1: The Middle Ages until circa 1400

Frits van Oostrom

The history of literature in Dutch begins with a poet who is known to us only from secondary sources, who belonged to both the pagan and Christian cultures, and who sang both psalms and epic verse. That this first-known poet from the Low Countries, Bernlef, was afflicted with blindness endows him with a certain Homeric quality — so there is every reason to choose him as the starting point of this literary history.

Bernlef

In his hagiographical life of the eighth-century Christian preacher Liudger, who died while doing God’s work in 809, the Frisian bishop Altfried (died 849) relates that this man of God, while traveling through Friesland to spread the gospel, was once invited to share a meal with a noblewoman in a village near Delfzijl. “And behold: while he and his followers were seated at the table, a blind man, one Bernlef, was brought before him, who was much loved by all the neighbors for his striking good nature, and for the marvelous way in which he sang about the heroic deeds and the wars of the Frisian kings. But this man had been struck down three years earlier with total blindness, which deprived him permanently of even the smallest ray of light.” Naturally, Saint Liudger was able to restore Bernlef’s sight, and he explained that this blessing was in fact God’s doing. For the rest of his life, Bernlef would place his charisma in the service of his Christian mission, teaching, performing baptisms, and chanting psalms.

When he approached his end, and his wife asked him, weeping, if she would ever be able to live without him, he jested, “If I can induce the Lord above to grant me a favor, you will not live much longer in this world.” When she heard this, the woman was still hale and hearty, and yet she died two weeks later to keep her husband company.1

This splendid story is set in the northeasternmost region of today’s Dutch-speaking territory. Bernlef, the singer, was Frisian. We shall frequently be obliged to look to Friesland for the earliest written Dutch texts. Take the oldest legal texts in Dutch, for instance. Written in Friesland, they were compiled to codify the Teutonic customary law that had been observed in these regions for centuries, and that would only slowly undergo transformation into the more abstract law fashioned on the Roman model. For literary historians, this transition is almost regrettable. For although Roman law excels in cogent abstractions — excellent for legal matters, but couched in the dry phraseology of clerks — customary law is notable for its highly expressive, at times almost poetic, descriptions. Here are the graphic words used to describe the marriage ceremony between free Frisians: how dio frie Fresinne coem oen dis fria Fresa wald (the free Frisian woman emerged from the free Frisian forest), mit hoernes hluud ende mit bura oenhlest (to the sound of trumpets and the shouts of neighbors), mit bakena brand ende mit winna sangh (with bonfires and the singing of friends), ende hio breydelike sine bedselma op stoed (and climbed onto his bed as his bride), ende op dae bedde herres lives netta mitte manne (and used her body with the man on the bed). Some phrases possess true poetic beauty, such as those describing nightfall: als dioe sonna sighende is ende dyoe ku da klewende deth, meaning “when the sun sinks down and the cows turn their hooves,” that is, lumber back to the cowshed.

So Bernlef was certainly not the only Frisian poet of his time. His region was highly developed in the early period we are considering. This included cultural development, an area largely dominated, of course, by the exchange of paganism for Christianity. In Bernlef’s day, great preachers, many of them from the Anglo-Saxon territories, sacrificed their lives to secure Christianity’s victory. The most renowned of these is Boniface, whose martyr’s death in Dokkum in 754 is one of the lieux de mémoire of Dutch culture. One or both of the parents of Bernlef, who was born c. 750, may well have heard this impressive man of God preach. That they converted to the new faith immediately upon hearing him speak is rather unlikely, given the degree to which their son would later cherish the old traditions. In fact the kind of radical conversion so favored in narratives of early saints’ lives, with heathens jettisoning their darkness for the new light without a second thought, was generally quite rare. In many cases Christianity gained the upper hand only very gradually, and actually coexisted with certain forms and aspects of Germanic polytheism for many years.

Bernlef himself appears to be a good example of this coexistence, since he was presented at the banquet for St. Liudger as an outstanding singer on the martial exploits of the Frisian kings. Among the Frisian elite gathered around the table — especially among the more culturally minded women, perhaps; it may not have been mere coincidence that Liudger and Bernlef had been invited by a noblewoman — a good discussion about true Christianity appears to have been entirely compatible with songs extolling Germanic heroism. Bernlef himself, whose fame seems to have rested largely on his superb voice, turned out, when he met Liudger, to be fully apprised of the new doctrine; the preacher’s inspiring words gave him the added impetus that precipitated his definite conversion rather than suddenly revealing to him the absolute truth. Meanwhile, the fact that Bernlef saw the light, quite literally, at this point in time, is certainly the pivotal element of this story; and Altfried creates the distinct impression that the poet confined his repertoire to Christian texts after that date, abandoning songs on Frisian kings for the Psalms of David.

But is this really true? Or were not the songs celebrating Germanic heroism far more tenacious, in Friesland and elsewhere, while Christianity gained ground only slowly and in fits and starts? That certainly seems a reasonable assumption, though it is also a frustrating one, since not a scrap has been preserved of the centuries-long tradition of Germanic literature — before, in, and undoubtedly after Bernlef’s day — and the hundreds, if not thousands, of texts of which it must have been composed. We have nothing either by Bernlef or by any of the numerous bards like him. The situation illustrates the difference between medieval and modern concepts of literature. To us, literature is wholly and inextricably tied to books. But in the Middle Ages, certain prominent forms of verbal artistry existed quite separately from books, however inconvenient it may be for literary historians who, without books, are left empty-handed. At the same time, the Middle Ages have given us so many literary books that historians are hard put to deal with them all. But like the life of Bernlef that has come down to us indirectly, these extant texts emanate in the first place from the culture of Christianity, which did more than anything else in Europe to produce a literature of books in the vernacular, and they were written in Latin, the lingua franca of medieval ecclesiastical culture.

Vernacular Writing and Oral Culture

The earliest recorded examples of what may be called literary Old Dutch illustrate the subordinate position of the vernacular compared to Latin. Characteristic examples include the so-called Wachtendonk Psalms, a corpus of some twenty-five psalms with a very complicated history of transmission, whose origins can be traced to the Moselle-Frankish region in or around the middle of the ninth century. Shortly afterwards, it seems, this translation of the psalms was adapted by a writer from the Lower Rhine region. Although some manuscripts present the Dutch text as a more or less independent Psalter — and patriotic philologists have sometimes helped to strengthen that impression — the Wachtendonk Psalms appear to have been written as an interlinear translation, that is, a Psalter in which each Latin verse was followed by a word-for-word equivalent in the vernacular. One surmises that a work of this kind would have been produced by schools, where boys of the early Middle Ages learned to read and write in Latin. Once schoolboys had mastered the alphabet, their standard elementary textbook was the Psalter. Where else was such a sublime combination to be found of syntactic simplicity, poetry, piety, and verse that was easily committed to memory? It seems obvious that in order to teach an understanding of Latin at this basic level, teachers will frequently have turned to the boys’ mother tongue, the vernacular they spoke at home (only to exchange it at the monastery for Latin, the language of the church). The numerous interlinear translations of the psalms appear to owe their existence to this interaction between the vernacular and Latin in medieval schoolrooms. In other words, Dutch verses of this kind were written primarily to explicate the Latin, and certainly not as independent literary creations. This does not detract from their interest to literary history, just as there is also an unmistakable charm about these lines, strung together into a ninth-century Dutch version of Psalm 1:

Blessed [is the] man who walks

(Salig man ther niweht vor in)

not in the counsel of the ungodly

(gerede ungenethero)

and stands not in the way of sinners,

(inde in wege sundigero ne stunt,)

and sits not in the seat of scorners,

(inde in stuole sufte ne saz;)

but in the law of God [is] his will,

(navo in ewn godes wille sin,)

and on his law he shall meditate

(inde in ewn sinro thenken sal)

day and night.2

(dages inde nahtes.)

Other examples of early Dutch literary endeavors can be found hidden away, quite literally, in the margins of Latin, the official and normative language. The notion of “Dutch,” incidentally, is an anachronism here; in fact there was only one Germanic language between the Lower Rhine and the English Channel (and to some extent even on the other side of the Channel), with an endless gradation of dialects. The Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris possesses a tenth-century manuscript of the Psychomachia by the early Christian author Prudentius, a poem that describes the struggle between Good and Evil inside every human being and was frequently read in classrooms. The text is accompanied by Latin and sometimes Germanic glosses, faded and barely decipherable, in the most delicate handwriting. While doing this work, however, the glossator must have been living in the Romance-language area; perhaps he was completing his studies in the famous abbey of Corbie. One of his glosses bears witness to his contact with Francophones: his annotation, at Prudentius’s acus [coast] reads: quem Latini kotem dicunt [which the French call côte]. In the same vein, Germanic glosses can be found in an eleventh-century manuscript from Saint-Omer, of the early Christian historian Orosius, and in two early manuscript bibles from the Groningen and Westphalia regions. In every case the vernacular served only to underpin the understanding of Latin, most probably that of schoolboys and students. At this stage the prospect of anything that might be called a home-grown Dutch literature still seems very remote indeed.

Another shared feature of the above examples is that they originated from near, or even beyond, the borders of the current Dutch-speaking region. The same might be said of our final example, since it must have been written in Rochester Abbey in Kent. But whereas the other texts betray echoes of eastern dialects, this text resembles very old southwestern Flemish. Partly for this reason, it has been known since its discovery in 1933 as the prime example of very early Dutch literature. More saliently, its reputation springs from the fact that it is couched not in the phraseology of bookish glosses but in undiluted literary language. The lines in question appear to be the opening lines of a love poem:

While all the birds are making nests

(hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan)

Still you and I demur;

(hinase hic enda thu;)

What are we waiting for?

(wat unbidan we nu?)

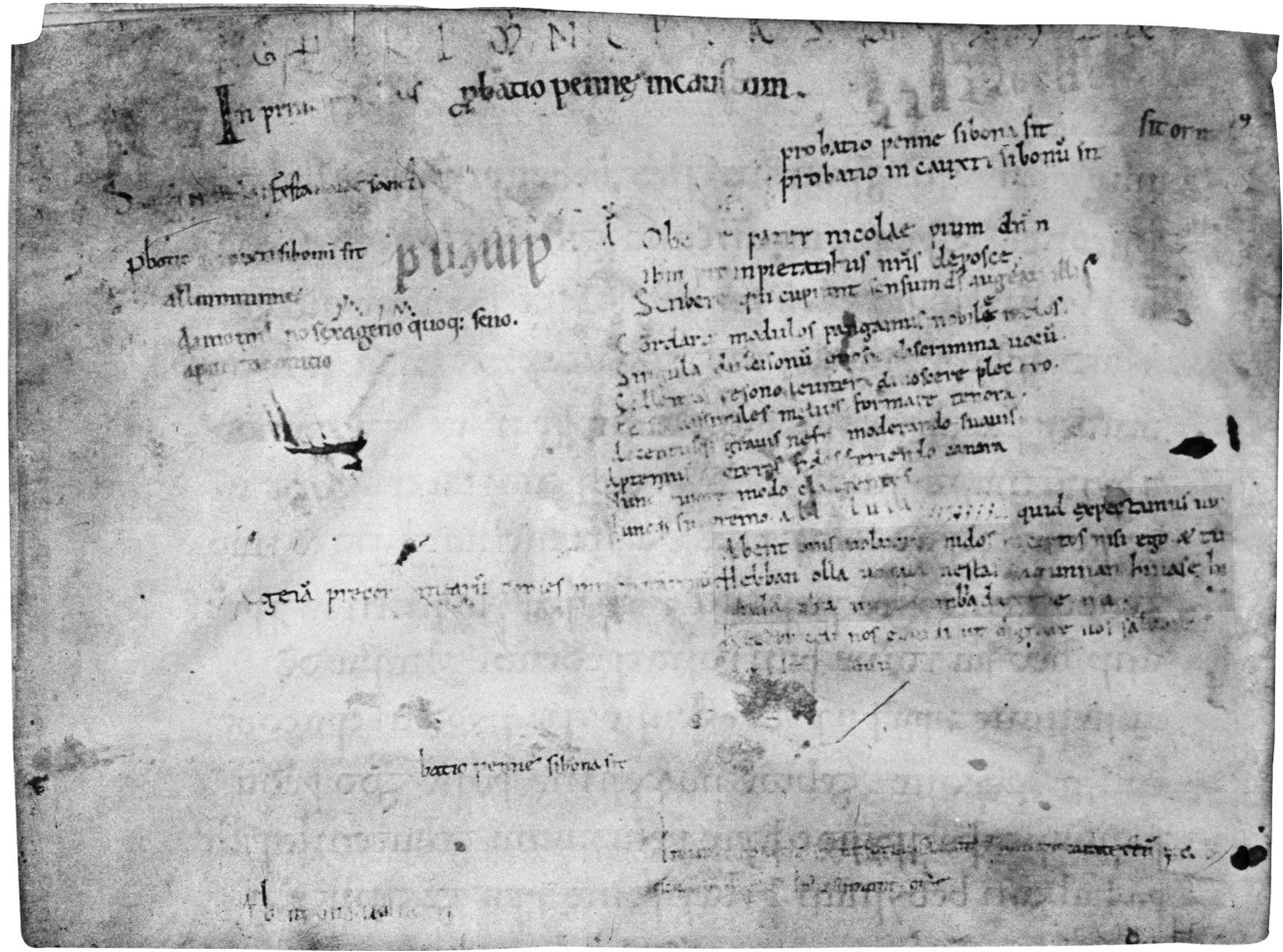

Here, too, Old Dutch literature blooms in the shadows of scholarly Latin culture. The lines were entered on the flyleaf of a manuscript (now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford) containing Old English sermons by Aelfric and written as a probatio pennae, a few lines of writing to test the quality of a new quill pen. Only to prevent himself from ruining what was truly important, the sermons, did the scribe jot down a few lines from memory. Our priorities, some nine centuries later, are very different, and Dutch literary history would happily forfeit the learned sermons for another such fragment as Hebban olla vogala. It may be that the little inscription attracted attention even in its own day because of its striking difference from the stereotypical probatio pennae. In any case, the Old Flemish lines of verse are accompanied by their literal equivalent in Latin: habent omnes volucres nidos inceptos nisi ego et tu — quid expectamus nunc.

