A cooling breeze brushed Edward’s face as he walked up the gangplank of the S.S. Rainbow just after eight o’clock one Sunday evening. The whole family had attended morning services at St. John’s Anglican Church. Edward’s father told the minister that he was leaving on the evening steamer for the North-West.

“I’ll say a special prayer for Edward’s safety,” Reverend Wilson told the family. “May God look after him.”

Edward turned for one more look at his family gathered on the dock below. They were waving to him. All had smiles except his mother, who wiped a tear with her handkerchief, then looked quickly away. The steamer would be leaving in a few minutes for New Westminster. For the hundredth time, Edward checked his ticket and saw again that he was assigned to cabin C-3. This meant he’d make the voyage across the Strait of Georgia on the ship’s lower deck.

Edward went straight to his cabin, stowed his satchel, and returned to the second deck to watch the departure from Victoria Harbour. As the Rainbow slid away from the dock Edward ran his eyes along the familiar rocky shoreline. At last I’m on my way, he thought. I’ll not be back for awhile. The prospect of adventure sent a tingle down his spine.

Edward knew that the Rainbow was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company, but he paid that fact little mind. The steamer was one of several built in England that were used to ferry supplies in and out of various towns and trading posts up and down the British Columbia coast. Plumes of grey and black smoke billowed from its single smokestack, evidence that the ship’s wood-burning furnace was now filled with blazing logs. Close to the prow of the Rainbow stood the pilot house, and behind the smokestack were the top deck cabins, reserved for first-class passengers. They would enjoy fine views through their portholes, even if the breeze wafted the occasional spark or bits of ash their way.

Once on open water, the Rainbow began to rock with the swell caused by the waters of the Pacific flowing into the narrow gaps of the Strait of Georgia, the span of water separating Vancouver Island from the Mainland. It was getting dark and Edward could just pick out the blurred shapes of the San Juan Islands off of starboard.

The islands were now American territory. Edward remembered what he’d learned in school about the Pig War. In 1859, an American settler on the islands had killed a Hudson’s Bay Company pig. Soon, American troops were facing off against British soldiers intent on arresting the farmer. It took the German Kaiser, Wilhelm I, to settle the dispute. He had awarded the islands to the United States.

Edward preferred to cast his eyes in the other direction, toward the Gulf Islands on his portside. No one challenged their belonging to Canada. He could just make out the Pender Islands, and beyond them, Saturna Island. He’d heard it had especially beautiful beaches.

As he stood at the ship’s rail, a man in a bowler hat approached him.

“Well, young man, where are you bound?” Edward told the man, who said his name was Duncan Ferguson, that he was going to enlist in the Canadian Militia, somewhere on the Prairies.

“Aye, m’lad, I think that fight’s about done,” Mr. Ferguson said.

He went on to tell Edward how a force of troops and North-West Mounted Police were battling the rebels. Mr. Ferguson spoke with such a thick Scottish brogue that Edward couldn’t understand all he was saying.

“In all my thirty years in this country I’ve never ken such confabulation.”

Edward said he was going anyway.

“You never know when the Indians might rise up and attack White settlers.”

The Rainbow was at full speed now, making between ten and twelve knots. That meant it would take nine or ten hours to complete the hundred kilometre journey to New Westminster. Edward thought he may as well go to bed; he wanted to be up early. His ticket included breakfast, and he looked forward to being awake when they entered the estuary of the Fraser River.

The next morning, with an appetite amplified by the bracing sea air, Edward was among the first to line up outside the dining room. Looking out, he could make out a long stretch of flat, empty land reaching back from the river, and beyond that, the sudden rise of mountains. There was a lumber mill and, next to it, a cannery where a lot of people were moving salmon onto long tables.

The dining room doors were flung open and Edward wasn’t ready for the rush of passengers. He felt himself being carried through the doors, and was pushed aside as men scrambled to take seats at the tables. Somebody knocked a Black waiter off his feet and the large platter of eggs he was carrying clattered to the floor. By the time Edward found a seat and waited for food to come his way, there was little left. He filled up on buns, toast, and coffee.

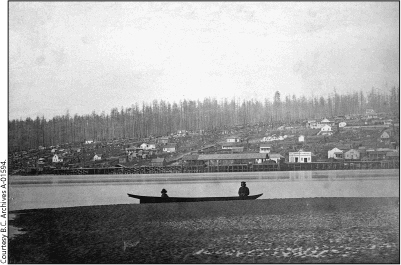

When the Rainbow docked in New Westminster, Edward saw that, since his last visit, the town had spread out further along the river’s north shore. About fifteen hundred people lived there, but it was still only about a quarter of the size of Victoria. A few three- and four-storey stone-and-brick buildings hugged the waterfront. Beyond them, on a hill sloping up toward the forest, wooden houses were scattered as though they’d been dropped by some strong wind that had blown through the place. On the other side of the river there was nothing but mud flats.

New Westminster in Edward’s day, viewed here in a photograph taken from the Fraser River, was a rowdy river town.

The usual commotion met the ship’s arrival. Dock workers started unloading cargo and passengers streamed off, one by one. After disembarking, Edward went straight to the Royal George hotel, where he and his father had once stayed. There was a new man at the front desk. At first, he didn’t want to give Edward a room.

Rascals and Rowdies in a Royal City

New Westminster was a rough and ready river port, filled with rascals and rowdies. Queen Victoria named it after the city of Westminster, which is the area of London where the parliament buildings for the United Kingdom are located. Because of this connection, New Westminster became known as the Royal City.

New Westminster is the oldest city in western Canada and was the first capital of British Columbia. It lost the capital to Victoria when the colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island were united in 1866.

