The scent of the sea filled Edward’s nostrils. He’d forgotten the tangy smell of salt air during his time in the mountains. His summer had been filled with the aroma of pine needles and alpine flowers. On the nights when he huddled in his bedroll, thrown under a tree on the forest floor at some convenient resting place on his rides between Farwell and Eagle Landing, their fragrance had been like perfume.

Edward stepped from the back platform of the caboose onto the rough wooden deck of the Port Moody station as the work train squealed to a stop. It had reached the tip of Burrard Inlet, the end of the line for the Canadian Pacific Railway. From the station, Edward could see a few boats tied up at the dock. He thanked the conductor for letting him share the comfort of his caboose.

“The next time you want to travel, you’ll have to buy a ticket,” the conductor told Edward. “No more free rides once the passenger trains get rolling.”

Edward considered going down to the dock to see what was happening, but he decided against it. He needed to travel a few miles overland to New Westminster, where he could catch a steamer that would take him home to Victoria.

His satchel under his arm, Edward strode off down the rutted road that served as Port Moody’s main street. It had the usual collection of general stores, cafés, saloons, and ship provisioners. He asked the way to the stagecoach office, and was directed around a corner where he found a sign hanging over a false fronted building: pacific stagecoach.

“Stage’s leaving in five minutes,” he was told. “Fare’s a dollar and a half.”

Edward paid willingly. He had saved up two hundred dollars from his summer riding parcels and the Royal Mail through Eagle Pass. He felt rich.

The first thing Edward did when the stagecoach arrived in New Westminster was to go to the Royal George hotel where he’d stayed on his way upcountry. The desk clerk recognized him.

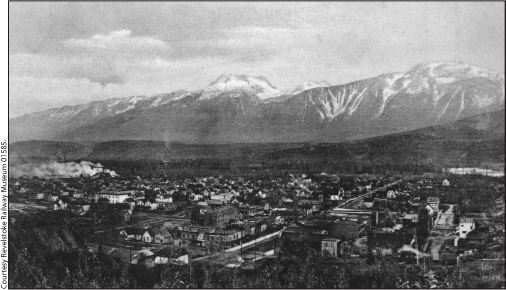

The city of Revelstoke filled the horizon, as seen from Mt. Revelstoke around 1900.

“I remember you. You look different. Not as pale as I remember. You’ve grown up.”

Edward was surprised by these remarks. He didn’t think he was any different than on that summer day four months ago when he’d first asked for a room. Later, looking in the mirror he realized that he had changed. He detected the first signs of a beard and his hair was shaggy, hanging down over his collar. Edward straightened his shoulders and stuck out his chest. I’m a man now, I know my way around. It occurred to him that the haircut he’d been given by a camp cook back at Eagle Landing hadn’t done much for him. He needed to improve his appearance; some new clothes might do it.

An hour later, Edward was back in his room with a bundle under his arm. There was a dry goods store across the street from the hotel, and he had bought new boots, a jacket, and a pair of strong, blue denim jeans brought up from San Francisco. The storekeeper told him they’d been made by some man named Levi Strauss. The whole lot cost him almost fifteen dollars.

I’ll have to watch my money, Edward thought. At this rate I’ll soon be broke.

Early the next morning, Edward waited at the docks on the Fraser River for the Rainbow to sail for Victoria. It got underway just after eight o’clock. He was excited at the thought of being home by evening. The time passed quickly. Edward struck up a conversation with a young man who was on his way to set up a law practice in Victoria. Edward amazed him with accounts of his experiences in the mountains. Afterward, he worried that he might have sounded boastful, but he couldn’t stop himself from talking about his adventures — especially getting his picture taken at the Last Spike.

It was dark when the boat docked in Victoria. The Mallandaine house on Simcoe Street was but a short walk from where the Rainbow had tied up. Along the way, Edward picked up the scent of the city. There was an acrid smell of smoke, from the burning of sawdust at a mill, and the sweet aroma of roses that were still blooming in several yards. The streets were dark, except for one intersection that was lit by gaslight. There might have been a moon, but it was cloudy. It didn’t matter to Edward; he was glad to be home.

The front door of his house opened quietly when Edward turned the knob. He stepped inside. He could make out the glow of a gas lamp in the parlour. “Hello?” he called out, “I’m home.”

For a moment, there was no response. Then he heard the squeak of floorboards as someone came into the hallway. It was his father.

“Edward, I thought that sounded like you! You’re back! Mother,” he shouted. “Come directly. Edward’s home.”

Edward’s father put one arm on his shoulder, shaking his hand vigorously. His mother was there in an instant. He fell into her arms.

“Let me look at you,” she said. “Come into the parlour where I can see you. My, how you’ve grown. Hasn’t he, Father? Where did you get those fine clothes?”