“While all the birds are making nests” (“hebban olla vogala”), lines on the flyleaf of a manuscript in Oxford. Oxford, Bodleian Library.

But make no mistake: the Flemish words should not be regarded as glosses, like the earlier texts that were written solely to clarify the Latin. This time the roles are definitely reversed. Analysis of the script has proved beyond doubt that the lines in the vernacular were written first, the Latin being a later addition, possibly to explain to the community of largely English monks what their Flemish brother had written. That a Flemish monk should have been living in Rochester was not as strange at the time as it might seem today. A generation after William the Conqueror had crossed the English Channel, there was still a lively to-ing and fro-ing of people and goods between the south of England and coastal areas of the continent. Some of William’s followers had even settled in England after 1066. Who knows, perhaps memories of their native language came all the more easily in the diaspora? In any case, the annotation of Hebban olla vogala must have been based on the memory of a Flemish monk who had ended up in English parts. Thus, completely by chance, a precious shell was washed ashore from a sea of Old Dutch texts and fragments of oral culture, most of which were lost irretrievably, never having been recorded in script. What is more, recent research has shown that these salvaged lines are what is known as a Frauenstrophe, a type that in many literary traditions features among the earliest extant lyrical poems. Hebban olla vogala evokes not stereotypical male urgency, but female desire.

We can conclude that, although the texts that have actually come down to us often suggest otherwise, this early Dutch “literature” was no mere derivative of Latin texts. There must have been rich, vigorous traditions of songs, and certainly of stories. That we seldom see any concrete examples of them should not lead us to underestimate their quality or quantity. In that sense, Hebban olla vogala resembles a tiny fossil which a trained eye may recognize as the relic of a vast history. This is the condition in which we find the earliest literature in the Dutch language. It is a paradoxical condition: the texts that were written down can scarcely be called literary, not even in the broad sense generally used by medievalists. They are consistently phrased in utilitarian language and written in the service of Latin. But outside books, a wealth of Dutch literature must have existed, and even flourished.

Other precious fossils pointing in this direction lie concealed in the history of names. Official documents tell us that, in the Ghent region, shortly after 1100, some noble families named their sons after the heroes from the stories surrounding King Arthur and the Round Table. Thus we find an Ywein of Aalst and a Walewein of Melle; the given names are the Dutch equivalents of Arthur’s knights Yvain and Gawain. This is not in itself a unique phenomenon: we encounter scores of Tristans, Lancelots, and Waleweins throughout the Middle Ages and even later. What is spectacular about the Arthurian newborns in Ghent, however, is that they arrived so early: half a century before Chrétien de Troyes recorded the first literary Arthurian romance, and long before Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae, commissioned by the king of England, was accepted as proof of King Arthur’s historicity in continental Europe. Long before this, it seems, there was a richly variegated narrative tradition surrounding King Arthur and his Round Table, in Dutch and in the Low Countries as elsewhere, before the material was legitimated through literature written in the vernacular.

This last factor is of the greatest importance for the medieval literary history of all the European languages. In the course of time, in particular in the twelfth century, the book became the primary medium for recording not only the Latin of church and scholarship but also, in due course, a sophisticated literature in the vernacular for the laity. The key element that determined this major breakthrough, in the Low Countries as elsewhere, was the close collaboration of learned clergy and ambitious nobles, with the latter eagerly devouring the writings of the former. In this cultural intercourse between nobles and clergy, the secular clergy occupied a central mediating role: as men of both church and world, they had the necessary intellectual baggage to liaise between the two. In France, where it began, this development is linked to the appearance of the so-called romans antiques, notably Roman d’Eneas and Roman de Troie. The Germanic-language area, too, produced a courtly romance on Aeneas in that early period. Its poet also wrote subtle courtly lyrics and an animated life of a saint, and merits a place of honor in the present literary history as the first truly distinctive author: Hendrik van Veldeke.

Hendrik van Veldeke

Much ink and energy was once expended on debating whether Hendrik van Veldeke belongs to Dutch or to German literary history. There is ample reason for such a controversy to have arisen, since literary history is rooted, as a genre, in nineteenth-century ideas of nationhood. In every self-respecting European country, authoritative scholars set about writing literary histories to show how, over the centuries, literature had been instrumental in shaping the nation and in demonstrating and displaying the nation’s identity. Literature served as the sheet anchor of the sense of nationhood. As early as the eighteenth century Thomas Warton’s History of English Poetry set out “to pursue the progress of our national poetry, from a rude origin and obscure beginnings, to its perfection in a polished age.” In such a model, every nation claims exclusivity for its great sons. Academics with a more international cast of mind have less trouble accepting that the literary tradition bequeathed by Veldeke has seeped into the cultures of several “nations.” Seen from this vantage point, Veldeke indeed epitomizes the absurdity of allowing our concept of medieval literature to be dominated by anachronistic views of national and linguistic frontiers.

Veldeke’s place of honor in German literary histories is wholly justified. As early as the Middle Ages great German poets such as Gottfried von Strassburg venerated him as their predecessor; Gottfried even says that it was he who inpfete daz erste ris in Tiutscher zungen, “grafted the first twig in the German language.” It is an apt metaphor, since Veldeke’s pioneering work consisted in transplanting material already firmly rooted in Latin and French literature. His saint’s life was based primarily on Latin sources. His lyrical verse relied on poetry written by the troubadours of northern France. For his Eneid he drew on the abundant sources from antiquity, but as channeled through the French Roman d’Eneas; Veldeke’s adaptation of the latter, appearing less than a generation after the French text, would be disseminated widely in a Middle High German form.

On the Middle Dutch side, Hendrik van Veldeke’s character is less strongly drawn, but his work appears to have been influential here too. This is most obvious in the case of his Life of St. Servatius (Het Leven van Sint Servaes), which, as evidenced by the only complete extant manuscript, must have been read in Maastricht well into the fifteenth century. The Eneid appears to have been known, at least roughly, to the great thirteenth-century West Flemish poet Jacob van Maerlant (discussed later), while the stanzaic poetry of Hadewych, the mystic from Brabant, to which we shall turn in a moment, exhibits parallels with Veldeke’s lyrical poetry which may reflect his influence. So although there is a less obvious continuity on the Dutch than the German side, Veldeke’s involvement in the beginnings of early Dutch literature is highly probable.

