4: Literature of the Enlightenment, 1700–1800

Marleen de Vries

I. Introduction

As the historian Jonathan Israel has shown, the early Enlightenment represents the single most significant revolution in culture and philosophy since the conversion of Western Europe to Christianity in the fourth century. The last quarter of the seventeenth century and the first quarter of the eighteenth saw the transformation of a traditional society and culture still hierarchical, theocratic, and agrarian into a community that was cosmopolitan, city-oriented, secular, commercial-industrial, and scientific. In this sense the early Enlightenment marks the transition from the premodern to the modern age.

The Enlightenment was not in fact a single coherent development but rather two rival movements. There was the moderate mainstream, which managed to reconcile old and new, science and Christianity, and there was the radical Enlightenment, which rejected any possibility of compromise and therefore had to be propagated in secret. Both movements had enormous faith in the future. The people of the eighteenth century coined the term “Enlightenment” because they were convinced that increased medical, scientific, and technical knowledge would lift the darkness of previous centuries. Progress heralded a new era of modernity, in which happiness would finally come within everyone’s reach.

The nerve center from which these radical, democratic, antimonarchical, anti-aristocratic, and anti-Christian ideas flowed was not Paris or London but the network of towns centered on Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Rotterdam in the northern Netherlands, the most prosperous region of Europe at the time and the busiest hub of European trade, shipping, high finance, and publishing. The Dutch Republic was the perfect breeding ground for modern ideas, enjoying as it did a strong cultural and intellectual tradition of tolerance, republicanism, and individual freedom. The power of the church, the crown, and the aristocracy had long been curtailed here, and there was a strong publishing trade.

Freethinkers in other countries recognized, with some envy, that a climate of tolerance had brought great wealth to the republic. The French theologian Noël Aubert de Versé (1645–1714), a fierce defender of religious freedom who lived in Amsterdam from 1679 to 1687, wrote exultantly: “Amsterdam owes its splendor and opulence, admired by all nations, to this precious liberty, because there is no nationality so foreign nor any sect so outlandish that its people cannot live in peace there, provided they are good people, sincere, loyal, and upright citizens.” The Irish deist John Toland (1670–1722), who was based in Leiden from 1692 to 1693 and lived and published in The Hague from 1708 to 1711, believed that “unlimited Liberty of Conscience” guaranteed Holland’s social and economic success.

Dam Square in Amsterdam with the Town Hall, the New Church and the Weigh House. Amsterdam, Municipal Archives.

Since the late sixteenth century, Dutch society had been characterized by a climate of — albeit relative — religious tolerance. Different denominations existed side by side, and any medium-sized village would have several churches. Although Calvinism was the approved religion and only members of the Dutch Reformed Church could be employed as civil servants, no more than 40% of the population was Calvinist. Roughly another 40% was Catholic, and the remaining 20% consisted of dissenters (Lutherans, Baptists, Remonstrants, Collegiates, and Quakers) as well as Jews and non-believers. In 1685, when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes that had granted the Huguenots freedom of worship, many French, Huguenot, and ex-Catholic intellectuals sought refuge in the Dutch Republic.

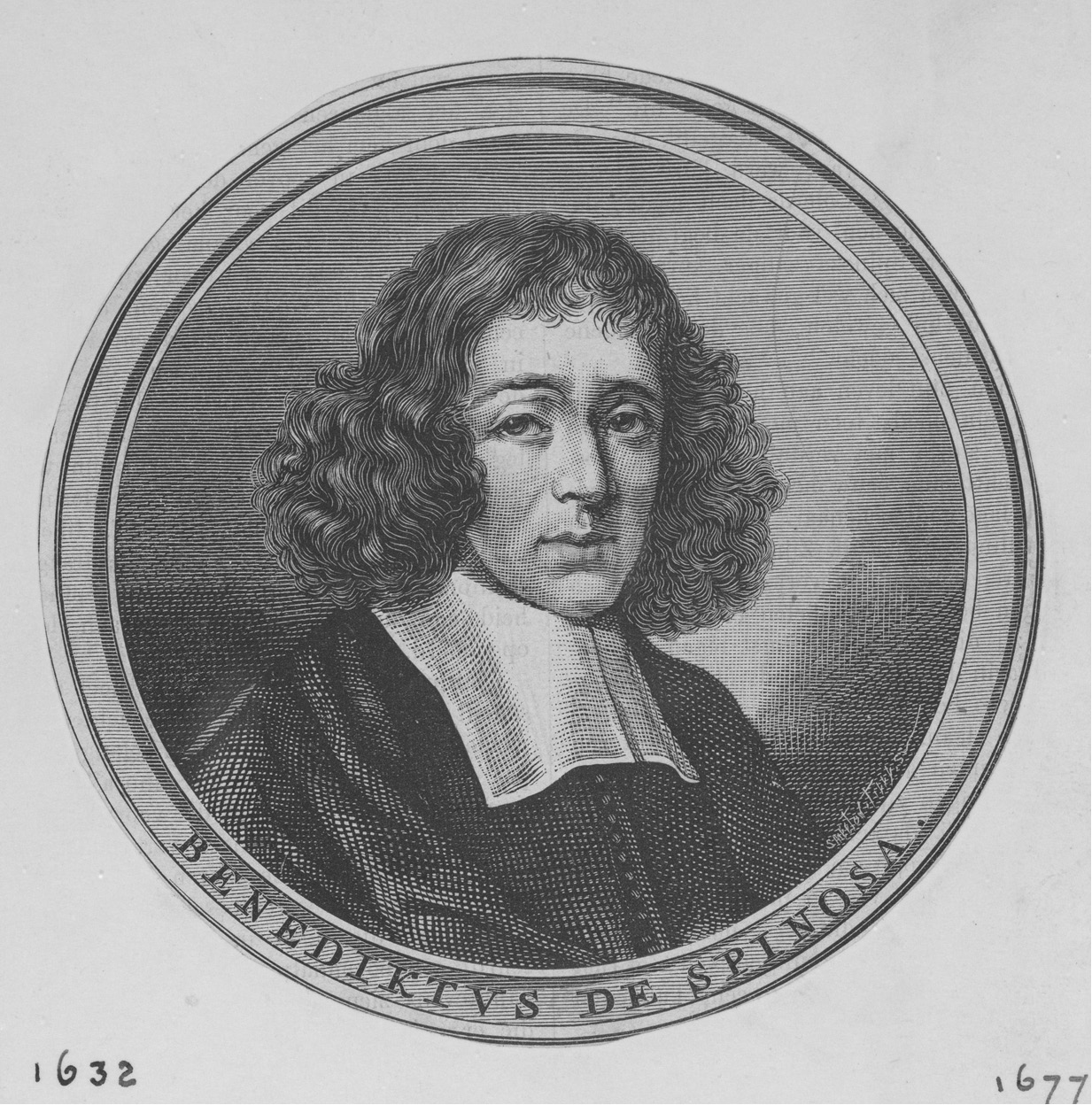

The Huguenot diaspora contributed hugely to keeping the republic at the center of the Enlightenment process. It was an important factor in the creation of a critical, heterodox press, mainly in Latin and French, which helped develop an entirely new publishing infrastructure well suited to the religious, political, and cultural climate. These presses constituted an independent, neutral, scientific republic of letters that flooded the rest of Europe with livres de Hollande. The principal founders of the new Enlightenment movement were Baruch de Spinoza (1632–77) and Pierre Bayle (1647–1706). Spinoza, the son of a Portuguese-Jewish merchant, was born in the republic. Bayle fled France for Rotterdam in 1681 to escape religious persecution.

Religious tolerance, indeed tolerance in general, was the subject of much intellectual controversy in the Enlightenment period. Philosophers analyzed the concept from their own perspective as rigorous skeptics, while ordinary citizens examined it as part of a quest for individual freedom, and merchants and publishers for commercial reasons. This freedom of expression was not absolute, particularly when it came to issues that were especially sensitive within the country itself; nevertheless, there was more leeway here than anywhere else, and Dutch publishers and printers exploited their relative freedom to the full. Works forbidden in neighboring countries were routinely published in the republic and smuggled out over the border. In the closing decades of the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth, this produced an extremely cosmopolitan intellectual environment.

John Locke found asylum in the republic under the assumed name of Dr. Van der Linden, and from 1683 to 1689 he belonged to a network of freethinkers, refugee intellectuals, and Enlightenment philosophers and theologians. Universities and colleges flourished as never before, attracting talented students from all over Europe. The professor of medicine Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738) taught Julien de La Mettrie and Albrecht von Haller. Voltaire attended lectures in Leiden by the physicist Willem Jacob ’s-Gravesande (1688–1742), one of the leading exponents of Newton’s ideas on the continent. The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) obtained his doctorate in Harderwijk and chose to publish most of his work in the republic. In Delft, on his own initiative and without being affiliated with any university, the civil servant and amateur biologist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) ground his own lenses and used them to conduct experiments. He invented the microscope and went on to achieve international fame with his studies of bacteria and spermatozoids. His research results were published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in London.

These and other scholars and amateur researchers published empirical studies that showed the world to be more fathomable, or at least less reliant on miracles, than previously assumed. They put “God’s miraculous works” into perspective, helping to erode the dominant position of the Christian faith. Literary works sometimes had a comparable effect. The University of Leiden had a reputation for exotic lectures on oriental cultures and religions, given by famous orientalists like the Schultens, father and son. Albert Schultens (1686–1750) found international fame with his translation of the Book of Job (1737), a work that showed Arabic, a language closely related to Hebrew, to be of use in interpreting the Old Testament. No less influential was Adrianus Relandus (1676–1718), who was based in Utrecht. His The Mohammedan Religion (De religione mohammedica, 1705), translated into Dutch in 1718 and subsequently into French, English, German, and Spanish, defended Islam, a religion usually described as cruel and tyrannical.

