The days were beginning to cool and nightfall was coming on early, signalling the approach of autumn in the mountains. Edward felt the chill of a stiff breeze on his face. He buttoned up his jacket as he rode along the tote road from Farwell to Eagle Landing; he had only a few packages of mail and parcels crammed into his saddlebag. A strange stillness had settled over the forest. Construction camps and gambling halls, where the sounds of cursing and carousing had once filled the air, were now silent and abandoned.

Dukesang Wong and his countrymen were finished building the most difficult part of the rail line. They had pushed beyond Summit Lake and were approaching Eagle Pass. It wouldn’t be long before they’d meet up with the crews working their way from the East. Those gangs, mostly labourers from eastern Europe, had conquered Rogers Pass and were now almost in Farwell.

As he looked around on his last ride on that late October day, it seemed to Edward as if some scourge had swept through the mountains. Wayside houses were shut up and deserted. He saw dozens of men, laid off by the railway, trudging on foot with all their belongings, headed back to Eagle Landing. Their abandoned camps looked ghostlike at night. The sight gave Edward the shivers as he opened his bedroll and settled down to sleep under a large fir tree.

The thing that stood out the most on this last trip was the way the silence was broken only by the hideous shrieking of construction locomotive whistles as they hurried along, their flatcars loaded with steel rails. The rails fell with a dull clang as they were dropped onto ties, ready for the spikes that would hold them in place.

Edward felt overcome by feelings of sadness and loneliness. Where there had once been the laughter of the gamblers and the shouts of “Stand to!” and “Look out below!” as nitroglycerine blasts threw tonnes of rock through the air, all was quiet. Edward lay awake for a long time, thinking about everything he had seen and done. He decided it was time to pack things in. He’d made a few dollars and he would have no shortage of stories to tell when he got back to Victoria.

A few days later, Edward returned Blackie to the Farwell Stables. He felt like he was abandoning the best friend of his life. He wrapped one arm around the horse’s neck, patted him on the rump, and told him he would never forget him.

There was time for one last walkabout around Farwell. At the post office, he said goodbye to Mr. Gordon and thanked him for the chance he’d given him to carry the mail.

While he was there, the famous Albert S. Farwell wandered in. Mr. Gordon introduced him, but Mr. Farwell didn’t seem much interested in young Edward.

Edward knew that Mr. Farwell was fighting with the CPR over where the railway would build its station. He wanted it on his land, but the CPR had other ideas: it had all kinds of property of its own, farther up the hillside from the river. Mr. Farwell said he was going to sue the CPR. Mr. Gordon wished him luck, but warned him that the CPR usually got its way. None of this made much sense to Edward and he slipped quietly out the door while the two men continued to argue.

Walking along Front Street, Edward was amazed at how quickly the town was growing. There was a store selling wine and liquor, and another offering various kinds of jewellery. There were Chinese joss houses, where the railway labourers gathered to burn incense and pray to their gods and ancestors. And, of course, there were the hostess houses, quiet in mid-afternoon. Edward knew they’d be busy that night because it was payday in Farwell.

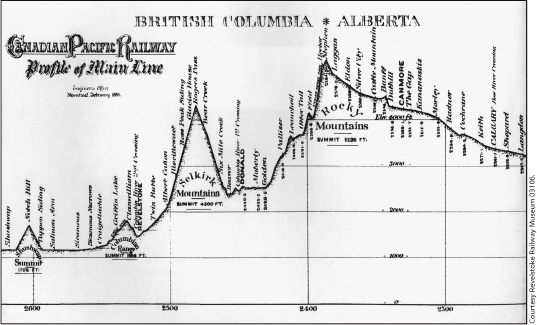

This CPR main line chart shows how the railway line scaled mountain heights and plunged into valleys as it made its way into British Columbia.

There was one thing that always lifted Edward’s spirits, and that was the beauty of the mountains around him. He was glad of that that afternoon, as he raised his eyes to the vast glacier that covered most of the great peak towering over the horizon. He was looking at one of Canada’s last great glaciers. Unknown to Edward or anyone else at the time, the climate was getting milder after many years of cold weather. In another century, the great glacier Edward was looking at would shrink to one-third its size.