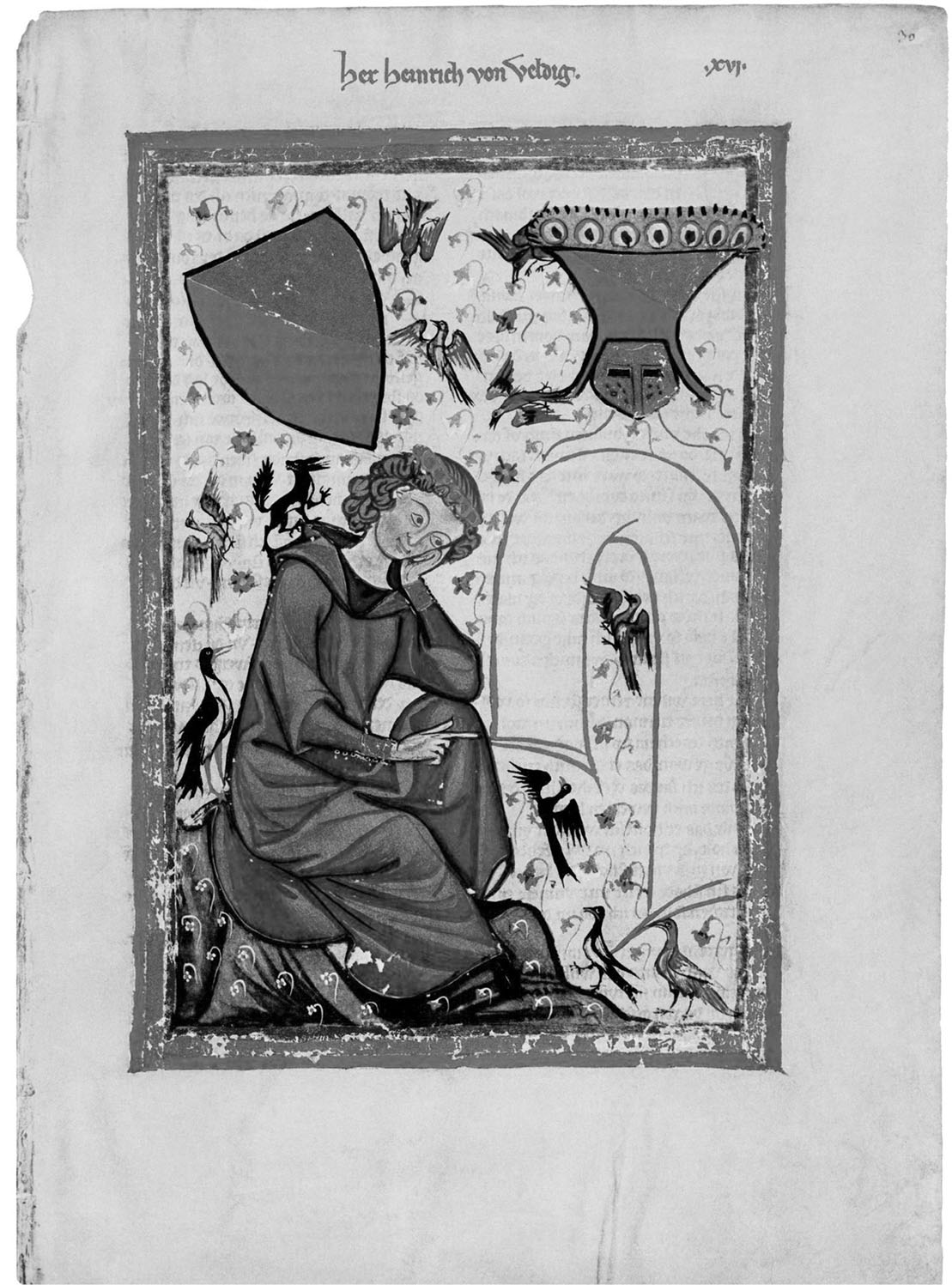

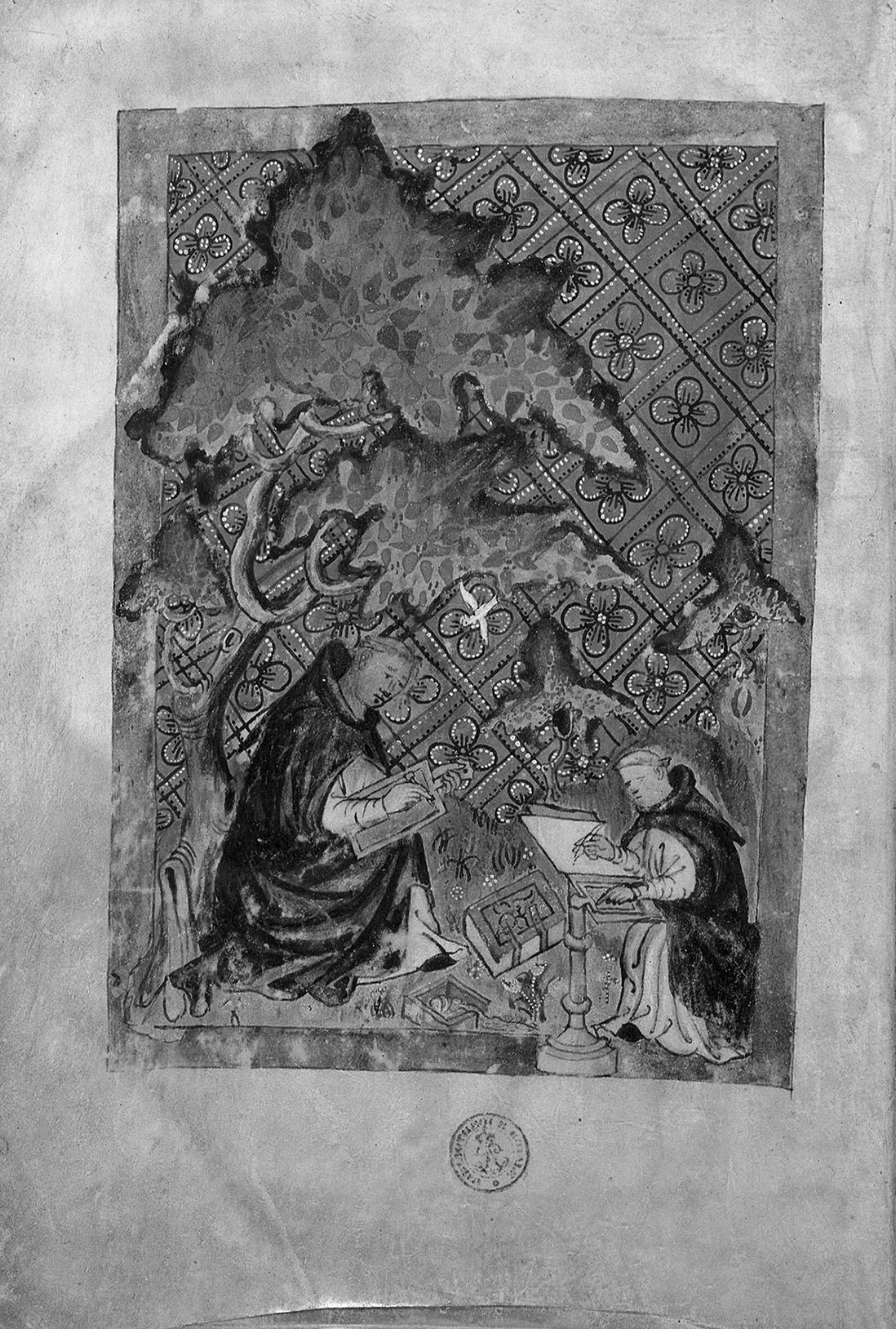

Hendrik van Veldeke as depicted in the Manesse manuscript.

Heidelberg, University Library.

There is nothing strange in Veldeke’s having been godfather to two traditions. He worked in the region watered by the Meuse and the Rhine, which was an influential and immensely prestigious region in the late twelfth century. Those primarily responsible for that prestige were powerful individuals and institutions that also acted as patrons to the poet Veldeke: men of authority in church and secular matters, with at their center, like a radiant sun, the Holy Roman Emperor himself. Recent research has shown Hendrik van Veldeke’s proximity to this focal point of political and cultural life. He had a demonstrable affinity with the literary scribes surrounding Frederick Barbarossa and his son Henry VI. He is known to have taken part in the glorious imperial festivities in Mainz in 1184, though it remains unclear in precisely whose retinue he served. He also attended another noble celebration: the wedding in 1174 of Margaret of Cleves and Ludwig of Thuringia, where his work in progress, the Eneid, was purloined, delaying its completion by several years. Besides this, he evidently maintained amicable ties with the prominent chapter of St. Servatius in Maastricht. It was from these circles that the commission arose for his life of St. Servatius, which reflected not only his great admiration for this vibrant bishop but also his imperial sympathies in disputes between pope and emperor. Did the poet and his clients in Maastricht perhaps have a dual motive in disseminating this work? Did they seek partly to propagate the veneration of St. Servatius and partly to curry favor with the Holy Roman Emperor, who was such a dominant physical and symbolic presence in this region?

Veldeke’s life and work show very clearly how closely the great literature of the “High” Middle Ages is bound up with commissions from high-ranking clients and how it bears their stamp. Even so, he displays considerable self-assurance in his writings; far from being the ventriloquist’s dummy of the great, he has a distinct voice, full of fervor. In his lyrical works, for instance, he dares to poke fun at certain conventions in the discourse of courtly love, overtly dismissing them as exaggerated and even redundant. He has no time for Tristan’s blind passion and refuses to see why he should give his life for his lady, however great his love for her. The closing lines of his poems, in particular, often have an ironic twist; but his entire collection of lyrics is suffused with a sparkle of joie de vivre (and joie d’écrire) redolent of iocunditas, the jocundity at the heart of the courtly ethics of the elite as it was crystallizing at the major courts of Europe. Great rulers set the tone, of course: Henry VI, for instance, like Guillaume of Aquitaine, would perform his own lyrics. But leading ladies at court must have been very influential, too. In Veldeke’s case, ladies, real and literary, certainly played a key role in his poetry. It was a lady who purloined his Eneid-in-progress, while another noblewoman, Agnes van Loon, co-commissioned his life of St. Servatius.

The elite culture of the twelfth century — and not just in France — developed precisely because of women’s interest in it, adding a dimension to life hitherto neglected by the macho male culture. Women often inspired highly educated scribes and secular clergy to compose literary works in the vernacular. Furthermore, the women in courtly circles often learned to read earlier and better than the men, and in some cases they even took to writing, thanks to their excellent education. Middle Dutch literature features an impressive example of a woman writer of European stature who was not only the first prominent writer and poet from the Medieval Dutch-speaking area after Veldeke but also the first writer of mystical love poetry in Western Europe: the Beguine nun Hadewych.

Hadewych

Strictly speaking, we know nothing about Hadewych. The dates of her birth and death are uncertain, as are the places where she lived and the circles she frequented. All our assumptions about such matters belong to the sphere of general conjecture. We can, however, paint a fairly plausible picture: Hadewych lived and wrote in Brabant, possibly near Antwerp, around 1240. She must have been of noble, or at least very prominent, birth, but by the time we encounter her as a writer she has renounced the fashionable world for the austere life of a Beguine nun.

The Beguine movement flourished in the Southern Netherlands of the thirteenth century. Beguines were found in France and Germany, too (though for some unknown reason not in England), but the epicenter of the shock the movement triggered within the church was in the provinces of Liège, Brabant, and Flanders. A host of women, dissatisfied with the well-trodden paths (and all the prohibition signs along the way) mapped out for them by the masculine authority of church and world, opted in mutual solidarity to strike out on their own. Setting up small communities in the towns, they tried to gain a modest subsistence with lowly handiwork, often glaringly at odds with their elite origins, and dedicated themselves wholeheartedly to the love of God, though not in any officially recognized convent structure. While they did not spurn all ties with the ecclesiastical world of men — confessors frequently visited the beguinages — their religious life and religious experience displayed for that time a remarkable degree of independence. As a result, the church treated the Beguine movement with suspicion, sometimes even tarring it with the brush of heresy. This certainly applied when certain Beguines started acting, in word and deed, as spiritual leaders in their own circle. Hadewych was evidently one such figure. While her work is composed in an entirely literary style, in an almost modern artistic sense, it should be interpreted primarily as a body of texts produced by a spiritual leader in an attempt to guide her fellow believers.

The beguinage in Kortrijk (Courtrai, West Flanders). Photograph: Wim Decreton.

This certainly applies to the Letters (Brieven) in Hadewych’s estate, thirty-one epistles to female friends about the pleasure, but most of all the pain, of life as a mystical lover, whereby she tried to give her readers the benefit of her own, similar, experience. Her Visions (Visioenen), fifteen descriptions of the mystic’s extraordinary experiences of the divine, are couched in an extremely difficult and sometimes near-impenetrable language, yet they are impressive in their attempts to touch the intangible and express the ineffable. But even here self-expression goes hand in hand with Hadewych’s role of counselor to her friends: the Visions, too, were written to teach and inspire.

Even the highly poetic Strophic Poems (Strofische gedichten) have an unmistakably didactic undertone. It took scholars some time to notice this, because of the distinctly literary quality and intensely personal testimony of these forty-five poems, and because the path of the mystic lover seems hyper-individualistic by definition. But however solitary Hadewych may sometimes feel here, whether or not by choice, we should not picture her as completely alone. Her poetry seems rather to be rooted in the desire to offer others a helping hand on the mystic’s path, a road that was incomparably arduous but correspondingly rewarding, and to gather an audience around her by sharing her own experiences. In forming this group, Hadewych naturally began with the Beguine community in which we may assume she lived; and if they were originally intended to be sung in the group, as recent research has persuasively argued, the Strophic Poems may have been more effective still as a cohesive force within that community.

But this context of a widespread movement and a close inner circle merely adds a little depth to our picture of Hadewych as a unique literary personality. It is scarcely conceivable that the hundreds of Beguines who lived at this time would have included many others who wrote as she did, although there is every reason to assume that her genius sprang from a larger source than currently available evidence suggests. Her highly developed literary language cannot have been a single bell ringing alone; it must have resounded with a rich linguistic environment, oral and written, literary and non-literary, all of it sadly undocumented. Other languages, too, undoubtedly shaped Hadewych’s idiom: first of all Latin, in which she was well-versed thanks to an excellent education, and which provided much of the imagery she worked into mystical texts and hymns; and her second “foster mother,” Old French, in which was rooted the courtly style of the secular love poetry that also clearly inspired Hadewych and that she elevated to the transcendental plane of mysticism.

Something else Hadewych shared with the literary style of courtly love poets, especially troubadours and trouvères, was her register-based poetics: the esthetics of the Strophic Poems is based on the principle of constantly varied repetition. In other words, the beauty of her verse arose not from originality writ large but from the artful manipulation of familiar conventions, with each poem couched in deliberate conformity to a familiar style while encompassing a new variation on it. Some have argued that Hadewych has too limited a vocabulary to be described as a great poet; but all the evidence suggests that this ostensible limitation was self-imposed, and that her variations on well-known themes, forms, and concepts not only highlight her virtuosity but, for the Beguine sisters to whom she primarily addressed them, also served as a kind of jargon, the intimate knowledge of which denoted both togetherness and exclusivity.

Learning to appreciate Hadewych requires us to read and listen to her frequently, as we can assume her fellow Beguines must have done. The more frequently we do so, the more intelligible becomes her work, which on first reading is so obscure, and the more unmistakable becomes her tone, which gives her a distinctiveness almost unparalleled in the European Middle Ages. Later generations, too, appear to have seen her as something of a phenomenon. Jan van Ruusbroec and his circle certainly did. Notwithstanding the distance in time, gender, and lifestyle that separated them from Hadewych, they recognized in her a kindred spirit, recording the Rithmata Haywigis de Antwerpia, thus preserving them for us. And unique she was, the mystical poet who went her own way in both religion and literature, and whose words about love still have the power to move us today — for instance in her seventh Vision, in which she describes how desire brings her to the brink of death and even (almost) beyond it: “[I felt] so violent and so frenetic, that I thought I would die of love-frenzy [orewoet, Hadewych’s word for mystical ecstasy] and, dying, would be in the throes of frenzy still.”

Allusions to perfect union with God in Hadewych’s oeuvre can be counted on the fingers of one hand; far more often she describes the desire for a union that cannot be achieved. But Hadewych shows that it is precisely in this tension between joy and sorrow and in the unconditional service of love for a Beloved who can never be wholly possessed that the quintessence and richness of love lies, so that total dedication remains the ultimate goal and signifies supreme happiness. The courtly-mystical opening lines of the first, programmatic, strophic poem put it like this:

Ay, even though it’s wintry cold,

The days so short, and long the nights,

Soon splendid summer will take hold,

From this most terrible of plights

Deliver us. That much becomes

Apparent now in this new year:

The hazelnut in finest blossom

Surely is a sign most clear.