Until about 1720 the republic played a leading role in the propagation of European Enlightenment ideas. Then its prosperity gradually declined, along with its stability and its pioneering intellectual role, which passed to Britain and France. The rise of radical Enlightenment thinking coincided with a series of costly wars against Louis XIV. Stadtholder William III, who married Mary Stuart and became King of England in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was the greatest of all Louis’s opponents. It was the Spanish War of Succession (1702–13), however, that ultimately put paid to the supremacy of the Dutch Republic. The Peace of Utrecht in 1713 brought home the painful realization that the Republic was no longer a major political force: the peace terms were negotiated by Britain and France alone.

The death of William III in 1702 created a power vacuum that lasted until 1747. This period, known as the second stadtholderless era (the first one, from 1650 to 1672, occurred after the death of William II), had little effect on the way the republic functioned, since the political infrastructure was already decentralized and each of the seven provinces had sovereign status. However, it was the regents of Holland and merchants of Amsterdam who were best placed to take advantage of the situation and strengthen their own positions. The vast majority of the population gained little. When French troops marched into Flanders and Brabant in 1747, drawing the republic into the Austrian War of Succession (1740–48), the people rose and demanded change. They wanted a new Prince of Orange, hoping he might bring peace. Popular uprisings grew so fierce that the governing regent class had no choice but to appoint a new stadtholder. When William IV took over in 1747 the stadtholdership was declared hereditary, but both he and William V, who succeeded him in 1766, proved insufficiently decisive. The old anti-Orangist regent factions were simply replaced by regent factions siding with the House of Orange, so on balance little changed. The country was still governed by a small and powerful clique. Both stadtholders neglected the navy, which lost them the support of the merchants who depended on the fleet for their livelihood.

The Republic suffered economically as well. England and France grew into formidable competitors, and Amsterdam’s position as a staple market, retained for almost two centuries, effectively passed to rival markets like London and Hamburg. Many countries began to circumvent staple markets altogether by importing direct from producing countries. Family capital once devoted to trade was now invested in low-risk ventures — in bonds, or abroad — transforming the republic from a dynamic trading nation into a nation of shareholders. Floods and cattle plague did the rest. A large proportion of the population was unemployed and living in poverty, and the economic decline was reflected by that of the country’s two largest trading companies. The West India Company or WIC (Westindische Compagnie), established in 1621, folded in 1791. The United East Indies Company or VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), founded in 1602, ceased to trade a few years later in 1799, by which time the Republic’s extensive international trading network had shrunk to a relatively small colonial empire, and many of her overseas trading posts had passed to Britain.

By 1770 the consequences of economic decline were only too apparent. Although some individuals continued to enrich themselves, large numbers fell into poverty. “It is impossible for anyone who is at all sensitive or who has any feeling for his fatherland to walk through the inner cities without a tear in his eye,” wrote the Leiden lawyer and publisher Elie Luzac. James Boswell recorded that in Utrecht entire alleyways were crammed with wretches subsisting on potatoes, gin, tea, and coffee, while luxury reigned in The Hague and in the houses of rich Amsterdam merchants. Patience wore thin. Dissatisfied regents, wealthy merchants, and some outspoken citizens began raising their voices. The American War of Independence encouraged yet more opposition to the stadtholder, who was making no attempt whatsoever to protect Dutch commercial interests. In fact William V and his followers sided with trade rival England, while the Amsterdam merchants, their eyes on lucrative new markets, supported rebel British colonies in America by supplying them with weapons. The British threatened to seize Dutch merchant ships unless weapons shipments ceased. In 1780 the republic responded by joining the Armed Neutrality Pact between Russia, Denmark, and Sweden, an alliance created to defend freedom of trade, whose main target was the British navy. Britain reacted by declaring war on the republic. The Fourth English War had begun.

From this point on, Dutch society politicized rapidly. The longstanding divide widened between those campaigning for a republican form of government and the Orangists, who supported the stadtholder system. The republicans called themselves Patriots and prepared for civil war by setting up armed associations known as citizens’ militias. By 1787 their power as an armed force was such that several of their number had the audacity to detain William V’s wife, Wilhelmina of Prussia, near the small village of Goejanverwellesluis in the province of South Holland. Wilhelmina had been on her way to The Hague in the hope of influencing the course of the civil war. She was held captive for several hours and then forced to return to Nijmegen, where the stadtholder’s family had been living for its own safety since 1785. In retaliation Wilhelmina encouraged the Prussians to send an army of twenty-five thousand men, which successfully quashed the Patriot rebellion in late 1787. Many Patriots fled to France after William V restored his grip on power. The remainder set about organizing clandestine resistance in private homes, coffee houses, and clubs and institutions. It was not until 1795 that the Patriots, aided by French troops, finally seized control. William V fled to England, the Batavian Republic was founded, and there was a proclamation of “The Rights of Man and of Citizens” along American lines. All religions were declared equal in law; Catholics, Dissenters, and Jews were given permission to worship in public.

Meanwhile the southern Netherlands was struggling under the weight of its own rather dispiriting history. The River Scheldt was still blockaded and the country ruled by Spain. At the end of the Spanish War of Succession (1702–13) France’s Philip V de Bourbon retained the Spanish throne but lost control of the southern Netherlands, which now fell under Austro-Hungarian rule. The Peace of Utrecht in 1713 granted the Dutch Republic military guardianship over the southern Netherlands. This did not exactly make for good relations between North and South: “Holland only that is free, / And those who are nowhere so, are we,” wrote an angry Flemish poet. In the so-called “Generality Lands,” the buffer zone between North and South, where many Dutch soldiers were billeted, there must have been close contact, but the gulf between the two only continued to widen as France came to exert an increasing influence on the southern Netherlands. Austrian rule meant that French became the language of the court and of diplomacy. The status of French and of French culture in general grew enormously during this period, and French influence increased even further during the Austrian War of Succession. For four years, 1745–48, France directly occupied the southern Netherlands, and French generals introduced a French lifestyle, including French theater, literature, and fashion.

Not until after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 did the South enjoy better, more peaceful times. Empress Maria Theresa and Charles, Duke of Lorraine, modernized government structures and stimulated industry, mining, and trade. But Maria Theresa, universally praised as the “peacemaker,” died in 1780 and was succeeded by Emperor Joseph II, who made himself particularly unpopular by single-handedly imposing a series of reforms. This was the start of a revolutionary period in the southern provinces and the emergence of two resistance movements: the Statists, a conservative grouping led by Hendrik van der Noot (1731–1827), who aimed to preserve the privileges of the nobility, church leaders, magistrates, and local rulers; and the Vonckists, named after the lawyer Jan Frans Vonck (1743–92), who sought democratic reform. In 1789–90 the Brabant Revolution broke out. Although for a short time the democrats appeared to have gained the upper hand when they defeated an Austrian army at Turnhout, by the end of 1790 Austrian rule had been reasserted. In 1792 and 1794 French troops invaded and the southern Netherlands became part of France.

None of this violence seems to have had an adverse effect on cultural life, which flourished in both North and South. While a series of wars drained the state coffers and people went hungry, wealthier citizens ushered in a series of initiatives with far-reaching consequences. A political press emerged, created out of the need to combat a sense of crisis, convert Enlightenment ideas into action, and shape public opinion. Equally significant for the cultural infrastructure was the growing importance of the club. Since the seventeenth century there had been innumerable chambers of rhetoric in the South, whose self-declared aim was to cultivate the Dutch language and its literature. In the northern Netherlands the chambers of rhetoric were defunct, but here the concept of the club or association was revived in the second half of the eighteenth century. Within a decade or two there were hundreds of organizations regulated by their own laws and statutes. Fifty years sufficed to make this a “century of clubs,” with membership increasingly drawn from a broad public.

The Dutch Society of Sciences and Humanities (Hollandse Maatschappij der Wetenschappen), for example, founded in 1752, was a thoroughly learned institution, whereas the Society for Public Welfare (Maatschappij tot nut van ’t Algemeen), founded in 1784, was intended for ordinary citizens. The Economic Branch (Oeconomische Tak), a society established with the sole purpose of restoring economic prosperity, attracted three thousand members within a year of its founding in 1777. Cultural life existed largely within these institutions and was therefore shaped by them, whether they were Masonic lodges, learned societies, or literary clubs. They all had at least two things in common: their main purpose was the acquisition of knowledge, and the future of the nation was a standing item on the agenda.

By the second half of the eighteenth century the Dutch Enlightenment was largely a domestic concern, although the Dutch did continue to play a small role in propagating Enlightenment ideals across Europe. The Leiden bookseller Elie Luzac (1721–96) was appointed university publisher in Göttingen as late as 1753, but by then booksellers in the northern Netherlands were concentrating on the new domestic market, as they faced declining sales in the primarily French-language international book trade. Books for the Dutch market, still heavily influenced by the critical agenda of the Enlightenment, tested the limits of individual freedom, both freedom of religious and political conviction and freedom of expression. Theological dogmas came under fire, and various forms of natural religion began to replace them. The system of rank and privilege was attacked and egalitarian ideologies gained ground.

These late-Enlightenment debates took place against a background of economic decline, and participants regularly invoked notions of decay and doom. In France, Germany, and England the Enlightenment movement went hand in hand with increased international prestige, but the power of the Low Countries, North and South, was shrinking steadily. There was much speculation about the causes of economic collapse. The most popular explanation was a collective mental crisis: the people had grown feeble, effeminate, and infatuated with France, and somehow or other they had lost the morale and resolve characteristic of the old seventeenth-century fatherland.

We encounter this attitude time and again in the literature of the period, an astonishingly multifarious literature aimed at all sectors of society and written in three languages: Dutch, French, and Latin. French and Latin predominated in the southern Netherlands, where French Enlightenment ideas were consumed in the original French. The northern Netherlands developed a rich vernacular literature that gradually pushed Latin and French into the background. There was something to suit every taste, and it was in plentiful supply. Literary output doubled in a century. This was due at least in part to the rejuvenating force of the Enlightenment movement. Older genres such as dialogues with the dead, verse epistles, and imaginary travel stories were appropriated and adapted for a new era, and new genres came onto the market: encyclopedias, satirical journals, spectatorial magazines, epistolary novels, and plays written in prose. The literary landscape broadened rapidly to feature entirely new forms. There were even literary maps, such as that by Johannes Kinker in 1788, in which strenuous efforts were made to chart both the old and the new.