Thousands of miners passed through New Westminster in the Gold Rush, and it became the main outfitting point for prospectors. Known to the Chinese as Saltwater City, it had a large Chinatown along Front Street, one of the city’s most important streets. As the land became more valuable, the Chinese were pushed out to an area known as “the Swamp.” Today, New Westminster is a prosperous and beautiful city of more than 60,000 people.

“What are you doing here alone, kid?” he demanded. Edward told him he was going by boat to Yale and then by train up the Fraser Canyon.

“In that case, you’ll be here two nights,” he told Edward. “The next boat’s on Wednesday.

That’ll be fifty cents a night.”

Edward dug a dollar in coins out of his change purse, signed the register, and went to his room. The window looked out over the river and he could see goods being loaded on a steamer tied up at the dock. It was the Adelaide, the little vessel that would take him up the Fraser River to Yale. That was as far as boats could go before reaching the impassable rapids in the Fraser Canyon: no boat could navigate such a treacherous stretch. Rails had been laid north of Yale, as far as Van Horne (also known as Savona), a small settlement named after William Van Horne, the general manager of the railway.

Edward spent the next morning wandering up and down New Westminster’s two streets of stores and warehouses. Bored, he bought bread and cheese and climbed the hill behind the town where he sat among the trees and looked down on the broad Fraser River. It was six-hundred metres wide and Edward could make out small fishing boats, which he guessed were trolling for salmon. Closer to shore, tugs pulled logs bound for the sawmill. On the other side of the river, flatlands stretched away to the south. He could see the peak of a large mountain in the distance. His father had told him that it was Mount Baker, and that it was just across the line in the United States.

Edward was up early on Wednesday morning, excited to be setting out on the next leg of his journey. The Adelaide had been designed specially to navigate the tricky waters of the Fraser and rode smoothly up the wide river.

Edward saw flocks of ducks and geese feeding in the shallow waters where the river had overflowed onto the surrounding flatland. That evening, the Adelaide docked at a small camp set amid steep mountains that ran right down to the water’s edge; they were a magnificent sight. Everything seemed to be narrowing at this spot, as if the river was being pushed into a crevice between the mountains.

The river was running faster than when Edward had been there with his father, and the Adelaide moved more slowly as it pushed against the downward current. It almost stalled a few times, and once it even spun around before the captain could order more fuel for the furnace. Then Edward heard three sharp blasts of the Adelaide’s whistle: the captain came out of the pilot house and told the passengers he could take them no further.

“The current’s running too strong,” he shouted across the deck. “We’ve had high water all this year, too much snow in the mountains. Still melting. I’ll have to let you all off at Emery Bar. Just around the bend. You’ve five miles to go to Yale. You’ll have to walk it, unless you take the stagecoach.”

There were twenty passengers on the boat and most grumbled as they disembarked. Edward noticed that Mr. Ferguson was among the passengers going ashore. It didn’t take long for Edward to realize that Emery Bar was nothing more than a stagecoach stop close to the opening of the Fraser Canyon. He saw Chinese workers hanging around the dock. A livery stable had a sign, carriages for rent. Some of the passengers headed for the stable, but Edward knew he’d have to walk. He put his cloth hat on his head, flung his satchel over his back, and set out on the narrow, rutted road that ran along the river bank.

As Edward walked along, Mr. Ferguson caught up to him, a little out of breath from having hurried to join him.

“It might be a good idea to stick together.” Edward didn’t mind, but he wondered if perhaps Mr. Ferguson was afraid of getting lost.

After they’d walked about a mile, following the path high above the Fraser River, the air grew hazy. It wasn’t long before Edward smelled something burning. Mr. Ferguson guessed that it must be a forest fire.

“It won’t bother us, we’re right on the river,” he told Edward. “Can always jump in if we have to.”

But the smell of burning grew stronger as they walked. Bits of ash rained down on their heads. Edward knocked a spark off his shoulder. Then, as they came around a sharp bend, he could see trees on both sides of the trail bursting into flame. The fire was burning its way toward them, as if it was thirsty and trying to reach the river.

“Keep yer head!” Mr. Ferguson shouted. “Follow me! Stay here and we’ll be burned up. Better be a coward than a corpse!”

He turned and started running back down the trail.

Edward wasn’t sure what to do. The fire seemed to be getting closer but he didn’t want to go all the way back to where they’d landed. There was nothing there. Up ahead lay Yale and a train to take him east.

Maybe I can jump into the river if I need to, Edward thought. I’m not turning back.

The forest was ablaze above him. The firestorm came in great sheets of flames and the sky filled with clouds of smoke. It had been a dry summer in the mountains, and the pine and spruce needles, filled with resin, burned and crackled like firecrackers. The noise of the fire was almost as terrifying as the heat of the flames.

Edward had heard that people who breathed forest fire air could die on the spot, their lungs burned to a crisp. He imagined himself as a bundle of burned bones on the forest floor and shuddered.

Before Edward knew it, his hat was on fire. He felt the heat on his head and smelled his hair burning. He slapped at his hat, threw it off, and ran his hands through his hair. Pieces of singed hair came loose from his scalp! Breaking into a run, Edward left the road and made his way down a steep bank to the river’s edge.

He was on the edge of a small clearing, out of the main fire zone. The clearing acted as a natural fire break, confining the blaze. Edward knelt at the river bank and dunked his head in the water. It stung where the cold water touched the burn on his scalp.

“You’re a lucky lad,” he heard a voice behind him. It was Mr. Ferguson.

“I’ve come back after ye,” he said. “Couldn’t leave ye here all alone. Ye didn’t see that tree fall almost on ye. It came down just behind ye. I had to jump over it to get clear. We could ‘ave been burned to a crisp!”