Ay, vale, vale milies,

All of you, at this new time

Si dixero, non satis est,

Must needs rejoice in love sublime.3

Chivalric Tales in a Multilingual Context

While Hadewych was impressing upon her co-religionists the transcendental nature of true beauty, the elite circles from which many of the early Beguines came cherished an earthly “ideal of the sublime life,” as the great Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga aptly characterized the aspirations of the medieval aristocracy. And in the Low Countries, as in the surrounding countries, courtly culture appears to have been to a large extent a literary phenomenon.

Precisely when courtly culture crystallized and took hold in the Middle Dutch language area, and in which literary works, is shrouded in mystery and will probably remain so. Early Middle Dutch chivalric literature simply does not provide us with enough certainty to assign dates. For instance, it is far from certain that the chivalric epics centering on Charlemagne significantly predated those of King Arthur in these regions. It seems more probable that chansons de geste and Arthurian romances coexisted early on. The fact that both were cast in the same verse form — rhyming couplets, generally with four stressed syllables in each line — points in the same direction. However, we may be sure that a wide range of epics and romances in all sub-genres were known in the Middle Dutch, and more especially Flemish, regions. Both the material of Rome and that of Britain and France were available in a variety of forms.

It should be added that epics and romances in the French language were also widespread in the medieval Low Countries. Tellingly, in his Heroic Deeds of Alexander (Alexanders geesten), Jacob van Maerlant (of whom more later) seems to think nothing of citing epics written in both Middle Dutch and French. He evidently assumes that his readership is well-read, or more accurately, “well-heard,” in such literature in both languages. This is all the more noteworthy since Maerlant wrote primarily for the court of Holland, where French seems to have been used far less than in the southern Netherlands. In short, the literary life of aristocratic circles was a polyglot business.

Perhaps this is also why courtly love lyrics do not appear in Dutch until well into the thirteenth century. It seems very likely that courtly poetry in particular, which was then the most fashionable and primary musical genre in these circles, was best known in the Low Countries in French, in much the same way that English is the universal language of pop music today. It is significant also that Duke Henry III of Brabant (ruled 1248–61), who, like so many other high nobles of his age, was an amateur poet as well as a statesman and warrior, left us a corpus of love lyrics written in French. Lyrical verse, with its easily transported and relatively undemanding “physical condition,” was then without a doubt the most polyglot literary genre in the Low Countries.

But epics too were frequently written in French in these regions. This applies most notably, of course, to Hainault, where the surviving traces of literary life are dominated by French so thoroughly as to suggest that Middle Dutch may have had little more than marginal status as a cultural language. Contacts existed, however, between the nobles of Hainault and Holland, for instance, and the counties of Holland and Zeeland even came under Hainault’s authority in the first half of the fourteenth century. Traces of interest in French epics and romances have also been preserved in texts from Flanders and Brabant. For instance, one of the most famous manuscripts of the Lancelot en prose, the powerful, chronicle-like prose trilogy on the rise, heyday, and fall of King Arthur’s rule, is of Flemish origin: witness the style of the miniatures in the Yale University Library manuscript 229. It illustrates, quite literally, thanks to its wonderful illumination, that nobles from the Low Countries actively engaged with the international literary life of the times.

Be that as it may, we can surmise that these same Low Countries also produced a great many translations and adaptations of French chivalric literature. The Prose Lancelot, for instance, was translated into Middle Dutch at least three times between 1250 and 1300. This is remarkable considering the sheer volume of text, stretching to thousands of pages in a modern edition, and certainly says something about the familiarity of Middle Dutch readers with chivalric literature. Most noteworthy of all, two of these translations are in verse, which is unique among the European translations of the Prose Lancelot. One of the verse translations has come down to us in dozens of fragments, while only the latter half of the other trilogy has been preserved. Each of them must originally have run to over a hundred thousand lines. Assuming that the verse form was chosen to aid oral transmission, and since no more than a few thousand lines could ever have been recited in any one session, the Middle Dutch translations of the Lancelot en prose conjure up scenes of serials extending throughout the winter, with audiences huddled together evening after evening, spellbound by the tale of Lancelot. They learned of his youth in the care of the Lady of the Lake, and of his arrival at Arthur’s court, where he becomes the most prominent knight and the queen’s lover; of the Knights of the Round Table, embarking en masse on their quest for the Grail, in which the only one ultimately to succeed is Galahad, Lancelot’s son, the only knight whose flesh is pure; and of how Arthur’s kingdom eventually collapses, ripped apart by internal envy, hatred, and treachery.

But for whom were these translations of Old French epics and romances produced? This has long been a vexing question among scholars of Middle Dutch. The clearer it becomes that the elite of the Low Countries played a highly active role in Francophone culture, the likelier it seems that these translations were written for others, outside that elite. Perhaps they were for the burgher classes, who are known to have attained a comfortable standard of living early on in the southern Netherlands, in highly developed cities such as Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres, and who sought in this way to imitate the fashionable nobles. In that case, the situation would have resembled that in England. The English high aristocracy, too, thoroughly enjoyed and promoted French epics and romances, while the middle ranks of society preferred to read their literature in English. The counts of Flanders are likewise known to have granted far more commissions to French than to Middle Dutch poets, the most famous example being the one granted by Philip of Alsace in about 1185 to none other than Chrétien de Troyes for his Perceval.

It is perhaps no coincidence that of all works by Chrétien it should have been the Perceval that was translated into Middle Dutch: it was the only one produced for a client so far to the north. It seems likely that the Middle Dutch translation of this work, which appears to have been one of the earliest chivalric epics in the language, was intended for the burghers, who were subject to the count’s authority. They were by then no less wealthy than he, but they lagged behind in courtly culture. The fact that none of the extant manuscripts of Middle Dutch chivalric romances display the kind of luxurious finish typical of the finest specimens in French, a finish that is suggestive of princely patronage, might point in the same direction. Still, one might equally well expect rich parvenus to have followed the opposite trend, and indeed the most impressive of the book-loving burghers in the medieval Low Countries keen to imitate the nobles, Lodewijk van Gruuthuse (see below), ordered books whose sumptuousness was on a par with those of the king of France and the Duke of Burgundy.

In the absence of any hard evidence concerning the primary and secondary public who enjoyed Middle Dutch chivalric romances, all we can do is hypothesize. Current academic opinion holds that we must guard against an overly schematic interpretation which would consign all Middle Dutch translations of French epics and romances peremptorily to non-chivalric circles. When we try to imagine the setting for those regular winter-long gatherings for readings of the Middle Dutch translations of the Lancelot en prose, a nobleman’s great hall seems no less likely a venue than a burgher’s upstairs room. The above discussion showed how French and Middle Dutch literature intermingled; the same may well have applied to their audiences, so that in practice it was sometimes perhaps more a matter of chance than design whether a particular work was available in French or Middle Dutch. In the latter case the audience may well have been members of the lower nobility, who were so intertwined with the civil patriciate in the medieval Low Countries that any distinction between the culture of nobles and burghers seems rather artificial. When the translator and editor of Floire et Blancheflor writes in the prologue to his Floris ende Blancefloer that the book is intended for “those unable to understand Walloon” (den ghenen diet Walsche niet en connen), he is not necessarily thinking of a completely different environment. The added fact that his edition does not diverge from the spirit of the French original suggests a similar conclusion, and in this respect he is typical of the many translators who produced Middle Dutch versions of Old French courtly texts.

This episode of Dutch literary history thus illustrates the inspiring influence of French sources. French texts were not just read but translated, adapted, and sometimes rewritten. Occasionally something entirely new would appear in the genre, a new Arthurian romance spun with variations on the international matter. The finest of these new inventions was undoubtedly the Romance of Gawain (Roman van Walewein). In his prologue the poet says that he would have translated it from French had it existed in that language — but as the cards had been dealt differently, he wrote the story down himself. He thus creates the impression that he had in fact found the material in some form or other elsewhere and had not completely invented it, referring instead to a splendid Arthurian tale that he had upheven, “dug up.” Of course, the author might be playing with convention here, or using a gimmick to avoid presenting himself as an unreliable fantasist, but he did in fact find his material elsewhere. The Gawain is thought to derive from a fairy tale, and as such it is one of the finest European examples of the kinship between this genre and the Arthurian romance. It is the story that the Brothers Grimm call “The Golden Bird,” the earliest written version of which dates from the eighteenth century, though it evidently originates from the early Middle Ages, when it circulated orally, like all fairy tales.

