape retribution. So many other pressing problems needed to be solved. The threat of a third world war, this time with atomic weapons, held the western world in a state of fear. Amid all this the Dutch had to face an additional catastrophe: after a bitter struggle their rich colonial possession, the Dutch East Indies, gained independence in 1949 and would henceforth be known as Indonesia. Many in Holland believed that the loss of the colony would mean lasting poverty. All these worries distracted attention from the past misery of the Nazi occupation.

It is telling that the most important novel to appear in these early postwar years, The Evenings (De avonden, 1947), barely mentions the war at all, even though the story takes place in December 1946. Written by G. K. van het Reve (1923–2006), who later shortened his name to Gerard Reve, it is a prime example of the literature of suppression. The story concerns the monotonous existence of a young office clerk still living at home with his parents. He spends his evenings with friends, indulging in cynical conversations: “‘Mind you, things like that enrich life,’ said Jaap. ‘The sick and malformed. If I see a wooden leg or an old woman using a stick with a rubber tip, or a humpback, it makes my day.’” It would be hard to think of a greater contrast than that between this novel and a book like Edgar du Perron’s Country of Origin (1935), in which intellectuals engage in sophisticated discussions of art, politics, and morality. The characters in The Evenings talk about baldness, disease, bodies, and funerals. Reve reduces the human being to its imperfect body.

Gerard Reve. Photograph: Eddy Posthuma de Boer.

The Evenings is certainly not a cheerful book, although its accumulation and repetition of trivialities sometimes has a comic effect. The fact that the story takes place in the last ten days of the year makes the atmosphere all the more dispiriting. The protagonist has several days off work, which only adds to the grayness and boredom. What shocked reviewers most of all was not so much what Reve described as what he omitted; indeed, the book is devoid of any higher values or ideals. Nearly all the critics connected this attitude with the war. The jury that selected The Evenings for an award stated in its report, “This is not just any old history of a human soul but a book that demonstrates what the times, which have destroyed all illusions, have done to today’s youth.” The central character was widely regarded as representing young people uprooted by the war. The Evenings became a milestone in the history of postwar Dutch prose. It meant a radical break with the heritage of Forum and a general assault on prewar intellectualism. In his debut Reve had set a tone that would dominate prose until at least 1960; from this point on, novels would feature disillusioned characters mumbling acid comments on their depressing environment.

Although some years older, Anna Blaman (1905–60) was regarded as belonging to this new group of writers known as the disillusioned realists. With her novel Solitary Adventure (Eenzaam avontuur, 1948) she shocked readers by daring to write openly about homosexuality, a subject that was still more or less taboo in the Netherlands. Reproached for presenting characters driven purely by unrestrained lust, she was referred to as a writer “who dragged love down.” In Solitary Adventure love is called “disguised loneliness,” a definition immediately followed by another unambiguous thought in the same vein: “Love, happiness, they seemed indeed like the brief incubation period of a terrible sickness, a sickness of the soul that leaves sufferers somber and grim, and hostile, and deranged.” Readers of the period could be forgiven for failing to see that Blaman’s message was far more subtle than these statements suggests.