The joy of the reunion filled Edward with happiness.

“Where’s the rest of the family?” His brother Charles suddenly tumbled down the stairs, followed by Frederick and the two girls, Louisa and Harriet. Charles danced around them while the others fired questions at Edward. Their chatter went on long into the night.

Edward had gifts for everyone. The most prized went to Charles: a rock into which the outline of a small sea creature was impressed. The railway workers had called it a “stone fish.” It was a fossil Edward had picked up on the bank of the Columbia River. The fossil was evidence of the time when, eons ago, ocean waves lapped the shore of the continent and the great peaks of the Rockies had not yet been thrust up from the bottom of the sea.

Edward saved his greatest piece of news for the last, after he’d told his family all about meeting Judge Begbie and the governor general, and being robbed. Charles was nodding off when Edward finally told them about his presence at the driving of the Last Spike.

“I am in the picture,” he said proudly. “The whole world will see I was there!”

Edward’s first few days at home passed in a whirl. He was anxious to see his old school friends and tell them of what he’d been up to.

When Edward went to his friend Jimmy’s house, he expected a warm welcome. Instead, his buddy treated him with coolness. He decided to tell him about being in the Last Spike picture. Before he could say anything, Jimmy told Edward that he’d heard about how he had had his picture taken. Jimmy didn’t seem too pleased.

“Just because you’ve done all that,” he told Edward, “doesn’t make you any better than anybody else.”

“I don’t think I’m better than anyone,” Edward said. But in his heart of hearts, Edward believed he’d done something that other boys of his age wouldn’t have dared. Still, he didn’t like his friend’s resentment of his accomplishment, and no longer felt as brazenly sure of himself. Edward resolved not to boast about how he’d ridden the Royal Mail or had been present at the driving of the Last Spike any more. He kept the idea that someday, when the picture is published in school books, every kid in Canada will know about him to himself.

A week after Edward arrived home, the British Colonist reported the hanging of Louis Riel for treason. The paper said his execution, which took place in Regina, was cause for great indignation in Quebec. Bonfires were lit in the streets of Montreal and riots broke out in several places. There were other hangings, but none created the ill-feeling that arose between the French and English than the fate of the instigator of the North-West Rebellion.

Edward gave little thought to all this. He was more concerned about his father’s reminder of his promise to return to his architecture apprenticeship. His mother also chimed in, questioning him about his plans for the future. It seemed he wasn’t to be given any time to decide what to do.

“Why must I make up my mind right now?” Edward wondered aloud.

The excitement of Craigellachie had barely worn off and here he was, being forced to choose what to do next. Architecture didn’t sound so exciting anymore.

Edward’s father made up his mind for him: “You’ll come back to the office, or you can’t stay here.”

Edward thought about leaving home again, but decided that he needed more time to make up his mind. Going back to his father’s office would give him time to think things over, at least.

Edward resolved to learn all he could about architecture. His father’s assistant began to teach him the principles of design and set him to work at a drafting table, where he learned to sketch floor plans and indicate the locations of doors and windows. As the months went by, Edward became comfortable working at the table in the corner of his father’s office. He got to accompany his father to sites where new houses were being built. And before long he began to create some of his own architectural plans from scratch.

Edward’s mother was glad to have her son home, but she worried about what would become of him. She noticed that he was getting interested in girls. “We must take care to see he meets the proper type,” she told Edward Sr. Louisa Mallandaine still held to the sensibilities of the Victorian society in which she’d grown up in England. She believed that people must marry within their own class and respect those further up the social ladder.

“Don’t worry about Edward,” her husband told her. “He’ll make his own way. This is a new country, you know. That old stuff went on in England, but it doesn’t count for much here.”

Some of Louisa’s concerns must have rubbed off on Edward. At times, he felt desperate about his life and what might become of him. He wanted to know himself better. When he heard about the phrenologist on Fort Street, he decided he must visit her. He’d heard many people speak in favour of phrenology, even if they didn’t understand it. You could read a person’s character by the bumps on their heads; the shape of a person’s skull had something to do with what’s in their brain.

Mrs. Thornton, the phrenologist, was a heavy-set woman clad in a long black dress. She held a lorgnette — a pair of glasses fixed to a fancy handle — and told Edward that her fee to read his head was twenty-five cents. Edward handed over the coin and sat in a chair in front of her. She stood behind him, and Edward could feel her running her fingers over the top of his skull, probing for bumps and fissures.

The examination took only a few minutes. Mrs. Thornton retired to a back room, and when she emerged, she handed Edward a card on which she’d rated the qualities of his character. There was a scale of one to seven. Edward wasn’t surprised when he saw he’d been given a rating of seven for appetite. He was rated six for mirth and wit, and five and a half for sexual love. Edward didn’t know anything about sexual love, but he felt reassured that he’d done so well in that department. But when he saw that he’d gotten just a two for respect for others, he swore he would do better in the future.