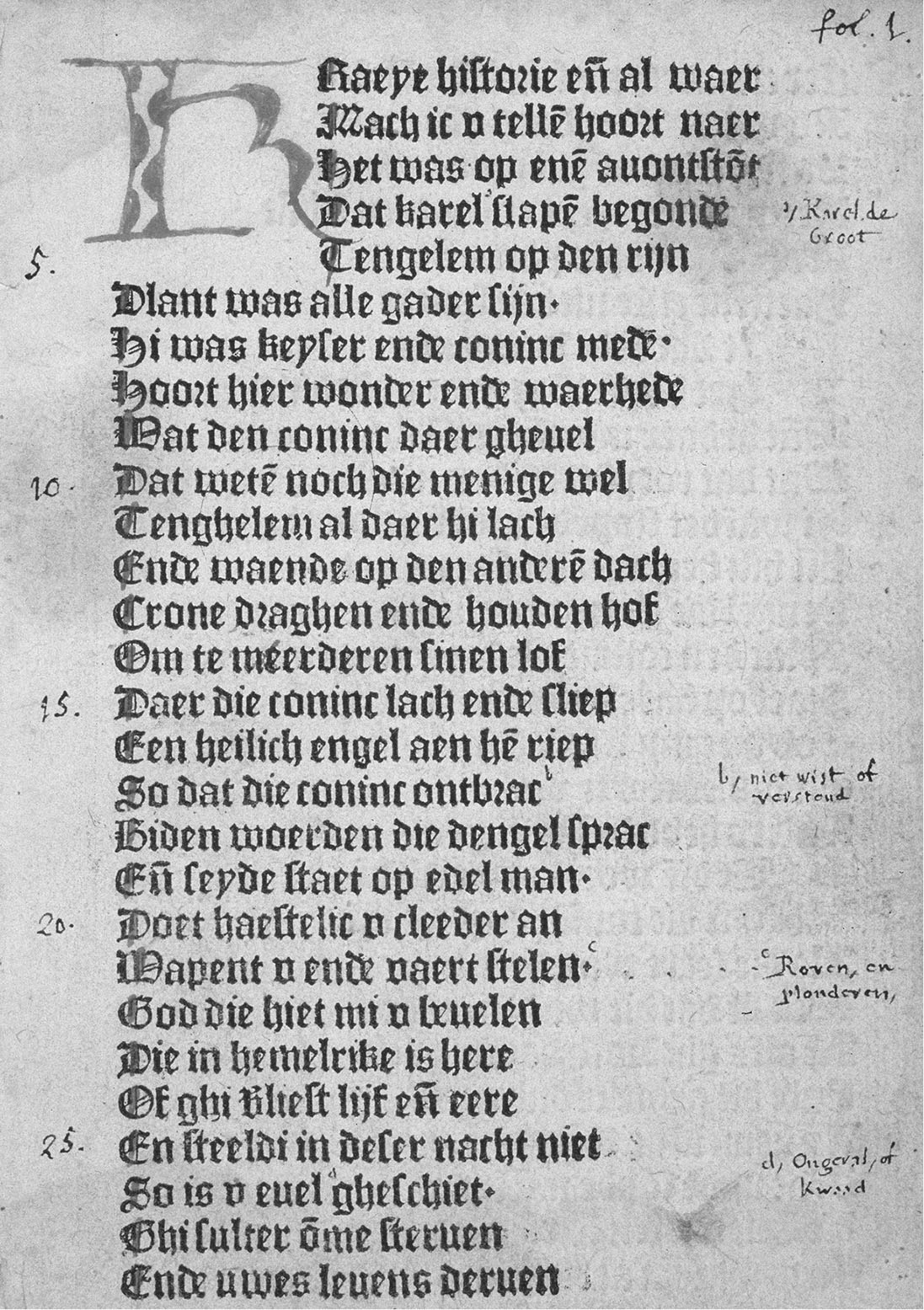

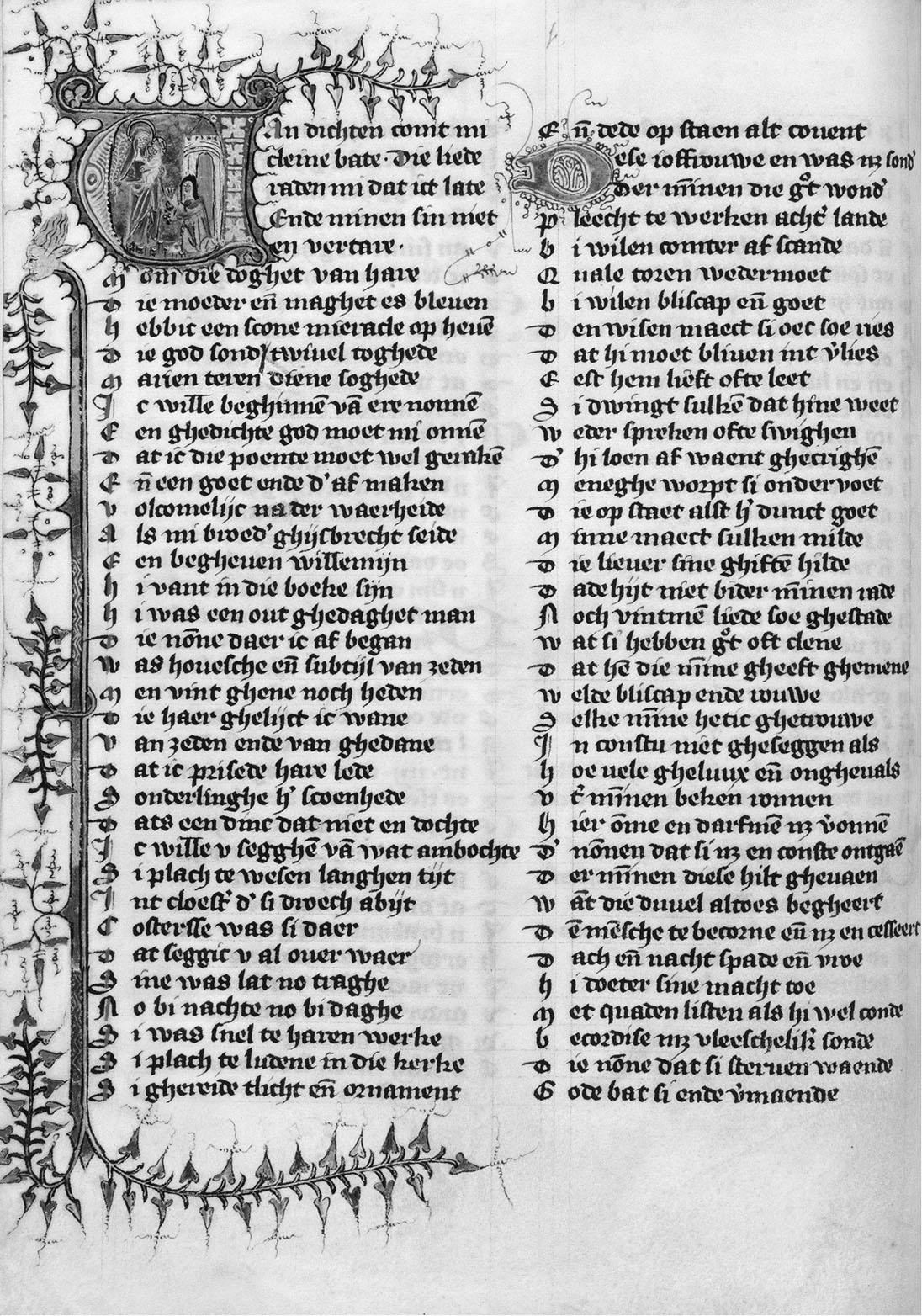

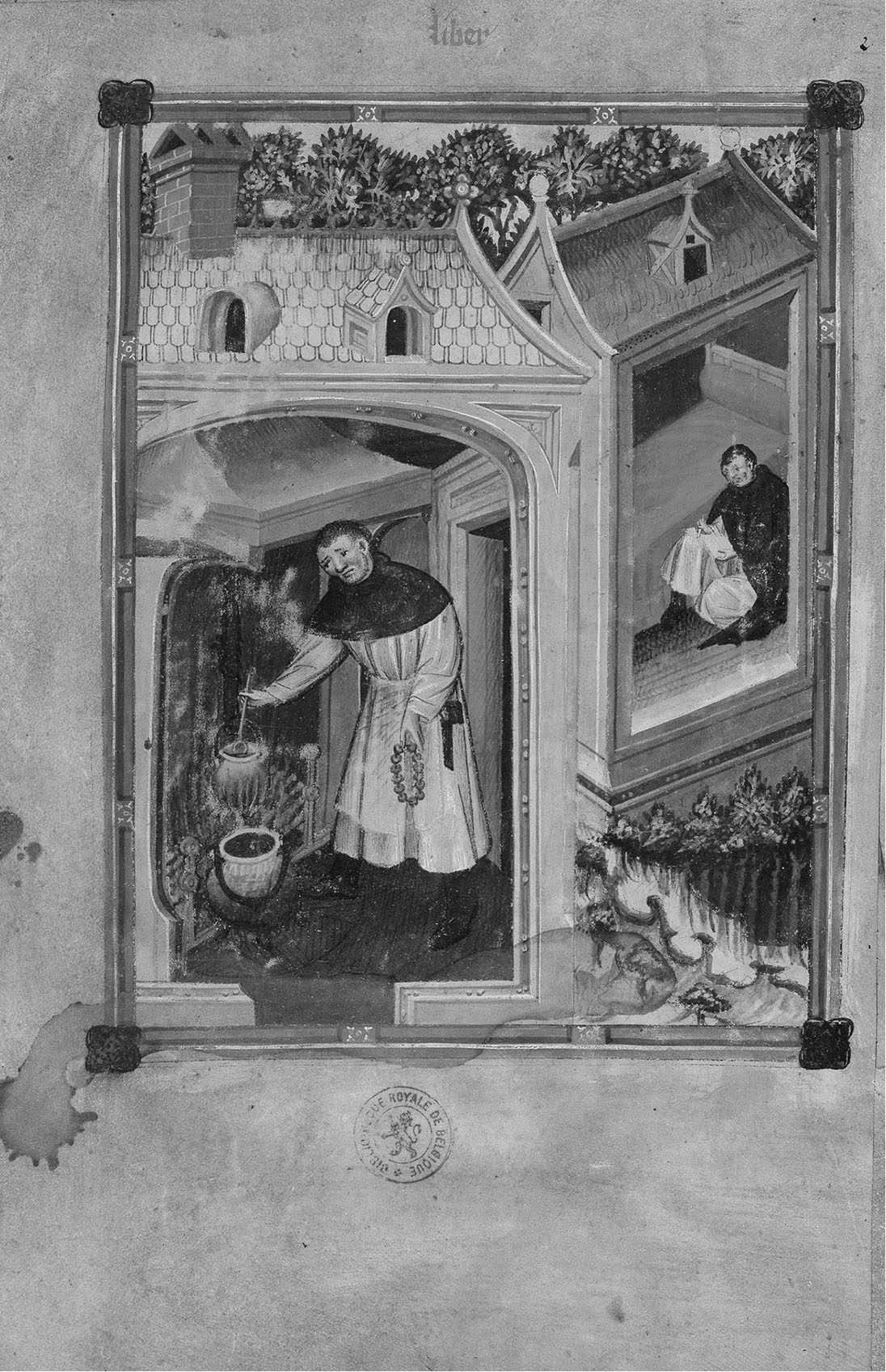

The beginning of Gawain and the Floating Chessboard (Walewein en het zwevende schaakbord). Leiden, University Library.

The Romance of Gawain tells the story of a staged quest. A young hero is dispatched to secure a highly desirable object. Having overcome numerous obstacles he eventually finds the owner, who is willing to relinquish the object provided the hero fetches something he himself covets. Having reached his second destination, the hero is dispatched to perform yet another daunting task. It goes without saying that he succeeds in the end and brings the original object of the quest safely home, stopping at each of the intermediate stages on the way. By the end he has also acquired a desirable young noblewoman, and he wins her hand together with fame and riches.

Since we have the Romance of Gawain only in medieval form, any speculation about how the poet dealt with his oral fairy-tale source is necessarily very tenuous. Even so, we sometimes glimpse traces of the fairy tale in the Arthurian novel, as in the peculiar figure that assists the hero on his difficult quest. This is the fox Roges, who proves to be an enchanted prince and whose original form is restored to him in recompense for his assistance. In Grimm, the object of the quest is a golden bird, but there are also variants, and the Gawain variant befits the medieval aristocratic setting. Here the story is set in motion by a magnificent chessboard which, like the Grail, though less sacred, floats in and out of the room, to the astonishment of all at Arthur’s court. But in the transition from fairy tale to novel the protagonist has undergone a far greater transformation. He is no longer the apparently inferior younger brother or some other underdog, as in the Grimms’ story, but none other than King Arthur’s right-hand man Gawain. The choice of Gawain as the protagonist actually gets the poet into difficulties. There is an irresolvable discrepancy between the stereotypical fairy-tale ending, in which the hero happily marries the princess he has acquired along the way, and Gawain’s profile within the Arthurian genre, as a proud bachelor who has plenty of romances, but with a different beauty each time. The poet of the Middle Dutch Gawain solves this problem by declaring that the matter is open to question: while some people insist that Gawain and Isabel married, he himself doubts it.

The Dutch Romance of Gawain is typical of the extent to which the medieval Arthurian romance, in the Low Countries as elsewhere, exemplifies what Hans Robert Jauss has called the plurale tantum experience: familiarity with only one such text is no knowledge at all, since the charm of the genre lies precisely in the coexistence of numerous texts, each of which draws on the same complex of materials, but with slight variations each time. In fact this could be seen as the epic equivalent of Hadewych’s register-based poetics, the continuous manipulation of conventions, variations on the repertoire of themes and motifs, both limited and inexhaustible at the same time.

Regardless of the many intrigues, an Arthurian romance requires a happy ending. Contemporary readers and listeners knew perfectly well that Arthur’s knights generally win their fights, that dwarfs and giants are generally malevolent, and that the Round Table’s heroes regularly beat off dragons but never a mad dog. But the true connoisseur is one who is able to discern and appreciate how each new story plays with the topoi in its own way and varies it within the given framework — and above all, how each of those heroes surrounding King Arthur is a magnificent individual and leaps to the king’s defense at all times, but that each also has his idiosyncrasies. This applies to the “newcomers” Fergus (Ferguut in Middle Dutch) and Perceval (Perchevael) as well as to veterans like the nefarious Lord Chamberlain Keye, the honorable Ywein, and the impressive Lancelot, who plays with fire in his affair with Queen Guinevere (Guenièvre). Even the three independent translations of the majestic Lancelot en prose cannot conceal the fact that neither Middle Dutch poets nor their audiences warmed to the eponymous hero Lancelot, let alone to Tristan, whose story appears to have had a very limited reception in Middle Dutch. Did the medieval Dutch literary world recoil somewhat from such blatantly adulterous heroes? But it is clear — from the sheer number of boys named after him, for one thing — that Walewein (Gauvain, Gawain) was the best-loved figure of King Arthur’s Round Table, and that rather than attracting the ironic treatment that is sometimes his lot in the French accounts, he is here clad in the armor of the fearless, blameless knight, a pillar of Arthur’s order.

Besides all these well-known figures from the Round Table, Middle Dutch poets also created new characters. One is the Knight with the Sleeve, who arrives at Arthur’s court as a foundling, but who crowns his exploits by winning a large tournament as well as a lady. Most strikingly, there is also the black knight Moriaen, begotten in remote Ethiopia by one of Arthur’s itinerant knights. When Moriaen comes to Britain, many are initially terrified by his dark skin. But as Walewein (there he is again!) recognizes from the outset, Moriaen’s jet-black face does not conceal the devil incarnate but a splendid knight, who grows into a staunch friend and ally of King Arthur’s circle. The virtuoso, and in a sense quite audacious, qualities of this romance will be appreciated all the more by readers familiar with the entire genre, which serves as a backdrop against which the individual story stands out in bold relief. Such is the world of the literary plurale tantum of the Arthurian romance. It is hardly surprising that so many direct and indirect lines of influence can be traced between Middle Dutch Arthurian romances: the genre possesses an intense degree of intertextuality.