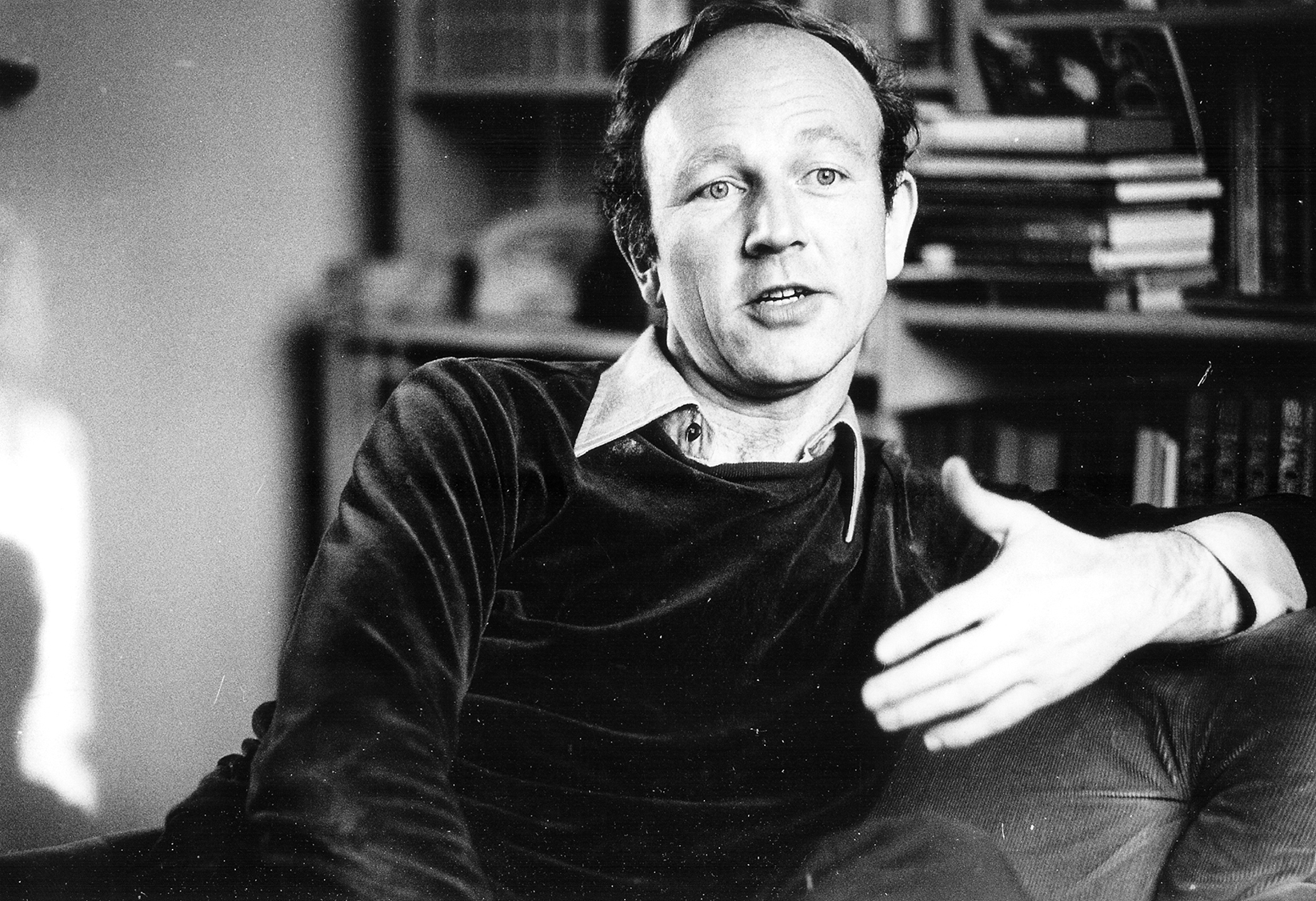

W. F. Hermans in Groningen. Amsterdam, Maria Austria Institute, Photograph: Wim van der Linden.

The author who provoked most hostility at this time was undoubtedly the young Willem Frederik Hermans (1921–95). The war had been Hermans’s main formative influence. In May 1940 he faced a personal tragedy: his elder sister committed suicide along with her married lover. The episode shattered the apparent orderliness of bourgeois life. Chaos revealed itself, a chaos hidden in peacetime by convention and hypocrisy. The “hunger winter” completed Hermans’s education.

When that war ended, I was twenty-three. Well, I’d certainly been given a very peculiar view of the human spirit by that time, one that has never left me. . . . I mean, in a war like that you can’t walk around with a piece of dry bread in your pocket without having to keep both hands on it. Otherwise they’ll rip it off you! It’s amazing to see the criminal acts supposedly respectable people are capable of in a desperate situation like that.67

Hermans had difficulty finding a publisher for The Tears of the Acacias (De tranen der acacia’s). Chapters that had appeared in literary magazines were regarded as so offensive that at first no publisher was prepared to take the book on. It was not brought out until 1949, and reactions were indeed fierce. Readers objected to several overtly sexual passages and were no less upset by the way the resistance was portrayed — in Hermans’s view it seemed to have consisted mainly of braggarts and fantasists. His picture of life in occupied Amsterdam was as grim as it was shocking. For the protagonist the liberation is barely a salvation from tyranny at all; as he walks through a jubilant Amsterdam he makes some telling comparisons:

Outside there were brief bursts of sunshine. His mouth tightened with bitterness. Never, never would the misery end. Everything was as it had been. When something you had long expected finally happened, it was so colorless and tasteless that it seemed as if you had never dreamed of it for a second. One mess or another mess, it all came down to the same thing. The flags swirled before his eyes. It was as if the houses were hanging out their intestines, as if the city had finally gone mad. These colored woolen fabrics did not belong in the outdoor air. Nevertheless he looked at each flag in turn; not one of them was hanging straight; they twisted around their poles as if ashamed to fly for such a victory.

At the time readers saw The Tears of the Acacias primarily as a disillusioned novel about wartime life, with a cynical protagonist as the author’s mouthpiece. They failed to notice that Hermans’s ambitions went beyond mere demystification, since they took it for granted that a young author would write an angry book. Later commentators observed that Hermans was already addressing what would remain the key concern of his oeuvre: the world cannot be known. The central figure in The Tears of the Acacias is obsessed by the fact that he keeps hearing contradictory verdicts on the people around him. Is his best friend a hero or a “lousy traitor”? Is his sister working for the resistance or is she simply a “kraut-whore”? It seems impossible for him to discover the truth, which leads to bewildering uncertainty about his own identity. This problem dominated Hermans’s early work. The wartime background provided fertile territory, because in a country under occupation the ability to ascertain what others are thinking may be a matter of life and death.

Contemporary readers overlooked such philosophical issues in the book, seeing it above all as an outpouring of what an older critic called “the life lessons of the hunger winter.” Another reviewer described the prose of Blaman, Hermans, and Van het Reve as “the cynical and sullen tarnishing of the beautiful things in life.” This type of prose constitutes the Dutch equivalent of existentialism, which was in vogue across western Europe after the war and found its most notable expression in France. The Dutch authors, however, were not writing under direct French influence. Hermans, for instance, had formed his view of the world before familiarizing himself to any significant extent with French existentialism; his early work is closer to surrealism. Blaman’s novel Woman and Friend (Vrouw en vriend) was published in 1941 and thus predated the influence of existentialism, although she was a teacher of French and went on to develop a detailed knowledge of French existentialist literature, which left obvious traces in her later prose. One aspect of French existentialism found no parallel in Dutch literature: the emphasis on human solidarity in the later work of Sartre and Camus.

In its own day this “prose of disillusionment” drew attention mainly from critics who were scandalized by it or worried about its effect on the public. Of course, there were novels and stories that did not fit the mold created by Blaman, Hermans, and Van het Reve. One example is the work of Maria Dermoût (1888–1962), who spent most of her life in the Dutch East Indies and then Indonesia. Her prose has a highly individual tone, as she seeks to ally herself with an oral tradition that involves magical and fairy-tale elements. Her work stands in clear contrast to the harsh realism of writers in Holland, which is not to say she is all sweetness and light. In her novel The Ten Thousand Things (De tienduizend dingen, 1956) the Indonesian archipelago is evoked as a place where the boundaries between reality and myth, between past and present, and between the living and the dead dissolve. It does not seem the slightest bit odd that a man and a boy are described as “being really a shark and a little shark.” Dermoût’s work found a large readership, and not only in the Netherlands: it was received with enthusiasm in America as well. A. Alberts (1911–95), who achieved recognition in 1953 with the collection of stories The Islands (De eilanden), was also inspired by his experiences in the colonies.

