The second most exciting thing that happened to Edward while he was in Farwell — the most exciting being the time he was robbed, of course — was when the governor general, Lord Lansdowne, came to visit. He had been in Canada for two years as the personal representative of Queen Victoria. By all accounts, Lord Lansdowne had taken a great interest in the building of the railway to the Pacific. He was known to be a good horseman with a passion for fishing and all things outdoors. The governor general and his wife got off the train at the end of the track east of Farwell. That night, Lord Lansdowne penned a letter to his mother:

We travelled from the summit of the Rockies (in railway parlance the point where the railway begins to go downhill) to the end of the track.

Breakfasted in the car at 7:20 and took ponies to resume the journey, rode about 18 miles over fearful ground, but thro’ the grandest possible scenery to a railway village called Farwell where we camped very comfortably in tents provided by the Ry. People.

Edward was there for Lord Lansdowne’s visit to Farwell in 1885.

Edward followed along with the governor general’s party the next day. He stayed just far enough back so as not to be questioned about what he was doing.

At about eight o’clock the regal visitors rode out of Farwell, bound for a First Nations reservation. They were met by a Native man, known as Red Crow, and his principal chiefs, all of whom were on horseback and wearing their finest leather coats topped by feather headdresses.

Lord Lansdowne was escorted to a chair where, surrounded by his staff and the North-West Mounted Police, he sat to receive Red Crow. Red Crow and his chiefs sat on the ground, in a semi-circle, while an interpreter put their words into English. It was mostly complaints about how the government was treating them. After a time, gifts were produced on both sides: a pair of field glasses were handed to Red Crow and pipes, knives, and tobacco were given out to the others.

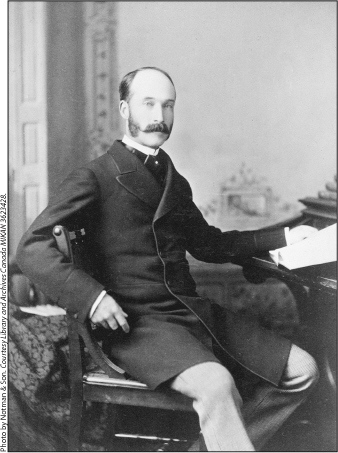

The Lord Who Loved Canada

Lord Lansdowne was governor general from 1883 to 1888, when the British Empire was at its glory and Queen Victoria’s new Dominion of Canada faced many challenges.

Born to an important family, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice came to Canada at a time when public confidence had been shaken by the Pacific Scandal over the building of the railway, and the country was in a recession. Then along came the North-West Rebellion.

As he travelled about Canada, Lord Lansdowne developed a great fondness for the outdoors, became an avid salmon fisherman, and took part in winter sports. His journey to Farwell (now Revelstoke) in 1885 gave him the opportunity to meet First Nations chiefs and visit outlying points by horseback and boat. He returned to British Columbia after the completion of the railway to travel all the way to Port Moody, which was the end of the line at the time.

Lord Lansdowne inherited a vast estate and was a man of great wealth. He served the British government in many capacities: he was the viceroy of India, then considered the jewel of the British Empire, and returned home to serve as secretary of state for war, and later as Foreign Secretary. He died in 1927 and left an estate worth over one million pounds Sterling (CDN$5 million; today worth about $60 million).

The governor general, Lord Lansdowne, met with the First Nations chiefs of the Shuswap and other tribes in the area when he visited British Columbia.

After the ceremony everyone stood while a bugler sounded “God Save the Queen” and people sang along to the Royal anthem. Edward’s chest filled with pride: he’d been brought up to admire Queen Victoria. As a good British boy, he was proud of his connection with the great Empire and the fact that he lived in a place named after his queen.

Then something happened that Edward could never have expected.

Colonel Sam Steele was in charge of the escorts who cleared the way for Lord Lansdowne. When he saw Edward, he pulled up his horse, ordered the procession to halt, and turned to the governor general.

“Your Excellency, I want you to meet a fine young man. Typical of the kind of brave young boys we’re bringing up in this country.”

Edward was stunned. He didn’t think Colonel Steele knew about him. He could only stand and stare as the governor general trotted his horse his way.

