Edward’s fear of encountering a gang of robbers began to melt away as the days passed without incident. Until, that is, the day when something extraordinary happened to him as he rode along an especially lonely section of the trail.

He suddenly found his way blocked by three gnarled men with guns at their hips.

“Get down offen that horse, boy,” one of them commanded. He was a coarse looking brute.

Edward slid off the horse. One of the man’s partners ordered Edward to hold Blackie’s reins. The bandits made him empty his pockets. He held out the bits of change he had, which amounted to less than two dollars.

Edward knew that wouldn’t satisfy the thieves. They’d want to loot the saddle bags strapped to Blackie, which contained the mail and other packages he was carrying. He decided he couldn’t let that happen and used the plan he’d come up with when he’d been worrying about what to do if he was ever held up.

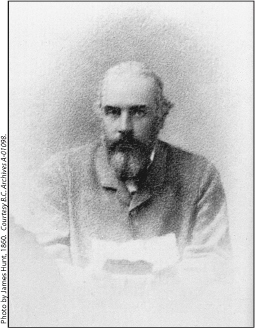

Judge Matthew Begbie imposed the death penalty so often he became known as “the Hanging Judge.”

Edward gave Blackie a good slap on the rump. Whump!

Off Blackie took, carrying the mail with him. The three highwaymen soon forgot about Edward. They leapt back on their horses and took off after Blackie. But as Edward would find out when he finally got back to Farwell, they never caught up to him. Blackie had casually found his way back to the stable, unconcerned about his romp in the forest. The saddlebags were untouched.

Edward reported the hold up to Constable Ruddick.

“Damn ruffians,” the policeman muttered. “Trying to rob the Royal Mail — that’s a hanging offence.”

That night, while wandering past the swinging doors of the Columbia Hotel saloon, Edward heard his name being called. It was Constable Ruddick.

“Come in here. There’s somebody who wants to meet you.”

Before Edward knew it, he was looking up into the face of Judge Matthew Begbie who happened to be in Farwell, having taken a break from his duties in Victoria as chief of the British Columbia Supreme Court.

“They tell me you’re a brave young man,” Judge Begbie said to Edward. “If those ruffians who held you up had gotten away with the mail, we’d have put the Mounties, as well as the Provincials onto them. And I bet they’d have got them, too. I’ve not the slightest doubt. Three more I would have had to hang.”

Judge Begbie congratulated Edward on his quick thinking in sending his horse off before the bandits could get the mail.

“A smart young fellow like you is going to make out all right in this country.”

Judge Begbie made Edward feel proud. But he frightened him, too. A man with so much power, a man who could put an end to a person’s life for just about any reason, was a man to stay away from. As soon as he could politely make his departure from the judge’s presence, Edward did so.

Ambling down the street, Edward decided the time had come for him to have a look at one of the hostess houses. He still wasn’t exactly sure what went on there, but he thought that if they rented out rooms, he might get a better place than the tiny room he was living in at the Columbia Hotel.

At one of the houses, he saw a red-headed woman standing at the door. She must be Irish Nell, he thought. He’d heard she was tough as nails, but that she had a heart of gold.

“Good evening, young man,” Irish Nell greeted him. “Would you like to come in and look around?”

Why not, Edward thought. He followed her into a front room that was set out as a parlour.

There were easy chairs, a sofa, and gas lamps. A painting of a woman wearing very few clothes hung from one wall.

“Do you have rooms here?” Edward asked.

“Something better,” Irish Nell told him. “Follow me.”

In the next room, Edward saw two of the girls that he’d noticed on the street earlier that day. He saw that both had their faces painted and were wearing what looked like the corset that he knew his mother put on when she wanted to get all dressed up — except these girls weren’t wearing anything over their corsets.

Suddenly, Edward realized he’d been a fool. This was no rooming house: it was one of those places where men went to meet girls.

“Uhh, I don’t think so,” Edward muttered, his face reddening. He turned and fled.

As he rushed out through the front parlour, Edward noticed three men had come in and sat down while he’d been in the back room. It was the three who had held him up in Eagle Pass!

Edward hurried down the street to the North-West Mounted Police post. He was glad to see Constable Ruddick there.

“I just saw them! The three who held me up. They’re over at Irish Nell’s.”

Constable Ruddick told Edward to stay where he was. Five minutes later, gun in hand, he returned with the three men in tow. They were a sad sight. Gone was the bravado they’d shown when they’d held him up. They filed meekly into the only cell in the small building.

The “Hanging Judge” — or Was He?