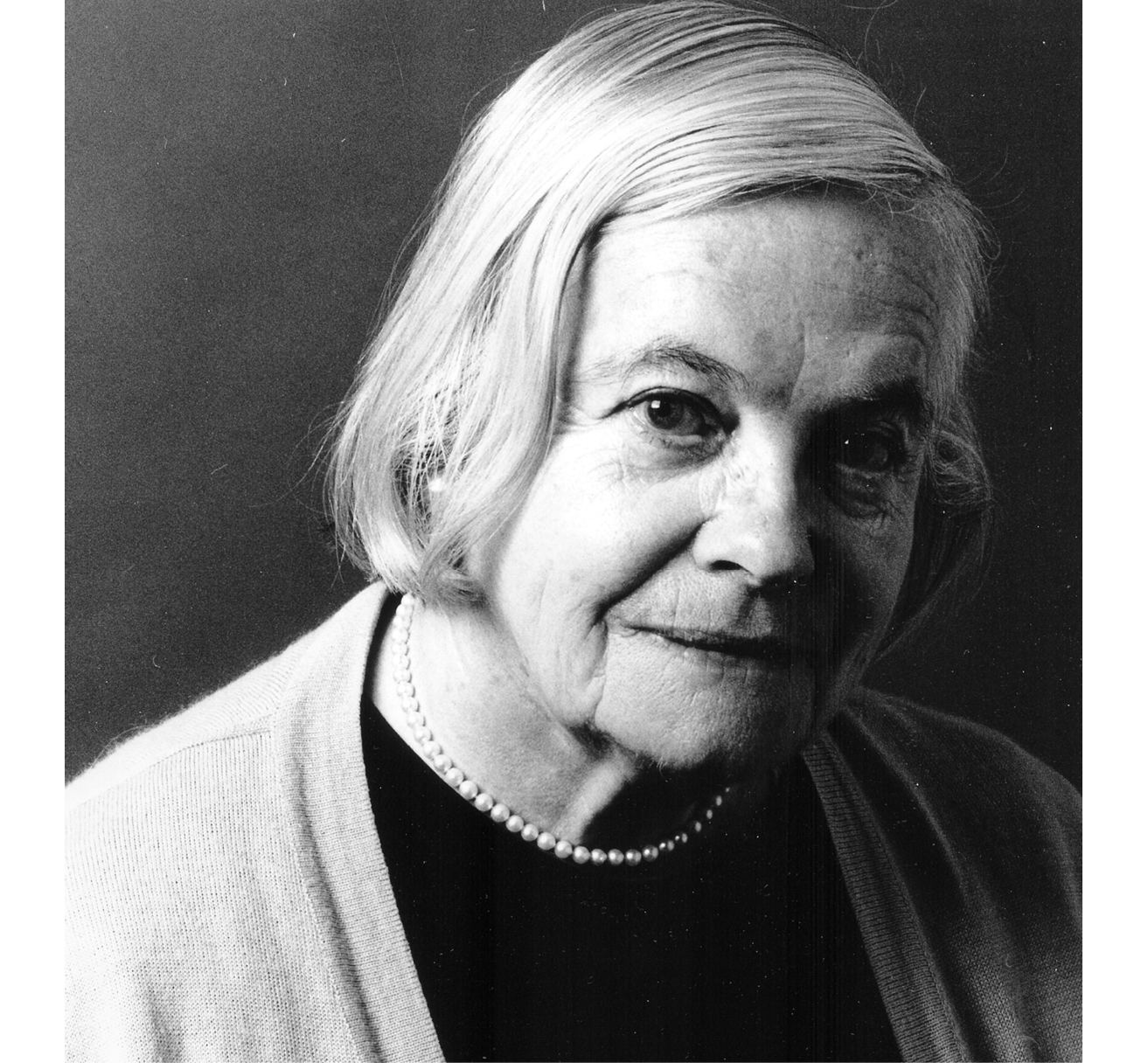

Maria Dermoût. The Hague, Literary Museum.

In the 1950s there were signs of a return to the Second World War as subject matter. The history of the diary of Anne Frank (1929–45) reflects this. Anne’s father, the only member of the family to survive the concentration camps, tried to interest various Dutch publishing houses in the text immediately after the liberation, but it was only when a highly respected historian gave his support that the diary found a publisher, appearing under the title The Annex (Het achterhuis) in 1947. Not until the latter half of the 1950s did the book begin to win the international fame that still brings thousands of tourists each year to the house on the Prinsengracht in Amsterdam where the Frank family lived in hiding. Until quite recently The Annex (later English editions were entitled The Diary of a Young Girl) was the only modern Dutch book known to readers abroad. There are several different versions of the text. In the first edition, passages about sexuality or that include criticism of Anne’s mother were omitted. In fact, Anne herself had already edited her diary. An authoritative scholarly edition appeared in 1986 partly as a rebuttal to Holocaust deniers who cast doubt on its authenticity; it has since been further expanded.

The main significance of The Annex was, and still is, that the book gives a face to the abstract figure of six million Jews killed by the Nazis. Anne’s lively style evokes the stifling atmosphere of the hiding place yet also shows how she managed to retain her humor and inventiveness in confined circumstances. At the same time we follow her development from a child into a young woman. In this context it is useful to look at another witness to the Holocaust. In her short novel Bitter Herbs (Het bittere kruid, 1957), Marga Minco (1920–) evokes the war through the eyes of a Jewish child and includes a number of disguised autobiographical elements. Her story is all the more gripping because she employs a sober, almost businesslike style in her descriptions of horrific events.