Above all, the literature of the Enlightenment was militant. It was intended to influence the way people thought in the hope of emancipating them. This helped to give eighteenth-century literature its chameleon character, as it adapted to changing political conditions and to the intellectual capacities of its intended readerships. The new literature was not only inventive: it might be called democratic, in the sense that it served all levels of society. Scholars, intellectuals, tradesmen, laborers, hacks, and a handful of writers from among the wealthier citizenry all contributed to it, keen as they were to unlock the truth and make the world more just and more humane.

Reflecting the struggle for political freedom, literature threw off a number of major constraints. French classicism, a literary current dominated by strict rules and a ban on religious and political subjects, inevitably fell by the wayside in this era of engagement. Slowly but steadily, classical genres such as the epic and the tragedy extricated themselves from classical rules concerning probability and decorum, the epic initially flourishing before dying an inglorious death at the end of the century. The rationalism of classical literature increasingly gave way to emotion. In the first half of the century, human passions and urges were still regarded with skepticism, but toward its close, emotions came to be valued as poetic and eventually as positive and creative powers. Horace’s concept of utile dulci was retained, as it could mean all things to all people. In fact “usefulness” became a key concept, particularly during the many debates on literary theory by clubs and societies. Elsewhere the entertainment value of literature took on increasing significance. Yet whether they were writing epistolary novels, poems for club anthologies, or sentimental literature, all writers, without exception, claimed that their work was intended as a contribution to the common good.

II. Early Enlightenment Literature, 1680–1725

The Radical Enlightenment

The radical Enlightenment, the intellectual revolution of the late seventeenth and the early decades of the eighteenth century, was first and foremost an attack on Judeo-Christian tradition and the social structures that flowed from it. Radical Enlightenment thinkers declined to submit to the power of the church. They did not believe in an all-powerful God or a social hierarchy determined by God, nor in the Devil, miracles, or reward and punishment in a life after death. Many of these radical thinkers lived and worked in the Republic, where they could write and have their works printed without too much interference. Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–51), for example, studied medicine in Leiden under Herman Boerhaave. His Man a Machine (L’homme machine, 1748), dedicated to Albrecht von Haller, another of Boerhaave’s students, was published in Leiden by Elie Luzac.

Such thinkers were often accused of Spinozism, a term referring not only to Spinoza’s ideas but to any philosophy regarded by orthodox Dutch Christians as tending towards atheism. Spinoza did of course go further than any philosopher before him. Born in Amsterdam in 1632, he was the author of Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670) and the posthumous Ethica (1677). While most philosophers, including Descartes, tried to reconcile their theories and insights with their Christian faith, Spinoza refused to submit to God or to any system based on theism. For Spinoza the divine was effectively synonymous with nature, and to study and understand nature there was no need for the Bible or clergy. Reason alone would suffice.

Baruch de Spinoza. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Spinoza gathered many disciples around him, some of them scholars, others ordinary citizens interested in philosophy. The Dutch translation of the Tractatus published under the title The Orthodox Theologian (Den rechtzinnigen Theologant) in 1693 carried his ideas to an even broader readership within the republic. The same decade saw the publication of The World Bewitched (De betoverde weereld, 1691–93) by the Amsterdam clergyman Balthasar Bekker (1634–98), in which Bekker maintained that witches and demons did not exist. The devil belonged to the realm of mythology too, he said, and he criticized the way the Bible had been translated into Dutch, claiming the official Dutch version, the States Bible (Statenbijbel) of 1637, contained more demonic passages than the original text. Bekker was sacked as a church minister, but his work was translated into English, French, and German; the German edition in particular provoked uproar.

Although the scientific revolution took place among a highly educated elite, it filtered through to a broad audience. While the new philosophical ideas had repercussions for literature, writers were experimenting with new literary forms. In fact, the final decades of the seventeenth century saw a remarkable parallel between the drive to experiment in philosophy and in literature. The need arose for literary genres that could accommodate thought experiments. Rather than the familiar classical genres like tragedy and the epic, which required authors to adhere to all kinds of rules, there was a move towards genres that were not, or not yet, codified and therefore allowed the writer considerable freedom: the farce, the novel, and poetry. These more trivial genres turned out to be the most appropriate vehicles for less than orthodox opinions. An anonymous farce called The Courtship of John the Cad and Kate the Bitch (De vryagie van Jan de Plug en Caat de Brakkin, c. 1691), for example, provides a defense of Balthasar Bekker’s ideas.

The novel proved to be a particularly stimulating genre. Out of nowhere, around 1680, the Dutch picaresque novel appeared, populated by scroungers, swindlers, adventurers, whores, and sex-crazed students. Titles like The Hague Libertine (De Haagsche lichtmis, 1679), The Leiden Street Ruffian (De Leidsche straatschender, 1679), The London Jilt, or, the Politick Whore (D’Openhertige juffrouw, 1680), Amsterdam Whoredom (’T Amsterdamsch hoerdom, 1681), The Dutch Rogue (Leven, op- en ondergang van den verdorven Koopman, 1682) and The Illustrious Deeds of Jan Dung (De doorluchtige daden van Jan Stront, 1684, 1696) speak for themselves. Jan Dung, especially the second volume, published in 1696, had the distinction of being the first pornographic novel ever written in Dutch. It did not travel beyond the border. The Dutch Rogue, on the other hand, was published in English as early as 1683. The London Jilt, or, the Politick Whore, published in English in 1683, proved cosmopolitan as well and was soon all the rage in both England and America; French and German translations followed. It tells the pseudo-autobiographical story of a prostitute, whose account of her survival tactics and techniques for relieving clients of their money, as she says herself, “does not have a great deal in common with the Ethics of Aristotle or however many other Ethics or works of Moral Philosophy the world may contain.”

But the “politick whore” also holds up a mirror to the reader, the suggestion being that society as a whole embraces morals that perpetuate deceit (and therefore prostitution). The fact that the unidentified author was probably a man is largely irrelevant as far as the narrative perspective goes. The author introduces a female narrator, describes the world in realistic terms, and is not afraid of psychological elaboration, so that The London Jilt, although of an entirely different caliber, stands comparison with Madame de La Fayette’s The Princess of Cleves (La Princesse de Clèves, 1678), generally regarded as the first modern European novel. Whereas the married Princess of Cleves is torn by internal conflict because of her overwhelming love for the young and elegant Duc de Nemours, the outspoken narrator of The London Jilt states baldly: “Because the things the little Misses generally try to make their menfolk believe, that they are not lustful and that, once married, they will never play the game of love unless they feel duty-bound to obey their husbands in that respect, I can assure you these are the greatest lies it is possible to conceive.”

Adventure novels like The London Jilt could hardly be described as radically enlightened in a philosophical sense. No dogmas were attacked in them, and they laid out no new philosophical systems. Nevertheless, their complete lack of morality lent them radical credentials, and they could certainly be described as shameless. There are no allusions to religious conscience or to a sense of guilt, quite astonishing in light of the overwhelmingly moralistic and religious literature of the period.

Only a decade later, in the 1690s, the time was ripe for the truly philosophical novel. The whore of The London Jilt pales beside real women of radical opinions. The writer Isabella de Moerloose (1660/61–after 1712) is one example. Born in Ghent in the southern Netherlands, she moved north to the province of Zeeland, where she married a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church. By 1699 she was running a small school near Amsterdam, where according to parish council records she taught the children “very godless and abominable things.” That same year she was locked up in a women’s prison. She is the author of the curious 670-page Peace Treatise, Come Down from Heaven through Women’s Seed (Vrede Tractaet, gegeven van den hemel door vrouwen zaet, 1695), an autobiography in which she describes all the ignorance she has encountered in her life. The book is packed with radical ideas. De Moerloose does not believe in miracles, nor in the holy Trinity, and she doubts that Christ was the son of God. She does not read, she tells us, or only very little; all her ideas stem from conversations in intellectual circles.

Just how wide such circles were we can only guess, but they must have existed. Hendrik Wyermars (c. 1685–after 1749), for example, a simple office clerk with no academic background of any kind, was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment in 1710, at the age of twenty-five, for writing a small Spinozist volume, The Imagined Chaos, and Supposed Sophistication of the Old and Contemporary Philosophers, Countered and Laid Aside (Den ingebeelde chaos, en gewaande werels-wording der oude, en hedendaagze wysgeeren, veridelt en weerlegt).

An anonymously published Spinozist roman à clef in two parts called The Life of Philopater (Het leven van Philopater, 1691 and 1697) affords us a glimpse into radical Enlightenment circles. It is an account of the intellectual and religious path taken by the central character, a theology student in Leiden, before he finally decides to convert to Spinozism. Philopater starts out as a sensitive Pietist, but he has difficulty with the awareness of sin this requires of him. The devil so terrifies him that he almost loses his mind. He is saved by a pastor from Zeeland, Johannes de Mey, who releases him from his fear of the devil. After De Mey’s death Philopater joins the Cocceians, a freethinking Calvinist sect whose beliefs were based not on dogma but on a covenant with humanity made by God. Dissatisfied with the sect’s view of the world, he falls for the charms of millenarianism in the form of Chiliasm, a sect using the Bible to decipher the date on which Christ will return to earth to establish a thousand-year kingdom of peace. Philopater “worked night and day, sought night and day, and time and again discovered new things, with which he was as inordinately pleased as if he had discovered the true Evangelical Pearl.” But a young adherent of the sect draws Philopater’s attention to the pointlessness of all this head-scratching over prophesy and imparts to him the principles of Spinozism.