Matthew Baillie Begbie was born on a ship but became famous in the gold fields of British Columbia for his stern administration of justice, which earned him the nickname, “the Hanging Judge.” But he may have been unfairly tagged: the death penalty was mandatory for murder in his day and, in several cases, he successful argued for clemency and got many killers off with life in jail.

Begbie’s parents were aboard a British ship off the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, when Matthew was born. Educated in England, he was sent to British Columbia in 1858 to be judge in the new colony. He arrived just as the great Cariboo Gold Rush brought thousands of miners to the British Columbia interior. Lawbreakers were intimidated by his reputation and his appearance. He was an imposing man at six feet five inches tall, with white hair and a black mustache, and carried himself with an air of authority.

When Native people in the Chilcotin District killed twenty-one White men who had devastated tribal communities while building a road, Begbie had five of them hanged. During his years as a judge he hanged a total of twenty-seven men for a range of crimes.

Begbie made his views clear when a man charged with murder was let off with manslaughter: “Had the jury performed their duty, I might now have the painful satisfaction of condemning you to death, and you, gentlemen of the jury, you are a pack of Dallas horse thieves.”

Begbie became chief justice of British Columbia when the new province joined Canada in 1871. He once jailed an editor who criticized him. The editor, John Robson of the New Westminster paper, the British Columbian, later became the premier of British Columbia. Begbie also wrote many of the laws for the new province.

Begbie spent a great deal of time in the interior of the province. He once walked from New Westminster to Lillooet and back, a distance of 563 kilometres, and in one year alone he rode more than 5,000 kilometres.

Despite his fearsome reputation, Begbie championed a lot of progressive legislation. He was highly critical of laws discriminating against Chinese people. He called such laws “an infringement of personal liberty and the equality of all men before the law.”

Matthew Begbie was knighted in 1875 and died in 1894. Today, the historic Cariboo district gold mining town of Barkerville, British Columbia honours Judge Begbie’s life by staging annual reenactments of his famous trials.

“You go along, Edward, and we’ll let you know when we need you.”

During the next week Edward made two trips to Eagle Landing, which were both agreeable and profitable trips. He witnessed a number of accidents, many fights, and all sorts of thrills every day — all of which kept the doctors very busy. He happened on an emergency case once, when he found a doctor tending to a worker whose leg had been crushed by a load of rails. Another time, he saw two Chinese men fall from a cliff while they were trying to plant dynamite. Their boss, a White man, ordered them to get up and go to their tents. But Edward couldn’t stop thinking about how he would have to testify in court when the robbers came up before Judge Begbie.

Judge Begbie, even though he was now head of the British Columbia Supreme Court, still liked to “ride the circuit” as he had done for years, visiting out of the way mining and railway camps to dispense his brand of rough and ready justice.

Edward found a note waiting for him when he got back to his room one night, telling him to be in court the next morning at nine o’clock. The lobby of the Columbia Hotel served as a courtroom whenever it was needed.

A crowd had already gathered when Edward came down the stairs. Judge Begbie sat behind a large table with Constable Ruddick at his side. The three prisoners waited against the wall, guarded by a man carrying a shotgun.

Edward found himself sworn is as the only witness to the men’s crime.

“Can you point out the men who robbed you?” asked Constable Ruddick, whose job it was to question Edward.

“Yes. They’re right there.” Edward pointed to the men lined up against the wall.

“How much did the men steal from you?”

“I think it was about two dollars. They took all my change.”

Edward went on to explain how he had slapped Blackie on the rear and the bandits had ridden off after the horse.

“How do you plead?” Judge Begbie demanded of the men.

“Not guilty,” they all replied.

“Nonsense!” the judge bellowed. “You’re as guilty as sin. Robbing the Royal Mail is a capital offence and you’re all going to hang.”

“Oh, Judge Begbie, please don’t hang them,” Edward pleaded. “They only stole my change. They didn’t touch the mail. I don’t want them to hang on my account.”

Judge Begbie looked startled. He stared at Edward, glanced at the prisoners, and beckoned to Constable Ruddick. They whispered quietly to each other. Judge Begbie cleared his throat, and spoke directly to Edward.

“Edward, you must understand I am obliged to enforce the law. I only hang when hanging is warranted. But … maybe you’re right. Maybe they didn’t know you were carrying the Royal Mail. So I am going to grant your wish.”

Turning to the men, Judge Begbie passed sentence.

“Five years in jail. And if you ever come before me again, it’ll be the rope for all of you.”

Edward let out a deep breath. He might even have been more relieved than the three men who had just escaped the noose.