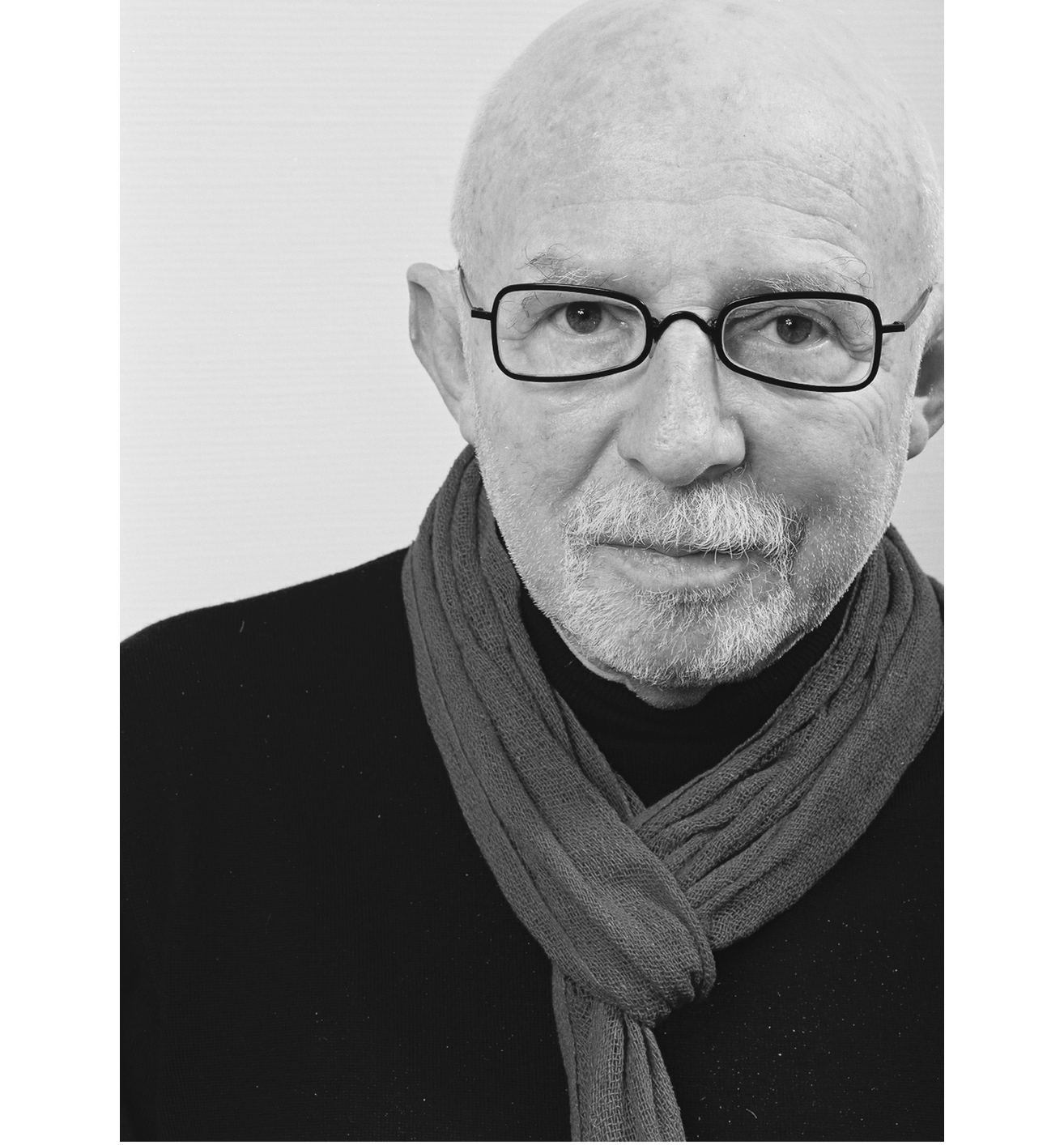

Marga Minco. The Hague, Literary Museum.

In the late 1950s two novels appeared that are among the greatest achievements of postwar Dutch literature and were immediately recognized as such by literary critics: The Darkroom of Damocles (De donkere kamer van Damocles, 1958) by W. F. Hermans and a year later The Stone Bridal Bed (Het stenen bruidsbed, 1959) by Harry Mulisch (1927–). The publication dates are significant: internationally, several novels now recognized as literary classics about the war appeared around the same time, including The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel, 1959) by Günther Grass, The Last of the Just (Le dernier des justes, 1959) by André Schwarz-Bart, and Catch 22 (1961) by Joseph Heller. It seems that quite some years have to pass before profoundly affecting experiences like those of war can be portrayed convincingly.

W. F. Hermans’s The Darkroom of Damocles can be read on several different levels. First of all it is an absorbing war story about a character called Henri Osewoudt, who becomes involved with the resistance and liquidates several collaborators on the orders of one Dorbeck. The plot resembles that of an ingenious thriller, the major difference being that the reader’s most urgent question remains unanswered: does Dorbeck, the man who has been issuing orders to Osewoudt, including orders to kill, really exist? Did he ever exist? Or is he is a product of Osewoudt’s imagination? The second level is psychological, concentrating primarily on Osewoudt’s personality. His biological inheritance is unfortunate: his mother suffered from delusions and he is cursed with an inability to grow a beard. Have these afflictions led him to dream up his own virile doppelgänger? The book also works at a philosophical level, illustrating the thesis that humanity and the world cannot really be known. This reading is supported by a quotation from Ludwig Wittgenstein that Hermans added to the text from the tenth edition onward.

If ultimately The Darkroom of Damocles centers on the impossibility of gaining certain knowledge about the world, there is another aspect that some contemporary critics rightly pointed out: the novel’s anti-moralistic, nihilistic tenor. Imprisoned as a collaborator after the liberation, Osewoudt meets a young man who calls himself a “great amoral theorist,” who joined the SS when Germany was already losing the war even though he was not particularly interested in Nazi ideology. He developed a worldview of his own:

But what I do believe is that moral values are nothing but a temporary frame of reference, and that once you’re dead morality is irrelevant. . . . But to anyone who accepts the reality of death there is no morality in the absolute sense, to anyone like that goodness and charity are nothing but fear in disguise.68

The statement is made by a fictional character, so it cannot simply be attributed to Hermans, but no one in the novel contradicts its tenor. True, it is counterbalanced by the opinions of Osewoudt’s uncle, a man with a philosophical bent, but he is presented as a half-baked and rather unworldly idealist. The events of The Darkroom of Damocles tend to bear out the amoralist’s views rather than those of Osewoudt’s Hegel-quoting uncle.

Hermans’s “amoral theoretician” has much in common with the main character of Mulisch’s novel The Stone Bridal Bed. Here too we find explicit distrust of morality and civilization; culture is merely a mask for the barbarity that underlies it, the ultimate chaos. Both Hermans and Mulish had developed a jaundiced view of humanity as a result of wartime conditions, and both would revisit the subject of the Second World War time and again to illustrate their ideas. While for Hermans the unknowable nature of the world becomes undeniably clear in the diffuse circumstances of occupation, Mulisch focuses more on elements like time and history, with the question of guilt as a recurring theme. Both authors, who along with Gerard Reve are regarded as the most important of postwar Dutch prose writers, were molded by the experience of war, as their work testifies. In these years the message is far from cheerful.

Simon Vestdijk. The Hague, Literary Museum.

The focus on young writers of disillusioned prose should not obscure the fact that older authors were producing some of their best work. In The Waiter and the Living (De kellner en de levenden, 1949), for example, Simon Vestdijk responded to existentialist questions about life. Twelve residents of an apartment building are rounded up to participate in proceedings of a remarkable kind. They represent the stakes in a bet between Christ and God the Father: when hard times arrive, will humanity curse God and its own existence? In this apocalyptic atmosphere, a kind of mock Last Judgement, the devil does his best to win over the twelve characters with inducements and threats, yet ultimately he fails. The novel contains no explicit references to the war, but events mirror those of Hermans’s novels, putting people in extreme situations to test the constancy of their values. Comparisons with The Plague (La peste, 1947) by Albert Camus are pertinent, since both Camus and Vestdijk address existential values. But in contrast with the disillusioned realism that was spreading inexorably at the time, Vestdijk’s novel concludes with an overt acceptance of life: Christ wins the bet with his Father, because humanity cannot bring itself to curse God.