Volume 2 of the novel, which had a print run of fifteen hundred copies, devotes a great deal of space to Spinoza’s ideas. This volume was immediately banned. Volume 1 was probably written by an Amsterdam schoolmaster called Johannes Duijkerius (c. 1662–1702), but volume two was attributed to its publisher, Aart Wolsgryn (active 1682–97). In 1698 Wolsgryn was fined four thousand guilders and sentenced to eight years in prison and twenty-five years’ exile from Holland and West-Friesland, one of the harshest punishments ever imposed for publishing a book. All unsold copies were publicly burned in Rotterdam.

The Emergence of the Periodical

The hunger for knowledge, truth, and the insights of the Enlightenment, which had created the demand for novels, produced another new literary genre, the periodical. Newspapers had existed since the beginning of the seventeenth century and had been joined in mid-century by newssheets or “mercuries,” named after Mercury, the messenger of the gods. Mercuries and newspapers did not try to shape public opinion but confined themselves to reports on trade, the fortunes of European aristocratic families, and matters of war and peace. News was primarily foreign news. Mercuries sometimes dressed up their information as literature, often, though not always, satire.

Learned journals created an intellectual revolution. They emerged in seventeenth-century France and England, but the first two titles, the Journal des Sçavants and the Royal Society of London’s Philosophical Transactions, both established in 1665, met with so much opposition from church and state that no similar publications appeared until the 1680s. Learned journals provided a platform for reviews of recently published scientific works (in fact largely extracts from them), summaries of the latest scientific debates, and scientists’ obituaries. Written in Latin or French, they amounted to an international forum for intellectuals and scholars — a novelty in western Europe, as it no longer took several years for a scholar to gather the latest scientific news from abroad. The subject matter of the new periodicals, which included the latest insights in theology, philosophy, and natural science, meant they were watched extremely closely by the authorities.

From 1684 onwards the Republic’s tolerant, enlightened climate enabled it to turn out more learned journals than any other country in Europe. It was here that News from the Republic of Letters (Nouvelles de la République des lettres, 1684–89) first appeared and rapidly grew into an influential journal. It was edited by the “philosopher of Rotterdam,” the freethinking scholar Pierre Bayle (1647–1706), who came to live in the republic in 1681 when Louis XIV closed down the Protestant academy in Sedan where Bayle was a lecturer in philosophy. In Rotterdam he became the first philosophy professor at the brand new Illustrious School, not a university but a college of higher education where students could take a foundation course only. News from the Republic of Letters was devoted entirely to the exchange of knowledge and aimed not only at scientists but at a general readership. Bayle introduced a new, bitingly critical style of reporting while always staunchly advocating tolerance and the application of reason.

A competing publication nevertheless proved even more successful: the Universal and Historical Library (Bibliothèque universelle et historique, 1686–93). This was a learned journal whose Genevan editor, Jean le Clerc (1657–1736), had chosen to live in the Netherlands since 1683 because of its tolerant climate. He expected to beat off all foreign competition simply by virtue of operating out of Holland, where he could get hold of any books he wanted and treat even the most sensitive subjects “because one is living in a country of freedom.” Contributors to the Universal and Historical Library included John Locke, who had spent several years in the republic, where he became a good friend of Le Clerc. Fourteen percent of the works discussed in the Library consisted of books published in Britain. Both Bayle’s News and Le Clerc’s Library were banned in France and other Catholic countries.

Title page of European Reading Room (Boekzaal van Europa). Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

The first learned journal published in Dutch did not appear until 1692. It was a bimonthly magazine called European Reading Room (Boekzaal van Europa, 1692–1702), edited by Pieter Rabus (1660–1702), deputy head of a Latin school in Rotterdam. Rabus hoped that publication in Dutch would make his magazine accessible to a non-scholarly as well as a scholarly readership. The journal continued after his death under the title Reading Room of the Learned World (Boekzaal der Geleerde Weereld).

Learned journals contributed to the Enlightenment movement in a number of ways. By highlighting the latest scientific findings, they helped shift the focus away from established authorities and the classics and toward everything that was new, innovative, and challenging. They spoke up for tolerance and intellectual objectivity and made their own contribution to both by publishing reviews that were deliberately non-partisan. They also showed there was no such thing as the truth: there were various truths, all in a constant state of flux. Learned journals helped the cause of the moderate, Christian Enlightenment by consistently trying to find a middle way.

Satirical magazines were the opposite of neutral and objective. Among the first was the Hague Mercury (Haegsche Mercurius, 1697–99), dedicated to “Lady Venus.” It was entirely the product of a lawyer in The Hague called Hendrik Doedijns (c. 1659–1700). At a breathtaking pace, in a relentlessly satirical style, Doedijns reported on a vast range of European affairs. The authors of previous newssheets had only presented bald facts, whereas Doedijns treated his audience to outspoken opinions about real people and events, in a style that was meant to entertain, because, as he put it, “A Mercury must be The Tomb of all Melancholy.” Doedijns broached thorny subjects with obvious relish: corruption at court, political abuses, Christian dogma. He made no secret of the fact that he was an ardent proponent of Cartesian methodical doubt, and in his defense of carnal pleasure he consciously posed as a libertine. Doedijns’s Enlightenment ideas provoked furious responses, published in a dozen pamphlets, and his magazine was banned in 1699. He died the following year, of unknown causes. Copies of the journal survived, and an updated reprint was published in 1735.

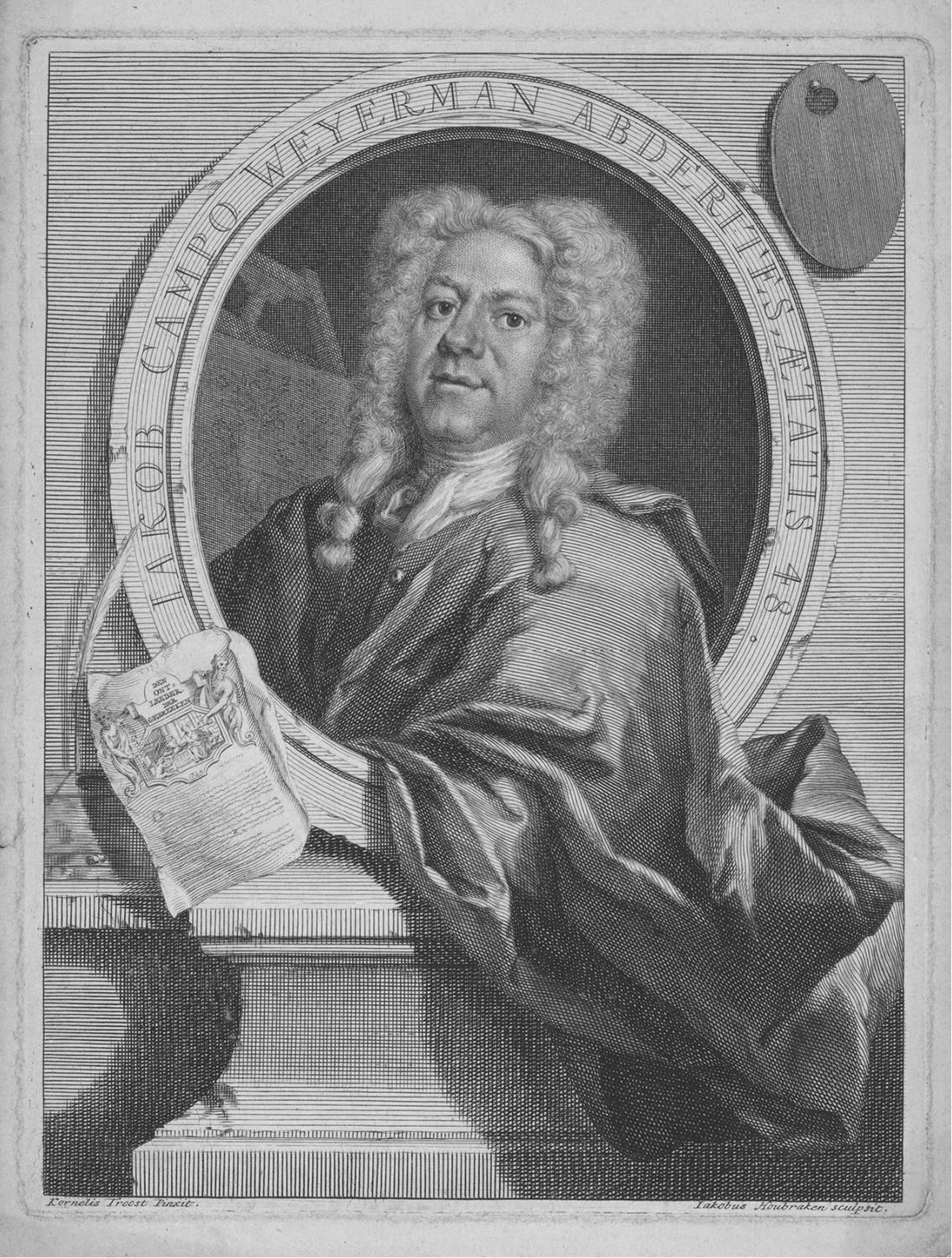

One enthusiastic admirer and follower of Doedijns was Jacob Campo Weyerman (1677–1747). It is hard to say which was the more adventurous, his life or his work. Weyerman initially trained as an artist and traveled the continent in that capacity. He found his way to the English court and toured Germany and France, and everywhere he went he met a remarkable array of highlife aristocrats and lowlife criminals, picking up some truly amazing stories along the way. At the age of forty-three he returned to the Netherlands, where he made his living as a journalist. Weyerman specialized in satirical weeklies, a risky enterprise since it was difficult to make satire pay, partly because there was so much competition. Hermanus van den Burg (1682–1752), author of the Amsterdam Argus (Amsterdamsche Argus, 1718–22), can hardly have been pleased to see the publication of Weyerman’s first magazine, The Rotterdam Hermes (De Rotterdamsche Hermes, 1720–21).