Chansons de geste

And then to think that this compelling Arthurian panorama had a counterpart, in an equally imposing complex surrounding the great Charlemagne! The creative reception of the Carolingian genre in Middle Dutch literature followed much the same path as the Arthurian epic. Here too we find a wide range of translations, revisions, adaptations (the latter are more common than is the case with the Arthurian matter), and new stories. The most famous offshoot of this branch, the Chanson de Roland, seems to have been transplanted to Dutch soil quite early on. Textual criticism has shown that the copy of the Old French text lying on the Middle Dutch poet’s writing desk was close to the famous Version d’Oxford, but the Middle Dutch poet abandoned the archaic lyrical structure in laisses, stanzas with a single rhyming sound or assonance. Instead he produced rhyming couplets corresponding to the usual pattern of Middle Dutch declamatory epic verse. The striking laisses similaires that give the Chanson de Roland its unique rhythm — each climactic episode in the drama, such as Roland’s death, is repeated several times with slight variations in consecutive laisses — were condensed into a linear narrative. In content the Middle Dutch poet remains true to the French text, with the notable exception that the heroic protagonists, instead of li Franceis (the French), are now called die kerstenen (the Christians). In other words, on foreign soil the “national” French epic poem was elevated to the more universal and recognizable level of an epic relating to the whole of Christendom.

All in all, the Middle Dutch Song of Roland (Roelantslied), which retains this title out of loving respect for the old French original despite being anything but a song, was created at a writing desk. We should not imagine some poet who, having heard and committed to memory the famous story, set about emulating it in Middle Dutch, but a writer in the literal sense, with an Old French book on his lectern at which he toiled away to produce a rhyming version in his own language. Although this procedure seems to have been the general rule, it may not have applied in all cases, and complex hybrid forms are conceivable. Take the equally early Middle Dutch version of Renaut de Montauban (c. 1220), the marvelous story of the Four Sons of Aymon (Vier Heemskinderen). The poet is believed to have adapted the first part of the story from a book, but then he went his own way, possibly because his French manuscript was incomplete or lost and he had to rely on his memories of past recitations of the Renaut.

Different again is the case of the Lorreinen, the Middle Dutch counterpart of the Geste des Loherains. In Old French this is an extensive cycle of stories revolving around a feud between two families, the Loherains and the Bordelais. It is a powerful chivalric serial, in which successive scions of the families continue their hereditary enmity, producing a chain of feud, revenge, and counter-revenge stretching for generations. The oldest two parts of this cycle, the Garin and Gerbert, were turned into rhyming verse in Middle Dutch, probably by a Brabant poet from the first half of the thirteenth century. But then the history of this “deep-rooted enmity” (verwortelde nijt), as the text refers to its theme, took on a life of its own in Middle Dutch. By the end of the thirteenth century a vast sequel had been added to the Lorreinen, which did not derive from the Old French but continues the story in its own way. The perspective is clearly that of Brabant, inspired here by the feeling that, since the dukes of Brabant had once been lords of Lorraine, they could lay claim to the hereditary succession to Charlemagne, from which they felt they had been unjustly excluded. The resentment on this score appears to have greatly fueled interest in Charlemagne and the stories surrounding his grand dominion, especially in Brabant. But the Flemish counts too felt intimately connected to the great ruler to whom they owed their authority as counts. So did some of their counterparts in Holland — after all, the father of Floris V, Count William II, had been elected “king of the Germans” in Aachen in 1247, and some sources relate that the pope would even have crowned him Holy Roman Emperor in Rome, with Charles’s imperial crown, had William not died in the harsh winter of 1256 (his horse fell through the ice during a punitive expedition against the people of West Friesland, making him an easy prey for his enemies’ spears and swords). Thus all the medieval royal houses of the Low Countries felt some connection to Charlemagne. It was certainly an attractive idea to cultivate ties with the greatest ruler that Christendom had ever known.

Perhaps the most graceful jewel of the Middle Dutch Carolingian epic was also forged in the circle of a great lord who identified with Charlemagne. But this is not necessarily the case, since Charles and Elegast (Karel ende Elegast) can be heartily enjoyed outside any aristocratic or political context. It is the superb story of the emperor Charlemagne, who, at the peak of his power, is visited one night by an angel of God who tells him to go on a secret, solitary mission for the curious purpose of stealing.

In the dark forest, the emperor, traveling incognito, meets another knight on a thieving mission. It turns out to be Elegast, a duke wrongfully banished by Charles, and who has been thus compelled to provide for himself and his faithful followers. Together the real and the bogus thief break into the home of Charles’s towering paladin Eggeric, and the master thief that Elegast has by then become (so very different from his fumbling companion) discovers that Eggeric is planning an attack on the emperor. Shocked, the companions part, and the pseudo-thief makes the other pledge to present himself at Charles’s forthcoming open court. There, of course, the plot is revealed — and Elegast kills the traitor Eggeric in a judicial duel. He himself is wholly rehabilitated and is given Charles’s sister, Eggeric’s widow, as a wife. All’s well that ends well, then — thanks to the guiding hand of God, who sent the angel on its nocturnal errand and hence gave his vicar on earth the opportunity to see the mistake he had made by banishing Elegast, and to rectify it, while at the same time averting imminent disaster. The narrator’s epilogue elevates the story to the universal human plan of divine Providence: “So may God help us in our cares / and turn to the good all our affairs.”

Fifteenth-century edition of Charles and Elegast (Karel ende Elegast). The Hague, Royal Library.

All this is related in detail in scarcely more than 1,400 lines. In form, then, Charles and Elegast is actually more like a novella than a true chanson de geste, and it is probably partly thanks to that conciseness that the work has come to be known as the pinnacle of this genre in Middle Dutch. The main criterion for this distinction, of course, is the sheer strength of the story about the great king and the noble thief, and in particular the very appealing character of Elegast. He is a remarkable figure, with a curious mixture of feudal and magical qualities. On the one hand he is a duke, like Eggeric, and a man who excels in chivalric duels. But he is also a thief with magical powers, who can understand the language of animals (by which means he learns that none other than the emperor is near at hand) and who can place Eggeric’s entire castle under a sleeping spell to facilitate the burglary. In spite of this enchantment, Eggeric awakens when the master thief is about to purloin his magnificent saddle with silver bells from his bedchamber. The fortune attending this misfortune is that Elegast, concealed under Eggeric’s bed, overhears the exchange between husband and wife in which the evil Eggeric divulges his heinous plans (and gives her a nosebleed when she protests), so that the thief can warn the emperor.

Modern logic may not be the strongest point of Charles and Elegast, but the story has been admired ever since the thirteenth century. Of all medieval texts, it is the one read most frequently at Dutch and Flemish schools today. This appears to be continuing a tradition stretching right back to the Middle Ages: from the outset, Charles and Elegast appeared in more printed editions than any other chivalric romance. Even so, it did not always attract unqualified enthusiasm. The fourteenth-century scribe and critic Jan van Boendale (to whom we shall return later) was revolted by the improbable notion of Charlemagne gallivanting around as an occasional thief, an idea to which not a single chronicle lent credence, and he offered this withering rebuke: “We read that Charles did thieving go; but heed my words, for well I know, that Charles was never thief” (Men leest dat Kaerle voer stelen; ic segt U al zonder helen, Dat Kaerl noit en stal).

This quotation from Boendale, one of the earliest examples of what we might call Dutch literary criticism, demonstrates that the Middle Dutch chivalric romance was already one of the primary literary genres in its own day. And although it has survived in tatters — more fragments have been preserved than intact works — and we generally know little or nothing about the authors and audiences involved, there can be no doubt about the popularity of rhyming chivalric tales in the Dutch language area at this time. The genre’s standing is more than apparent from the opposition to it by stern men of letters like Jan van Boendale and, earlier and more caustic still, Jacob van Maerlant, to whom we shall return presently. Its powerful appeal is also demonstrated by some satirical animal fables, of which Middle Dutch has a splendid specimen in Reynard the Fox (Vanden vos Reynaerde).

Reynard the Fox

The basic premise of Reynard the Fox is rather like that of Charles and Elegast. This work too centers on a confrontation between a king and an outlaw. Here too we find a plot to oust the monarch from his throne: Reynard tells King Noble about Kriekeputte (“Cherry spring”), where the gold lies that is needed to entice accomplices to join in a coup to crown Bruno the bear. But the ending of Reynard the Fox is utterly different. The plot against the king turns out to have been concocted by the outlaw, who unlike Elegast is not yearning to be rehabilitated at court but constantly dupes the king and his retinue and eventually absconds, leaving the rule of law in a state of collapse. The court’s grand presumption is exposed for what it is, a thin veneer all too easily stripped away to reveal vanity and greed. The malicious cunning with which Reynard the fox exploits this weakness makes his tale into a biting satire of the aristocracy and its entire entourage, while its form — kin to the chivalric epic — also satirizes that class’s favorite literature. The chivalric Charles and Elegast, with all its quasi-historicity and ostensible realism, at best portrays an ideal, whereas the animal fable shows how the world of men works.

Reynard the Fox opens, like many a chivalric romance, on a day when the king is holding court. All the animals have responded to the summons to appear before King Noble the lion, who will dispense justice to them. Only Reynard the fox has stayed away, because he knows that he has a great deal to answer for and fears heavy punishment. The animals pour forth their grievances about Reynard, although it is clear from the defense submitted by Reynard’s cousin, Grimbeert the badger, that the plaintiffs are far from blameless themselves. But then in comes the sorrowful funeral procession of the cock Chanticleer, whose children were bitten to death by Reynard, in the very period when the King’s Peace had been proclaimed. King Noble decides to issue a summons against Reynard and sends his baron, Bruno the bear, to his castle. Reynard feigns willingness to accompany Bruno to the king’s court but confuses the messenger with a story about a surfeit of honey to be found at a neighboring farm. Having been lured into this trap, the king’s messenger finds himself set upon by a crowd of angry villagers and ends up trailing back to court nursing his injuries, without Reynard.

Noble then sends the shrewd tomcat Tibeert to fetch Reynard. But he meets with much the same fate as Bruno, his particular weakness being a craving for juicy mice in the minister’s shed. Not until the court’s third summons, when his kinsman Grimbeert takes on the messenger’s role, does Reynard finally agree to go to King Noble’s court, where preparations to hang the manifest villain are in full sway. But Reynard has devised one final, elaborate ruse. He succeeds in maneuvering his greatest enemies at Noble’s court, Bruno the bear and Ysengrin the wolf, to the gallows field, after which he spins Noble and his consort an incredible story about a treasure near Kriekeputte that, he says, his late father had planned to use to finance a coup that would depose Noble and place Bruno the bear on the throne. The masterful way in which Reynard exonerates himself while seemingly confessing guilt, and manages to shift the blame to his late father and to Bruno and Ysengrin, has the effect of radically transferring Noble’s sympathies; the King’s pure avarice for the vast treasure does the rest. He gives Reynard a letter of safe conduct for his avowed penitence and even decrees that a piece be cut from the skin of Ysengrin and his consort to make a pair of shoes for this pilgrimage. Reynard quickly disappears, accompanied by Noble’s servant Cuwaert the hare. When the latter’s bitten-off head is later sent back to the court, Noble realizes the terrible deception that has been practiced on him, but it is too late.