“This is the boy who carries the Royal Mail over Eagle Pass. He was held up the other day, but had the presence of mind to send off his mount before they could get at the saddlebags. We caught the ruffians, and they’re in the penitentiary by now.”

“I see they start them young in Canada,” the governor general said. “You’ve done well, young man. Keep that up and you’ll have a bright future. I could use somebody like you in the Horse Guards. Always need good men at my place in Wiltshire, Bowood House.”

Bowood House was one of the most stately homes in England, situated amid a two-thousand acre estate, but Edward couldn’t have known this.

After Lord Lansdowne’s brief word, he spurred on his horse, and the official party rode on.

Edward travelled back to Farwell that night, happy that he would have an exciting tale to tell about his encounter with the governor general in a mountain valley beyond Farwell.

But the governor general wasn’t the only remarkable person Edward met during his remaining days in Farwell.

Edward liked to watch the men building the railway. He would stare transfixed, as fifty or sixty men hung on ropes above Summit Lake while they drilled holes in the rock face of the mountain. Their job was to fill the holes with dynamite sticks that had been laced together with a long fuse, which was lit twice a day by the man charged with setting off explosions. When it went off, a tremendous blast would shake Eagle Pass. Hundreds of tons of rock hurtled through the air, coming to rest along the shore of Summit Lake. Sometimes the rock tumbled right into the lake.

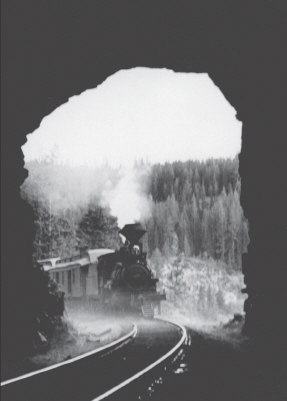

Building tunnels through solid rock was always a challenge for the railway builders.

After each blast, swarms of men with shovels and carts moved the loose earth and rock: they were all Chinese and looked like ants, slaving away for the good of the railway.

Edward was riding Blackie the day he met Dukesang Wong, and was anxious to get through before a storm struck. But the blasting held him up, and he noticed that one of the Chinese workers seemed to be giving directions to the work gang. When Edward heard the man speaking in English to the foreman, he decided to ride over and listen to what was being said.

“Gold Mountain is not as kind to us as we expected. Why can White men go unpunished, when we are punished for no reason and forced to work in the cold, with little food or clothing?”

Edward didn’t understand what they were arguing about. When the foreman rode off, he asked the Chinese man where he learned to speak English.

“My teaching master spoke excellent English, and he passed on to me, his poor, stupid student, whatever my small brain could absorb.”

Edward decided to choose his words very carefully, since he’d heard that the Chinese were very modest.

“My name is Edward. My poor horse and I ride twice this way every week.”

The man’s face lit up at Edward’s attempt to match the humility and reticence that were distinguishing characteristics of cultivated Chinese conversation.

“I am called Dukesang Wong. I have worked with the railway all the way from New Westminster. It has been hard and terrible work that my countrymen have been given. We will be happy to see the end of the building of this railway.”

Edward told Dukesang that he had watched the Chinese workers and thought they were very brave, and eagerly accepted Dukesang’s invitation to share a meal.

As Edward followed Dukesang into his tent, he thought back to the days when he ran from Chinese in the back streets of Victoria. I know better now, he thought.

“Here, here, sit,” Dukesang pointed to a folding chair inside the tent. There were two other men in the tent, who got up and quickly went outside. Dukesang called after them in Cantonese, and one of them came back with a plate of food for Edward. It contained part of a baked fish, rice balls, and a baked bun. Edward ate with his fingers, since he didn’t know how to use the chopsticks Dukesang offered him and there was no sign of a knife or fork. Dukesang held his plate close to his face, and expertly used chopsticks to transfer his food to his mouth.

After eating, Dukesang poured cups of tea for himself and his guest. Feeling more relaxed, Edward asked what it was like working for the railroad. He wanted to know how long Dukesang had been in Canada, and what he planned to do when the railway was finished.

“I’ll tell you my story, if you’d like to hear it,” Dukesang said.

“Oh, yes, I do. Tell me everything.”