Portrait of Jacob Campo Weyerman by Cornelis Troost and Jakobus Houbraken. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Weyerman had a considerable talent as a writer, sufficient to captivate his readership for decades. Between 1721 and 1735 he published one weekly after another, with titles such as The Dissector of Deficiencies (Den Ontleeder der Gebreeken, 1723–25), The Echo of the World (Den Echo des Weerelds, 1725–27), and The Merry Disciplinarian (Den Vrolyke Tuchtheer, 1729–30). Alongside his journalistic output, Weyerman wrote several important historical reference works, including History of the Papacy (Historie des Pausdoms, 1725–28) and Biographies of the Dutch Painters (Levensbeschrijvingen der Nederlandsche Konstschilders en schilderessen, 1729–69), of which the fourth and final volume was published posthumously.

The key to Weyerman’s success lay in his modern and innovative prose, which seamlessly connected one subject to the next, drawing on a wealth of metaphors. Weyerman’s unashamedly individual approach must also have contributed to his popularity, as he presented himself in and through his work more forcefully than any writer before him. He dispensed entirely with the dictates of French classicism and combined poetry and prose to produce a stream of verse, fables, fairytales, anecdotes, advertisements, and narrative prose, fictional or otherwise. He had an extensive knowledge of contemporary European literature and often included pieces from foreign spectators and satirical magazines, such as The London Spy (although without acknowledging his sources). He was the first Dutchman to translate Swift, and in 1738 he became one of the first people ever to write about freemasonry. But mostly Weyerman wrote about his own country, describing a recognizable world in stories about real-life characters. As well as publishing satirical gossip, he imparted universal truths along the lines of “Wine tempers the natural coolness of the brain, which is why poets drink themselves to the inner door of the infirmary.”

Meanwhile a new type of periodical had arrived, known as the spectator. Imported from England, it quickly became immensely popular, since it was the first-ever vehicle for conveying opinions — although political discussion remained off-limits. The spectator introduced a new narrative perspective. Whereas the voice of the satirical magazines was that of a crotchety author, here readers were introduced to the fictional Mr. Spectator, a gentleman who produced entertaining prose essays with a moralistic streak. The tone was not usually satirical but one of enlightened pedagogy, and there were few of the references to famous people typical of satirical magazines. Sketches of characters and types were the main way of getting the moral message across, and Mr. Spectator made enthusiastic use of readers’ letters to illustrate his opinions, letters he may or may not have written himself. Spectators used accessible language and presented themselves as guardians of that new Enlightenment phenomenon called public opinion, articulating the moral standpoint of the average right-thinking, responsible citizen. Their authors could no longer be dismissed as hacks; some were highly educated people, including lawyers and quite a few preachers who had adopted the beliefs of Enlightenment Christianity.

Portrait of Justus van Effen by Des Angeles. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

The first Dutch spectators were written and published, in French, by Justus van Effen (1684–1735), the man who had introduced a continental readership to modern English literature in French translation. Like Weyerman, Van Effen struggled to make a living. Forced to break off his law studies when his father died, he had to make ends meet as a tutor, private secretary, translator, and journalist. In 1713 he joined the editorial board of the respected scholarly periodical the Literary Journal (Journal Littéraire, 1713–37), which enabled him to become a member of the Royal Society in London in 1715. Van Effen traveled to England and Sweden in his capacity as tutor and private secretary. In 1721 he published a French version of The Tale of the Tub (1704), Le conte du tonneau. It was followed by a French translation of Robinson Crusoe, published in three parts in 1720 and 1721, and Bernard de Mandeville’s Free Thoughts (1720), translated as Pensées libres sur la religion, l’église et le bonheur de la nation (1722).

Van Effen’s debut work had been a French-language spectator called The Misanthropist (Le Misanthrope, 1711). It was the first spectator published on the continent, and he followed it up with two similar magazines, The Bagatelle (La Bagatelle, 1718–19) and The New French Spectator (Le Nouveau Spectateur François, 1725–26). It was not until 20 August 1731, however, that Van Effen took the literary world by storm, when he switched to Dutch and began publishing the Dutch Spectator (Hollandsche Spectator, 1731–35).

The magazine was extremely successful right from the start, and there is no simple explanation for this. Van Effen was certainly an excellent writer, and part of his appeal must have been the way he used a fictional Mr. Spectator as a mouthpiece. For many readers, Van Effen’s dispassionate, lucid, paternal, and ironic prose was easier to digest than that of the boisterous enfant terrible Weyerman. Even more important, by around 1730 the economic decline of the republic had become visible and tangible, forcing people to think about their own sense of national identity, a task at which Van Effen excelled. This may also explain why he suddenly switched to Dutch, having published exclusively in French before starting his Dutch Spectator. Whether it was his own idea or whether the initiative came from his publisher, for purely commercial reasons, remains unclear. Van Effen died in 1735, so he did not publish in Dutch for long. We may never know the precise reasons for his decision, but his spectator set the tone for the next generation of magazine writers and for Dutch prose in general.

Lyric Poetry

The poetry of the early Enlightenment was written in three languages: Dutch, French, and Latin. Latin had the highest international status, since it enabled authors to engage with all other European countries. This was true of French to some extent, but certainly not Dutch. Many educated authors therefore chose to write poetry in Latin. Some were more successful than others, but Petrus Francius (1645–1704), Adrianus Relandus (1676–1718), and later in the century Petrus Burmannus Secundus (1713–78) gained widespread respect. The most famous Dutch Neo-Latinist of the period was Johan van Broekhuizen (1649–1707), not a scholar but a military man, famous across Europe and the first Dutch poet in history to be honored with a stone memorial. Van Broekhuizen, who wrote in both Latin and Dutch, excelled at occasional verse, a genre that was especially popular up to about 1760. His poetry in Dutch was published in Poems (Gedichten, 1677) and another collection with the same title that appeared posthumously in 1712.

Dutch and Latin vied to become the language of Dutch poetry, and around 1711 this led to a fierce literary debate known as the “Battle of the Poets” or the “Poets’ War,” a struggle that bears some resemblance to the “Querelle des anciens et des modernes” and the “Battle of the Books.” But while the French and English were ostensibly arguing about the extent of progress in all spheres, including literature, since the classics were written, the Dutch “Poets’ War” involved a number of different controversies and was largely concerned with the status of three kinds of literature: Neo-Latinist, French classical, and Dutch. At one time or another practically every well-known poet became involved in the argument, which initially arose from a difference of opinion between David van Hoogstraten and the Swiss émigré Jean le Clerc.

David van Hoogstraten (1658–1724) was deputy head of the Latin school in Amsterdam and wrote poetry in Dutch as well as Latin. Together with Pieter Rabus he published the anthology Exercises in Rhyme (Rymoeffeningen) in 1678. Another collection, Poems (Gedichten), appeared in 1697. Meanwhile he continued to study Latin poetry and to edit Latin works, including Aesop’s Fables. In his review of the Fables, Jean le Clerc railed against Neo-Latin poetry and called for poetry to be written in the vernacular. Van Hoogstraten hit back, calling Le Clerc a “French pixie, who, having washed up here penniless, has the audacity to enter into verbal disputes with all the most elevated minds of the region that feeds him, and then to curse them as pedants and pompous windbags.” The exchange marked the start of the Poets’ War. Le Clerc’s friends and pupils insisted it was old-fashioned and snobbish to go on writing poetry in Latin. Anyone with any love for his native tongue should write poems in Dutch, thereby enriching the language as Joost van den Vondel had done in the seventeenth century.

Further clashes ensued, this time about Vondel’s supposed greatness. This debate involved a completely different set of interlocutors. Those who identified with the Literary Journal, Justus van Effen being their most prominent spokesman, questioned Vondel’s stature as a poet and praised the simplicity of modern French literature with its French-classicist rules. They insisted that Corneille and Racine rather than Vondel should be seen as normative. Naturally, this prompted their opponents to speak up for Dutch literature and to criticize the many rules of French classicism. The Poets’ War did have one positive side-effect in that its many debates led readers, for the first time in history, to consider the Dutch literary canon very closely and to reflect on the value and identity of Dutch literature.

One of those who consistently sprang to the defense of Dutch literature was Jakob Zeeus (1686–1718), a painter, surveyor, and poet. Zeeus had a caustic way with words and excelled at writing satirical epigrams. In his debut collection, The Unblanketed World (De ongeblankette Waereld, 1706), which he subsequently dismissed as “the unripe fruit of my brain,” he lashed out at the hypocrisy of human society. The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing (De wolf in ’t schaepsvel, 1711), similarly motivated by a desire “to paint hypocrisy in living color,” was an attack on the church, superstition, and the priesthood. From 1712 to 1715 he contributed to the Poets’ War with poems like “The Decline of Dutch Poetry” and “The Lyric Mountain in Danger.” Although, as these titles suggest, Zeeus was far from satisfied with the state of contemporary poetry, his admiration for Vondel and for Hooft was boundless.

Hubert Korneliszoon Poot (1689–1733), the most famous Dutch poet of the first half of the eighteenth century, also joined the battle. Although a simple farmer from the village of Abtswoud in the province of South Holland, he became a living legend. Like Vondel, Poot was a self-made man. He studied Dutch and classical literature without any tutorial guidance and went on to prove that the privileged classes did not have a monopoly on poetic talent. Anyone, even a simple farmer, could be touched by literature:

And that I was the first Dutch boer

Of all my countrymen, tell now,

Who Song’s goddesses did win o’er

To join me here beside the plough.42

In “The Poets’ War” he expressed sadness about the literary quarrel:

So help me shackle discord, pray,

And bring no grounds for hatred hither,

For Poesy must bloom alway,

Nor may her noble praise e’er wither.