In the late 1950s an interesting development took place in Vestdijk’s writing. In 1956 he published The Glittering Armor (Het glinsterend pantser), ostensibly a novel about friendship. Novelist S. tells the reader about his childhood friend Victor Slingeland. The book simply gives an account of events, which are intriguing enough in themselves; but another interpretation is possible, one that breaks through to a deeper level. The first-person narrator points to this alternative reading in a series of almost incidental remarks, such as “and if you want to write, you’ll find yourself grubbing around in his heart, which is your own heart, because that whole separation into two people is of course merely a pretense. Rather hard to comprehend, I fear.” Perhaps Slingeland is a facet of the author S.? One more step and both S. and Victor Slingeland (initials V. S.) become alter egos of the author Simon Vestdijk. A chapter title in the book’s sequel, “A Novel within a Novel within a Novel,” confirms that the reader is meant to explore these interlocking viewpoints. Vestdijk wrote three books about Victor Slingeland, and in all of them he plays an ingenious game with the relationship between fiction and reality. He is said to have been inspired by André Gide’s The Counterfeiters (Les faux-monnayeurs, 1926). This was certainly a theme new to Dutch prose in the late 1950s, and it anticipates later developments in deliberately non-mimetic writing.

The Fifties Movement

Historians have described the postwar years in the Netherlands as “a time of discipline and asceticism.” It was certainly not a time for experimentation. Paradoxically, it was precisely in these years that Dutch poetry went through a process of radical renewal.

It did not amount to much at first. Forum ideas still underpinned poetry, as they did prose. In practice this meant that intellectual and anecdotal elements predominated and passion was restrained. But divergent views slowly emerged. In 1950 a young Remco Campert (1929–) expressed his dissatisfaction with the current state of poetry in a poem in which he claimed it was high time “we make something heard, / a voice that cuts through the rubble-dust” and “blows the fuses of resignation.” Campert was clearly targeting the small-scale character of the poetry of the time. His verse forms were modern, in the sense that he was not concerned about rhyme or meter, although the imagery was far from revolutionary and even the title suggested hesitation: “Shouted Too Loud?”

Lucebert. Photograph: Chris van Houts.

The renewal might well have remained stuck there, were it not for the rise of a key figure, a poet who called himself Lucebert (1924–95). The pseudonym suggests both “bringer of light” and “Lucifer.” He gave a decisive boost to the initial stages of reform, much as Kloos had done at the start of the Movement of 1880. The comparison does not end there, since the experimental poets of 1950 were also named after a decade: the Fifties Movement.

In late 1948 the young Lucebert tried to sell his political drawings to a spread of different newspapers. In working through the various editorial boards he arrived at the Communist newspaper The Truth (De waarheid), where he met the poet Gerrit Kouwenaar (1923–). Kouwenaar wrote to a friend: “Here in my house a remarkable young man is lying asleep in rags. He draws and writes poems.” The raggedy youth scribbled away in a small notebook. One day Kouwenaar found a loose page that had fallen out and could not believe his eyes. Suddenly, here was what the young poets had been looking for, written on the torn out page of a tramp’s notebook. Lucebert was soon the charismatic central figure of a circle whose members became known as the experimentalists, or the Fifties Poets.

In fact it was Lucebert who gave the Fifties Movement its name. For him, as for Campert, the new poetry was about more than a purely literary revolution. The Fifties Poets wanted a change of climate and felt nothing but contempt for the sedate nature of Dutch society. Addressing the “ladies and gentlemen of letters” Lucebert wrote:

when you read blake rimbaud or baudelaire,

listen to our verse: their holy ghost runs there —

to kiss the naked arse of art beneath your sonnets and your ballads.69

“Kiss the naked arse of art”: it was this kind of earthy physicality that gave the language of the Fifties Movement its unique character. Their work provoked opposition from the start, as did their attitude. A public appearance by Lucebert in 1951, for instance, caused controversy. A fellow poet reported on the event as follows:

He began with a poem called “the illiterate” and then read out the a b c. He became angry with the audience and said, ‘You haven’t come here to talk, I’ve come here to talk.’ Then he tipped a glass of water over his head, having first put on a black mask. He took off the mask and read out a poem with a lot of cunt and cunts. . . . Finally he lit sparklers (ten for a quarter) and said, ‘Great, isn’t it? And it’s only cold fire.’ . . . Only the first two rows applauded; that was where the literati were sitting with their entourage.

A rightwing newspaper published a predictably indignant article about this “playful” event; others sneered that they’d seen such dadaist jokes before. Incidents like these were only part of the story, however. One poem by a Fifties poet consisting purely of sounds brought a protest from the Upper House of Parliament, where a conservative member expressed dismay that subsidies were being allocated to such “infantile drivel.” In 1953 an older poet asked himself whether perhaps the SS had marched in with the experimentalist poets. That same year the city of Amsterdam awarded its poetry prize to Lucebert. He dressed up as emperor of the experimentalists and went to the Stedelijk Museum, where he was refused access. The police intervened in a heavy-handed manner.

Scenes like this hardly encouraged readers to take the new poetry seriously, and few wondered what it was really all about. What did the new poets want? As always with questions like these, it is easier to show what the new poetry had pitted itself against. The most prominent characteristic of the Fifties Poets was their anti-intellectualism. Lucebert began a poem called “Little Textbook of Positivism” with the verse:

that philosophy let it go

three dead thoughts

in a grey-leather skin

afloat on a fug of words70

The movement wanted nothing to do with dead theory. They asserted the importance of the flesh, in other words of the body rather than the mind. With their resistance to intellectualism, the Fifties Poets were moving closer to the prose writers of their day. In Reve’s The Evenings, as we saw, man is reduced to a physical body and the novel lacks any intellectual dimension. But although poets as well as novelists saw man first of all as a physical being, there are differences. In a book like The Evenings the focus is on bodily deficiencies and imperfections: sickness, baldness, and so on. The bodily experiences described by the poets are much more festive, as in the opening stanzas of “Lying in the Sun” by Hans Andreus (1926–77):

I hear the light the sunlight pizzicato

the warmth converses with my face again

again I lie not so you’d better start so

again I lie obsessed while light stuns my dumb brain.