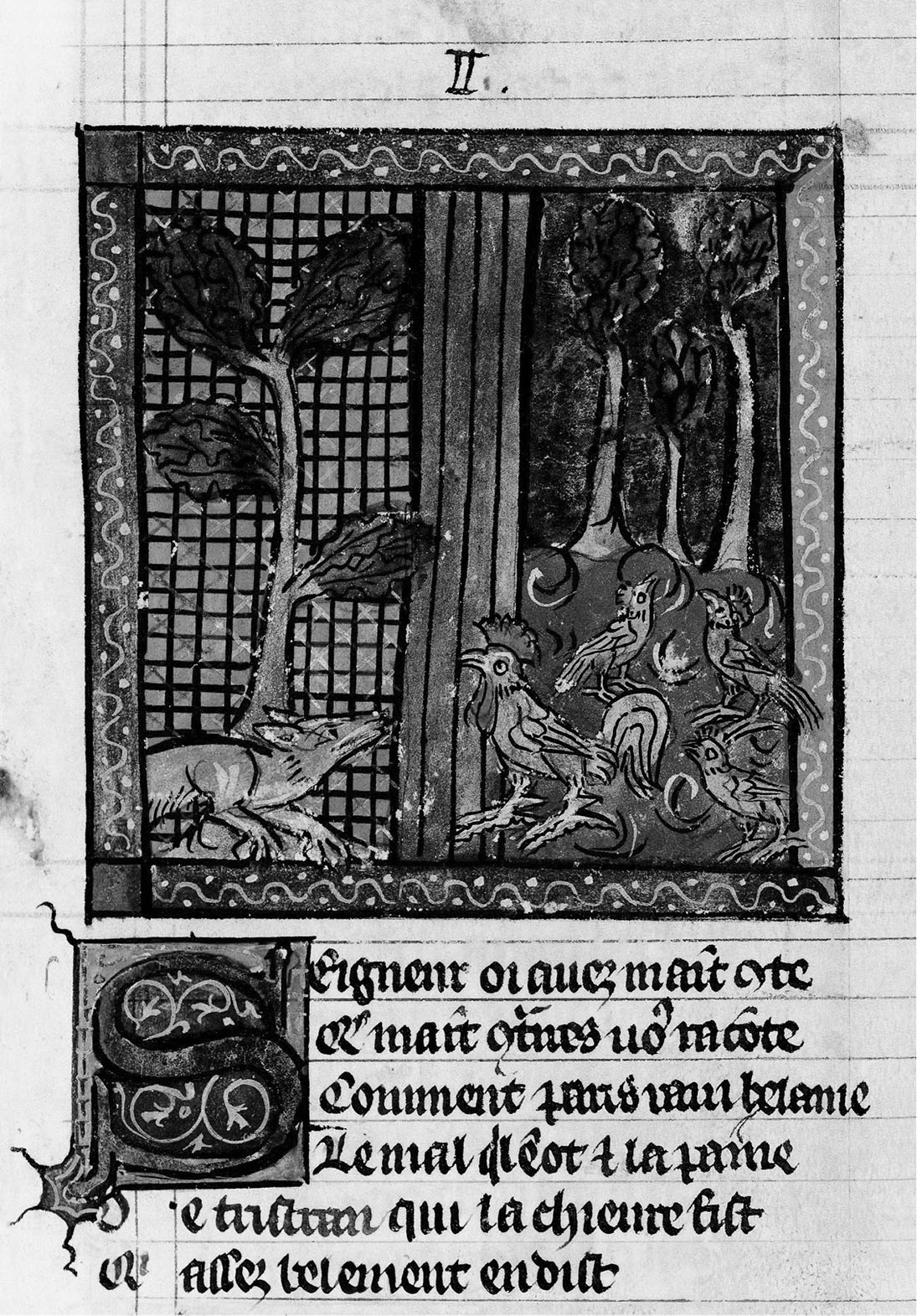

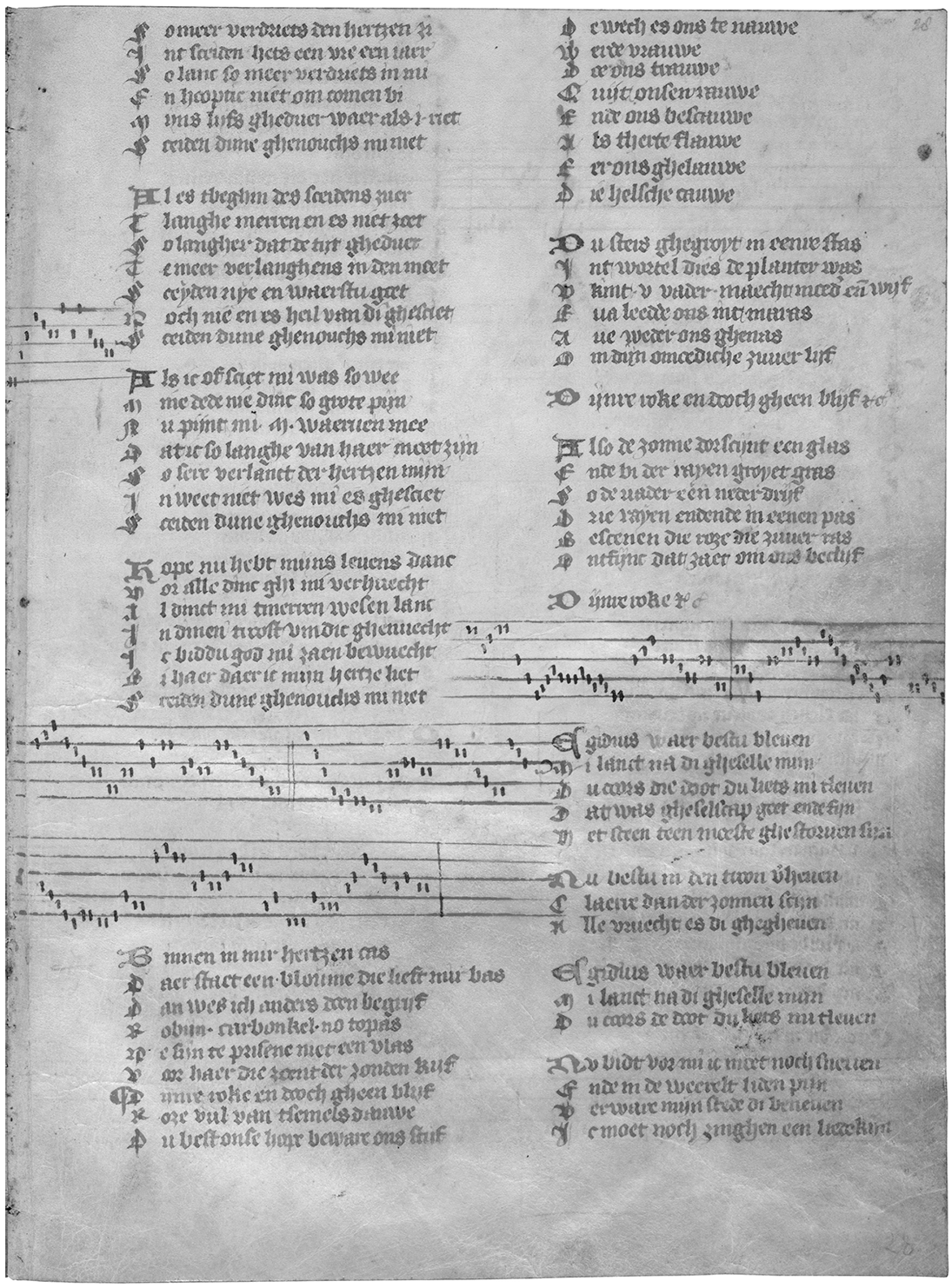

Opening miniature of a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Novel of Renart (Roman de Renart). Paris, National Library of France.

Reynard the Fox too was translated from the Old French. Several strands of the Roman de Renart served as the Middle Dutch poet’s source; in particular Le plaid, which deals with the case against the fox at Noble’s court. And like other Middle Dutch adaptors of Old French texts, this writer stays quite close to the original in the first part of the story and diverges from it altogether later on. But even in this respect he stands out from other authors. Reynard the Fox displays a remarkable unity, revealing itself as the work of an adapter who has complete control over the story from the outset and who, by using both minor and more radical devices, lends it a consistency that the Old French — which is, after all, a collection of strands rather than a romance in the true sense of the term — entirely lacks. For instance, the Middle Dutch adapter evidently took pleasure in having Reynard eliminate each of his opponents in turn, with similarly staged ruses. Both Bruno the bear and Tibeert the tomcat, and eventually even the king himself, are first flattered effusively by Reynard; in the course of this flattery the fox mentions quasi-nonchalantly a phrase that arouses intense desire (for honey, mice, and treasure, respectively), after which they forget their original assignment and allow themselves to be hoodwinked. A terrible reckoning ensues, at the end of which the malevolent Reynard publicly rubs his antagonists’ noses in their wretched defeat. The adaptive technique of Reynard the Fox displays a system and cohesiveness that is unique among Middle Dutch translations of French texts.

Reynard the Fox exhibits another, very striking, difference from both the French original and the work of other Middle Dutch adapters. Careful analysis of the discrepancies between Reynard and Renart has identified “conflict intensification” as the most significant feature of the adaptive technique. In Reynard the Fox the conflict between fox and lion is fiercer and grimmer, and the protagonist behaves with far more cruelty, while the king is vainer and more foolish than in the French text. This is all the more remarkable because it goes against the grain: most Middle Dutch poets tone down the emotions and extreme features of the French originals they adapt. Perhaps this increased intensity is also part of the reason why many regard this poem today as the greatest masterpiece of medieval Dutch literature, the prime text to read from this period and one that can be enjoyed without the need for complicated literary-historical explanations. As Joseph Bosworth, an Oxford professor who had previously worked as a minister in Rotterdam, commented on Reynard the Fox in 1836: “If it were the only interesting and valuable work existing in the Old Dutch, it alone would fully repay the trouble of learning that language.”

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that these unique qualities of Reynard the Fox were already well appreciated in the Middle Ages. The medieval sources that have come down to us are relatively numerous and are spread over a wide range in terms of time and region. A revised version of the Middle Dutch Reynard even reached the printing press, through the intermediate stage of Reynaerts historie, a reworking of the “old” text to which a fourteenth-century sequel was tagged on, relating the fox’s further adventures (that is, nasty tricks) in his battle with the court. The most striking testimony to the enthusiastic reception of Reynard the Fox in its own day, perhaps, is the fact that this Middle Dutch text was deemed worthy, in a reversal of the usual pattern, of a Latin edition. The Reynardus vulpes, whose date, around 1275, also provides a terminus ante quem for Reynard the Fox, is a lofty Latinized version of the tale of Reynard, in stylized meter, “the history of Reynard . . . known to many in Middle Dutch” (fabula Reynardi . . . agnita multis teutonice scripta); it was reprinted in Utrecht as late as 1473.

That the tale of Reynard the fox should have such power to enchant in the Dutch version must be ascribed to its author’s peerless genius. This makes it all the more regrettable that we know so little about him: only his forename, Willem, and the fact that he had previously written the Madoc, a work that most probably enjoyed a certain fame in its own day but not a snippet of which has survived. The Willem who produced Reynard the Fox must have written it in the thirteenth century, but whether he did so shortly after 1250 or somewhat earlier is uncertain. Regionally, he can be situated in Flanders, more specifically in the Ghent area. He may have been a secular priest, or perhaps a Cistercian. Whatever the case may be, he remains nothing more than a magnificent phantom.

Notwithstanding all these blanks, Willem’s mentality and intellectual qualities emerge quite clearly from the one masterpiece of his that has been preserved. They reveal a highly educated intellectual, extremely conversant with the world of law and order, and yet endowed with a sense of perspective (and harsh life experience?) that allowed him to view this world, and the world in general, through the eyes of an equanimous scoffer, who, having written his tale of Reynard the fox, vanishes from our sight just as unfathomably as Reynard himself vanishes from the sight of Noble’s courtiers at the end of the poem. Did the author draw the ultimate conclusion, perhaps, from his own poem? In this sense he seems the direct opposite of someone with whom he had much in common in terms of legal and linguistic education: that other great Middle Dutch writer from the thirteenth century, who was possibly a contemporary of Willem, from the same region, and who was certainly no less censorious of the world around him. This other figure, however, was a man who remained an idealist in spite of everything, who steadily continued to hold up mirrors to his readers, and who doggedly persisted, sometimes against his better judgment, in producing didactic work. His name was Jacob van Maerlant.

Jacob van Maerlant

Jacob van Maerlant’s fierce criticism of the glorious chivalric epic undermined his standing in Dutch literary history. He writes of Arthur’s farces (Arturs boerden) and Percival’s lies (die loghene van Perchevale), the taradiddle of love and battle (truffen van minne ende van stride) that one reads everywhere, epic tales of fabricated names and the never-born (ghevensde namen ende noit gheboren). He reserves his fiercest scorn for the French poets, who versify more than they know (die meer rimen dan si weten) and who murder true history (vraye historie vermorden) by smothering it in tall stories. The plethora of legends surrounding Charlemagne is the greatest thorn in his side, as if the truth about Charles were not quite eloquent enough; in this connection Maerlant reports reliable sources to the effect that Charles was eight feet tall and once hacked a Turk in half lengthwise, horse and all. In his eyes such accounts served as an antidote to the claims of certain infamous nonsense-writers (borderes) who tried to gull the literary public into believing that some of his paladins — Guillaume d’Orange, for instance — were even more excellent than the emperor himself. However, why those crazy Walloons called him Charlemagne baffled Maerlant altogether; it was surely common knowledge that his name was Charles the Great . . .?

If we characterize Maerlant in these terms, he comes across as a rather piteous figure with no understanding of literature. True, his blackout regarding the etymology of “Charlemagne” is just about the biggest blooper in his oeuvre, for this is a man who generally impresses us with his formidable knowledge and multilingual skills. In fact, Maerlant’s very erudition goes a long way toward explaining his rigor in dealing with chivalric literature. To someone of his intellectual background it was outrageous that accounts of awe-inspiring historical figures should have included such flagrant disregard for the historical truth as recorded in Latin writings, the only ones to enjoy authority among the learned.