Portrait of Hubert Korneliszoon Poot by P. Velyn after T. van der Wilt. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Poot, whose talent emerged clearly from his first volume, Miscellaneous Poems (Mengeldichten, 1716), specialized in lyric verse rather than plays or epic poems. He was primarily a love poet and, like Van Broekhuizen before him, he showed great skill in capturing ordinary human emotions in lyrical language. Although he often alluded to classical mythology, he was equally capable of using a modern frame of reference to express the most intimate of emotions. Being a poet who, as he put it himself, stated “his opinion as it was, roundly and simply,” he wrote in a marvelously simple language and style. But it was his poetic sensibility, his self-expression, that guaranteed him lasting fame. He spoke “the language of his heart” and eighteenth-century readers opened their hearts to him:

Arisen at some early hour

Alone I see the fair moon ride.

Her light agleam on gable, tow’r,

She metes the blue with iv’ry stride,

And with her silver horns, serene and cold at heart,

She rends the dark apart.

Apart from the poets mentioned here, all of whom more or less conformed to commonly accepted poetic requirements and stayed within genre boundaries, there were various eccentrics. Most famous among them was Willem van Swaanenburg (1679–1728), a landscape painter, private tutor, and author of satirical weeklies and hermetic poetry. During his life Van Swaanenburg was an extremely controversial figure, and this quarrelsome reputation clung to him for the remainder of the century. On Johannes Kinker’s map of the literary landscape, published in 1788, the wayward poet is allocated his own Zwanenburg Island. The accompanying text describes the ghost of Van Swaanenburg, shouting and riding a double bass, in hot pursuit of the shade of Boileau. The image is not hard to interpret: out with French classicism! Instead of the ancient classical harp, Van Swaanenburg plays his own modern bass, forsaking the neat, credible, decorous, carefully tended garden of classicism in favor of a wild landscape dominated by the power of the imagination. The very first poem Van Swaanenburg presented to the public, in 1723, “Parnassus’s Rumble,” caused consternation among Dutch poets. Originally written to mark the wedding of a distant acquaintance of the author, its style was so exuberant it seemed as if the poet was unhinged, or at least prone to hallucinations:

That I might lift a Paradise upon my quill,

I built a bow’r of pearl and crystal; then your court

I clad in cedar planks to make an orange fort,

Through which Zephyr might drive fair Flora’s car at will.

I turned the ice to fire, set Summer skipping light

On ruby clogs beside a fleece of ivory,

Sent Aganippe treading over sand and sea

To wreathe you with her kisses in the whole world’s sight.

Aganippe, incidentally, is the nymph of a spring of the same name at the foot of Mount Parnassus; drinking from the spring gave poetic inspiration.

During the first half of the eighteenth century the intellectual and literary climate encouraged such experiments. There must have been a readership for this kind of poetry, because the same year saw the publication of In Praise of Gin (Lof der jenever, 1723) by Robert Hennebo (1685–1737) and the work of poets such as Hermanus van den Burg and Salomon van Rusting, who deliberately turned poetic decorum inside out. In the second half of the century, as literature increasingly became the domain of well-read, cultivated citizens, this type of humorous verse fell out of favor. Van Swaanenburg is mentioned in many subsequent treatises on literary theory, but only as a semi-psychopath, the epitome of the anti-poet, who must not be emulated.

Theater

During performances of Jan Vos’s Aran and Titus (Aran en Titus, 1641), the streets fell silent, or so Jacob Campo Weyerman writes in about 1730. He was no doubt exaggerating, but there was nothing more popular than a theatrical spectacle with plenty of blood and guts (eleven of the characters die in Vos’s play), a production that pulled out all the stops, with changes of décor, and special machines to produce wind and replicate waves. Audiences came to the theater for entertainment and to see and be seen. If the action on stage failed to enthrall them, they would peer into the private boxes, hoping to catch a glimpse of a couple kissing and cuddling. In both the northern and the southern Netherlands, going to the theater was a riotous affair. Eyewitness reports suggest drink flowed freely, accompanied by cracking of nuts, peeling of oranges, and audience participation in the form of wolf whistles and audible commentary.

For many years drama was not only the most entertaining and accessible literary medium but also the most important. In the winter months there were performances in the municipal theaters and in summer traveling theatrical companies put up tents at annual markets and fairs. More important, many citizens, especially the young, put on plays themselves. This was a particular feature of the southern Netherlands, where almost every town or village still had a chamber of rhetoric. Bruges had no less than three. Popular theaters were particularly successful during the final quarter of the eighteenth century, when the frequent theatrical contests might see the same play performed by twenty or more companies. The chambers were ideal venues for the cultivation of the Dutch language and for efforts to defend it against the powerful influence of French. This gave them a militant function both in the Dutch-speaking provinces of the southern Netherlands and in the Francophone part of Flanders. Plays written by seventeenth-century northern authors were most popular, although adaptations of classic French works were also performed. At every opportunity players flouted the rules of French classicism and put on plays that reveled in everything those rules condemned: religion, horror, and audiovisual spectacle.

Alongside the theater of rhetorical tradition were plays staged by pupils of Jesuit schools. These too strove to be as spectacular as possible, not only in order to entertain but also to make the Jesuit storylines, rendered in Latin, comprehensible to the audience. The Jesuit repertoire consisted largely of gruesome stories of Catholic martyrdom in which Christianity confronted paganism, one example being Christian Battle of the Holy and Glorious Martyr Sebastian, Roman Knight, Who Died for the Catholic Faith (Christelycken strydt van den heyligen en glorieusen martelaer Sebastiaen, Roomschen Ridder; Gestorven voor het Catholyck Gelove, 1743). No less heavily laced with torture and martyrdom were Saint Agatha (De Hl. Agatha) by Anton Flas (1650?–?), and two plays by a schoolmaster from Veurne called Jacob de Ridder (1728–ca.1783), Saint Quentin (De Hl. Quintinus, 1751) and Saint Barbara (De Hl. Barbara, 1780).

Municipal theaters were established relatively late in the southern Netherlands. Antwerp had a public theater on its main market square as early as 1660, but the Grand Théâtre on Munt Square in Brussels did not open until 1700; Ghent opened its municipal theater seven years later. At first only ballet, Italian opera, and French plays, usually in the Baroque style, were performed in Brussels. Ignaz Vitzthumb, an Austrian who became director of the Munt Square theater in 1772, managed to stage performances in Dutch, but not before the final quarter of the eighteenth century. Until then, private theater groups called “Compagnies” closely guarded their monopoly on Dutch-language plays.

The theatrical repertoire of the municipal theaters of the southern Netherlands was a mixture of Jesuit drama and adaptations of both French plays and works from the northern Netherlands. The most famous and productive poet writing for the Brussels stage, Jan Frans Cammaert (1699–1780), specialized in adapting classical plays to produce something known as “total Baroque theater.” He translated, rewrote, or adapted into verse some eighty tragedies, farces, and comedies originally in French, Latin, or Dutch. He updated Vondel’s tragedies Samson (Samson of heilige wraak, 1660) and Solomon (Salomon, 1648) and staged the same author’s Adam in Exile (Adam in Ballingschap, 1664) in Brussels a hundred years before it was first performed in the northern Netherlands. Cammaert produced only a single original work, the tragedy Punishment and Death of Balthasar (Straf ende dood van Balthassar, 1749). When rewriting plays he would always adjust them to popular taste, which meant adding plenty of spectacle, singing, and ballet.

Jan Frans Cammaert. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Francis de la Fontaine (1672–1767) is primarily known for his Discourse on Oration, of Service to Preachers, Rhetoricians, Actors and Associations (Verhandeling over de Redenvoering, dienstig voor Predikanten, Redenaers, Tooneelspeelers en Geselschappen, 1751). It is one of the earliest theoretical discourses on the art of rhetoric in the South and includes a brief history of the theater. De la Fontaine advocates a modern style of acting, with an emphasis on naturalness and simplicity. He was modern too in his love of Voltaire, becoming the first translator of Voltaire’s work in the southern Netherlands. His Alzire, or the Americans (D’Amerikanen oft Alzire, 1739) was performed only three years after publication of the French original. Like Cammaert, De la Fontaine left only a single original tragedy, The Variable Fortunes of Garibaldus and Dagobertus (Het veranderlyk geval in Garibaldus en Dagobertus), not printed until 1739 but first performed in 1716. Another well-known author of theatrical spectacles was Johan Laurens Krafft (1694–1768), born in Brussels and writing in both French and Dutch, who produced plays bursting with action and passion. His Iphigeny or Orestes and Pylades (Iphigenie ofte Orestes en Pilades, 1722) is certainly not a classical drama but a passionate work full of love, heroism, and valiant women. Similarly action-packed was his Hildegard, Queen of Norway (Ildegerte, Koninginne van Norwegen, 1727).

Theater in the northern Netherlands was considerably less robust. Although theatrical companies had replaced the old chambers of rhetoric, these existed only in the major towns. Municipal theaters were similarly scarce; in fact at the end of the seventeenth century there were only two, one in Amsterdam and one in The Hague. However, thanks to the unsparing efforts of the playwright and actor Jacob van Rijndorp (1663–1720), two more theaters opened: a second in The Hague in 1703 and one in Leiden in 1705. To expand and modernize the theatrical repertoire, Van Rijndorp wrote six serious plays, several commemorative pieces, and more than ten farces, only one of which, The Marriage of Cloris and Rosie (De Bruiloft van Kloris en Roosje, 1727), is still remembered today. His three daughters grew up to be celebrated actresses.