I lie full length lie singing in my skin

sing soft replies to sunlight’s repartee

lie dumb yet not so dumb not letting people in

sing things about the light around and over me.71

We are unlikely to find sun worship of this kind in the “fiction of disillusionment” of the time. And there is another difference: Reve, Hermans, Blaman, and others write sentences with a logical progression, whereas the Fifties Poets invented a new idiom. The physicality of the body also pervades the imagery, so that we repeatedly come upon lines like “I have arms to my brain,” “We listen with our hands,” and “Think with tongue and hands.” Words too are physical, and even the poem ought to have a body, or to be one. As Jan Elburg (1919–92) wrote:

I’m cussedly just of flesh

and the poem’s

not made of blood and muscle

more’s the pity72

Since for the Fifties Poets everyday language was contaminated, the shrieking vocabulary of newspapers and careless everyday speech, they went in search of a “language of Adam,” as described by the only essayist among them, Paul Rodenko (1920–76). He characterized the poetry of the experimentalists as

an attempt to take the language back from the specialists; they achieve this by using neologisms, unusual word combinations, and bizarre images, by the destruction of grammar, the interjection of meaningless sounds, etc., in short through techniques aimed at stripping language of its functionality, its utility value — with the intention, of course, of restoring language to its primal state, reduced to raw material, so as to create a new language, a new poetry, a new space; not just another kind of poetry, different upholstery for the same space, but a truly new language like that of Adam, the first man, in a truly new space, with a scent like that of the “first morning.” And if the very first morning, the very first language, that of Adam, remains irretrievable because of the fall — because we have become people of culture for ever — well, one can still try to create a language and a space as young and unsullied as the child who, with a new slate pencil and a clean slate, steps into Culture for the first time.

One of their most striking methods in the quest for a language of Adam is the use of so-called autonomous images. In the poetry of the experimentalists images no longer “stand for something else,” rather they create their own reality. Lines like “against the pulse of the stone / beats the thought of the hand” do not allow the image to be connected with any conceivable corresponding object. Of course, such puzzling images occur in older literature as well, but in Lucebert and his fellow poets they are much more common than in any of their predecessors. It is precisely at the point where logic becomes disjointed that the experimental nature of modern poetry reveals itself: the connections it establishes lie far beyond the world of everyday experience.

The emergence of the Fifties Poets can be explained in various ways. There was certainly a need to catch up. The Netherlands, a neutral backwater during the First World War, had seen little avant-garde activity in literature: some expressionism in Hendrik Marsman, who always hovered between tradition and innovation; a single dadaist in I. K. Bonset (Van Doesburg); no surrealism at all. Vague attempts at avant-garde work in the 1930s had been stifled by Forum and the sheer seriousness of the period. Now, at last, the country was witnessing a breakthrough similar to the one that had taken place in other European countries in the 1920s and of which Paul van Ostaijen had been the leading proponent in Flanders.

But to regard the Fifties Movement as making up lost ground would be to dismiss it as Dada après Dada, as indeed some contemporary critics did. The reality is more complex. Lucebert claimed that the new poetry distinguished itself by its novelty. This can be applied to the physicality that is such a striking feature of the new imagery. In contrast to the interest in bodily imperfections typical of fiction writers after 1945, the Fifties Poets invite us to feel the celebratory vitality evoked by Lucebert in a poem dedicated to the sculptor Henry Moore:

it is the earth that drifts and rolls through the people

it is the air that sighs and breathes through the people

the people lie inert as earth

the people stand exalted as air

out of the mother’s breast grows the son

out of the father’s brow blooms the daughter

wet and dry as rivers and banks their skin

as streets and canals they stare into space

their house is their breath

their gestures are gardens

they shelter

and they are free

it is the earth that drifts and rolls

it is the air that sighs and breathes

through the people73

While the experimentalist poets were certainly at the center of attention in the 1950s, there were several important poets who did not belong to the movement. Some used traditional verse forms such as the sonnet but with entirely new content. Most prominent among them was Gerrit Achterberg (1905–62), who had made his debut before the war (and was discussed in the previous chapter). Achterberg was the only Dutch poet the Fifties Movement wholeheartedly admired, and his postwar work showed a broadening of his immediate concern — reaching across death to his deceased beloved — into a quest for God, the beloved, and the perfect poem. This extremely ambitious approach was balanced by the apparently unpoetic material he took as a starting point, reflected in titles like “Asbestos,” “Gristle,” “Plastic,” and “Gravel.” His later work, marked by a preference for the formal restraints of the sonnet, managed to give a metaphysical sheen to everyday things, as in the following lines from a sonnet about a famous department store:

Dots move about in a primeval state.

A Vitus dance of men and women churns

and seethes to yield you up. High priests libate

a brand-new scent. On altars, incense burns . . .

The names reverberate, tannoyed out loud.

Meneer Van Dam is somewhere in the crowd:

you might be too at any time, I guess.

Then I shall go across to the cashier,

inquire after you, just to appear

polite, and tell the shop girl my address.74

The First Morning

In Flanders, too, the revolution represented by experimental poetry claimed center stage in the 1950s. In 1949 the magazine Time and Man (Tijd en mens) was established, a publication explicitly opposed to the neoclassicist restoration that had taken hold in Flanders in the 1930s. “In poetry we will seek out afresh the intuitive hallmarks, rejecting the current Flemish tinkering that people are pleased to call neoclassicism,” the editors declared in the inaugural issue — the word “afresh” in their statement suggesting a return to Paul van Ostaijen and the humanitarian expressionists. Intuition would be the chosen weapon to combat metrical verse and traditional content. Time and Man also rejected another aspect of neoclassicism, the appeal to eternal beauty. “We reject theories that detach people from the influence of time; instead we want to zero in on both time and the individual,” they declared. Even the magazine’s name, reminiscent of Sartre’s controversial mouthpiece Les Temps Modernes, suggested a program: Time and Man intended to take a stance vis-à-vis the problems of the postwar period and to give a voice to the young, those “who were twenty in 1940 and raised not by professors but by the war.” The experience of war had made a non-committed art focused on eternity impossible.

In this approach, with its emphasis on engagement, the hand of one of the magazine’s founders, Jan Walravens, is clearly recognizable. He was to become the driving force behind Time and Man. Even before 1949 he had written an essay in which he stated quite unambiguously that Flemish literature would only become great “if it can manage to provide an answer, in its own forms, out of its own circumstances, and with its own vision, to the great need and great fear of these times; only then will it interest the world.” Grand words indeed, but this was apparently the era for such words.