There was one thing Edward was determined to do before he returned home to Victoria: see the completion of the railway. Constable Ruddick had told him there would a ceremonial driving of the Last Spike, and that it would take place in a few days at Craigellachie. Edward decided he would be there.

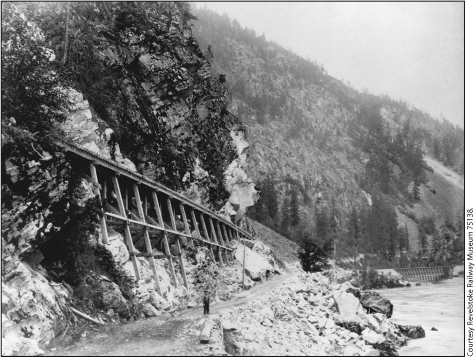

Trains crossed many trestles similar to this one in Eagle Pass near Craigellachie.

Edward’s spirits lifted again when he saw his old friend.

“Why Mr. Ferguson, I haven’t seen you since you got off the boat in Kamloops!”

“That’s right, lad, and here we meet up in Farwell.”

Edward had all kinds of questions for Mr. Ferguson. “Did you cut all the ties for the railway? How are things at your sawmill? Did you know they’re going to drive the Last Spike in a few days?”

Mr. Ferguson chuckled when he heard Edward’s questions.

“We delivered the last load of ties yesterday,” Mr. Ferguson said. “Dumped them off in Craigellachie. That’s where they’ll be driving the Last Spike. I’ve come along for the ceremony.”

Edward wondered why the place where the railway was coming together was called Craigellachie. He’d heard people in Farwell throwing around that name, but what was so special about it? There was nothing there but a collection of bunk houses and a pile of steel rails and equipment. He decided to ask Mr. Ferguson if he knew what the name meant.

“Famous place in Scotland, mentioned in a Scottish poem. It’s a favourite of George Stephen, the president of the CPR. He likes to quote it. Says the railway, like Craigellachie, will never be moved. Get on with it! Raise the money! Get the line built! Don’t be moved! Craigellachie!”

As Edward and Mr. Ferguson were talking, CPR locomotive No. 148 was chugging its way across the prairie, its diamond-shaped smokestack belching puffs of black smoke that vanished into a clear blue sky. It was pulling a cordwood tender, two fancy parlour cars named the Saskatchewan and the Matapedia, a dining car, and a caboose. Aboard were some of the highest officials of the CPR.

The train had set out nearly a week before, from Montreal, for its date with destiny. After years of struggle, political infighting, and financial high wire antics, the railway was only days from being finished.

“They’ll all be on that train,” Mr. Ferguson told Edward. “I imagine Mr. Smith — that’s Donald Smith — will be enjoying a nice bottle of Scotch. There’s a man who started out as a fur trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Worked his way up. One of the big investors in the railway.”

Mr. Ferguson asked Edward if he’d ever heard of Sandford Fleming.

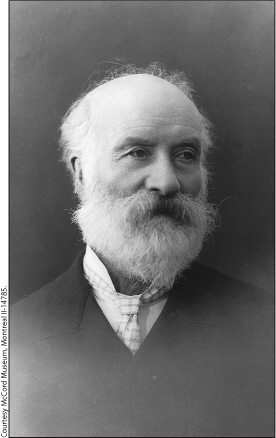

Sandford Fleming drew up the first plan for a railway across Canada. For a time he served as chief engineer of the CPR.

He Dreamt the “National Dream”

Sandford Fleming is known as the “father of Standard Time.” He is less well-known as the man who first dreamt the dream of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Even before Confederation, Canada was a country wild about building railways. It was the only way to span the vast distances of this great new land. Fleming had come to Canada from Scotland at the age of eighteen and took up work as a surveyor. He became the chief engineer of three different railways, one in Ontario, the Intercolonial from Montreal to Halifax, and the Canadian Pacific Railway.