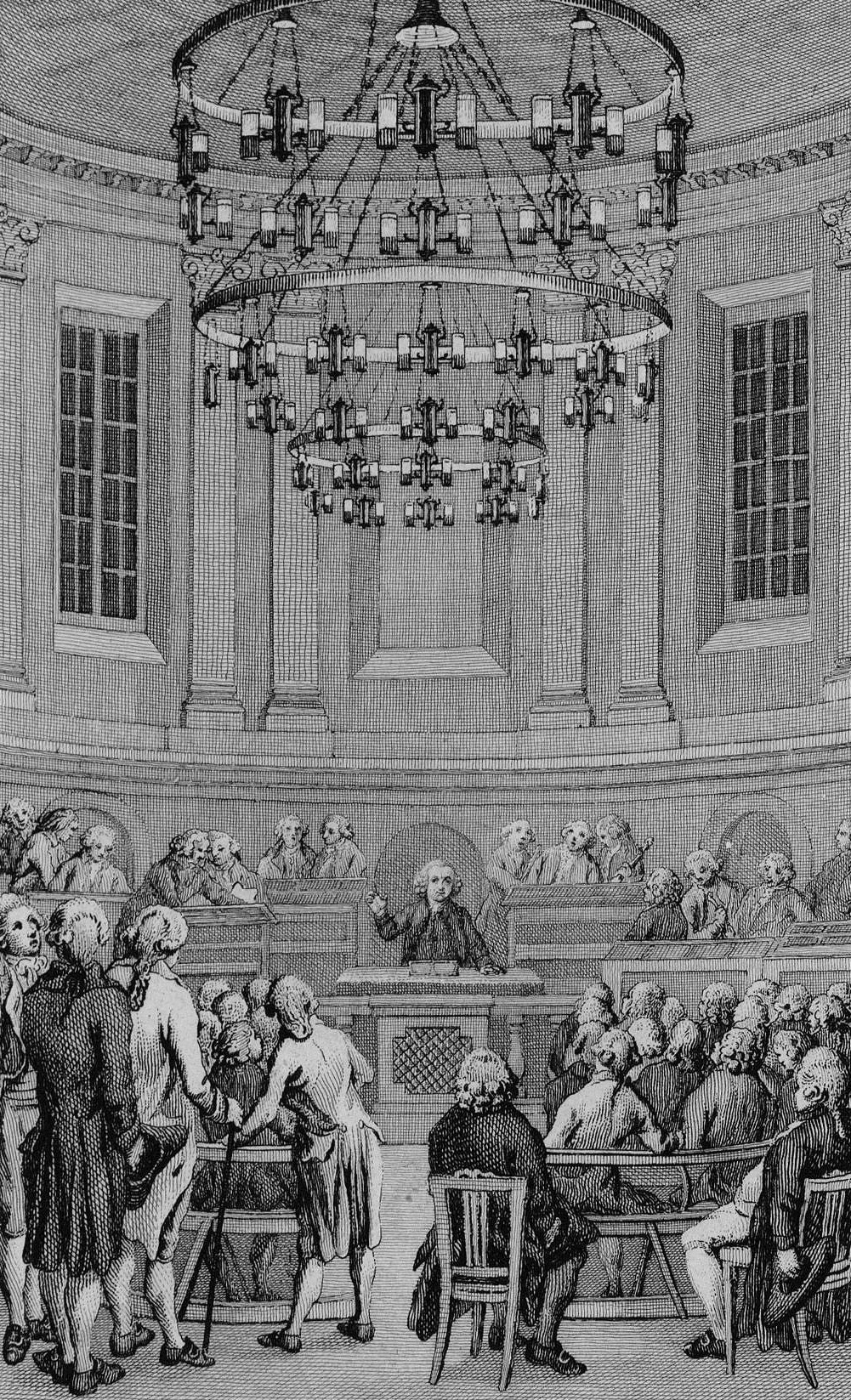

Further municipal theaters were established in the course of the eighteenth century. Rotterdam acquired a permanent playhouse in 1773, and Utrecht finally followed in 1796. None of these enjoyed as much prestige as the oldest municipal theatre in the land, the Amsterdam Schouwburg. The author of any play performed there had reason to be pleased, even though his only fee was a year’s worth of complimentary tickets. Productions at the Amsterdam Schouwburg were governed by strict rules, according to the dictates of French classicism. Religious and political plays were explicitly banned, partly to avoid conflict. Performances generally took place on Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, beginning at four in the afternoon. Audiences would be treated to two plays: first a tragedy or a comedy, then a comedy or a farce. There were no performances on Sundays or Christian holidays, and in times of war the theater was closed down altogether.

North and South had quite different repertoires. While the South favored religious subjects, in the Protestant North the performance of religious plays was forbidden. Church councils put pressure on the members of governing bodies of municipal theaters; to the clergy, the theater was pernicious by definition and they would have liked to see it outlawed altogether. Another factor was the influence of French classicism, which remained significant until at least 1730, especially in Amsterdam. French classicism banned religious and political subjects from theaters. Plays could feature national heroes only after they had been dead for at least two hundred years, and even then the material was sensitive. This probably explains the crisis in Dutch theater between 1730 and 1760, when hardly any new plays were written. Add to this the fact that Dutch actors, according to the Dutch Spectator in 1733, were in the habit of standing on stage yelling and gesticulating like lunatics, and the malaise of these years becomes tangible.

One of the few original minds and by far the most famous playwright of the first half of the century was Pieter Langendijk (1683–1756). He made his debut in 1711 with the comedy Don Quixote at Kamacho’s Wedding (Don Quichot op de bruiloft van Kamacho), which presents archetypal Dutch characters and chastises them for their foibles: a stupid farmer, a country yokel of a poet, a foreigner speaking incomprehensible Dutch. Langendijk targets his venom not only at declaiming peasants but at the whole genre of wedding verse, in which bride and bridegroom would be addressed in flattering but meaningless clichés. His peasant poet Jochem, however, takes a quite different approach. His poem to mark the marriage of Kamacho is not inspired by the lives of those involved but driven by the demands of the rhyme and by the poet’s own imagination:

JOCHEM sings:

And then he gave to her a ring,

And quoth, “My soul, who comfort bring,

I love her true, my clarty-fowl,43

My life in troth, my ape, my owl.”

CAMACHO: My ape? My owl? I nivver wooed her wi’ such stuff.

JOCHEM: It rhymes, though, perfectly.

CAMACHO: By t’ deuce, thou’st rhymed enough!

JOCHEM sings:

And then the maid spake up uncowed,

Her shift it draggled while she bowed,

And said, “My husband you will be,

For you can woo so prettily.”

CAMACHO: Her shift it draggled? But she didn’t even bow.

JOCHEM: It rhymes, though, perfectly.

CAMACHO: It rhymes like a drunken sow.44

JOCHEM sings:

“Why, thanks”, quoth he, “Young maid so sweet,

There’s one more wish which I entreat,

You know what I will say, and more,

My dillydown, my dove, my whore.”

CAMACHO: My whore? How dar’st thou, driveller? Explain —

and quick!

JOCHEM: It rhymes, though, perfectly.

CAMACHO: I’ll crack thy nob wi’ my stick!

This and other plays by Langendijk — The Mutual Marriage Deceit (Het wederzijds huwelijksbedrog, 1714), The Mathemartists, or the Young Lady Who Fled (De Wiskunstenaars, of ’t gevluchte Juffertje, 1715), and Mirror of Dutch Merchants (Spiegel der vaderlandschen Kooplieden, 1760) — could be described as comedies of manners. They criticize contemporary Dutch mores, largely for entertainment purposes. Cornelis Troost (1697–1750), an actor and famous eighteenth-century painter, immortalized several scenes from Langendijk’s plays.

The year 1760 marked the start of a theatrical revival and the appearance of alternatives to the classical tragedy. Marten Corver (1727–94), director of the Rotterdam Schouwburg and an extremely popular actor, tried to reform the theater by introducing a more naturalistic style. The most important innovation was the updating of traditional (classical) tragedy, a trend that took its lead from Voltaire, who advocated combining the lofty decorousness of French classical theater, exemplified by Corneille, with the lively plotting of Shakespeare. One of the authors who helped to create an audience for this kind of theater was Jan Nomsz (1738–1803), known as the Dutch Voltaire. He wrote fifty-three works for the stage, making him one of the most prolific writers of the second half of the eighteenth century.

Other modernizing tendencies in the theater were for poetry to give way to prose and for ordinary citizens to replace aristocratic characters. The most important criterion here was truth. People wanted to be shown a recognizable world with everyday problems. It was a style that slowly gained ground, first in comedy, which had a less exalted status than tragedy, and later in tragic drama as well. One of its foremost proponents, Cornelius van Engelen (1726–93), hoped to influence the theatrical climate by publishing a Spectatorial Theater (Spectatoriaale Schouwburg), a series of translated prose works for the stage. Another theatrical trend, supported most prominently by Willem Bilderdijk, advocated a return to the origins of theater: classical tragedy.

III. Classical Poetry and Modern Prose, 1725–1760

The Peak and Decline of the Epic

The genre in which classical rules survived longest was the heroic poem, or epic. This is hardly surprising, since in the classical hierarchy the epic was the most exalted and prestigious literary form and therefore the most tightly regulated. Only highly talented poets tried their hands at it, and they were few in number even in the eighteenth century, when more poets were writing epics than ever before, as the genre allowed the detailed exploration of the Enlightenment ideals of patriotism and religious faith. In qualitative terms the epic reached a peak in the years prior to 1780, and Vondel’s John the Baptist (Joannes de Boetgezant, 1662), the first Dutch biblical epic, set the tone. The biblical epic was particularly popular in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, although the influence of French classicism, which forbade the portrayal of miraculous events or “merveilleux,” limited its readability considerably. Since poets in the Calvinist Dutch Republic were not expected to make the Bible more palatable by adding anecdotes of their own invention, most epics were essentially little more than glorified biographies.

Not until Abraham the Patriarch (Abraham de aartsvader, 1728) by Arnold Hoogvliet (1687–1763) would the biblical epic return in all its splendor. The work was immediately recognized as a masterpiece and was in its eleventh printing by 1792. Like Vondel and Poot, Hoogvliet was a self-made poet. He began work at the age of twelve in a public notary’s office, later taking a job at a moneylender’s in Dordrecht. After friends introduced him to poetry, he translated Ovid’s Fasti as a way of improving his Latin. When his dying father begged him to choose a biblical theme, he began work on a life of Abraham. The task so exhausted him that he was forced to rest for a period during the early stages of writing the tenth volume. The final result was praised as “a perfect Epic,” partly because Hoogvliet had the courage to exploit his poetic license to the full and refused to yield to the rules of French classicism: “I did not wish to bend the truth to fit foreign laws . . . / but have preserved it in its natural state.”