Although Time and Man also published prose, including that of Maurice D’haese, Louis Paul Boon, and enfant terrible Hugo Claus, its primary contribution was in the field of poetry. Among its young and talented poets was Ben Cami (1920–2004). In The Land of Nod (Het land Nod, 1954) Cami points to the biblical figure of Cain, the archetypal man without faith, who is evoked in an atmosphere of oppressive emptiness:

No one hears the flow of time as it spumes

Across the rocks which we call towns, in a spate

Which scours the words and pictures from the rooms

Of all that we adore and execrate.

In the sand a skull, an axe of stone,

Which nobody will see.

Wind on the water, light of sun,

A god who starts again, reluctantly.75

The form is such that this could certainly be called experimental poetry, despite the absence of a feature that dominates most other poetry in Dutch at this time: imagery of the human body. As a result Cami’s words have a defiant quality, as in the lines:

And if you’re lonely or afraid

In face of merciless eternity

Refuse all comfort:

Man, incarnate question.76

In Cami’s work this “incarnate question” — a bodily image, an exception to the rule — always takes the form of an individual who stands in opposition to tyranny, corruption, and other maladies of modern society.

In 1955 Walravens published an anthology of new Flemish poetry, Where Is the First Morning? (Waar is de eerste morgen?). Like Paul Rodenko, who had recently compiled the anthology New Pencils, Clean Slates (Nieuwe griffels, schone leien, 1954), Walravens placed experimental poetry in a historical context. He started by quoting Guido Gezelle, followed by several poems by Paul van Ostaijen, before finally arriving at the new generation. The brief introduction laid out the basic assumptions of the new poetry. Only irrational images could do justice to “the reality of modern humanity.” These images were not an added bonus, as in traditional poetry; they constituted the poem itself. Walravens further stressed the specifically Flemish character of the poems in his anthology: “The Flemish modernists talk about the reality of these times rather than their own individual pleasures and sorrows.” This, he argued, set them apart from the Dutch poets: whereas the Flemings were driven by ethical concerns, in Holland the movement was “more youthful, more turbulent, but also more aesthetic.” The observation proved highly influential, the contrast becoming an accepted part of literary history.

Nevertheless, by no means all the poets in Time and Man can be described as ethically committed, as is clear from the work of the greatest among them, Hugo Claus. Claus quickly recognized that the triumphant new Flemish poetry had clichés of its own. In a letter to Walravens in 1954 he wrote: “I hope you’ll forgive me, but when I read ‘the arteries of the will,’ ‘the bird of your eye,’ ‘the blond dune of the sun,’ I feel dreadfully tired. I turn puritan when I’m given these things to read, and I long for the strictly disciplined alexandrines of Count August von Platen.” These objections are typical of Claus in a dual sense: in the incisive way he captures the new-fangled imagery, but also in his longing for classical poetry, which speaks volumes. The young Claus is declaring himself an eclectic, unwilling to commit to any tradition, even the “modern.”

Claus’s widely acclaimed collection The Oostakker Poems (De Oostakkerse gedichten, 1955) demonstrates how, at an early stage, he forged a means of expression as compact as it was complex. There is a discernible “story” running through the collection: a young man extricates himself from his background and environment in order to devote himself to an intense loving relationship with a woman, even though ultimately he comes to experience this relationship as a new form of coercion. The love story reflects the changing seasons, from spring to summer to winter. The title refers to the village of Oostakker, not far from the city of Ghent, where Claus’s parents were living at the time. The significance of Oostakker is not merely autobiographical, however. The village is known as a place of religious pilgrimage, where sick believers come to seek a cure. The poet has no faith in its curative properties; instead he tends to locate all maladies in his parents, who take on mythical qualities. His mother becomes a Virgin Mother, and religious and erotic connotations become entwined. These lines from Claus’s most famous poem, “The Mother,” give an impression:

When your skin screamed my bones caught fire.

You laid me down, I can never rebear this image,

I was the invited but slaying guest.

Now, later, I’m a strange man to you.

You see me coming, you think: “He is

The summer, he makes my flesh and keeps

The dogs in me awake.”

While you stand dying every day, not together

With me, I am not, I am not but in your earth.

In me your life rots, turning, you do not

Return to me, and I will not recover from you.77

Around 1955 experimental poetry spread like an inkblot as modern verse proliferated in a variety of magazines. Nevertheless, tradition retained a significant presence. Among its advocates was one particularly complex figure, Christine D’haen (1923–). While some see her as a representative of traditional poetry because she uses well-established poetic forms, others emphasize her “exuberant mannerism,” suggesting she has more in common with some of the experimental poets. All agree that she looks to the Western tradition, dominated by its classical and Christian inheritance, as a source of values. Although D’haen’s poetry sometimes features everyday objects, they are always given mythical or symbolic weight. Her work is a prime example of the unfashionable tradition of craftsmanship that does not shy away from deliberate artificiality.

The magazine Gard Sivik (1955–64) situated itself between these two currents, the avant-garde and the consciously traditional. Here we find the work of Paul Snoek (1935–81), who made his name with the collection Hercules (1960) and built on the achievements of the experimentalists without ever lapsing into incomprehensibility. This helped to make “A Swimmer Is a Horseman” a much anthologized poem; its first two verses can serve as an introduction to the whole of Snoek’s work:

Swimming is dissolute sleeping in floundering water,

is making love with every available pore,

is being infinitely free and mastering within.

Swimming is probing loneliness with fingers,

is telling ancient secrets with arms and legs

to the always omniscient water.78

This is not the only poem dominated by the presence of water. For Snoek water is a fundamental principle, the primary creative element, in which opposites merge, gravity seems suspended, and a person is free. In the third verse of “A Swimmer Is a Horseman” the narrator states explicitly: “In water / I am a creator embracing his creation.” Poetic and erotic accents blend together in the extraordinarily physical, triumphant image of a swimmer riding the waves. The poem’s last sentence is set apart: “Swimming is almost being somewhat holy.” This sacral element recurs throughout the collection. To Snoek a poet is a prophet, a concept entirely in accord with Romantic tradition, and indeed the volume’s title gestures toward a (no less Romantic) cosmic self-aggrandizement: Hercules performed superhuman acts. But it closes with a rather less joyful poem, “Living on Earth,” which evokes a race of humans who

tread on the sea, but without wings

could not be naked and called up gods without will

in order to meekly, yet more lonesome, discover the wound

that death is the oldest sin of the earth.79

These lines are reminiscent of the empty landscapes of Ben Cami. In other words, in Snoek’s work, alongside the romantic embrace of life, a somber existentialist worldview looms large, as it does in many other poets and novelists of the time. We encounter the same dualism, a sensual acceptance of life contrasting with a deeply depressive tendency, in the Dutch experimental poet Hans Andreus.