In 1862, Fleming had set out a scheme for a “highway to the Pacific.” His estimate of the cost, one hundred million dollars, turned out to be right on the mark. Many thought it would be cheaper to go through the United States, but Sir John A. Macdonald felt otherwise.

Macdonald gave the contract to the Canada Pacific Railway Company, organized by Hugh Allan, a Montreal financier, in 1871. Macdonald was forced to resign when it came out that he had taken money from Allan to finance an election campaign in what became known as the Pacific Scandal. After returning to power in the 1879 election, Macdonald pushed ahead with the railway through a new syndicate formed by George Stephen. The first spike was driven at Bonfield, Ontario, a village near North Bay, in 1881.

When Sandford Fleming arrived in Craigellachie for the Last Spike, he was no longer chief engineer. He lost that job when a royal commission blamed him for delay and confusion in the railway’s construction. It didn’t bother Fleming, though: his idea for standard time around the world had caught on. No longer would every town set its clocks by its own reckoning. The world was divided into twenty-four time zones, with Greenwich, England, as the prime meridian.

“He’ll be on the train, too. First man to get the idea of building a railway from coast to coast. Invented standard time, so each little village isn’t running its clocks on its own time. A great man.”

About the only important person not on the train, Mr. Ferguson said, would be the president of the railway, George Stephen.

“Him and Smith are cousins. But Mr. Stephen’s off in England, raising money to finish the line.” His quest had been successful: the English banker Edward Baring, of Barings Bank, was advancing them the money.

Edward was one of the first to see the train, with a big number 148 on its front, steam into Farwell. He caught sight of the distinguished passengers as they alighted to walk about the town. Mr. Ferguson was right up there with them, showing them around. Of course, Edward didn’t dare speak to any of them.

The train sat on a siding for several days, waiting for the two work gangs to meet each other at Craigellachie. Steady rain turned the thin mountain soil into mud, holding up the last few miles of construction. Edward checked every day for news of the work. Finally, on Thursday, November 6, 1885, word came that the last supply train, consisting of an engine, a tender, and three flatcars loaded with steel rails, would leave that afternoon for Craigellachie. The fateful hook-up would take place the next morning.

Leaving his satchel at the Columbia Hotel, Edward hurried down to the tracks just in time to see the flatcars being shunted into place behind the engine. He saw several men clamber on board. He ran to catch up, and swung aboard the last flatcar just as the train began to pick up steam.

Huddled among the cold rails, he thought of his earlier ride from Golden when he also clung to a flatcar loaded with rails. It had been warm that day, but not today: he was facing a cold, cheerless, and rough ride. A few miles outside Farwell, it started to snow.

The snow made the tracks slippery and the train had difficulty making its way up the grade into Eagle Pass.

Three times it ground to a halt before sliding back. Finally, in desperation, the engineer ordered the last car to be cut loose. Edward hurried to jump aboard the second of the two remaining flatcars.

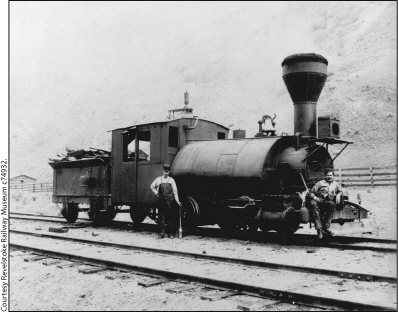

Edward’s flatcar was pulled through an overnight blizzard by a steam locomotive like this one.

Through a bitter night of driving snow, Edward shivered along with the other men who were riding the rails. He felt shaken almost to pieces as the little train made its way slowly over the rough roadbed. No one was able to sleep. The snow turned to sleet, and Edward was thoroughly soaked by the time the train pulled onto a siding at Craigellachie. It was pitch dark, and Edward was stiff and half-frozen; he couldn’t see where he was. It was all he could do to make out the shape of an empty boxcar on an adjoining track. He crawled inside and, exhausted, fell into a deep sleep.