Miracles, forbidden by Boileau, return in full glory with Hoogvliet, who was also happy to pepper biblical accounts with details of his own invention. In volume 9 Abraham is seen personally educating his son Isaac, although there is no biblical evidence that he did so. More audaciously, in volume 2 Hoogvliet depicts the council of heaven as a gathering of all God’s qualities personified. Hoogvliet armed himself against potential critics in his preface, but there was no lack of criticism. One critic qualified his praise with the consideration that the work “conflicts with the truth of our religion and is altogether too bold.” He was also displeased with Hoogvliet’s account of the introduction of circumcision, which he thought “low and disgusting and, no matter how elevated by the command of our God, no subject for Poetry.”

Title page of Abraham the Patriarch (Abraham de Aartsvader, 1728). Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Another highlight of Dutch epic literature was the publication in 1733 of Telemachus by the poet Sybrand Feitama (1694–1758). It was a verse translation of François Fénelon’s secular prose epic Télémaque (1699), and this, many contemporaries felt, brought the Dutch Telemachus closer to perfection than the French Télémaque. The first secular epic to be written in Dutch was by the Frisian nobleman Willem van Haren (1710–68). The Adventures of Friso (Gevallen van Friso, 1741) is a fictional account of the origins and history of his home province of Friesland, describing how the heroic Frisian people liberated themselves from Roman rule. Friso is born in India, the son of a king. His many adventures eventually bring him to the North Sea and some time later he settles down beside one of the branches of the Rhine delta, where he establishes Friesland. One feature betrays Enlightenment thinking: a brother of Friso’s father imparts to him the secrets of Persian monotheism, which allows Van Haren to describe Friso in pre-Christian times as professing a faith strongly resembling the modern, rational Christianity of his day.

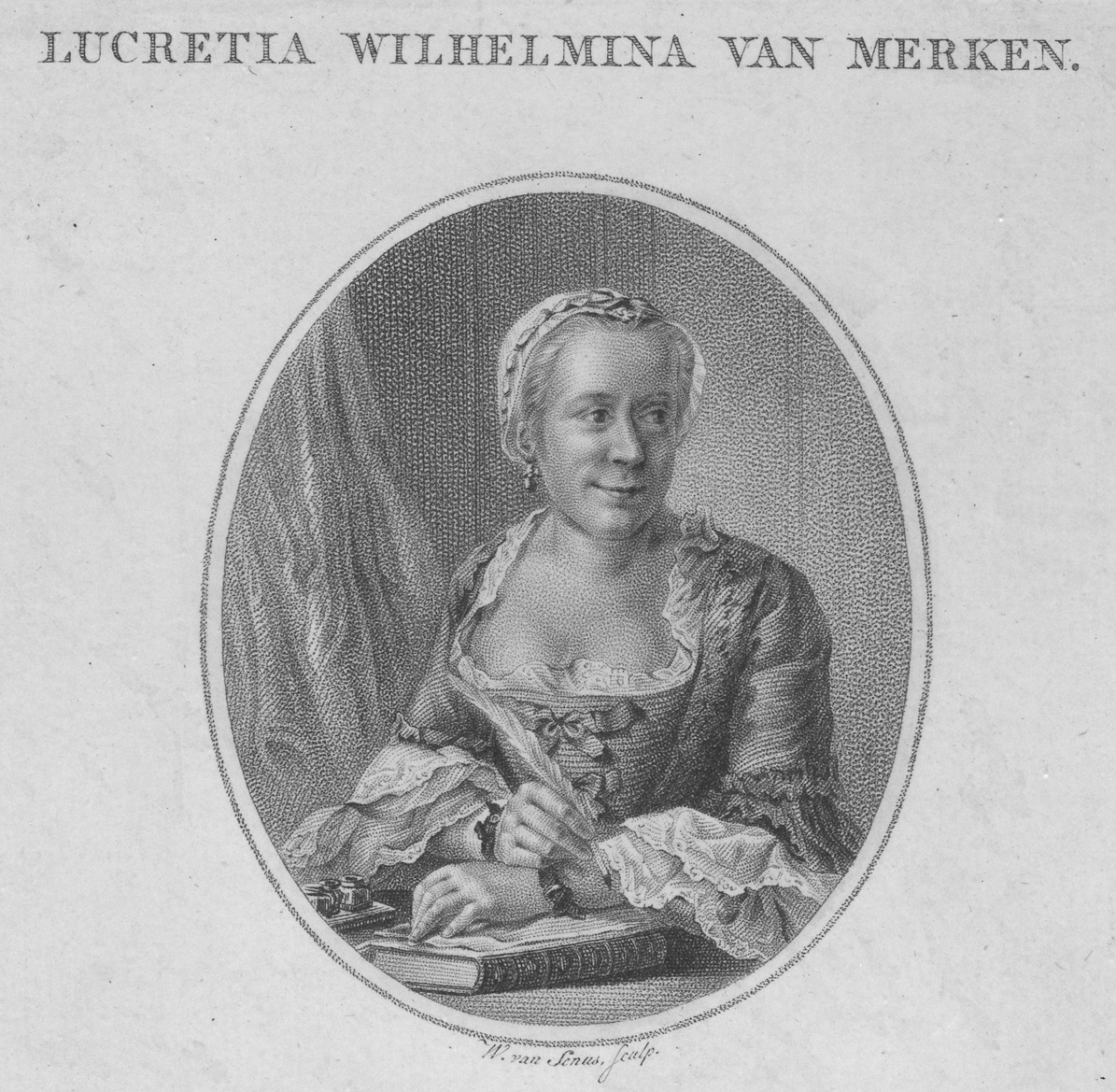

Another masterpiece of the genre was David (1767), by the most famous woman poet of the century, Lucretia Wilhelmina van Merken (1721–89), a biblical epic telling how the shepherd boy David, secretly anointed king by the prophet Samuel, eventually succeeds King Saul to the throne despite Saul’s jealousy and opposition. Van Merken chose this particular story to demonstrate that unlimited faith in divine providence would be rewarded. Not everyone was happy with her choice of hero. Willem Ockers, a critical freethinker, responded with a satirical poem called “The True Hero” (1768), which throws a very different light on David’s reputation by presenting him as a bloodthirsty murderer, guilty of crimes against humanity. After all, David had expanded his empire at the cost of many human lives.

After 1780 the epic gradually disappeared from Dutch literature. Classicism, its value eroded over the decades, was of little use to modern authors. Journals, epistolary novels, and plays written in prose gave writers more freedom to propagate their ideas and ideals. Besides, from 1780 both literature and society began to be markedly politicized and, since there was no place for politics within the system known as French classicism, the decline of the classical epic seems inevitable.

Colonial Literature

Colonial literature was a product of the northern Netherlands alone. The southern Netherlands had no colonies, and its trade with the East and West Indies was sporadic, whereas the Republic had developed a worldwide commercial empire, the main source of its prosperity, by the seventeenth century. Two large trading companies ruled the seas: the United East Indies Company or VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), founded in 1602, which traded everywhere from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to the small island of Deshima in Japan, and the West India Company (WIC; Westindische Compagnie), established in 1621 for trade in West Africa and the Americas. Pepper, spices, indigo, saltpeter, porcelain, silk, copper, and opium were imported from the East, while sugar, coffee, and tobacco came from the West. The route to the West Indies took ships along the west coast of Africa, where slaves were purchased for onward sale to plantation owners in Surinam and Guyana.

Ever since the late sixteenth century, Dutch travelers to the East Indies had written detailed accounts of the republic’s successful struggle for hegemony in international waters. Their stories of spellbinding adventures, along with detailed descriptions of exotic places, guaranteed the success of a new genre, the travel story, informative for those who stayed at home and all the more so for seamen preparing to venture into the unknown. Many of these travelogues were based on ships’ logs and therefore little more than factual, day-to-day accounts of life on board, but it was not unusual for writers to incorporate fictional elements — shipwrecks, encounters with monsters — to spice up their stories. Most successful of all proved Bontekoe’s Memorable Description (Journael ofte gedenckwaerdige beschryvinghe) of 1646, which had gone through at least seventy printings by 1800.

Along with these travelers’ tales, hundreds of songs about the East Indies have come down to us. Their literary significance is minimal, but they are invaluable as source material. Like travel stories, they are primarily informative and steer clear of literary embellishment. Journeys to distant lands, signing up for the voyage, discharge when it was over — sailors sang about every aspect, to familiar tunes. Many songs were intended as propaganda, helping to persuade new sailors to sign up with the companies by holding out the gratifying prospect of money, trade goods, and exotic women. Nevertheless, the songs give an unvarnished impression of the hard life on board ship. A sailor would sign up for five years’ service in the East Indies, but since the outward and return voyages each took an average of nine months, he would actually be away for some seven years, all told. The diet on board was meager: ship’s biscuit and water. Most men who joined up as sailors for the VOC did so out of either necessity or despair; few were motivated by a spirit of adventure. It seems there may have been some cultural activity on board, since to pass time at sea the men told each other stories, sang songs, or even put on plays. However, little trace remains of this on-board oral culture.

Although the VOC and WIC were trading companies, their directors were not averse to colonization and warfare in support of their commercial interests and against those of their competitors, Spain, Portugal, and Britain. Along their supply routes in both West and East, trade settlements were established that accommodated some cultural and literary activities. Prior to about 1800 these remained incidental in character and very unstructured, partly because the mobility of VOC officials and their high mortality rate were not conducive to literary activity of a durable kind. Nevertheless, there were bookshops, theaters, and the odd library in both West and East. Paramaribo, the capital of Surinam, had a number of theatrical societies and, from 1775 onwards, its own municipal theater. From 1772 the colony also boasted a newspaper, the Weekly Wednesday Surinamese Courant (Weeklyksche Woendaagsche [sic] Surinaamse Courant).