Snoek had started out as one of the driving forces behind Gard Sivik, but gradually the character of the magazine changed. In 1961 Snoek left the editorial board, and Gard Sivik became an outlet for Dutch “new realism,” a very different phenomenon. In 1963 Jan Walravens concluded that “the hour of experimentation has passed.” Others came to the same conclusion. What annoyed the once experimental poets most of all was that, paradoxically, experimental poetry had become entirely acceptable: “Professors devote their lectures to it, anthologies come thick and fast, . . . official prizes are awarded to poets who write this way (when only yesterday the same jury members ridiculed them).” Paul Snoek observed sadly that “the Fifties poets are being taught in schools.” It is a pattern familiar to modern art: whatever enters the mainstream loses its power and necessitates a countermovement. And so, the challenging nature of much experimental poetry led to calls for an art that was easier to understand, for a “democratization of art” as it would be called in the populist 1960s. A fresh chapter had opened in the history of poetry.

II. The Revolution of the Sixties, 1960–1970

Anne Marie Musschoot

The 1960s ushered in an economic boom and set the stage for a new society, a consumer society characterized by broadly based anti-authoritarian movements, a liberalization of moral norms, and a playful atmosphere in which people believed that, as the saying of the time went, the imagination should seize power. The sixties were years of revolutionary slogans and critical questioning. Art became a form of critique, and artwork as such came under fire; it was dislodged from its isolated, elitist position as a message for the happy few to become a product of collective activity and deployed as a means of changing society.

Consistent with this atmosphere of general protest, a new phenomenon arrived, that of the “happening,” which was introduced to the Netherlands in 1959 and for a while put pressure on the notion of art as a form of individual expression. The poets C. B. Vaandrager, Hans Sleutelaar, and Armando produced a manifesto preaching “permanent revolution” and proposing, in a gesture inspired by Dada, the closure of all museums and the destruction of all the artworks held in them. The call represented merely the latest attempt to abolish existing art or radically reform it, except that it took resistance to established art further than ever. The intention was now to abolish art as such for being elitist and to merge it into a broader social event in which the artist would be wholly indistinguishable from the non-artist. This was the logic that led to everyday items (known as ready-mades) being elevated to the status of art or at least integrated into it. As a result, the previously marginal phenomenon of American pop art, itself an avatar of Dadaism, became public property in the Low Countries as it was elsewhere.

This critical, anti-authoritarian way of thinking gave rise to the Provo movement in Amsterdam in 1965. Its playful guerrilla tactics were underpinned by a political anarchism that aimed to destabilize the consumer society it despised. Provo was a youth movement, using disturbances of the peace, or provocation, as a conscious political strategy designed to bring about social change. Quick to join this “Provotariat” were students, artists, and writers (including Harry Mulisch) who had turned against the law-abiding middle classes and declared their solidarity with the workers in their social struggle. The Provo movement had been officially disbanded by the spring of 1967, but by then the fuse had been lit. Spearheading the attack on bourgeois values and institutions were leftwing students, who set up numerous “extra-parliamentary” opposition groups in line with international student syndicalism and inspired by the revolutionary beliefs of the philosopher Herbert Marcuse (author of Eros and Civilization, 1955 and One-Dimensional Man, 1964) and the Frankfurt School. This resulted in spectacular student occupations at universities in the Netherlands and Flanders in 1969.

The most noticeable concrete result of these widespread democratizing tendencies was the dissolution of boundaries and hierarchies, even in novels and poetry. The dividing line between art and reality became blurred, and traditional literary structures were dismantled, including definitions of specific genres. The most dramatic change became known as the trend to “defictionalize” literature. While, following the example set by Marcel Duchamp, ready-mades were introduced into the visual arts, including the graphic work of Louis Paul Boon, and street sounds were integrated into music in the manner of John Cage, poets started to make use of preexisting “texts” or everyday pieces of writing; J. Bernlef (1937–), for example, presented a shopping list as a poem. The novel was stripped of its fictional quality by the introduction of non-literary elements intended to puncture the illusion of reality, such as the authentic archival documents used by Sybren Polet. Authors turned away from traditional narrative techniques that created the illusion that a real world was being evoked.

New Realism in Poetry

New realism was introduced into poetry in the early 1960s in the Flemish magazine Gard Sivik. When its editorial board was expanded in 1957 to include the Dutch writers Hans Sleutelaar (1935–) and Cornelis Bastiaan Vaandrager (1935–92), the impact of new-realist principles became increasingly visible, and the group began to define itself by its opposition to the Fifties Movement. One issue in 1964 announced “a new date in poetry” and featured on its cover a road sign reading “50” with a red line running through it. The poets of the sixties resolutely turned to face the everyday world around them and appealed for an exclusive focus on the ordinary. Although experimentalists like Lucebert, Jan Elburg, and Gerrit Kouwenaar were recognized as innovators, they were accused of helping to promote the traditional Romantic image of the artist. “The Fifties Poets, they were bohemians after all, so a large part of reality escaped them, a large source of richness,” as Armando put it later in an interview, and Sleutelaar pointed out that the new generation, with its background in journalism and advertising, had repaired the breach with established society opened up by the Fifties Movement. In the issue of Gard Sivik announcing “the end of the fifties” Armando expressed the new approach as follows:

Do not moralize Reality or interpret (artify) it, but intensify it. Starting point: always accept Reality. Interest in a more autonomous role for Reality, as already seen in journalism, television reports, and film. Working method: isolate, annex. Result: authenticity. Not of the maker but of the information. The artist, who is no longer an artist; a cool, businesslike eye. “Poetry” as the result of a (personal) selection from Reality.

The same points were emphasized in the magazine Barbarber, which ran from 1958 to 1971. Although a number of its contributors, such as Jan Hanlo (1912–69), at first continued to work in the tradition of the Fifties Movement, they evolved away from “excessively esoteric” writing that took itself too seriously and instead returned to reality. Barbarber presented itself from the start as a “magazine for texts.” It initially appeared in stenciled and thus “democratic” form, implying that the boundaries between literature and non-literature had been abolished: everything that existed, everything that could be observed, belonged to the domain of poetry.