To a large extent Maerlant’s works, and the mentality they convey, are the products of his intellectual education. We do not know the details of this training, however; indeed, the entire biography of the man who was in his day the most important writer in the Dutch-language area is veiled in mist. We can be fairly sure that Maerlant was born in Flanders, probably in the Bruges region, in about 1235. Though we do not know for certain that he attended the leading chapter school of St. Donatian in Bruges, he was definitely schooled in an illustrious center of intellectual life, given the wide-ranging knowledge displayed in even his earliest work. Most of his allusions draw on Latin sources belonging to the basic curriculum of elite schools. Virgil is woven into the fabric of his mind, he knows Ovid by heart, and he is completely at home in the vast encyclopedic Historia scolastica that Petrus Comestor composed around 1150 for the purposes of Bible study. Maerlant’s writings draw on over sixty sources in total — undoubtedly just a fraction of his reading. He could not have produced his work, at least not in this form, without that early schooling.

Such training may have been necessary, but it was not a sufficient condition for such a large output of writing in Dutch. That Maerlant should have gravitated to Dutch rather than remaining within the Latin world as so many of his fellow students must have done is closely bound up with the period he spent as a young man in Voorne, a small island in the North, on the border between the provinces of Holland and Zeeland. There he held the humble post of verger, besides which he is likely to have worked as a schoolmaster for children from affluent lay circles. Significantly, this was the circle surrounding the young Count Floris V of Holland, who was being prepared, under the supervision of his guardian Aleide of Hainault-Holland, to succeed his father, the Holy Roman king William II. Maerlant produced his first literary work with young Floris in mind. This was the long poem The Heroic Deeds of Alexander (Alexanders geesten). It relates the sparkling life of Alexander the Great, based on a Latin school epic and a great many related sources. In the context, there could have been no better choice of material than this inspiring story of a young ruler, one who also lost his father at a tender age but who nonetheless performed formidable deeds before pride triggered his fall — another equally good lesson for Floris’s future. Maerlant dedicated the work to the boy’s guardian Aleide, who seems to have had a decisive influence both on Floris’s education and on the awakening of Maerlant’s poetic aspirations.

The first fruits of Maerlant’s endeavors were evidently very well received at Voorne, as he obtained a series of new commissions over the years that followed. They were written in a similar vein, inasmuch as most of them focused on the leadership of young rulers and their place in history. Subjects include the young King Arthur, Torec, a young knight who rides out to restore the honor (and king’s title!) of his family, and the gargantuan history of the Trojan War, which Maerlant relates complete with prologue (the story of the Argonauts) and aftermath (the founding of Rome by Aeneas). Each one in turn was a didactic piece for the circle of the count-to-be, and when Floris was at length installed as ruler in 1266, at the age of twelve, Maerlant penned the poem Secret of Secrets (Heimelijkheid der heimelijkheden), taking as his source the Secretum secretorum, the mirror of princes that Aristotle had supposedly written for Alexander the Great.

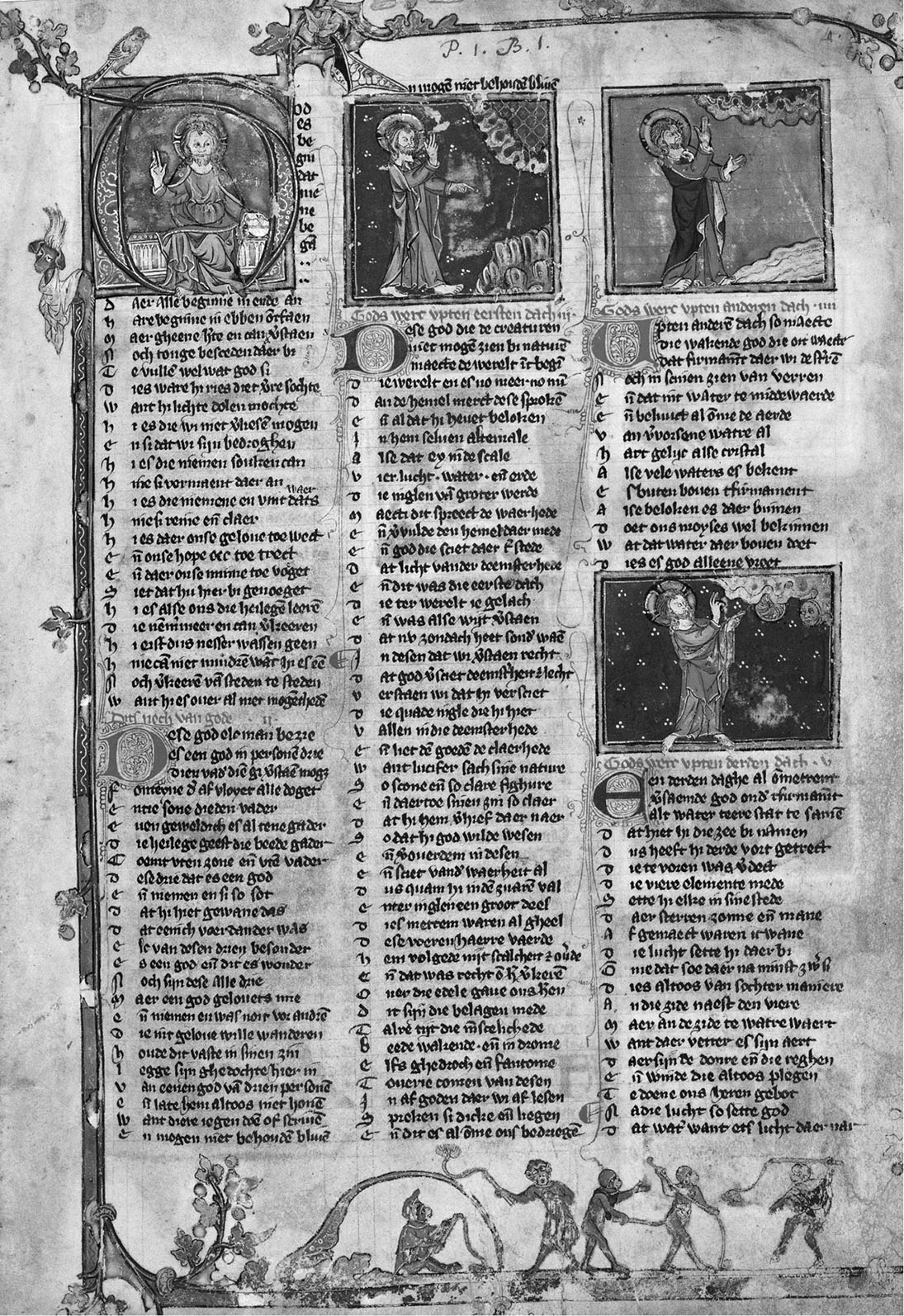

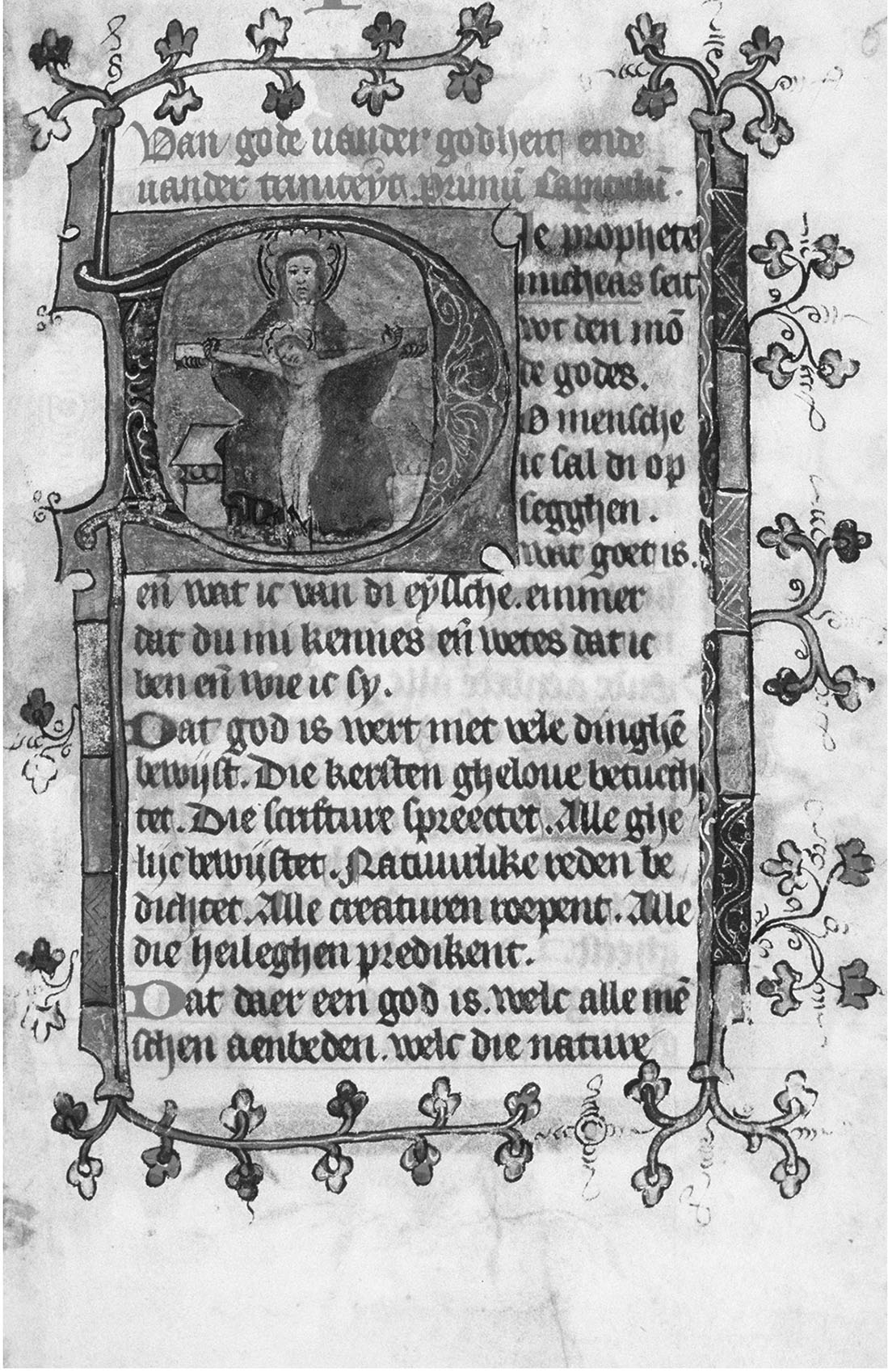

Jacob van Maerlant’s Mirror of History (Spiegel historiael) starts with the creation story. The Hague, Royal Library.

This would appear to have been the end of Maerlant’s immediate duties in Floris’s retinue. In any case, he returned to Flanders around that time. But he stayed in close contact with the northern nobles, and the works he wrote in his second, Flemish, period were also primarily dedicated to Count Floris and his closest followers. The best-known of these are his Best of Nature (Der naturen bloeme), a biological rhyming encyclopedia written for Count Floris’s young advisor Nicolaas van Cats, and the huge — over ninety thousand lines long — Mirror of History (Spiegel historiael), which Maerlant dedicated to “Count Floris, King William’s son” (grave Florens, coninc Willems sone), a complete rhyming history of the world from the creation up to and including the glorious first crusade.

In the same period Maerlant produced his Verse Bible (Rijmbijbel, 1271), a biblical history in over 35,000 lines, based on Petrus Comestor’s authoritative Historia scolastica. The Verse Bible is not a bible translation in the strict sense of the term, although Maerlant directly incorporated parts of the Vulgate into it. Even so, it appears to have brought the writer into conflict with the church authorities. In some sources this conflict assumes near-mythical proportions; according to one, the poet crossed the Alps for a meeting with the pope to account for his writings. While this was almost certainly a wild exaggeration, a good deal of evidence suggests that senior clerics did not take kindly to Maerlant. For all his erudition, he was probably no more than a cleric in lower order teaching lay readers the secrets of the Bible.

This anecdote makes it clear that Maerlant’s writing was not only at a crossroads but also within a field of tension between the church and the secular world. The tension was also palpable in a literary sense: that is, the writer had to strike a balance between scholarly material and precepts and his lay public’s more limited knowledge and needs. That he succeeded so brilliantly in this difficult balancing act probably explains the enduring success and popularity of Maerlant’s work. His vast output — ten major works, over 250,000 lines in all, plus a number of brief strophic poems — demonstrates a splendid fusion of the worlds of chivalry and clergy, and it was certainly the first such merger on this scale of any of the European vernacular languages. In many cases Maerlant was the first European to render the standard scholarly works of Latin, most of them from France, in the vernacular. His Mirror of History, for instance, was by far the earliest version in the vernacular of the Speculum historiale that Vincent of Beauvais had compiled for Louis IX.