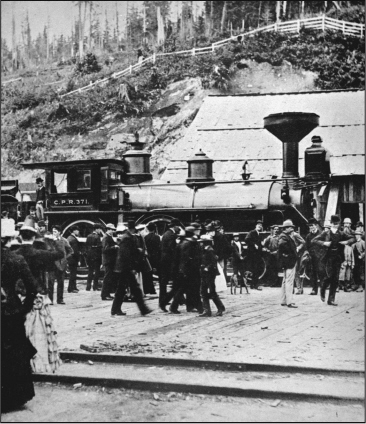

The first train to reach Port Moody. The railway had cut the travel time from Montreal from five weeks to five days and seventeen hours. The railway terminus was later moved to Vancouver.

At home, Edward noticed a difference in his father and mother. They seemed to be older and quieter than he had remembered them. Edward Sr. spent hours painting pictures of Victoria and scenes of the countryside; Louisa spent her time in her favourite rocking chair, sewing. His brothers and sisters, too, seemed to be more grown up. Charles didn’t want to roughhouse as much as he used to and Frederick started keeping to himself. His sisters … well, they were just girls.

Edward didn’t entirely realize it, but his life was unfolding before him. The rest of the world was changing, too. The first regular through train from Montreal reached Port Moody the summer after Edward arrived home, on July 4, 1886. It took just five days and nineteen hours. Before the railway, a journey across Canada took anywhere from eight to twelve weeks.

Edward was surprised, along with everybody else, when he heard that the CPR had decided to extend the railway to a place known as Granville, or Gastown, since some people called the village after Gassy Jack, a pioneer saloon keeper. Mr. Stephen thought it needed a more respectable name and decided to call it Vancouver in honour of Captain George Vancouver, the British naval officer who had first sailed around the island that would bear his name. Besides, the name was well known in England, and it would be good for business to name the city after such an illustrious figure. Not long after, the whole place burned to the ground. But just as had happened in Farwell, it was rebuilt faster and bigger than ever before.

By now, Edward was beginning to find life at home dull, even stifling. He longed for the freedom he’d enjoyed watching the railway construction and riding the Royal Mail.

He was a man now, and he knew he couldn’t rely on his father for a job forever. He decided that he must return to the mountains. It was there he would feel at home again.

Edward thought of the mountains of British Columbia as monuments to the dawn of history. He wasn’t sure what great force had brought them about, or when. He only knew that when the sun shone on their savage peaks, and cast dark shadows into their deep chasms, there was no sight like it. He’d seen black bears feast on berries in summer and fish salmon from the Eagle River in fall. He’d watched mule dear and mountain goats browse on the last greenery of the season. He had heard that mountain lions prowled the forests of lodgepole pine, though he had never seen any. He’d seen wild flowers bloom in gold and amethyst, preparing for their return to the thin soil come winter.

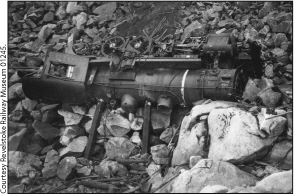

Trains were sometimes derailed by landslides and washouts, as shown in this photograph of the wreckage of a steam engine.

He also understood that the passage of the railway through the mountains had forever changed life on and around them. He’d been there when the sound of change was first heard; the mysterious whistle of escaping steam that signalled the presence of man. It had echoed against the peaks throughout the night and at dawn on November 7, 1885, when the train that he rode into Craigellachie squealed to a halt. He was there for the act of Canadian nation building that took place on that historic day. He knew now that one day he would have to return to the mountains. Their call was irresistible.

The Trains Still Run

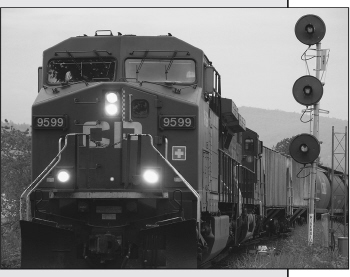

The Canadian Pacific Railway may have abandoned passenger service and has closed many of its lines, but its freight trains still run from Montreal to Vancouver and major American cities, such as Chicago and New York.

Today, many people want a new era of railway construction that would give Canadians high speed trains between such points as Windsor and Quebec City, and Calgary and Edmonton.

Canada today is a vastly different nation than the one that was bound together by the Last Spike. The Internet, cellphones, and iPods provide instant communication and entertainment. Canadians celebrate their multicultural diversity and respect the First Nations people. But the memory of that long ago occasion, when Edward Mallandaine watched Donald Smith swing the hammer that changed Canadian history, will never fade away. The click of the photographer’s shutter that stilled the morning’s mist has seen to that.